December 16, 2016

Even as the Obama Administration prepares to close up shop next month, the U.S. Department of Transportation is continuing its mission to drive innovation in the transportation sector with globally unprecedented actions.

This week, the National Highway and Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) released a long-awaited proposed rule on connected vehicles (CVs), which it predicts could eliminate or reduce the severity of up to 80 percent of non-impaired crashes.

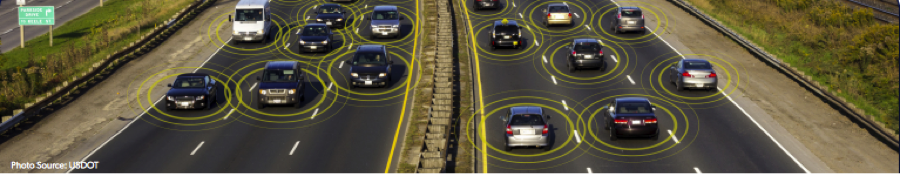

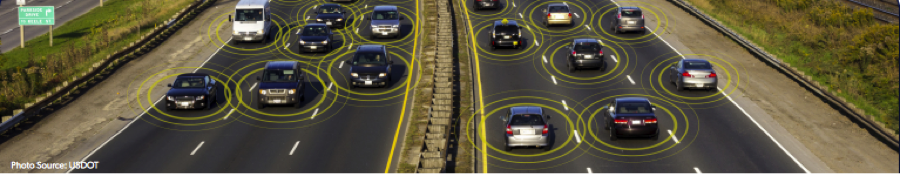

The proposed rule would require all light-duty vehicles manufactured after 2023 to be outfitted with digital short-range radio communications (DSRC) technology, which allows vehicles to communicate basic safety and traffic information to other vehicles (V2V) and infrastructure (V2I).

In essence, a CV sends out a constant stream of information to other vehicles that includes its speed, direction, braking, steering, and path predictions. In turn, other vehicles analyze this information to predict potential hazards and warn the driver of imminent collisions. It is, more or less, a series of instantaneous game theory calculations conducted by on-board computers.

Once fully deployed, NHTSA projects that 400,000-600,000 crashes per year can be avoided – resulting in 190,000-270,000 fewer injuries and saving 780-1,800 lives annually.

To this end, NHTSA identified 6 safety-critical functions that manufacturers can implement by utilizing CV technology:

- Intersection Movement Assist: warns the driver when it is not safe to enter an intersection when there is a high probability of colliding with other vehicles (e.g. a car accelerating through a yellow light)

- Left Turn Assist: warns the driver when there is a high chance of colliding with oncoming vehicles when making a left turn (often unprotected). This is most applicable when a vehicle making a left turn from the opposite direction blocks the driver’s view of oncoming traffic.

- Emergency Electronic Brake Light: mostly applicable in poor weather conditions or peak traffic periods, the car warns the driver of sudden slowdowns or stops of other CVs traveling in the same direction.

- Forward Collision Warning: alerts the driver of an imminent rear-end collision with a vehicle directly in front of it that is traveling in the same direction.

- Blind Spot Warning and Lane Change Warning: detects and warns the driver of vehicles in its blind spot (or coming into its blind spot) before a lane change.

- Do Not Pass Warning: calculates the speed of traffic moving in both the same and opposite directions in order to warn the driver when it is unsafe to pass a slower-moving vehicle in its lane.

(Source: USDOT)

Better Late Than Never(?)

The 400 page long proposed rule has been in the making since 1999, when the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) set aside a portion of the 5.9GHz spectrum band for the anticipated development of vehicle connectivity technologies.

This has drawn considerable ire from wireless carriers in recent years, which have lobbied the FCC to allocate a portion of the band to them. Automakers like Toyota argue that this could cause a portion of the spectrum to become crowded and create a public safety hazard. (Ed. note: This issue has yet to be resolved and goes further into the weeds, well beyond the scope of purely transportation implications and into technical telecommunications issues)

While the technology has been mature enough for deployment for much of the past 17 years since the spectrum was allotted, uncertainty over who will prevail in this lobbying effort has, at least in part, foiled automakers’ plans for the development and deployment of this technology.

The second component of the slowdown has been the failure of NHTSA to issue a uniform set of standards for automakers to follow in order to ensure compatibility of V2V devices.

While the agency took a pragmatic approach in deferring to the auto industry on communications and cybersecurity standards for the devices, the regulatory uncertainty was viewed as much too burdensome for the industry. The fear was that the technology would be undercut – or simply outdated – by future actions by the agency.

This is an issue of compatibility: in order for V2V and V2I technology to deliver on its promises, manufacturers needed to be certain that all vehicles and smart infrastructure would be able to speak to one another in a common language. In other words, a Toyota Prius must be designed to also communicate with a Ford Fusion to prevent a collision – there would be no point in deploying life-saving technologies that could not actually save lives.

On a public spending level, there exists another moral hazard: if cities invest in smart infrastructure, they should not be subject to the burdens of planned obsolescence. Without standards in place, manufacturers of vehicles and smart infrastructure could make each generation of products incompatible by using different communications protocols – leaving the city on the hook for replacing outdated infrastructure.

Convincing the Public

Despite the potential safety benefits, connected vehicles present a familiar set of privacy and cybersecurity concerns.

For each node that is added to a network, there is a new set of vulnerabilities. Deploying hundreds of thousands, and eventually millions, of vehicles that are connected to a single communications network creates a slew of vulnerabilities.

This October, an unprecedented cybersecurity attack affected 80 major websites – an attack mounted by hackers who had taken over an army of devices that are part of the “internet of things” (IoT), the ecosystem of mobile devices, tablets, cameras, home appliances, and other items that are capable of connecting to the Internet.

While the attack had the limited result of bringing down sites like Twitter, Netflix, CNN, and the Guardian, a similar widespread hack of vehicles would have chilling implications.

In addition to the tangible risks, another concern for consumers will be data security. The constant communication between CVs means that data will be widely dispersed, and therefore must be encrypted in order to avoid a consumer’s privacy being compromised – allowing nefarious users to collect information and deduce an individual’s home address, work address, and so on.

Connected and Autonomous

While this technology has been developed at the same time as autonomous vehicles (AVs), it is important to note that they are not necessarily the same thing. A connected vehicle is simply a vehicle that can communicate with other vehicles and (at this stage) warn the driver of hazards, while an autonomous vehicle is capable of driving itself with limited or no external input.

At the same time, these technologies are not mutually exclusive. AVs already use a series of radar, cameras, and laser sensors to collect information about the world around them. Each of those components have their own weaknesses based on weather conditions, visibility, and other factors.

The effectiveness of DSRC, however, is not diminished in poor weather conditions and can “see through” other vehicles and obstacles – potentially addressing some weaknesses of autonomous vehicles.

Traffic safety advocates have suggested that combining automated and connected functions would yield even greater benefits by allowing the vehicle to detect and respond to hazards with minimal delay.

As an early example, the fatal collision between a semi-automated Tesla and a tractor-trailer this July when the Tesla’s sensors failed to detect the tractor-trailer, mistaking it for a bright sky instead. Some experts suggest that, if the Tesla and tractor-trailer were both equipped with V2V technology, the collision may have been avoided.

However, it must be noted that this NPRM only applies to light-duty vehicles. A proposed rule on trucks has yet to be produced, signaling that there is much more work to be done.

Comments on the proposed rule, which would implement new Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standard (FMVSS) No. 150, must be submitted within 90 days of publication.

Additional resources provided by NHTSA

- Fact sheets:

- Videos available for download and broadcast