Guest op-ed by George Soodoo, former chief of the Vehicle Dynamics Division at the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, Office of Crash Avoidance Standards.

Rulemaking is the process by which Federal agencies develop, amend, or rescind regulations. It is often likened to sausage making – the process is messy, but the product is tremendous.

The rulemaking process is generally adversarial, contentious, and time-consuming. However, over the past five decades, the rulemaking process has produced regulations that have resulted in substantial and admirable gains in transportation safety across all modes, with significant reductions in crashes accidents and fatalities.

In particular, motor vehicle safety regulations have played a major role in making automobile travel increasingly safe for the American public. Regulations for seat belts, airbags, and electronic stability control, among many others, have helped to significantly decrease fatalities from a peak of over 50,000 in 1980 to about 33,000 in 2014, before rising to 40,200 in 2016. By any measure, this is tremendous progress for motor vehicle safety.

So, let’s take a closer look at how the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) conducts rulemaking to achieve these safety gains.

NHTSA is the agency responsible for motor vehicle safety within the U. S. Department of Transportation. The agency has Congressional authority to establish Federal motor vehicle safety standards (FMVSS) for all new motor vehicles and equipment sold in the U.S. NHTSA initiates rulemaking action to address a safety problem by one of several means: Congressional mandate; petition for rulemaking from industry or the public; or NHTSA’s own initiative for standards maintenance or international harmonization.

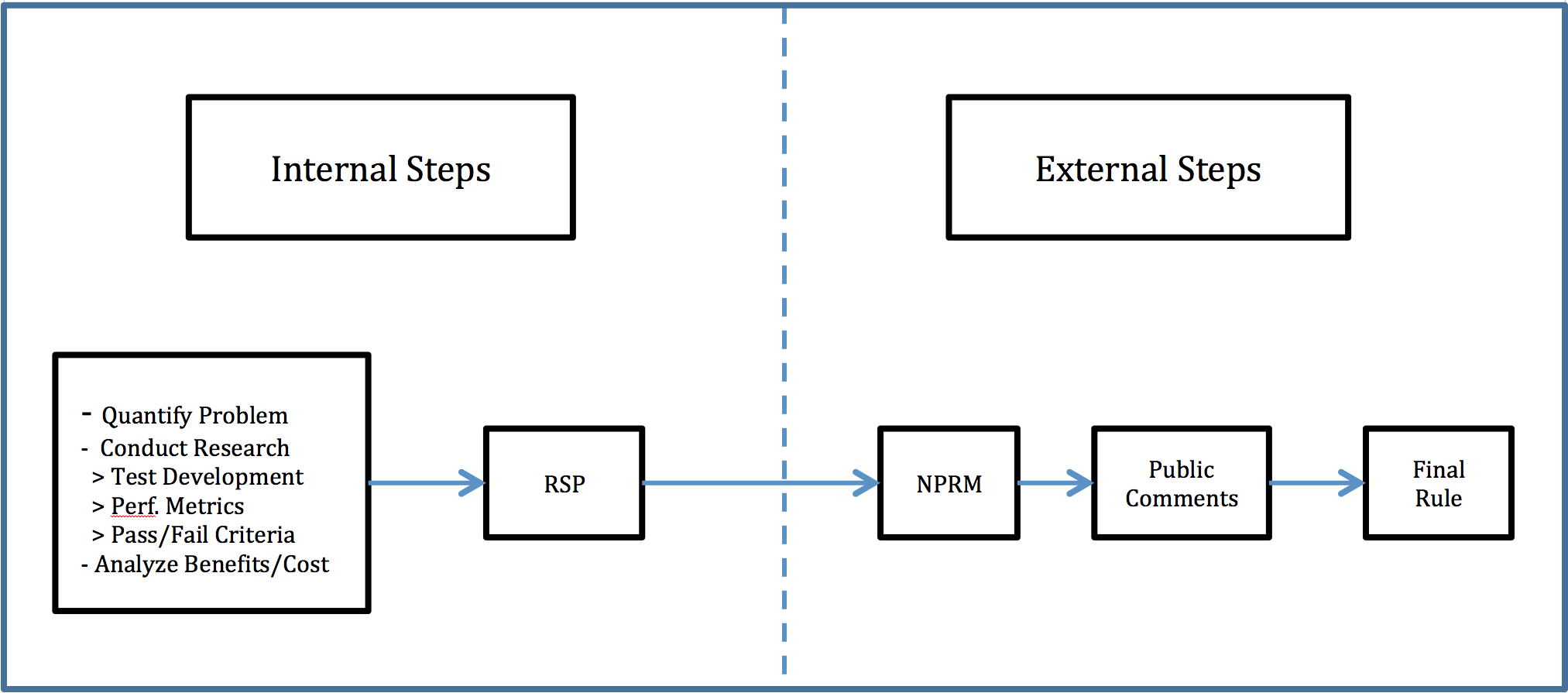

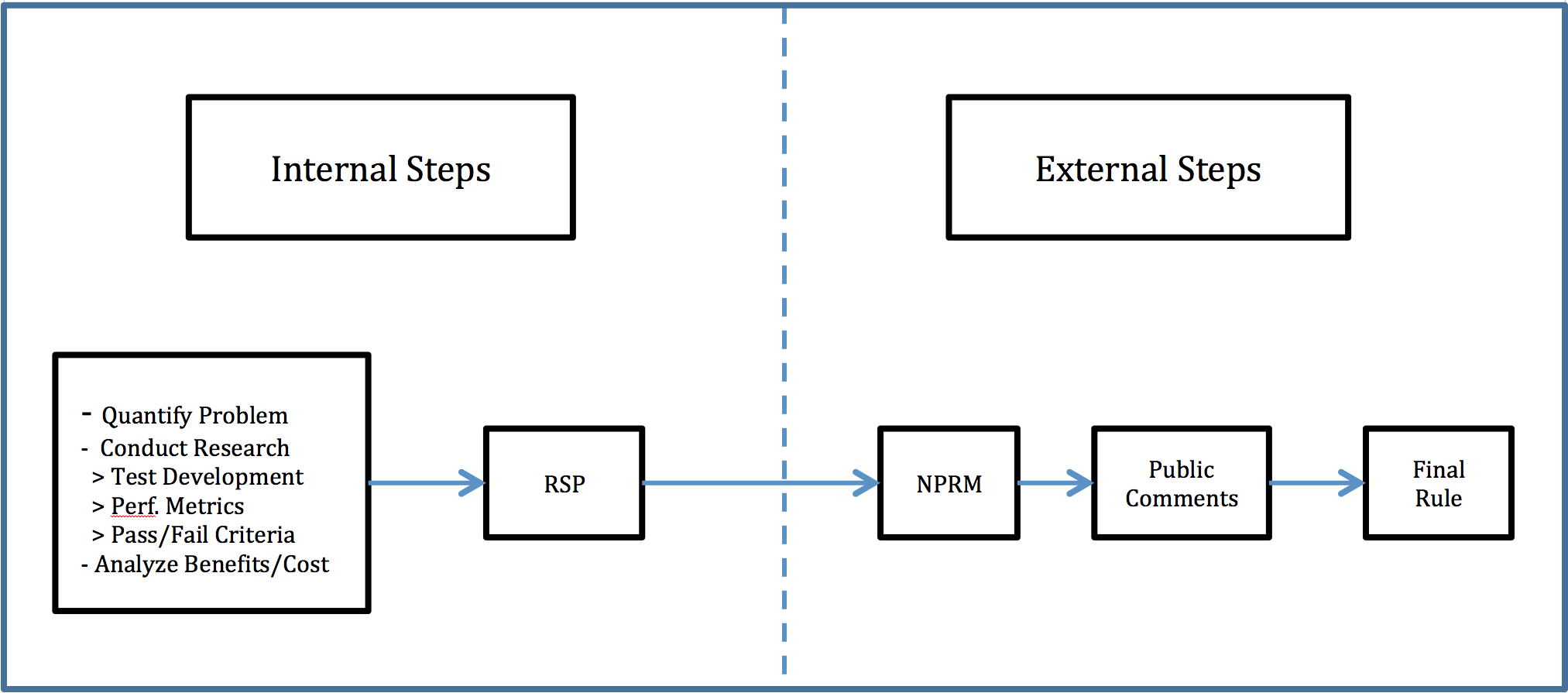

The rulemaking process at NHTSA may be viewed as a two-step process that involves internal and external actions. The internal actions center on synthesizing various elements of the agency’s work into a coherent document called the rulemaking support paper (RSP), which is used to draft the external document published as the notice of proposed rulemaking (NPRM) in the Federal Register. The external actions are dictated by the Administrative Procedures Act (APA), which governs how a Federal agency conducts rulemaking. The APA requires that an agency: 1) publish in the Federal Register an NPRM that provides details about its proposal; 2) give the public an opportunity to comment on the proposal; and 3) publish the final rule. On average, it takes about 5 years to complete rulemaking on an issue of medium complexity.

Internally, the agency’s first step is to quantify the safety problem by analyzing police-reported fatal and non-fatal crashes in its databases. The agency may also use information from industry stakeholders, consumer complaints, and insurance companies to assist in this task.

NHTSA then conducts research using systems designed to address the safety problem. This research focuses on:

- developing one or more tests to evaluate the performance of the systems;

- determining the metrics that would be most effective at evaluating their performance; and

- determining the pass/fail criteria that would achieve the desired safety benefits.

The agency also develops a benefits and cost analysis to ensure that the safety benefits achieved by the new requirement outweigh the resulting cost to consumers. This analysis is reported as a preliminary regulatory impact analysis (PRIA), which is submitted to the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) for review and approval before the NPRM is published.

The external part of the rulemaking process begins with the publication of the NPRM in the Federal Register. A typical NPRM includes the following sections: 1) preamble that provides a narrative explaining the proposal; 2) benefits and cost analysis; 3) regulatory text that includes vehicle applicability, performance requirements, test procedure, and pass/fail criteria; and 4) mandatory effective date when the regulated parties must comply with the new regulation. The NPRM provides a specific comment period, typically 60 or 90 days, and solicits comments from the public. Comments are placed in a docket that is fully accessible to the public at www.regulations.gov.

If the agency is unable to issue an NPRM because critical pieces of information are lacking, such as incomplete vehicle research that prevents the agency from determining performance metrics, the agency may issue an advance notice of proposed rulemaking (ANPRM) or a request for comments (RFC) notice to seek this information from the public. These notices focus on asking questions, the answers to which could help the agency develop an NPRM. The ANPRM starts the rulemaking process and requires that a termination notice be published if the agency decides to not continue the rulemaking process, whereas the RFC does not start the rulemaking process or require a termination notice if no further action is taken. Regardless of whether the agency chooses to use an ANPRM or an RFC, an NPRM must be issued as the next step if the agency decides to proceed with rulemaking action.

Once the comment period closes, the agency reviews all the comments in the docket. The comments that get the most attention are those that provide empirical evidence to support the commenter’s position. Comments that state an opinion without any supporting evidence are reviewed but generally have little impact on the agency’s decision for the final rule.

For the final rule, NHTSA goes through an internal process similar to the one for the NPRM. Commenters often submit data to challenge some aspect of the NPRM, such as the proposed pass/fail criteria, and this may persuade the agency to change the proposal to make it less stringent for the final rule. The proposal cannot be changed to make it more stringent for the final rule unless the public is given the opportunity to comment before the final rule is issued. If the agency wants to increase the stringency of the proposal, it must issue a supplemental notice of proposed rulemaking (SNPRM) or a new NPRM to include the more stringent portions.

The agency prepares a final regulatory impact analysis (FRIA) on the benefits and cost revised accordingly to reflect any changes for the final rule. Once OMB approves the FRIA, the agency can publish the final rule. The mandatory effective date of the rule is the date on or after which all newly manufactured vehicles or equipment for sale in the U.S. and to which the regulation applies must comply with the new requirements. The flow chart below provides a summary of the rulemaking process at NHTSA.

Rulemaking Process

Following the publication of the final rule in the Federal Register, there is a 45-day period during which the public may submit petitions for reconsideration to change the final rule. Such petitions must be within the scope of the NPRM or the final rule and must have supporting evidence that makes a case for the change the petitioner requests. If the agency accepts the petition, it is required to respond by issuing a Final Rule-Response to petition for reconsideration in the Federal Register.

The Federal rulemaking process is transparent and open, and encourages public participation. It includes several internal and external steps that lead to the publication of a final rule. Even though the process can be adversarial, contentious, and time-consuming, these steps allow Federal regulators to establish motor vehicle regulations where the safety benefits are irrefutably life-saving for the American public.

George Soodoo is the former chief of the Vehicle Dynamics Division at the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, Office of Crash Avoidance Standards.