The various state VMT-fee pilots deploy a range of administrative schemes. While almost all involve their departments of transportation—Virginia’s program is the exception as it is housed under its Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV)—some include other state-level departments and stakeholders. For example, Utah’s program is operated out of their DOT, but their DMV shares data to support essential program functions, such as determination of vehicle type. Minnesota had included their department of revenue in its most recent iteration because they manage their existing fuel tax collection. For almost all of the state pilots and programs, the management of participant accounts is outsourced to a private-sector commercial account manager (CAM), such as Azuga or Emovis. Oregon offers in-house account management to its participants alongside both Azuga and Emovis and is the only program that currently does so.

State leaders saw this outsourcing as successful, because they could leverage technologies and workforce that already existed, remove themselves from data privacy concerns, and provide their participants with value added services that CAMs can offer, such as trip history and fuel usage.

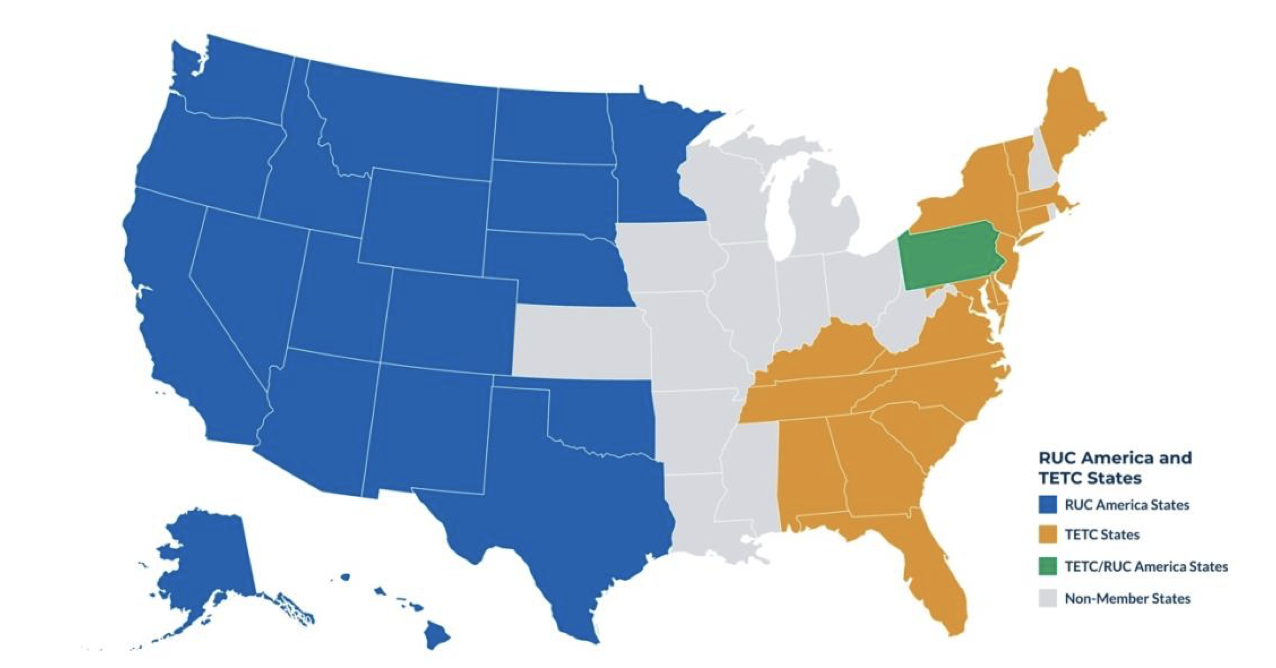

For commercial vehicle pilots, the administrative structure has looked similar. TETC’s Multi-state Truck Pilot (2018-19) and their National Truck Pilot ((2021-21) partnered with EROAD, a transportation technology solutions company based in New Zealand, to leverage the data already collected for their customers through their on-board units. [Note 4] TETC’s partnership with a CAM allowed for the offloading of data collection and data protection to a commercial entity with experience and expertise.

For the federal pilot, IIJA prescribes some of the administrative structure. IIJA stipulates that the U.S. Treasury Department should collect revenue as a part of the pilot, but where the program should be housed at USDOT is not prescribed. Additionally, since the federal government does not have a department of motor vehicles or a national vehicle registration system, the administration of a federal pilot will likely need to look different from that of the state pilots.

The administrative structure of a national pilot will also need to consider how to interface a federal program with an existing state program in an interoperable manner. As of July 2023, there has been no instance where a vehicle owner has been able to participate in two VMT-fee pilots or programs that have been administered by two separate entities.

New Zealand

A RUC has been implemented in New Zealand since 1977. [Note 5] The program only includes vehicles (both passenger and commercial) that use diesel fuel, and any vehicle with a manufacturer’s gross laden weight of 3.5 tonnes or more. Vehicles that use gasoline compressed natural gas, or liquified petroleum gas, are not included because they pay for their road use through fuel taxes. EVs are exempt from the program and do not pay a road user charge. [Note 6]

The RUC is administered through a pre-pay system with the purchase of distance licenses, each license allowing for 1000km of travel.

Interoperability

In addition to administrative interoperability between the federal and state pilots, cooperation is needed between states to properly charge vehicle owners who traverse state lines. In its simplest form, federal fuel tax replacement only requires an odometer reading and can be location agnostic. However, more is needed to accurately administer a state-level VMT fee, especially for states that experience large amounts of interstate travel. The federal government will likely need to consider and regulate these interstate transactions of data and funds. In some programs, pilot participants who drove out of state could apply for a refund for those miles driven. This manual process will become overly burdensome when VMT-fee program participation is made mandatory. Oregon and California have explored what complimentary programs could look like through an interoperability study as part of the OReGO program and California RUC pilot; a cloud-based clearinghouse was used to reconcile funds across state lines. [Note 7] However, it is important to note that this reconciliation requires a GPS reporting method, which many pilots found some of their participants felt unease toward due to privacy concerns.

The current fuel tax agreement with heavy vehicles may provide a model for interoperability when driving across state lines. The International Fuel Tax Agreement (IFTA) was created in 1991 with the passage of the Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act (ISTEA). Before IFTA, each state had its own fuel tax system for heavy vehicles and a truck needed to buy permits for each state that it drove through. IFTA simplified this system by allowing truck operators to file and pay in their home state, and then the money would be redistributed based on where fuel had been purchased and miles had been driven.

The International Registration Plan (IRP) also simplified the commercial vehicles registration process. [Note 8] While there are aspects of this system that would become more complicated with the introduction of private vehicles, IFTA and IRP’s coordination structures and redistributions can act as a model for state-to-state interoperability.

European Countries

Nine European Union (EU) countries have deployed RUC programs, including Austria, Czechia, Germany, and Switzerland, with an additional 11 evaluating a possible scheme. These programs are primarily aimed at “heavy goods vehicles” (HGVs), and use on-board devices to administer the RUC. [Note 9]

The EU has established a framework to encourage member states to “use taxation and infrastructure charging in the most effective and fair manner in order to promote the ‘user pays’ and ‘polluter pays’ principles, as enshrined in the treaties.” [Note 10] Germany attempted to implement a road user charge for passenger vehicles on its federal roadways, but it was rejected by the European Court of Justice as it would have penalized non- residents by charging them more. [Note 11] Norway piloted a RUC for passenger vehicles, but it has not yet been implemented. [Note 12]

Note 1: Federal Highway Administration, “Surface Transportation System Funding Alternatives (STSFA) Program Funding Awards,” U.S. Department of Transportation, February 9, 2022. https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/stsfa/funding_awards.htm

Note 2: Hawaii State Legislature, S.B. 1534, 32nd Legislature, 2023. https://www.capitol.hawaii.gov/session/measure_indiv.aspx?billtype=SB&billnumber=1534&year=2023

Note 3: Oregon State Legislature, H.B. 3297, 82nd Oregon Legislative Assembly, 2023. https://olis.oregonlegislature.gov/liz/2023R1/Measures/Overview/HB3297

Note 4: The Eastern Transportation Coalition, “Exploration of Mileage-Based User Fee Approaches for All Users,” February 2022 https://tetcoalitionmbuf.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Exploration-of- Mileage-Based-User-Fee-Approaches-for-All-Users_Condensed-1.pdf

Note 5: Susan J. Binder, “Road User Charge: Applying Lessons Learned in New Zealand to the United States,” Cambridge Systematics Inc, February 2019. https://onlinepubs.trb.org/Onlinepubs/NCHRP/docs/NCHRP2024(121)_NZ_RUC_Lessons_Learned _Report.pdf

Note 6: New Zealand Transport Agency, “About RUC.” Accessed June 30, 2023. https://www.nzta.govt.nz/vehicles/road-user-charges/about-ruc/

Note 7: RUC West, “Measuring Miles Beyond State Borders.” Accessed July 3, 2023. https://www.rucwest.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/RUC_Interoperability_folio_final-LTR.pdf

Note 8: International Registration Plan Inc, “Mission of IRP, Inc.” Accessed July 3, 2023. https://www.irponline.org/page/Missionpage

Note 9: Saeeda Malik, “RUC: Learning from the European experience,” Ptolemus Consulting Group, August 31, 2022. https://www.ptolemus.com/insight/ruc-learning-from-the-european- experience/#:~:text=Where%20in%20Europe%20is%20RUC,Czech%20Republic%2C%20Belgium%2 0and%20Bulgaria

Note 10: Directorate-General for Mobility and Transport, “Road charging,” European Commission. Accessed June 20, 2023. https://transport.ec.europa.eu/transport-modes/road/road-charging_en

Note 11: Deutsche Welle, “EU Court Rules Against Autobahn Tolls,” June 18, 2019. Accessed June 30, 2023. https://www.dw.com/en/eu-court-rules-against-autobahn-tolls/a-49243318

Note 12: Adam Hill, “Kapsch Pilots Norway RUC Project,” ITS International, November 15, 2022. Accessed June 30, 2023. https://www.itsinternational.com/its1/news/kapsch-pilots-norway-ruc-project