A new study from the RAND Corporation, commissioned by Congress in 2018, recommends that the statutory maximum passenger facility charge (PFC) levied by airports be increased from $4.50 per passenger to $7.50 per passenger, that the increase be limited to originating airports only, and that the new $7.50 cap be indexed for inflation (tied to the Producer Price Index for construction materials) thereafter.

Background: In 1967, the Evansville, Indiana airport had a novel idea – charge a “head tax” on enplaning passengers of $1 per passenger to help offset airport expenses. New Hampshire followed suit in 1969 with a state law levying a similar $1 head tax on enplanements at any public airport in the Granite State. Airlines quickly filed lawsuits, protesting that state and local officials could not tax interstate commerce. In April 1972, the U.S. Supreme Court held, in Evansville-Vanderburgh Airport Authority Dist. v. Delta Airlines, Inc. (405 U.S. 707) that the head taxes were constitutionally permissible.

The airlines then went to Congress, which promptly passed a bill banning airport head taxes in October 1972, which was pocket vetoed by President Nixon for other reasons, but a revised version was signed into law in June 1973 (section 7 of Public Law 93-44).

The ban stayed in place for eighteen years, until title IX of the 1990 budget deal (Public Law 101-508) reauthorized the airport development program, and section 9110 of the law authorized airports to collect their own revenue once again, this time called a passenger facility charge, of up to $3.00 per enplaned passenger. PFC revenues could be used to pay for airport projects directly, or to pay for debt service on bonds that pay for airport projects (which is mostly what they are used for today). The charges were to be collected by the airlines (added to the cost of a ticket, along with federal taxes) and then given to the airport.

Ten years later, the 2000 AIR-21 reauthorization law (Public Law 106-181) increased the maximum allowable PFC from $3.00 to $4.50. The ceiling has not been increased since then. Airports have consistently advocated an increase in the cap (or repeal of the cap altogether), but opposition from airlines (who don’t like being forced to collect the fees) and from anti-tax conservative groups has stymied the airport efforts.

Airports thought they were going to get a PFC cap increase in the Senate version of the 2018 FAA reauthorization bill, but that fell apart at the last minute. Instead, the airports got…a study.

Section 122 of the FAA Reauthorization Act of 2018 (Public Law 115-254) required the Department of Transportation to hire an “independent nonprofit organization that recommends solutions to public policy challenges through objective analysis” to conduct “a study assessing the infrastructure needs of airports and existing financial resources for commercial service airports and make recommendations on the actions needed to upgrade the national aviation infrastructure system to meet the growing and shifting demands of the 21st century.”

USDOT hired the RAND Corporation, and the study, entitled U.S. Airport Infrastructure Funding and Financing (main report here and appendices here) was released this week.

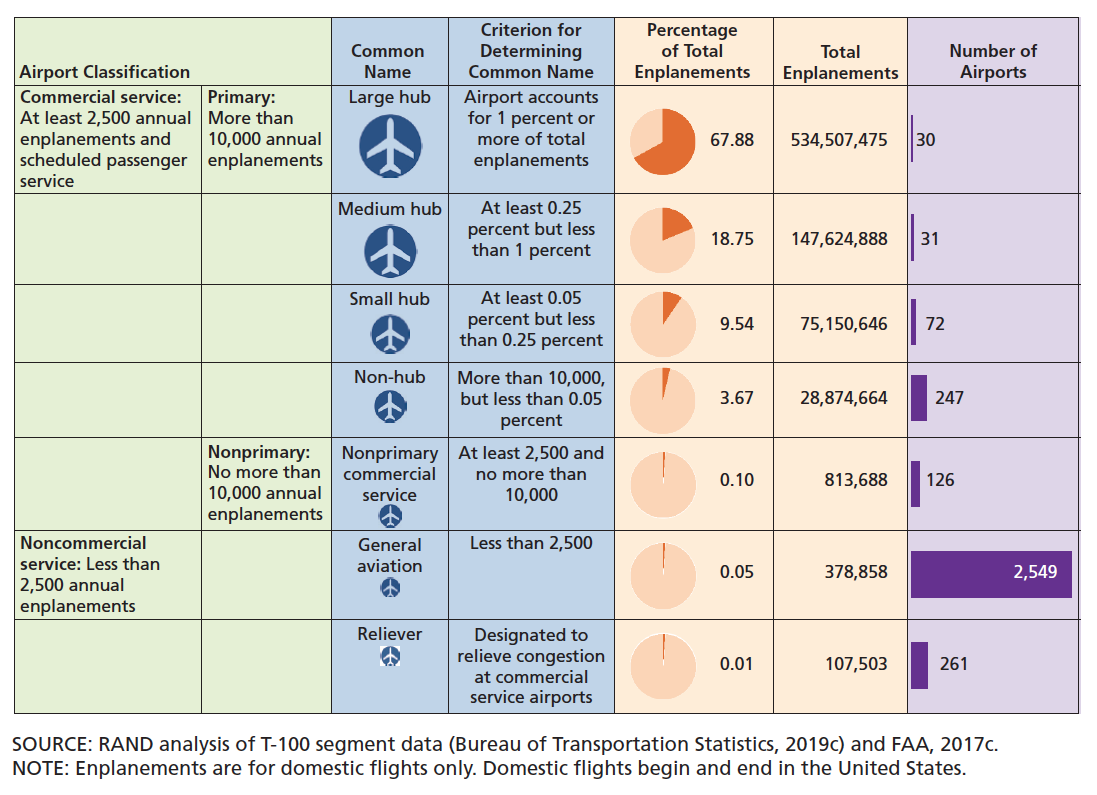

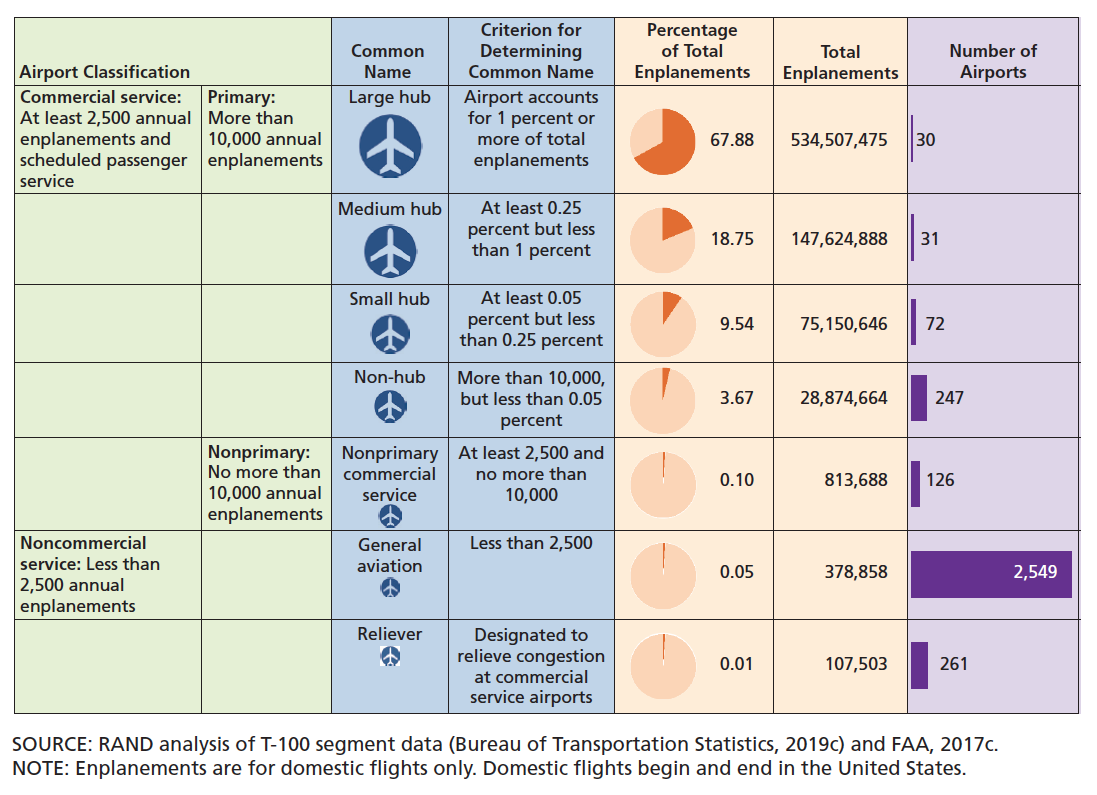

Findings of the study. The RAND study contains a wealth of data on U.S. airports – their traffic, their funding needs, and their revenue sources. To begin with, a nifty infographic showing an overview of the extent of the U.S. airport network (from Table S-1 in the report):

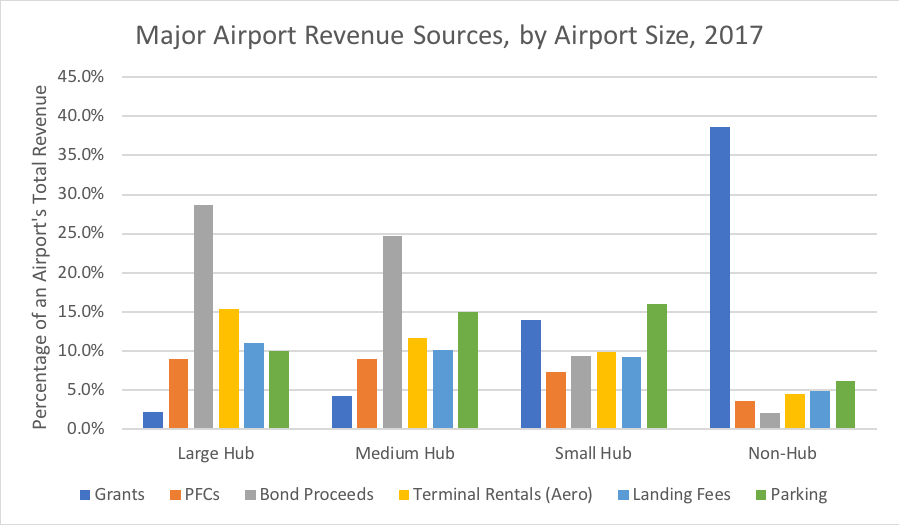

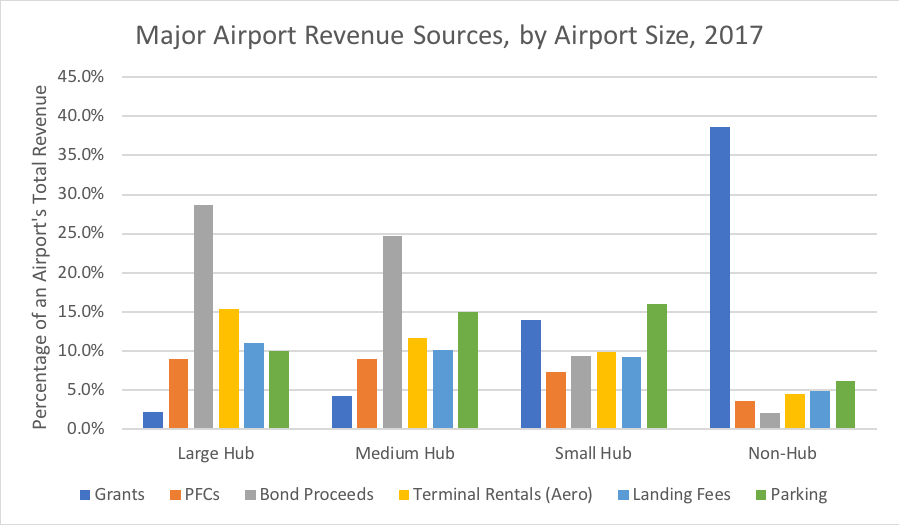

The revenue sources available to the 30 large hub airports are very different from the revenue sources relied on by the 247 non-hub primary airports, as this graphical distillation of the data from Table D.2 in the appendix to the study shows:

Large hubs only relied on federal and state grants for 2.2 percent of their total revenues in 2017, while such grants were 38.7 percent of the revenues for non-hub primary airports. Moving in the other direction, non-hubs can’t really issue bonds reliably (bond proceeds were 2.1 percent of non-hub revenues versus 28.6 percent of revenues for the 30 large hub airports).

Part of that difference is PFCs, which are reliable long-term revenue streams that airports can borrow against with bond issuances. PFC receipts were 9.0 percent of large hub revenues in 2017, 8.9 percent of medium hub revenues, and 7.3 percent of small hub revenues, but that dropped down to just 3.6 percent of non-hub primary airport revenues. A better way to put it is in dollars, from Table D.1 of the appendix to the report:

| Major Airport Revenue Sources, by Airport Size, 2017 (Million $) |

|

Large Hub |

Med. Hub |

Small Hub |

Non-Hub |

| Grants |

601 |

245 |

425 |

650 |

| PFCs |

2,429 |

525 |

228 |

88 |

| Bond Proceeds |

7,734 |

1,447 |

306 |

46 |

| Terminal Rentals (Aero) |

4,144 |

688 |

311 |

107 |

| Landing Fees |

2,980 |

591 |

290 |

92 |

| Parking |

2,706 |

882 |

549 |

149 |

That $88 million in PFC revenue collectively raised by the 247 non-hub primary airports won’t secure a lot of bonds. But the $2.4 billion in PFC revenue amongst the top 30 large hub airports can securitize quite a bit. And since those bonds usually fall under the municipal government category that pay interest that is exempt from federal income tax, airports can often issue bonds at quite low interest rates, giving those PFCs a high “bang for the buck” when used to pay debt service.

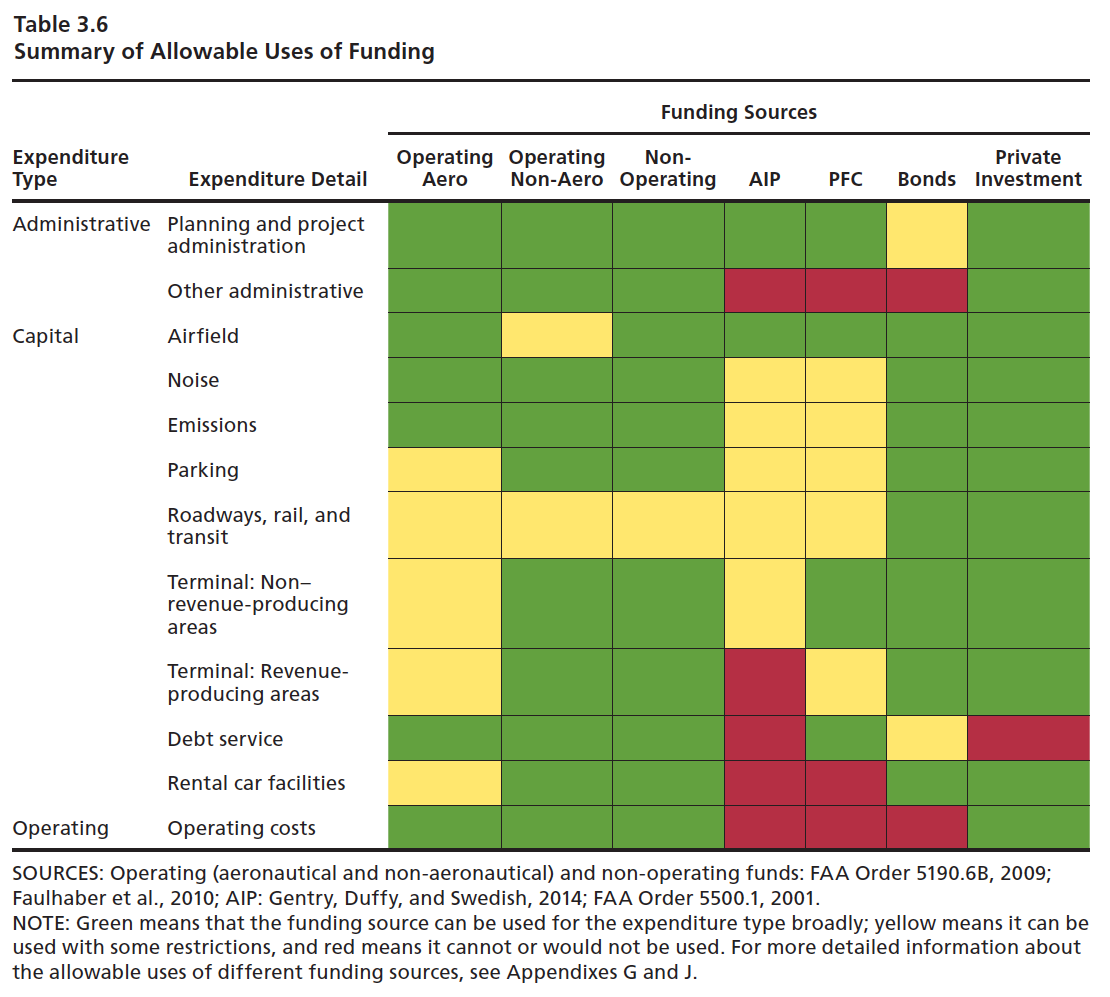

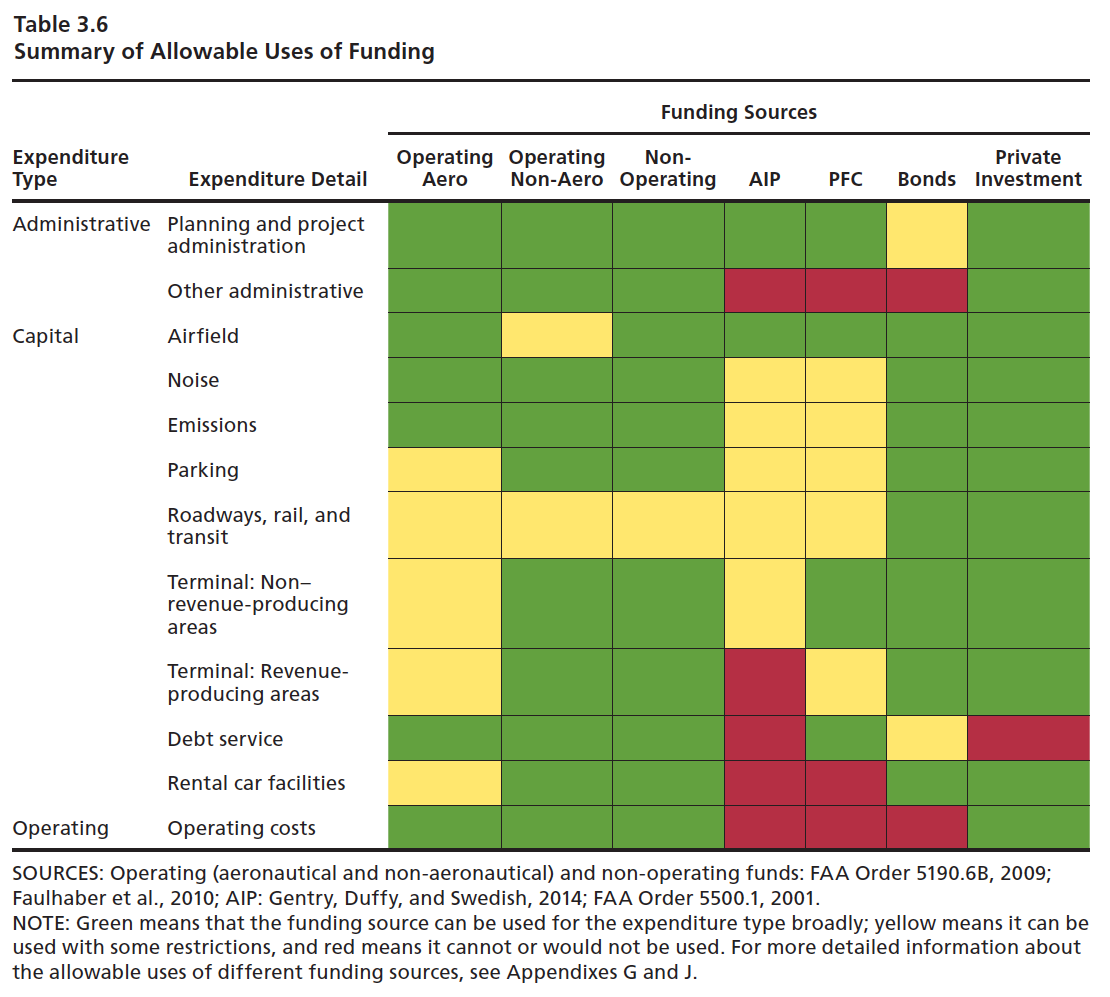

Different kinds of airport revenue are subject to different kinds of restrictions on the use of that revenue. Table 3.6 from the RAND report gives a good overview:

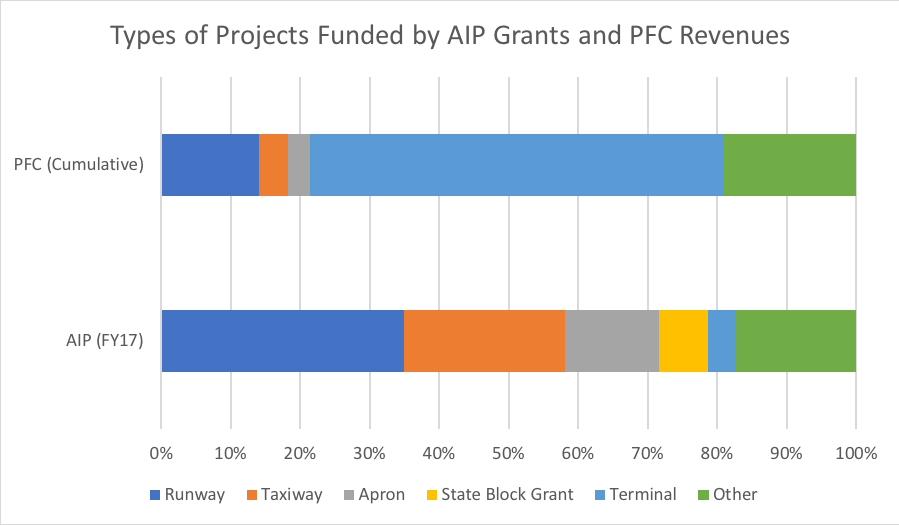

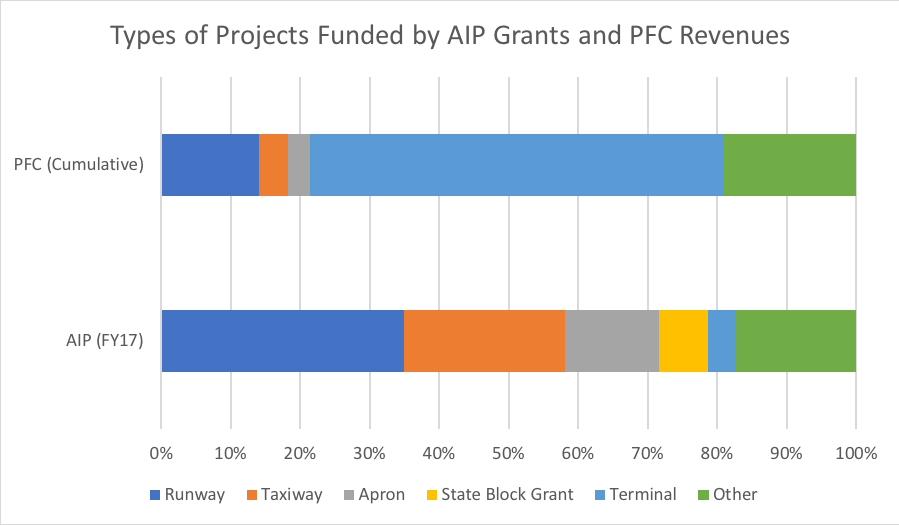

These various revenue sources supported $33.75 billion in spending by airports during 2017 (see Table 4.2 in the study for a breakdown). When one isolates the usages of the federal Airport Improvement Program (AIP) grants in 2017 and the eventual usages of PFC receipts (counting payments of bonds as spending on the projects paid for by the bond issuance), there are significant differences. The chart below (assembled with information from Table G.1 and Appendix H in the appendix to the report) shows that airports spent 72 percent of the AIP money on runways, taxiways, and aprons versus just 3.9 percent on terminals. But of the cumulative PFC funding over the years, almost 60 percent has been spent on terminals versus just 21 percent on runways, taxiways and aprons.

The report found that more investment, overall, is needed: “a small number of capacity-constrained airports and airport pairs appear to be responsible for delays that could be partially (but not fully) addressed by sound infrastructure investment. Twenty airports (19 large hubs and one reliever) accounted for 96 percent of delays measured by the FAA’s Operations Network in 2018. The top five airports alone, three of which are operated by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey (LaGuardia Airport, John F. Kennedy International Airport, and Newark Liberty International Airport), accounted for 61 percent of delays. These delays propagate through the NAS: A flight delayed in arriving at its initial destination might be late departing for its next destination. Some of this congestion could be addressed in part through sound investments in reconfiguring or expanding infrastructure on both the airside and the landside.”

The report notes that the PFC has lost a lot of its buying power since it was last increased in 2000:

The purchasing power of the maximum per-enplanement PFC has declined, from $4.50 in 2000 to $2.72 in 2018, expressed in year 2000 dollars indexed to construction prices. If the $4.50 PFC cap had been indexed to inflation in construction prices in 2000, the current cap on passengers would be $7.44.

(Ed. Note: Kudos to RAND for using an inflation index other than CPI, because CPI is worthless for figuring out lost buying power when we are talking buying concrete and asphalt and structural steel, acquiring land, using earthmoving equipment and prevailing-wage labor, etc.)

Recommendations. When looking at PFC issues, the report considered four options:

- Option A: Index the existing $4.50 cap for inflation moving forward.

- Option B: Increase the cap from $4.50 to $4.75, index for inflation moving forward, and reduce statutory AIP entitlements by $1.00 per passenger at airports that choose to increase their PFC (to give more AIP money to non-PFC-reliant airports). (However, airports that charge a $4.50 PFC already give up 75 percent of this entitlement, so they only receive $0.25 per passenger in practice for enplanements above 1 million, up to a statutory cap on primary entitlements.)

- Option C: Increase the cap from $4.50 to $7.50 (for originating passengers only – passengers changing planes would only be charged the original $4.50), index for inflation moving forward, and eliminate 100 percent of AIP primary entitlements for medium- and large-hub airports that choose to raise their PFC above $4.50.

- Option D: Remove the PFC cap for originating flights only, index the $4.50 cap for layovers to inflation, and eliminate 100 percent of AIP primary entitlements for any airports that choose to raise their PFC above $4.50.

The report recommended Option C. They rejected Option A because “it does not improve the ability of constrained airports to meet growing needs in the near term.” They rejected Option B because it “would not help those airports that have demonstrated needs to raise additional revenue to meet higher demand” – even though it would free up some AIP revenue for less-traveled airports.

And they rejected Option D because of concerns that “airports would burden their customers and airlines’ passengers with the cost of unnecessary projects…As experience over the past two decades showed, virtually all airports raised their PFC to the cap over time. However, we do not see a rationale or signs of demand for entirely removing the cap.”

Here are some of the report’s reasoning behind choosing Option C:

We are not aware of compelling evidence or data justifying a particular level for a new cap. Any number could be chosen, but we note that if the $4.50 cap had been indexed to inflation in 2000 using the Producer Price Index for construction materials, it would now be set at $7.44. For this reason, we suggest that the cap in this option be around this value, perhaps rounded up to $7.50, although other levels could be chosen. Although an increase in the PFC cap would likely result in higher ticket prices for passengers traveling through airports that raised their PFC collections, there remains in place a set of guardrails to weigh the public benefits of PFC-funded projects relative to the costs imposed on passengers. Airports will continue to be required to justify the net benefits of projects proposed for PFC funding to the FAA, and the FAA retains its discretion to approve or disapprove applications for these projects. Further, airports will still need to be responsive to comments from airlines and other stakeholders when requesting a PFC increase…

We recommend that large- and medium-hub airports that raise their PFC above $4.50, indexed to inflation, should forgo their AIP primary entitlements dollar-for-dollar for each dollar of PFCs they collect, up to 100 percent of these entitlements. Instead, that money could more efficiently achieve the redistributive purpose of the AIP by being either focused on the needs of national significance among smaller airports or directed to other priorities affecting the safety and sustainability of the NAS. Airports that raise their PFC above $4.50 would remain eligible for other categories of AIP funding, including cargo entitlements and discretionary awards.

We recommend that any increase in the PFC cap apply only to passengers who originate at that airport, while the PFC for layover passengers remains capped at $4.50, indexed to inflation. The rationale for restricting future PFC increases to origin passengers only is to ensure that airports that increase their PFCs do so at their own expense, rather than at the expense of other airports.

The report also made some other recommendations relating to potential changes in the AIP program and to the structure and practices of the Airport and Airway Trust Fund, which funds AIP and most other FAA expenses:

- AIP – Repeal the automatic doubling of primary entitlements per-passenger whenever annual AIP funding exceeds $3.2 billion. “As a consequence of this policy, annual AIP funding is spread across all primary airports according to their enplanements, and the FAA has less discretion to effectively direct funds to current high-priority projects at specific airports.”

- AIP – Congress should consider removing nonprimary entitlements. “…under current law, whenever Congress appropriates at least $3.2 billion to the AIP, each nonprimary airport in the NPIAS receives an entitlement of up to $150,000 instead of those funds going to more-flexible state apportionments for nonprimary airports. This amount is insufficient for major construction projects, and the existing state apportionment mechanism is both better suited to meet nonprimary airports’ needs and has sufficient oversight mechanisms in place.”

- AATF – Congress should avoid the accumulation of large uncommitted Trust Fund balances, while still maintaining a “rainy day” reserve fund. “In years that experience unusually low demand for air travel, such as 2002 and 2009, actual revenues to the AATF can fall approximately $2 billion below projected revenues. A rainy day fund containing $4 billion to $6 billion would be sufficient to ensure that AATF outflows, for all purposes, can remain stable even in the face of two to three years of severe revenue shortfalls. However, after seeding the rainy day fund, additional revenues should be appropriated to meet clearly identified needs, as determined by the FAA.”

- AATF – Congress should apply the domestic passenger ticket tax to ancillary fees like checked baggage, advance seat assignments, and priority boarding fees. “If the $4.9 billion in baggage fees collected by airlines in 2018 had been subject to the 7.5 percent tax, AATF revenues would have been about $367 million higher, all other factors being equal.” Current policy “favors airlines that separate ancillary fees from their base ticket price over those that do not. Airlines should be free to separate ancillary fees if they wish, but the Domestic Passenger Ticket Tax should not incentivize one business model over another by taxing ancillary services differently from bundled ticket prices. However, Congress should not be collecting additional AATF revenue without a commitment to spend it, as noted in the preceding recommendation. For this reason, we recommend that Congress ask the FAA to help determine the level of reduction in the Domestic Passenger Ticket Tax that would make the taxation of ancillary fees revenue-neutral.”

The report also recommends that the FAA consistently enforce existing rules against airports diverting airport operating revenue to non-airport purposes, and that Congress repeal the “grandfathering” exemptions for 12 airport sponsors issued in 1982. (The report quotes a 2018 USDOT Inspector General study saying that “[f]rom 1995 to 2015, grandfathered sponsors have reported over $10 billion in grandfathered payments in 2015 inflation-adjusted dollars, including over $1.2 billion in 2015”.)