In August, Eno hosted a webinar titled Congestion Pricing’s Role in Building More Equitable Transportation Systems. The webinar was a follow-up to our report on congestion pricing, which describes ten principles to guide elected officials, civic leaders, advocates, and agency professionals as they develop the policy in their own regions. One of the principles is to “create fair programs.” In other words, equity should be addressed in both the process of developing congestion pricing strategies and in the design of the policy itself.

To dig deeper into the principle of creating fair congestion pricing programs, we hosted a panel of speakers who have long worked on equitable mobility: Tilly Chang, Executive Director of the San Francisco County Transportation Authority; Hana Creger, Environmental Equity Program Manager of the Greenlining Institute; and Río Oxas, Co-founder of RAHOK: Race. Ancestors. Health. Outdoors. and Knowledge.

Here, we want to address some of the outstanding questions we did not have time to raise with our panelists.

How do you define equity with respect to congestion pricing?

In discussions about congestion pricing, equity has been defined in a number of ways: emphasis might be based on income, geographic displacement, or neighborhood exposure to highway pollution.

A common criticism of congestion pricing is that it is a regressive fee that disproportionately affects those who cannot afford to pay. Pricing that does not account for people’s ability to pay or their ability to access multiple modes of transportation can be problematic. However, a number of other aspects of commuting and local trips, and especially car trips, are also regressive by that definition. The price of owning and using a car adds up quickly due to vehicle registration fees, parking charges, gasoline, insurance, and maintenance. Transportation is the second largest expense for most American households, and the working poor tend to spend a larger portion of their income on transportation (especially car transportation) than those in higher income brackets. Low-income individuals rely more on transit, biking, and walking to commute than higher-income individuals, though many low-income individuals purchase cars out of necessity due to insufficient transit or unsafe active transportation options.

Concerns are also often raised that a congestion charge would be unfair to drivers who live outside the congestion pricing zone but must pay the charge to enter the zone for work. However, a number of inequities, like subsidies for parking facilities, have led to market distortions enabling urban sprawl.

Congestion can also result in inequitable health outcomes for those who live near highways, in particular predominately nonwhite communities, which are more likely to be exposed to highway pollution than predominately white communities. Highway pollution contributes to a number of respiratory issues like asthma, chronic pulmonary disease, chronic bronchitis, decreased lung function, and a weakened immune system.

What are some best practices for effectively identifying and reaching disadvantaged groups in the process of designing a congestion pricing policy, and how can decision-makers measure equitable participation

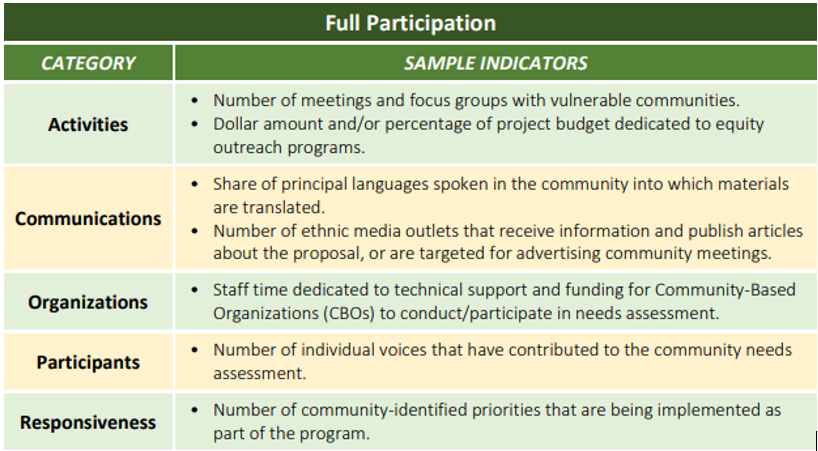

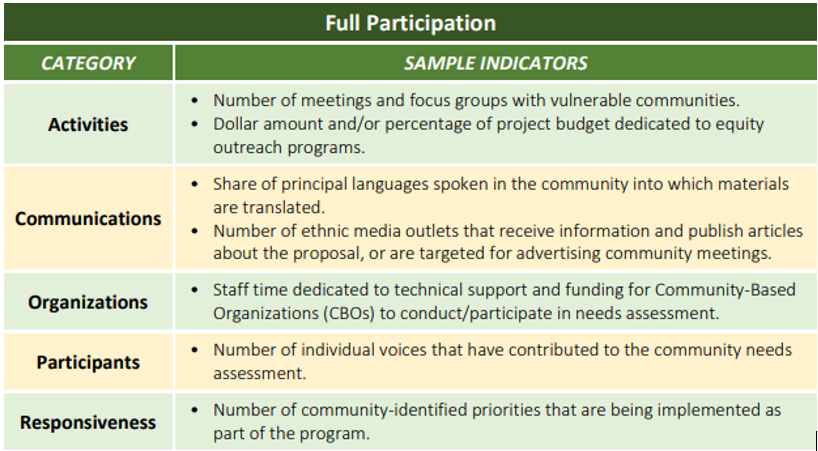

Participation of vulnerable communities in the planning of a congestion pricing policy can take a number of forms, but a higher degree of participation looks like community groups partnering closely with planning agencies through advisory groups or participatory decision-making. Ideally, community representatives will have a seat at the decision-making table through citizen juries, formal representation, or voting representation. A 2019 report listed the following sample indicators to measure full participation:

Continued outreach with the identified communities through the development of the policy and after implementation will also result in a more equitable process. Project planners must be ready to evaluate whether the program outcomes align with pre-determined mobility equity indicators, and to clearly communicate these results with affected communities.

How can congestion pricing not only “do no harm” but also actually create a more equitable transport system that overcomes some of the inequities identified in the presentation?

Congestion pricing can be a powerful tool to address systemic transportation inequities if the system is designed to allocate revenues to projects that don’t contribute to automobile dependency, sprawl, and air pollution, outcomes that disproportionately burden vulnerable communities. Pricing auto travel can result in fewer cars on the road, thus mitigating congestion and improving health and safety outcomes. When coupled with other benefits, like reduced transit fares and incentives for shared options, non-single occupancy vehicle options become more attractive.

While there may be temptation to offer exemptions for certain groups, this approach may not be effective if too many exemptions are offered, thus counteracting the intended outcome of less traffic congestion as was the case in Stockholm. Discounts may be an appropriate approach for low-income drivers who must rely on automobiles, but providing robust alternatives is critical to reducing congestion.