In his 1987 history of the Federal Reserve, Secrets of the Temple, journalist William Greider told a funny story illustrating the Fed’s history of situational claims as to whether it is a public institution or a private one. In 1935, the Fed wrote a check to the U.S. Treasury for $750,000 to purchase some prime real estate on Constitution Avenue in Washington, D.C. Treasury signed over a deed giving up “all the right title and interest of the United States” to that land, where the Fed built a headquarters building in 1937.

Since the 12 Federal Reserve Banks are owned by their (private, for-profit) member banks, the District of Columbia tried to get the Fed to pay annual property taxes on the headquarters building. The Fed refused to pay, saying that they were still a part of the federal government, even though they were owned by private industry. The District responded by asking, essentially, “if you are part of the federal government, why did you have to buy land from them?” and kept trying to collect taxes.

In December 1941, the District went so far as to file the paperwork to seize the Fed’s headquarters building and sell it at auction to pay the back property taxes. World War II postponed the auction, and eventually, Greider wrote that the 12 Fed Banks had to sign a quitclaim deed transferring the property title back to the federal government to end the tax problem.

In the transportation field, we also have an entity that claims, at various times, to be public or private, whichever suits the moment. That would be Amtrak, which was chartered by a 1970 law as “a for profit corporation…not an agency or establishment of the United States Government.” That wording has since changed, and today’s statute says that Amtrak “shall be operated and managed as a for-profit corporation; and is not a department, agency, or instrumentality of the United States Government.”

But that private, non-government company received over $50 billion in federal subsidies in the 1970-2020 period. And last fall’s bipartisan infrastructure law gave Amtrak an additional $22 billion in guaranteed funding, plus the inside track to compete for tens of billions in additional funding in competitive rail grants, plus Amtrak’s usual annual subsidy of $1 to $2 billion per year.

Regardless of the statute, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1995 that Amtrak “is part of the Government for purposes of the First Amendment,” and ruled again in 2015 that “Amtrak is a governmental entity, not a private one, for purposes of determining” whether or not Amtrak could jointly exercise regulatory power with the Department of Transportation.

Both of those Court opinions hinged on the fact that almost the entirety of Amtrak’s Board of Directors is nominated by the President and confirmed by the Senate. The Senate Commerce, Science and Transportation Committee is holding a hearing tomorrow on President Biden’s five nominees for the Amtrak Board, which provides the committee’s members an opportunity to get some clarity about Amtrak’s status.

Compensation. Last month, the New York Times used the Freedom of Information Act (which applies to Amtrak only in years Amtrak receives a federal subsidy, which is every year) to uncover millions of dollars in cash bonuses being given to senior Amtrak employees over the last five years (including while receiving massive federal COVID aid). But the Times also reported that “Amtrak declined to provide a fuller picture of how its executives are compensated, including salaries.”

If Amtrak were truly a private company (publicly traded), the compensation of its senior executives would be revealed in its SEC filings. And if Amtrak were truly a part of government, its executive compensation would be a matter of public record, since they would be taxpayer employees. But because Amtrak is partly in and partly out of government, not even the New York Times can ascertain how much its executives get paid (and paid with, in large part, federal tax dollars).

We don’t know how much the total compensation packages are. But the article indicates the senior Amtrak executives probably made more than the CEO of the New York City Metropolitan Transportation Authority, who makes $350 thousand a year (no bonus). The MTA carries three times as many passenger-miles each year than Amtrak and has almost four times Amtrak’s budget. But the MTA is explicitly a part of state government, and most other mass transit agencies in the country also cap their CEO compensation in the ballpark of the MTA’s chief.

Do the Amtrak Board nominees believe that Amtrak executive compensation should be a matter of public record, and do they think Amtrak should pay like a for-profit freight railroad, or like a taxpayer-supported provider of passenger transportation?

Open Meetings. The infrastructure law provided $22 billion in advance appropriations for Amtrak, with very little oversight or transparency. In particular, Amtrak’s ability to pretend that it is a private company, and not a “Government corporation,” allows it to continue to evade the federal Open Meetings Act, which requires every other federal board and corporation to hold open meetings and to make public the minutes of its meetings.

Everyone else, from the Fed and the Postal Service Board of Governors to the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and the FDIC, has to hold regular, open meetings and release many of the agendas and minutes of any closed meetings after some time has elapsed. But Amtrak has never done so, and unless things change, they will get to decide how they spend their $22 billion in infrastructure law appropriations completely behind closed doors.

Do the Amtrak Board nominees believe that some sunshine in Amtrak Board meetings would be useful, or do they intend to continue to conduct all Amtrak business behind closed doors?

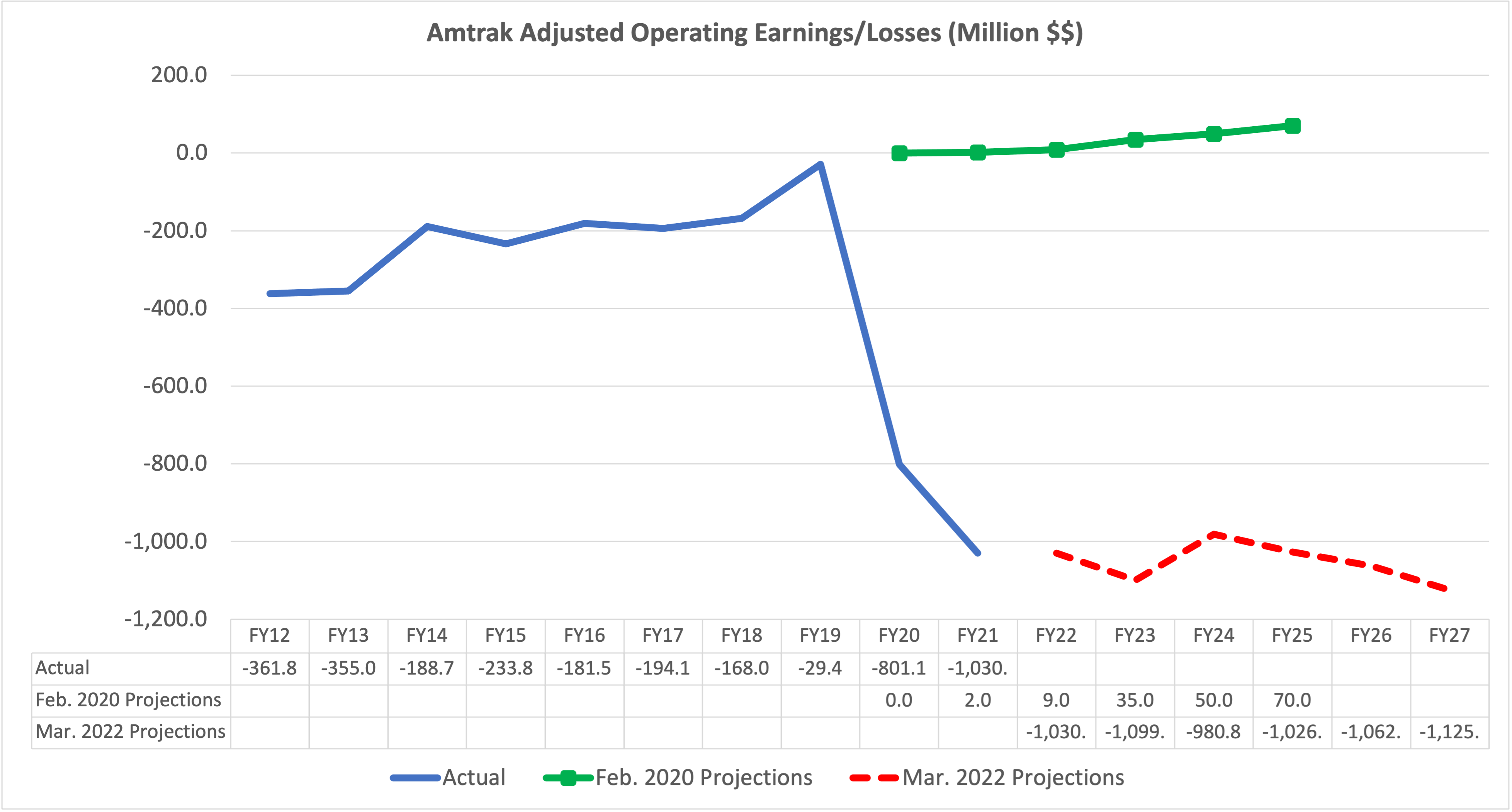

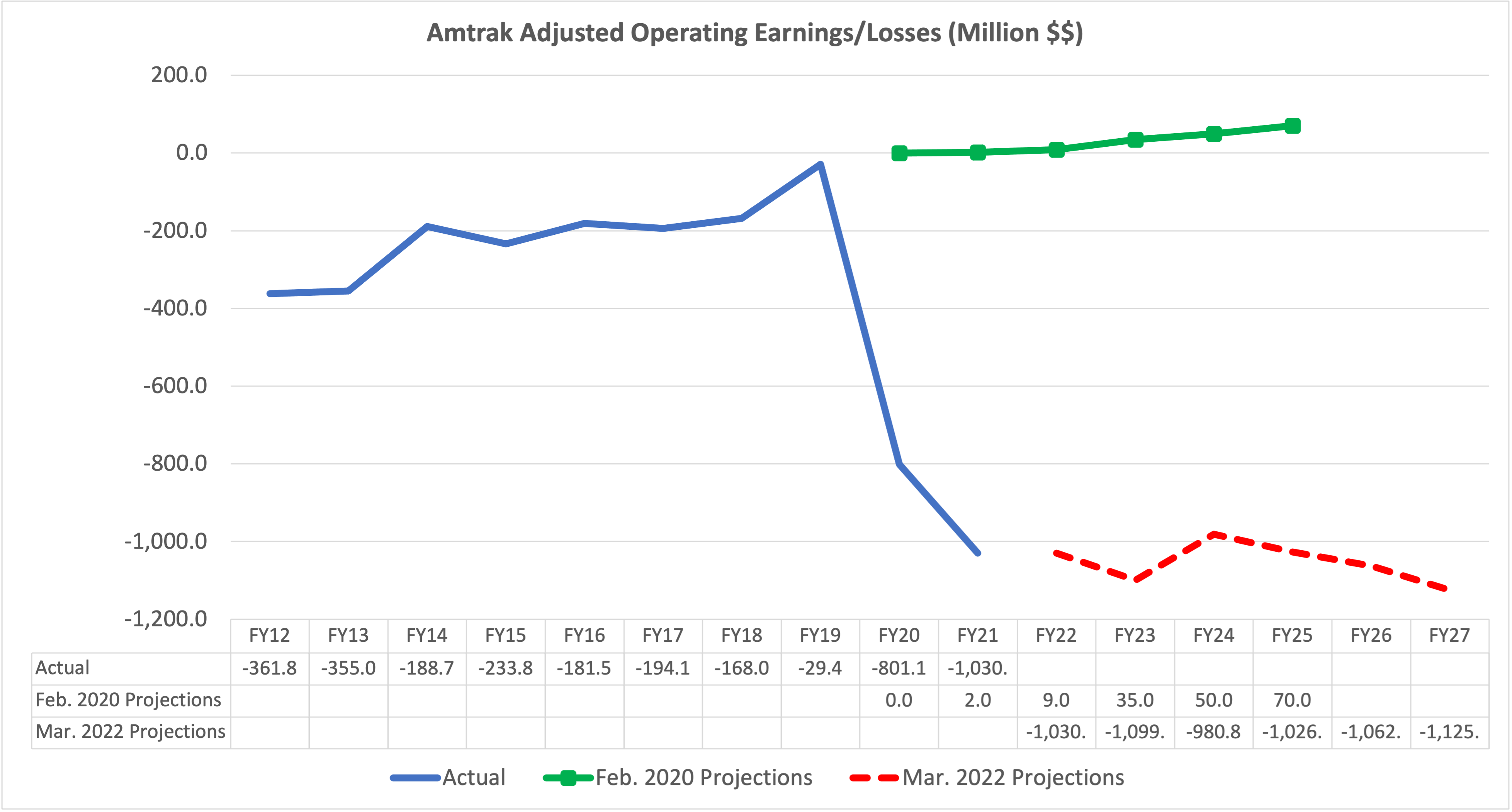

Operating losses. After decades of hectoring by Congress to run its operations in a more business-like manner, Amtrak in 2019 came tantalizingly close to breaking even on the operations side, with adjusted operating earnings falling just $29 million short of total revenue. And they were on track for “the first break-even year in the company’s history” in 2020, until COVID hit.

As detailed in ETW four months ago, Amtrak now projects that its ridership will return to pre-COVID levels by 2024. But instead of ever getting back to operational break-even, Amtrak’s latest budget calls for $1 billion per year adjusted operating losses every year through at least 2027, with no signs of ever getting close to operational break-even again.

During the Senate debate on the infrastructure bill, there was no discussion of turning Amtrak back into a perpetual ward of the state, or of perpetual billion-dollar annual operating losses being part of the Sinema-Portman-Manchin-Romney plan. Nevertheless, that appears to be the result.

Do the Amtrak Board nominees believe that Amtrak should even aspire to operate without the need for federal operational subsidies? Do they believe that operational break-even is still possible (as it was pre-COVID)? Or are they willing to endorse billion-dollar-per-year federal operating subsidies, in perpetuity, as the current Amtrak Board has done in its most recent budget plan?

If anyone bothers to ask questions like these, the answers could be illuminating.

The opinions expressed above are solely those of the author and do not express the views of the Eno Center for Transportation.