March 29, 2017

March 23 marked the half-dozen mark for aviation hearings in the current session of Congress (here are the links to our coverage of the first, second, third, fourth, and fifth). This time it was the Subcommittee on Aviation Operations, Safety, and Security of the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation doing the honors, with a hearing about two distinct issues: airports, and aviation certification, two topics already covered by the House Transportation and Infrastructure (T&I) Committee.

The hearing had two different panels, the first discussing airports, and the second certification. The two witnesses of the first panel were:

- Rhonda Hamm-Niebruegge, Executive Director, St. Louis Lambert International Airport (statement here);

- Bob Montgomery, Vice President, Airport Affairs, Southwest Airlines (statement here).

The second panel had three witnesses:

- Peggy Gilligan, Associate Administrator for Aviation Safety, Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) (statement here);

- Gerald Dillingham, Director of Civil Aviation Issues, Government Accountability Office (GAO) (statement here);

- Greg Fedele, President, Sabreliner Aviation (statement here).

Video of the hearing can be viewed here. The opening statements of subcommittee chairman Roy Blunt (R-MO), full committee ranking member Bill Nelson (D-FL), and subcommittee ranking member Maria Cantwell (D-WA) revolved the around the importance of aviation to the U.S. economy and the need to ensure that airport capacity is sufficient, and that aviation certification is efficient and safe.

Most of the conversation in the first panel revolved around one topic: Passenger Facility Charges (PFCs), the fee airports can impose to their passengers. The federal ceiling on airport PFCs was last raised at the beginning of the century, and currently sits at $4.50 per passenger. Airports have long wanted that limit to be raised or scrapped, with airlines opposing such a move. (Ed. Note: Earlier this month, House T&I ranking member Peter DeFazio (D-OR) introduced a bill allowing PFCs to be increased.)

Overall, Montgomery opposed raising PFCs because that would suppress demand, and he noted that airports have other forms of funding available (namely municipal bonds) that they can use. Hamm-Niebruegge counter-argued that the airlines are only concerned with a few dollars in PFCs but do not seem to care with the myriad of fees that they now impose in their tickets (to be fair, these airline fees are optional – the customer has the option of not paying to check a bag or get a bigger seat, but cannot choose which services at the airport he or she can use to avoid paying the PFC). While it’s true that municipal bonds are an option, many airports are “bonded out” and cannot issue more bonds, and raising the PFC would allow these airports to pay debt quicker and launch new projects.

Hamm-Niebruegge also noted that Airports Council International-North America (ACI-NA) recently estimated that airports will need $100 billion in capital investments in the next five years, and that the available funding tools are not enough to address those needs. Montgomery replied that the $100 billion represents both funded and unfunded projects, and that in fact around 50% of those $100 billion already have funding secured. Montgomery also noted that the report is a sort of a “wish list” of what the airports want, but in reality many of the projects listed have little chance of getting approved even if funding is available.

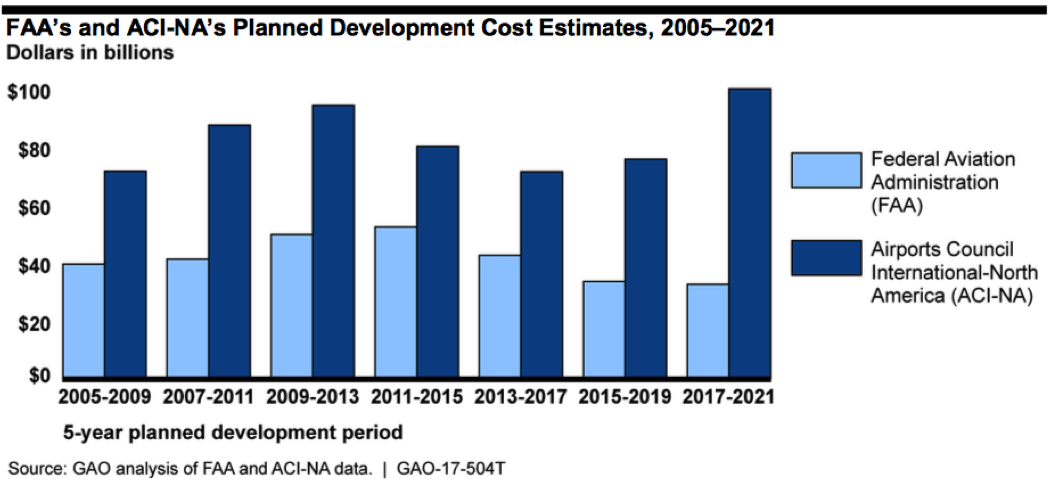

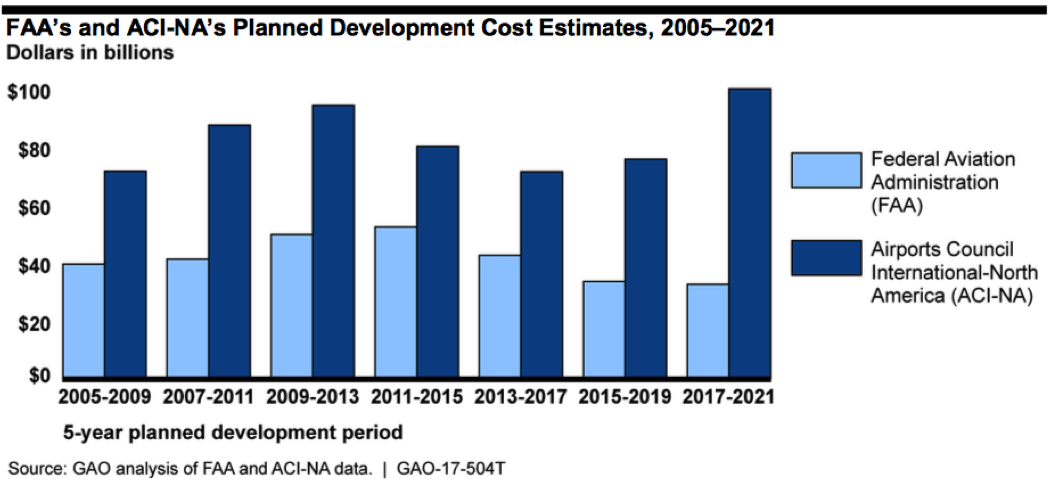

(Also at this hearing, GAO released testimony on the matter of airports’ capital needs, comparing ACI-NA’s projections with the FAA’s, which put the 5-year capital needs at a much smaller $33 billion. Spoiler: the difference mainly comes from the fact that the FAA only includes projects without funding already secured, while ACI-NA includes all projects, funded or not. The FAA has also been pushing airports to only list projects that are truly needed in the next five years – which is what the FAA report is supposed to be about – not all the projects that the airports want to build, regardless of whether they are necessary in the short term or not.)

Besides PFCs, the other topic of interest was brought up by Dan Sullivan (R-AK): the federal permit system. The issue, the senator argued, is that if there is really going to be an infrastructure plan, the federal permit system needs to be modernized to allow projects to be built in realistic time frames. He gave examples, like taking six years to get a permit to build a bridge, or the 15 years it took for Seattle airport to get permit to build a new runway (plus four years of construction). Sullivan said that, according to an airport executive at the airport, those 19 years is more time that it took to build the great pyramids of Egypt.

(Ed. Note: Getting ETW on the fact-checking bandwagon, it appears that the great pyramid of Giza took 20 years to build – according to Herodotus at least, who got the information from a tour guide 2,000 years after the fact, so not exactly a first-hand report – so we are indeed talking about roughly the same timespan, but not exactly “longer than” territory.)

Hamm-Niebruegge replied that the main thing that could be done is to lessen FAA oversight on everything an airport does, as they exert tight control even in areas not related to safety or that do not have any impact on aeronautical uses. Montgomery added that environmental reviews also need streamlining.

In her opening statement of the (considerably shorter) second panel, Gilligan presented a rosy FAA view on certification. She said the FAA is improving certification, delegating more often (90% of certification is done by the companies themselves now), and has developed performance metrics and standards. Still, the FAA needs to be more agile, Gilligan added. (Ed. Note: Eno has been involved in this discussion on how to reform FAA’s certification system through our Aviation Working Group; a report on the matter will come out during this spring.)

Dillingham concurred with the optimistic assessment made by Gilligan, noting that FAA progress in certification is largely a good news story. According to the latest GAO assessment on the matter, FAA has made significant progress in addressing the recommendations made by the committees that were created by the 2012 FAA re-authorization. The FAA is now doing more with its limited resources, translating into fewer delays for the industry, which is an extremely step forward. There are still two areas where improvements are needed, he said. First, FAA must sustain its current levels of commitment to improve the certification processes at the at all levels of the organization. And, related to that, a culture change at the organization, as well as in the industry, is needed for the agency to reap the benefits of some of the changes it has been making.

Fedele, representing a small aviation manufacturer, noted that certification reform will have a positive impact in their business, and as such they support the goals of the trade organization of the industry in moving towards reform. He also touched on the issue of delegation. While his company does not have delegation authority, they contract with one company that does, allowing them to have more predictable certification processes, compared with dealing with FAA directly.

Senators’ questions revolved around two topics: how can the FAA keep with innovation, and what is the agency doing for our international partners to accept FAA-issued certificates in other countries.

On the first topic, the witnesses agreed that the use of risk-based certification, where the FAA focuses its efforts on the more high-risk areas, like new technologies that impact safety, is the way of the future. Fedele argued that the agency must make full use of the delegation authority it has been given. Dillingham added that FAA has gotten much better in making sure they have the right kind of expertise to address new technologies coming online.

Regarding acceptance of FAA-issued certificates by other countries, which allows U.S. products to be sold in those countries much more quickly, the panel noted that the FAA is making progress on that front. That are still some issues in some areas, but overall the situation is much better than in the past.