The American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) yesterday requested $50 billion in emergency federal appropriations to compensate for lost state revenues due to the coronavirus’s effect on both travel and the broader economy.

In a letter to Congressional leaders, AASHTO asked Congress to “provide $49.95 billion as an immediate revenue backstop to state DOTs in order to prevent major disruptions in their ability to operate and maintain their transportation systems during this national emergency.”

In addition, the state DOTs are also asking Congress to enact a six-year, $800+ billion surface transportation reauthorization bill to “finally put us on the path to eliminate [the] longstanding investment backlog by the end of this decade while meeting arising asset condition and performance needs to support and sustain our multiyear economic recovery and growth.”

$50 billion in immediate funding.

Not a highway funding request. The AASHTO letter asks for $49.95 billion – but not as additional highway funding (which was how the 2009 ARRA stimulus bill worked). Instead, AASHTO wants the $50 billion in “backstop funds to be essentially treated as state revenues that would otherwise been collected for a wide range of state DOT activities without the COVID-19 pandemic. This broad funding eligibility would recognize the fact that state transportation revenues are used for any and all transportation activities undertaken by state DOTs.”

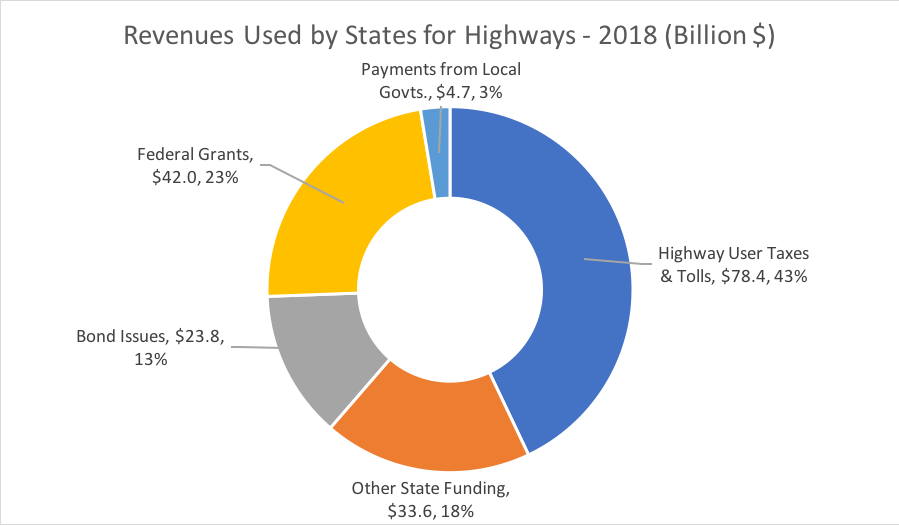

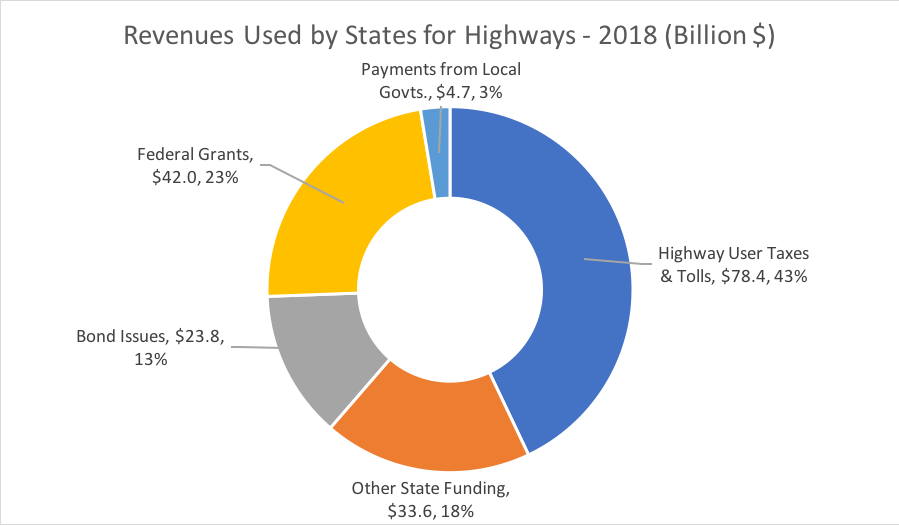

How did they come up with the $50 billion number? AASHTO says that they anticipate “at least a 30 percent decline on average [in state transportation revenues] for the next 18 months.” In the short term, this certainly seems accurate (at least according to INRIX data and other cell-phone-based tracking services). Here are the totals for all state revenues for highways in FY 2018, per the latest Highway Statistics Table SF-1:

That 2018 total was $182.6 billion. If you subtract the federal grants ($42.0 billion) and the local revenues kicked upstairs ($4.7 billion) and the bond issues ($23.8 billion), the 2018 total drops to $112 billion, and the AASHTO letter cites a 2019 total of $111 billion. AASHTO derives its $50 billion request as follows:

- For FY 2020 (which is half over), assume a 30 percent drop in state transportation revenues over the last six months of the fiscal year. $111 billion divided by 2 is $55.5 billion, times 30 percent is $16.65 billion.

- For FY 2021, multiply the full-year 2019 amount of $111 billion times a 30 percent reduction, to get $33.3 billion.

- $16.65 + $33.30 = $49.95.

No one questions that the current drop in highway use taxes is at least 30 percent at the moment and probably for the next couple of months at least due to to coronavirus lockdown. Expectations for how this will affect highway revenues in January 2021, much less September 2021, are much less certain. Here are the specific sources of the $112 billion in state non-bond highway revenues from 2018:

| Source |

Billion $ |

| Motor Fuel Taxes |

$35.74 |

| Vehicle/Motor Carrier Taxes |

$28.10 |

| Road/Crossing Tolls |

$14.56 |

| State GF Appropriations |

$8.08 |

| Other State Imposts |

$12.68 |

| Miscellaneous |

$12.88 |

| TOTAL STATE SOURCES |

$112.04 |

Not all of these are going to drop off at the same rate or the same time. When a person curtails their driving substantially, their fuel purchases and their toll payments drop immediately, but they don’t stop renewing their car registration or paying their personal property taxes. And, to the extent that any of this drop in revenues is expected to come from the state general fund appropriations or the miscellaneous category, aid for state DOTs should probably be viewed in the broader context of aid to state governments in general, since many of those revenue sources are fungible at the will of the state legislature.

No longer capital-focused. The federal role in the federal-aid highway program has always been largely confined to capital spending. The AASHTO letter says “State DOT operations and maintenance activities should be fully eligible for funds provided as the revenue backstop. This will enable states to help pay for unusually heavy expenses resulting from extraordinary conditions caused by COVID-19, ranging from meeting payroll for state DOT workforce to prevent furloughs or layoffs to improving remote-working systems to prevent IT system overload contributing to project delivery delays and increased costs.”

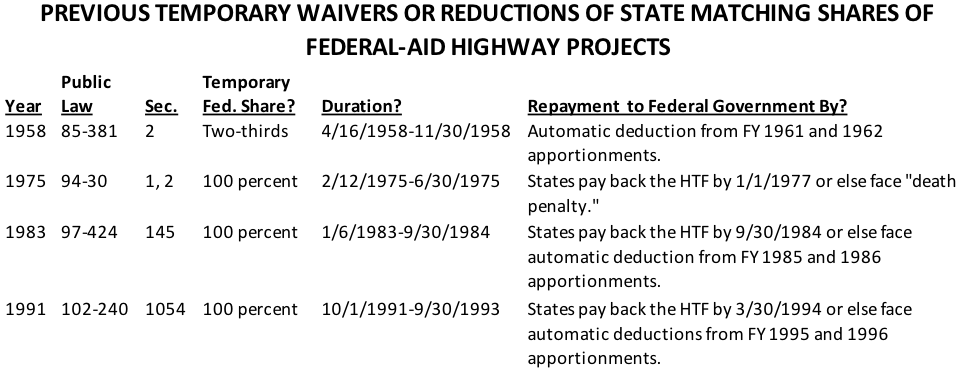

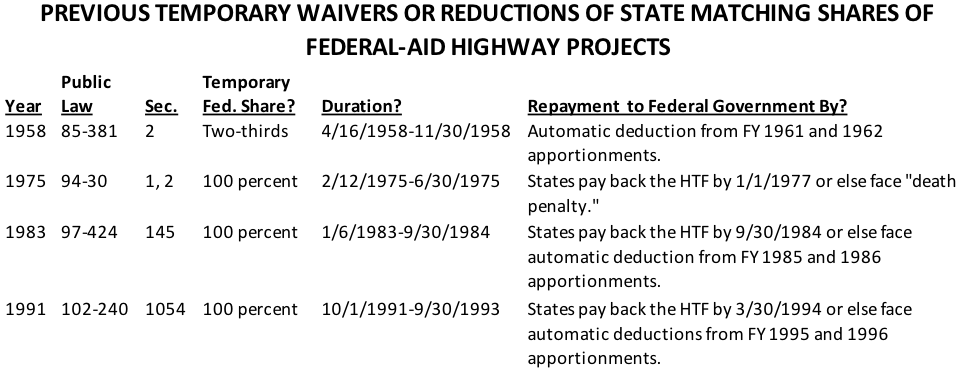

Boost the federal share to 100 percent temporarily. In past recessions, Congress has attempted to give state highway departments fiscal relief by temporarily increasing the federal share of highway project costs under the federal-aid program. In 1958, the federal share was temporarily increased from 50 percent to two-thirds, and in 1975, 1983, and 1991, the federal share was temporarily increased from 80 percent to 100 percent. However, in all those instances, states were expected to repay the federal government once the recession ended.

AASHTO asks Congress to increase the federal share of projects to 100 percent “in the near term” (undefined) and says “In addition to supporting immediate capital, operations, and maintenance needs at state DOTs, this feature will also provide states the necessary fiscal space to meet existing debt obligations.” (No word about the states having to pay back the money eventually.)

No “maintenance of effort” requirement. The 2009 ARRA stimulus law tried to ensure that the transportation stimulus money was in addition to money that state and local governments were going to spend anyway, not a substitute for such money. Section 1201 of the Transportation-HUD title of ARRA required “maintenance of effort” certifications from state governors, with a small financial penalty (ineligibility for the August 2011 highway redistribution) if states failed to so certify. The maintenance of effort requirement was largely a failure, as the data clearly shows that much of the ARRA highway money (at a 100 percent federal share) simply took the place of regularly scheduled state spending of regular federal highway dollars (with a 20 percent state match) in FY 2009-2011.

The AASHTO letter says “Taking lessons learned from past recovery efforts, we request Congress to not include maintenance of effort requirements and to avoid overlapping reporting and oversight requirements from multiple entities.” This makes sense, in that the new request is specifically not about economic stimulus, but about trying to maintain what states are already doing in the absence of anticipated revenues.

An $800+ billion surface transportation reauthorization bill.

The AASHTO letter then changes course and looks ahead to the reauthorization of federal surface transportation programs (which was due by September 30, 2020 even before COVID-19). Citing the new USDOT Conditions and Performance Report released four months ago, AASHTO cites a combined investment backlog of $902 billion ($786 billion in highway needs and $116 billion in transit needs).

In order to address the backlog, AASHTO then asks Congress to “double the amount of federal surface transportation funding and reauthorize these programs for at least another six years. These actions will finally put us on the path to eliminate this longstanding investment backlog by the end of this decade while meeting arising asset condition and performance needs to support and sustain our multiyear economic recovery and growth.”

The letter is not specific about what is exactly meant by “double the amount” (when you’re asking for the sun, moon and stars, you don’t take time to specify what phase of the moon), but this almost certainly means a six-year bill spending around $800 billion. Here are the FY 2020 enacted totals for the “surface transportation bill” agencies (which excludes the Federal Railroad Administration and Amtrak) and the extrapolated baseline projections, in millions of dollars:

|

FY 2020 |

FY 2021 |

FY 2022 |

FY 2023 |

FY 2024 |

FY 2025 |

FY 2026 |

6-Year |

|

Enacted |

Congressional Budget Office January 2020 Inflation-Adjusted Baseline |

| HTF Contract Authority/Ob. Limits |

58,667 |

59,887 |

61,175 |

62,466 |

63,754 |

65,100 |

66,391 |

378,773 |

| General Fund Appropriations |

5,087 |

5,244 |

5,359 |

5,478 |

5,592 |

5,715 |

5,832 |

33,220 |

| Total, FHWA-FTA-NHTSA-FMCSA |

63,754 |

65,131 |

66,534 |

67,944 |

69,346 |

70,815 |

72,223 |

411,993 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| FY 2020 Enacted Times 2 (Flat-Line) |

|

127,508 |

127,508 |

127,508 |

127,508 |

127,508 |

127,508 |

765,048 |

| CBO Baseline Times 2 |

|

130,262 |

133,068 |

135,888 |

138,692 |

141,630 |

144,446 |

823,986 |

Lowest-case scenario, it’s $765 billion over six years, and if you double the extrapolated baseline, it’s $823 billion over six years.

By contrast, the six-year total reauthorization that is part of the Trump Administration’s ten-year proposal for these same accounts is $436 billion. House Democrats are proposing $434 billion over a five-year period, not six years. $800-ish billion over six years is a significant jump above that.

The letter then reiterates many of the key policy principles for reauthorization adopted by the AASHTO Board last year, along with pleas for expansive Amtrak reauthorization and water resources development reauthorization bills.