The following is an overview of the final compromise FAA reauthorization bill released in the wee hours of September 22, broken down into five areas: funding authorizations, airline customer service, aviation safety, airports, and unmanned aviation systems.

The House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee has released a more detailed section-by-section summary of the bill here. Remember – always check the official bill text here and, in instances where the bill amends existing portions of the United States Code, check the underlying code section at uscode.house.gov

OVERVIEW OF THE FAA REAUTHORIZATION ACT OF 2018 (DIVISION B OF HOUSE AMENDMENT TO SENATE AMENDMENT TO H.R. 305)

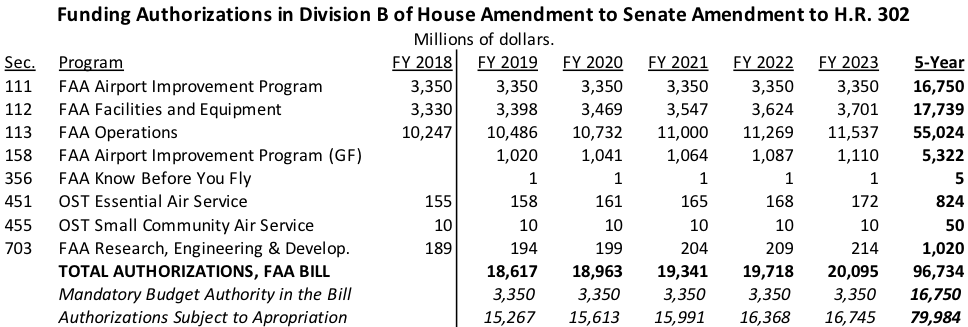

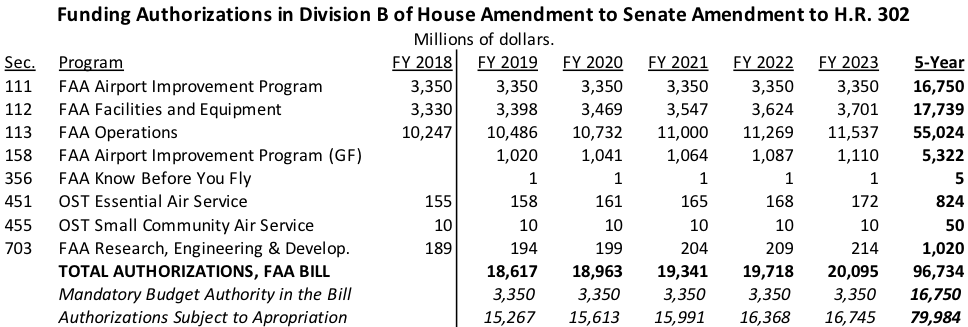

Funding authorizations. The final legislation authorizes a total of $96.7 billion in funding for federal aviation programs over five years (FY 2019-2023). This is the longest funding authorization period for Federal Aviation Administration programs since the 1982 act.

$16.8 billion of that amount is actually provided in the legislation itself in the form of contract authority for airport grants drawn on the Airport and Airway Trust Fund. The remaining $80.0 billion is to be appropriated in annual appropriations bills over five years.

The AIP contract authority is once again flat-lined at $3.350 billion for the duration of the legislation. This means that the program will have been stuck at $3.35 billion for 12 years (FY 2012-2023) and was at $3.50 billion for several years before that.

House T&I members on a bipartisan basis wanted to increase this level, but the Budget Committee and House GOP leadership overruled them on the way to the House floor. And the last version we saw of the Senate bill increased funding to $3.750 billion per year, but the final version is still stuck at $3.350 billion.

Now, the Appropriations Committees did add a $1.0 billion supplement to AIP in 2018, and the pending bill authorizes the appropriation more of that emergency aid starting at $1.02 billion in 2019, but if there isn’t another gonzo two-year budget deal raising the budget caps starting in 2020, that money will never materialize after 2019. (The pending appropriations bills for 2019 contain $500 million (House) and $750 million (Senate).)

As in the House version of the bill, section 115 of the final legislation repeals 49 U.S.C. §48112, so no matter what the Appropriations Committees wind up appropriating in future years, there will be no more “pop-up” AIP contract authority created which the appropriators could then rescind to offset more money for something else.

Pop-up contract authority was a legacy of the 2000 AIR-21 Act, and the pending bill in section 116 also sunsets the annual Airport and Airway Trust Fund minimum guarantee in 49 U.S.C. §48114 created by AIR-21, making FY 2018 the last year to which the guarantee applied.

Title VIII of the legislation also extends Airport and Airway Trust Fund spending authority, and the current law AATF excise taxes, from October 1, 2018 through September 30, 2023, without change.

Airlines – customer service. There are a great number of provisions in the final bill relating to airline customer service, many of them ripped from the headlines that have occurred during the three-year period during which Congress has had this legislation under consideration.

- Cell phones. The bill in section 403 orders a ban on passenger engaging in voice communications while on airplanes (Sen. Lamar Alexander, rejoice).

- E-cigarettes. Section 409 of the bill bans the use of electronic cigarettes while on airplanes.

- Pets. After the recent incident where a dog died in an overhead storage bin, section 417 of the bill makes it illegal to put live animals in overhead bins.

- Involuntary removal. After that incident where a gate agent let overbooked passengers onto a plane and then security had to drag a doctor, kicking and screaming, off of the plane, section 425 of the bill prohibits airlines from denying a revenue passenger traveling on a confirmed reservation permission to board once checked in and once their ticket is scanned by the gate agent, and prohibits airlines from involuntarily removing such passengers once boarded.

- Seat size. Section 577 of the bill requires the FAA to issue rules establishing minimum width, length and seat pitch of airline seats.

- Lavatory number and size. Section 426 of the bill directs GAO to study and quantify the shrinking number and sizes of airliner lavatories.

- Service animals. In response to widely reported abuse of the service animal requirements, section 437 of the bill requires DOT to issue a rule defining what qualifies as a service animal, including minimum standards for the same.

- Strollers. Section 412 of the bill prevents airlines from denying passengers the ability to check strollers at the departure gate unless the size or weight of the stroller poses a security risk.

- Air ambulances. There are several provisions relating to medevac helicopters – sec. 418 establishes an interagency advisory committee on air ambulance billing, sec. 419 requires each medevac company to tell passengers how to file complaints with DOT, and sec. 420 requires a DOT report to Congress on air ambulance oversight.

- Fee refunds. Section 421 requires DOT to issue a rule forcing airlines to refund ancillary fees paid by passengers for “services related to air travel that the passenger does not receive, including on the passenger’s scheduled flight, on a subsequent replacement itinerary if there has been a rescheduling, or for a flight not taken by a passenger.”

- Ombudsman. Section 424 of the bill requires the creation of a new Aviation Consumer Advocate position within the Office of the Secretary.

- Widespread panic. Section 428 requires airlines, in the event of a “widespread disruption,” to immediately post on their website information on whether and how the airline is arranging for hotels, ground transportation, meals, etc.

- Bill of rights. Section 429 of the bill requires airlines to post on their websites a summary 1-page document summarizing passenger rights, and section 434 does the same for disabled passengers.

- Reviews of possible future policy changes. In several areas, the bill stops short of mandating a new policy and instead requires DOT/FAA to review whether or not policy should be changed. These include sec. 406 (review of whether or not to force airlines to disclose the projected time between actual wheels-off and wheels-on), sec. 410 (baggage reporting), consumer protection enforcement standards (sec. 411), how airlines categorize the causes of delays and cancelations (sec. 413), compensation for changed intermarries (sec. 414), whether to give advance boarding to all pregnant women (sec. 422), and sec. 432 (review of possible in-cabin wheelchair restraint systems).

Aviation safety. With the exception of the regulation of drones and the certification of aerospace manufacturers and equipment (dealt with elsewhere in this summary), the major aviation safety reforms in the final bill can be broken up into several categories.

- Flight crew issues. Section 335 of the final bill orders the FAA to amend its hours-of-service rule for flight attendants so that a flight attendant scheduled to a duty period of 14 hours or less is given a scheduled rest period of at least 10 consecutive hours and the rest period is not reduced under any circumstances. It also requires airlines to produce fatigue risk management plans for its employees. There are several provisions relating to sexual harassment in-flight (sections 339A and 339B) and a new federal criminalization of assaulting flight crews (sec. 339). In the aftermath of the fatal hot air balloon crash in Texas in July 2016, section 318 of the bill directs the FAA to set more stringent safety standards for balloon pilots. Section 315 of the bill establishes an aviation rulemaking committee to review, and develop findings and recommendations regarding, pilot rest and duty rules on commuter and air taxi aircraft. And section 326 requires the FAA to mandate better training for flight crews on how to react to incidents of smoke or fumes on flights.

- FAA personnel issues. The final legislation includes provisions allowing new e-learning training curricula for FAA employees (sec. 302), a required update of FAA’s safety critical staffing model (sec. 303), and a review of how FAA selects and regulates the pilot examiners chosen to approve new pilots for their licenses (sec. 319).

- Safety of cargo carried on planes. Section 333 of the bill settles the lithium battery issue for the time being. It directs FAA to conform U.S. regulations on the air transport of lithium cells and batteries with the lithium cells and battery requirements in the 2015–2016 edition of the ICAO Technical Instructions (to include all addenda), including the revised standards adopted by ICAO which became effective on April 1, 2016 and any further revisions adopted by ICAO prior to the effective date of bill. It also directs FAA to expeditiously approve or reject waiver requests for lithium-powered medical devices and work with PHMSA on those procedures, and also provides for limited mandatory waivers allowing a few medical device batteries to be shipped as cargo on planes to remove areas that don’t get regular air cargo service.

- Safety data reported to the FAA. Section 311 of the bill requires a study of how much extra safety data the FAA should demand from commuter and air taxi carriers. Section 320 requires the FAA to presume as valid voluntary individual reports of safety violations. Section 314 requires additional data reporting from air ambulance providers.

- Safety equipment on aircraft. In light of what happened with Malaysia 370, section 305 orders a review of standards for flight recorders and their retrieval in planes that will have extended overwater operations. The bill requires reviews of the safety of cockpit heads-up displays (sec. 306), emergency medical equipment carried on airliners (sec. 307), and of engine safety (sec. 309). Section 317 requires better crashworthiness standards for the fuel systems in helicopters. And section 336 requires the installation of secondary cockpit barriers on all new airliners starting one year after enactment.

- Safety equipment on the ground. The bill calls for FAA to install more approach control radar (sec. 327) and to stop requiring the use of fluorinated chemicals in firefighting foam (sec. 332). And section 313 requires the FAA to study if ground safety equipment is marked well enough so that pilots can always see it.

- General aviation safety. Section 308 requires a comprehensive FAA-NTSB review of GA safety. And subtitle C of title III of the bill is devoted to GA safety, but mostly by increasing the rights of GA pilots to get access to NTSB and FAA information on their flight incidents and accidents, get better notice of when and why the FAA wants them to get a new examination, and by forcing a hesitant FAA to fully implement section 3 of the Pilot’s Bill of Rights relating to NOTAM access.

- Miscellaneous. Section 323 requires the FAA to study whether or not allowing airliners to fly with unoccupied exit rows is really safe.

Airports. The airports did not get their big “ask” – an increase in the passenger facility charge (PFC) that airports can levy on enplaning passengers, which has been capped at $4.50 per passenger per segment since 2000 (like the gas tax, the PFC is not indexed for inflation). This was pretty much a foregone conclusion, since the House-passed bill contained no PFC increase and the bill reported from committee in the Senate did not include one, either. (The FY 2018 Transportation-HUD appropriations bill in the Senate did allow the airport of origin to increase PFCs (but not airports where one simply changes planes), but that was dropped in the FY 2019 bill.)

And, as mentioned above, the final bill continues the flat-lining of funding for the Airport Improvement Program of grants to airports at $3.35 billion per year through 2023. (AIP is more important to medium-to-small airports – the big airports make much more money from their PFCs than they do from the AIP program.)

Instead, the airports get a provision (sec. 121) making it easier to levy PFCs of $4.00 or $4.50 without the extensive justification process currently required, and that section also allows hub airports access to the alternative PFC approval process pilot program. Airports also get a big study of future airport funding needs that will, presumably, give the blue-ribbon seal of approval to recommendations for a PFC increase in the next authorization bill in 2023. Section 122 requires an outside organization (TRB?) to conduct a comprehensive study of the infrastructure needs of airports. (Although section 143 of the bill also requires GAO to study if airports are diverting fuel tax receipts to non-aviation purposes.)

And as mentioned above, after the two-year budget deal struck in February 2018 gave the Appropriations Committees more money than they knew what to do with, the FY 2018 appropriations act for USDOT gave an extra $1.0 billion from the general fund for the AIP program. Section 158 of the bill provides statutory authorization for future appropriations like that at the CBO baseline levels, but after 2019, any extra AIP money from the general fund is dependent on the negotiation of a future deal increasing the BCA caps.

Other significant airport-related provisions in the final bill include a provision (sec. 132) requiring airports to provide private lactation rooms, significant reforms to the contract tower program (sec. 133 and sec. 152), an increase in the federal share of AIP projects at certain airports (sec. 134), a new pilot program allowing up to 6 airports to use AIP grants for environmental mitigation (sec. 190), expansion of the project delivery streamlining program to include general aviation airports (sec. 191), and a lot of provisions that appear targeted to individual airports but don’t actually name those airports.

Section 159 of the bill forbids states and cities from levying any tax on a business at an airport “that is not generally imposed on sales or services by that State, political subdivision, or authority unless wholly utilized for airport purposes.”

And section 160 of the bill expands the existing airport privatization pilot program to include more than 10 airports, allows airport sponsors that operate multiple airports to participate, and allows airports to use up to $750 thousand of their AIP grant money to prepare applications to enter the privatization program. In addition, section 184 of the bill makes privatized airports in the pilot program eligible for AIP funding from the discretionary fund, and a letter of intent can be issued but only for a project approved in FY 2019.

There are also several provisions relating to airport noise (sec. 173 requires evaluation of alternative noise metrics, sec. 174 requires airports to submit revised noise exposure maps if they change airport operations, and sec. 175 orders the FAA to “consider the feasibility” of changing flight patterns in certain circumstances). And there are at least a half-dozen new studies and reviews ordered relating to noise issues.

Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS) (a.k.a. Drones). Provisions regarding UAS take large role in the bill, setting up the future of the FAA as it attempts to fully integrate the airspace with the growing number of unmanned aircraft. Much of the provisions below add to the groundwork laid in 2012, but there are some notable additions and clarifications. Most of the UAS subject matter is under the Safety title (Title III), Subtitle B; the 2012 bill had 6 sections under Title III, Subtitle B, the 2018 bill has 44.

- Safety Oversight and Certification Advisory Committee. Section 202 codifies the committee already established by the FAA, and requires that at least one of the committee members represent the UAS industry (a UAS operator or manufacturer)

- FAA Task Force on Flight Standards Reform. Section 222 creates a task force to provide the Secretary with advice on how to reform flight standards. At least one of the 20 members must come from the UAS industry.

- Additional definitions. The definition section adds to the definitions outlined in the 2012 FAA Reauthorization Bill, and include tethered unmanned aircraft, counter-UAS system, technology, and unmanned traffic management (UTM). The definitions retain the weight-based categories of UAS.

- Update on FAA Comprehensive Plan. Section 342 requires that the FAA update its comprehensive plan, and include details on UTM and rules for reporting illegal or dangerous UAS activity.

- Unmanned aircraft test ranges. Section 343 requires the FAA to continue its test range program.

- Small unmanned aircraft in the artic. The bill retains the program for deploying commercial and research aircraft in the Arctic on a permanent basis.

- Small unmanned aircraft safety standards. Section 345 requires the FAA to establish a process for accepting risk based, consensus safety standards related to design, production, and modification of small UAS. It also establishes a prohibition for false certifications.

- Public unmanned aircraft systems. Section 346 allows the FAA to authorize government agencies seeking to operate unmanned aircraft for activities such as police and firefighting.

- Special authority for unmanned aircraft systems. Section 347 allows the FAA to permit UAS to operate under “special authority,” including beyond visual line of sight. As part of the permit, the agency is required to use a “risk-based approach” to determine if the aircraft can safety navigate.

- Carriage of property by small UAS. Section 348 requires FAA to update requirements to allow for commercial operation of small UAS to deliver packages or other commercial products for hire. The rulemaking must include “performance-based requirements,” and risk assessment.

- Exception for hobby aircraft. Section 349 sets rules for recreational operations of unmanned aircraft, including that the flyer keep the UAS away from other aircraft, keep it below 400 feet above ground level, and pass an aeronautical knowledge test.

- Codification of the UAS Integration Program. Section 351 the DOT-created UAS Integration Program, and requires that FAA report the results of that program to Congress

- UAS Reports. Several sections require FAA to submit reports to Congress on pressing issues related to UAS. Sections 357 and 358 relate to UAS privacy concerns. Section 359 requires a report on the use of UAS for fire and police activities. Section 360 requires a comprehensive study on the financing of UAS, including the costs of administration, regulation and air traffic management (UTM) for both now and in the future.

- UAS punishments. Sections outline stiff punishments for illegal UAS operation over wildfires, near airports, and in other restricted airspace.

- UAS and the workforce. Title VI, subtitle D creates several programs to train youth and those entering the workforce to design, operate, and control UAS.

- UAS threat elimination. Division H of the bill gives DOT, the Attorney General, and in some cases the Coast Guard the authority to destroy or overtake a UAS that has violated protected airspace or is otherwise posing a threat to the safety or security of the U.S.