At its November 30 Board of Directors meeting, the New York City Metropolitan Transportation Authority gave a budget update and a new proposed financial plan for the upcoming year that gives us an update on the status of the “fiscal cliff” that the MTA and other major transit providers will be facing, to some extent, in the next few years.

Ridership

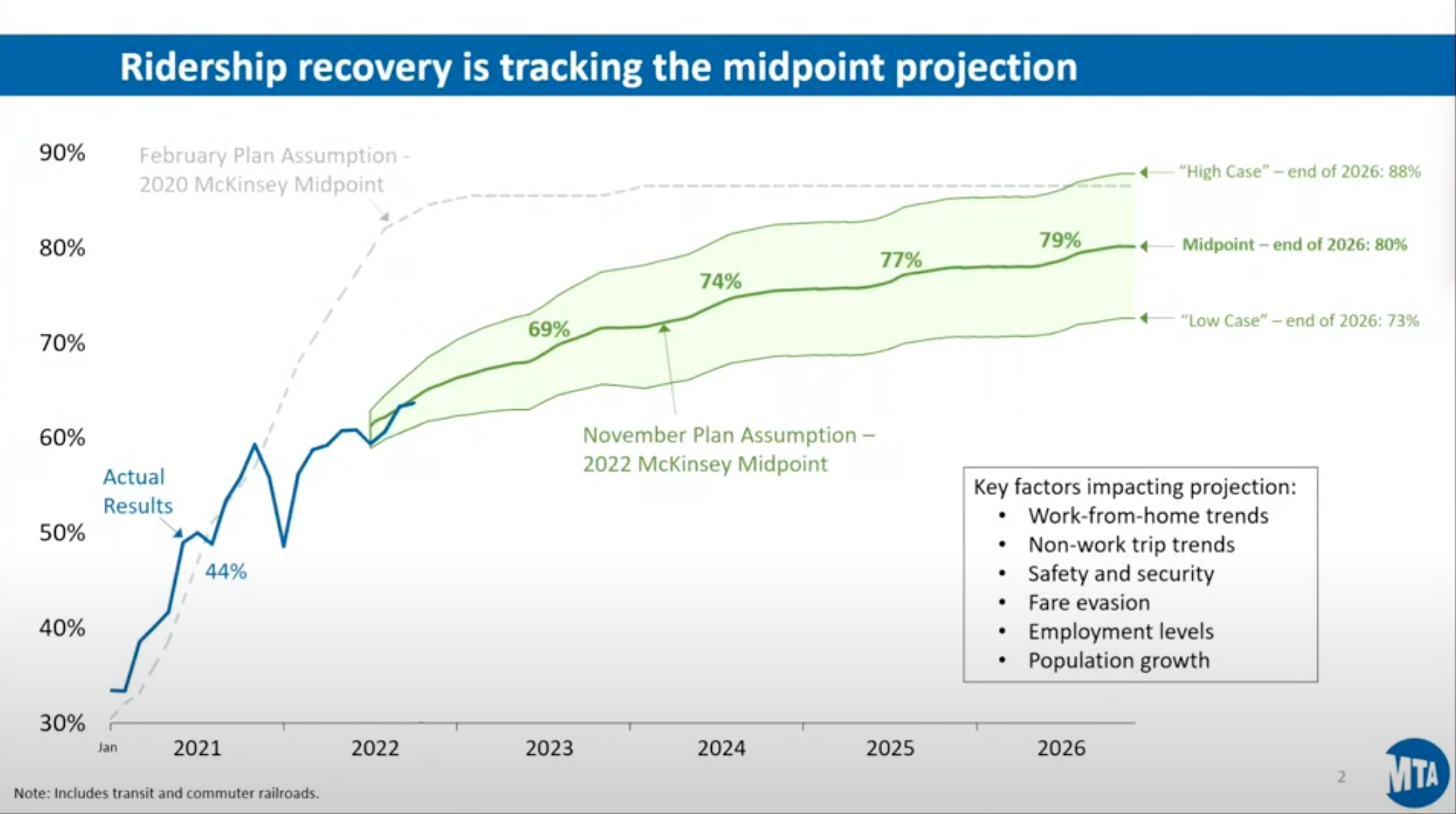

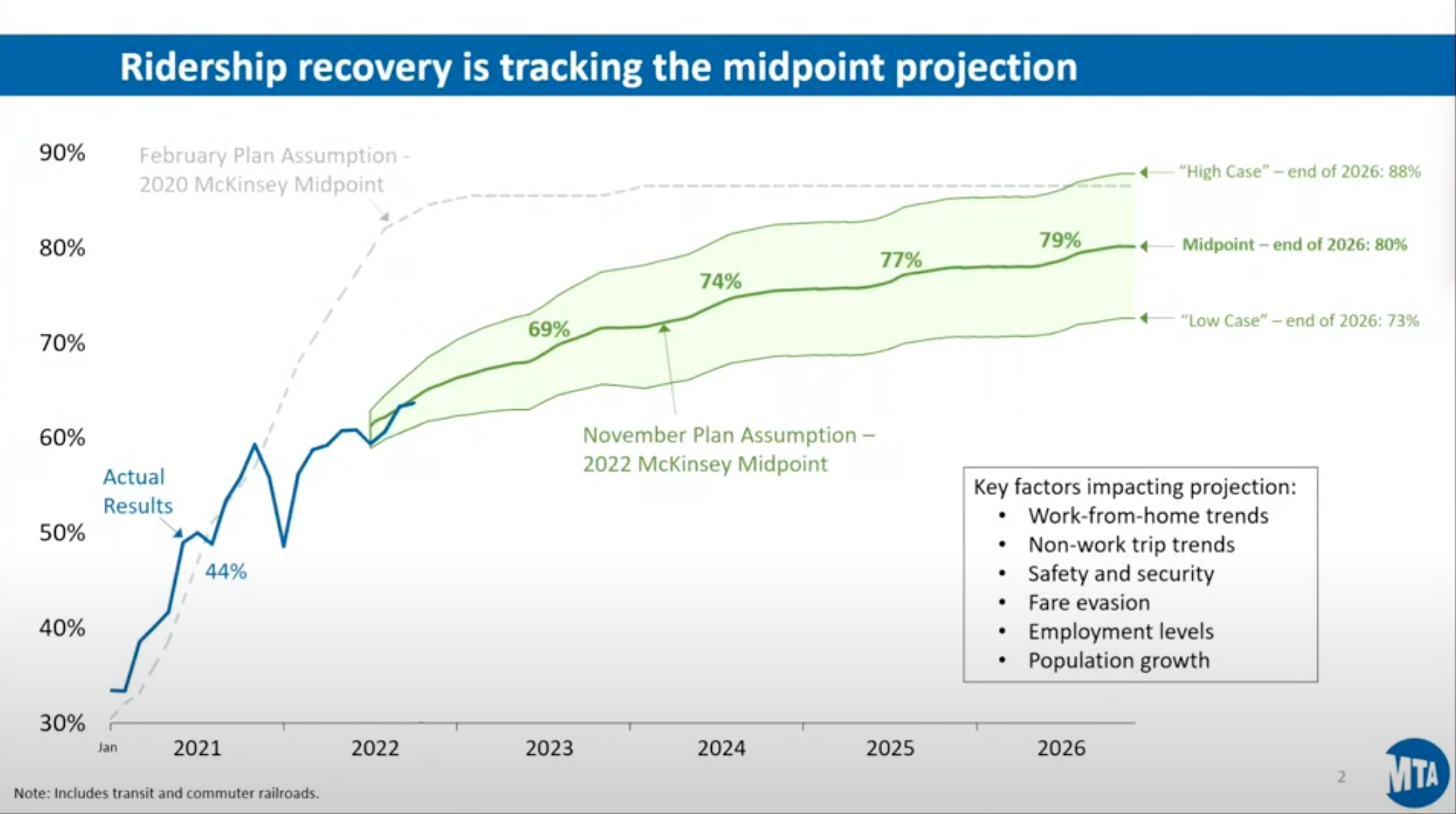

In terms of ridership, the MTA hired McKinsey to do post-COVID ridership forecasts. Twice. The midrange estimate of the original McKinsey forecast, from 2020, predicted that ridership would be back above 80 percent of the pre-COVID levels by now and would get up to an 85 percent “new normal” by the end of 2023. They were actually on track with the midrange estimate of the 2020 McKinsey forecast until the COVID Delta Omicron variant caused a retreat in ridership in mid-2021.

So the MTA got a new McKinsey forecast earlier this year, and so far, they are on track for the midrange estimate of that forecast. But right now, that is just above 60 percent of pre-COVID ridership, and the projection only gets to 69 percent in 2023, 74 percent in 2024, and only gets to 80 percent at the end of 2026.

Fare revenues

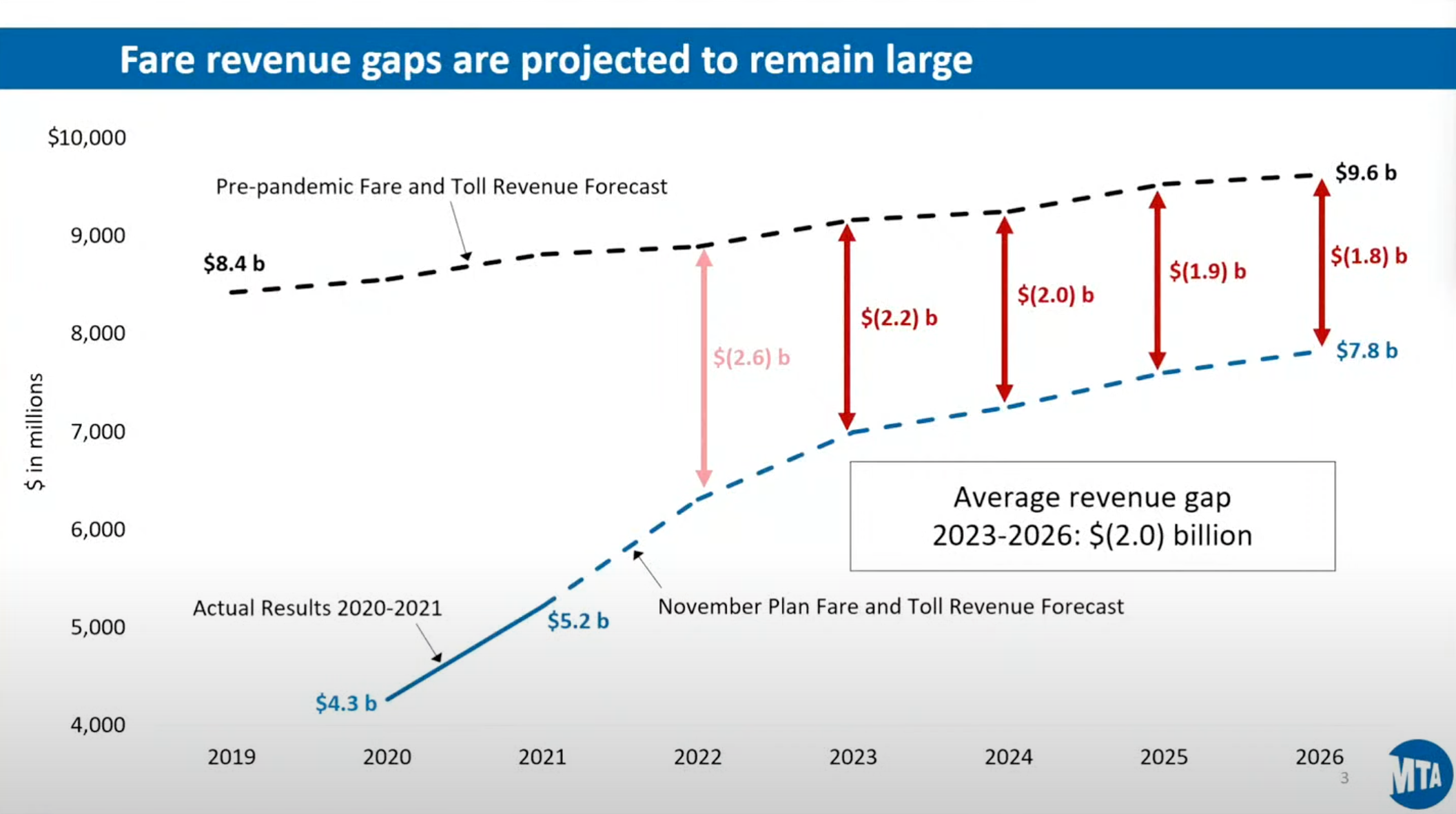

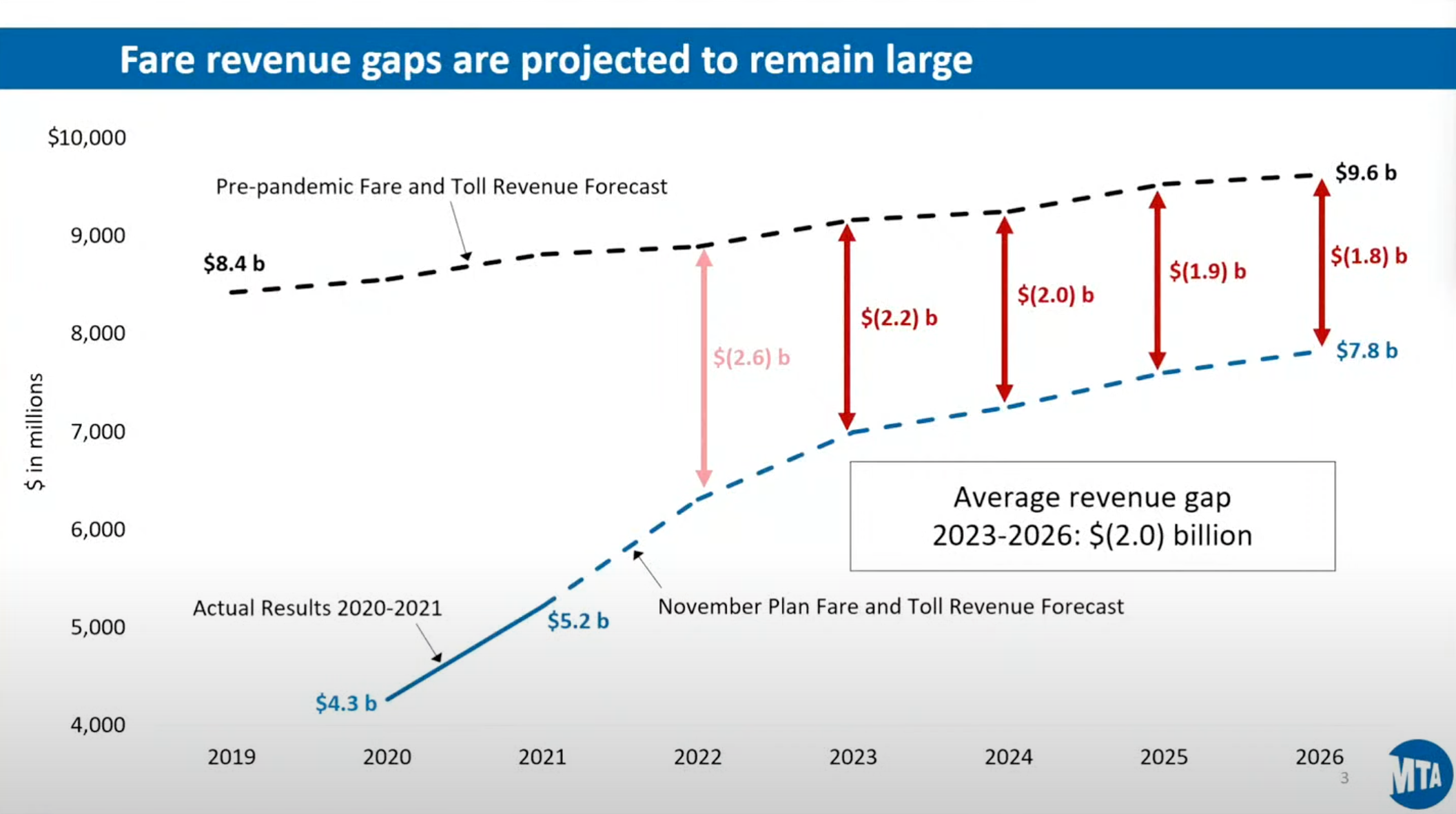

When riders vanish, so do the fares they had been paying on a daily basis. The MTA has an advantage over many other systems in that the MTA doesn’t just get fare revenues, they also get toll revenues from local bridges and tunnels. This also took a big hit from COVID but was much quicker to rebound.

COVID cut combined farebox and toll revenue in half in 2020, from a projected $8.6 billion to $4.3 billion. (The MTA uses calendar year (January 1) budgeting, which distinguishes themselves from New York City, which uses a a July 1 fiscal year; New York State, which uses an April 1 fiscal year; and the federal government, which uses an October 1 fiscal year.)

This has dropped to what they now estimate will be $2.6 billion below pre-COVID estimates in the ongoing calendar year 2022. The ridership forecasts in the previous slide indicate an average revenue gap of around $2 billion per year through 2026.

The specific numbers (from the November 2022 financial plan, Book 1, page II-2) are like so:

|

|

Actual |

Actual |

Actual |

Tentative |

Budget |

Forecast |

Forecast |

Forecast |

| Million $$ |

CY 2019 |

CY 2020 |

CY 2021 |

CY 2022 |

CY 2023 |

CY 2024 |

CY 2025 |

CY 2026 |

|

Farebox Rev. |

6,351 |

2,625 |

3,048 |

3,989 |

4,513 |

4,653 |

4,773 |

4,913 |

|

Toll Rev. |

2,071 |

1,640 |

2,170 |

2,323 |

2,323 |

2,332 |

2,335 |

2,338 |

|

Total F&T Rev. |

8,422 |

4,265 |

5,218 |

6,312 |

6,836 |

6,985 |

7,108 |

7,251 |

| Percent Change |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Farebox Rev. |

|

-59% |

+16% |

+31% |

+13% |

+3% |

+3% |

+3% |

|

Toll Rev. |

|

-21% |

+32% |

+7% |

+0% |

+0% |

+0% |

+0% |

|

Total F&T Rev. |

|

-49% |

+22% |

+21% |

+8% |

+2% |

+2% |

+2% |

Effect on budgets

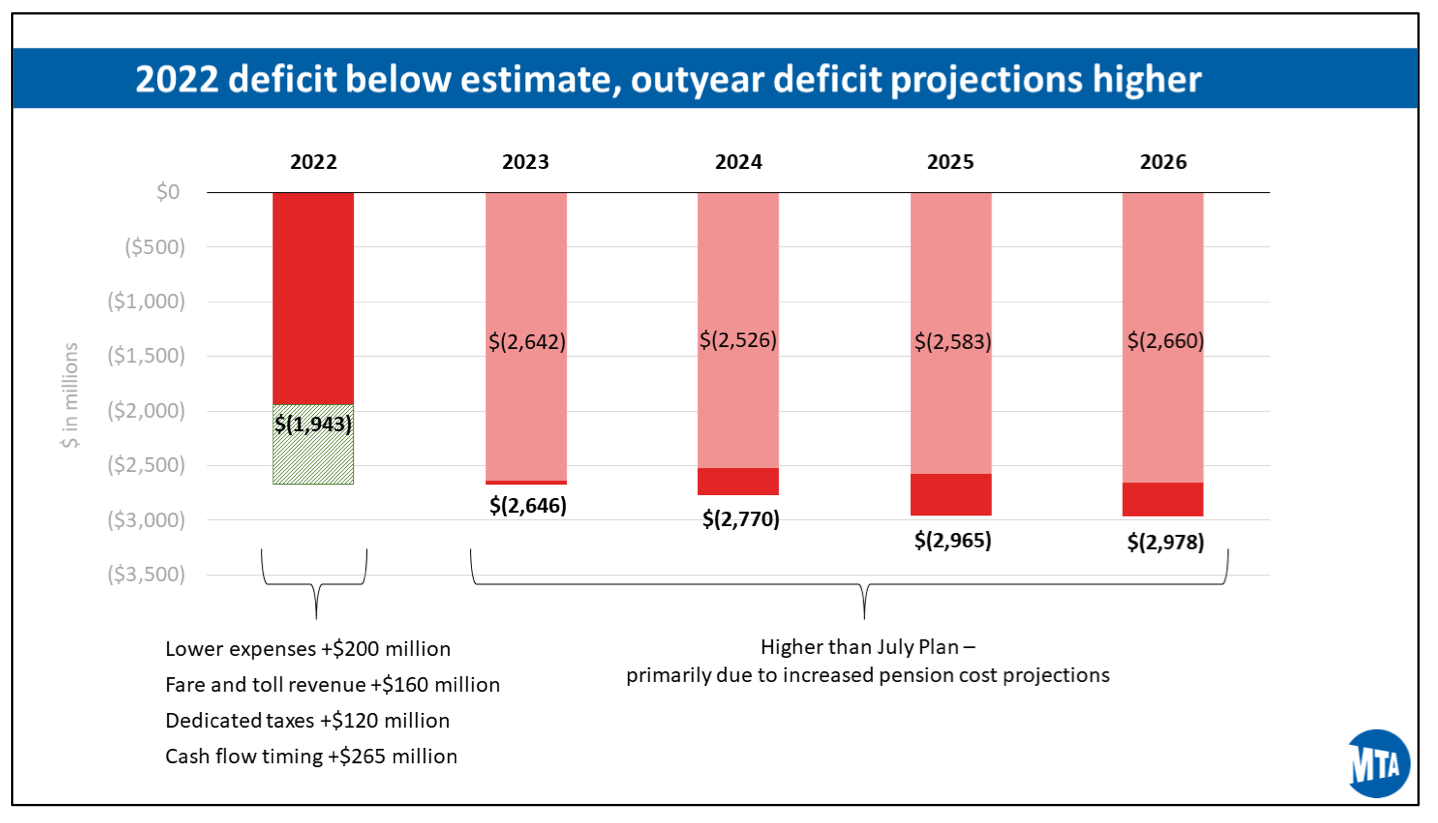

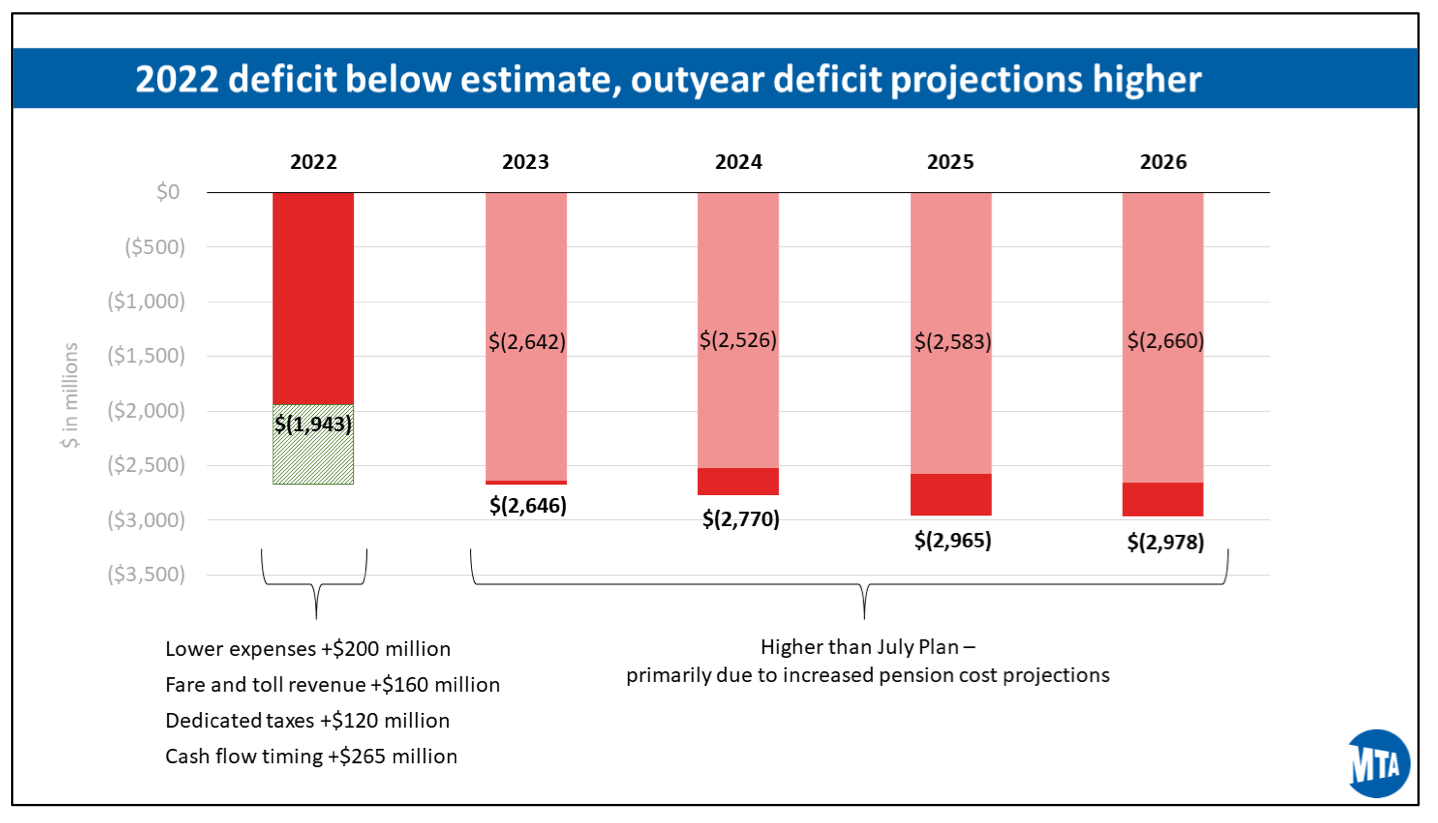

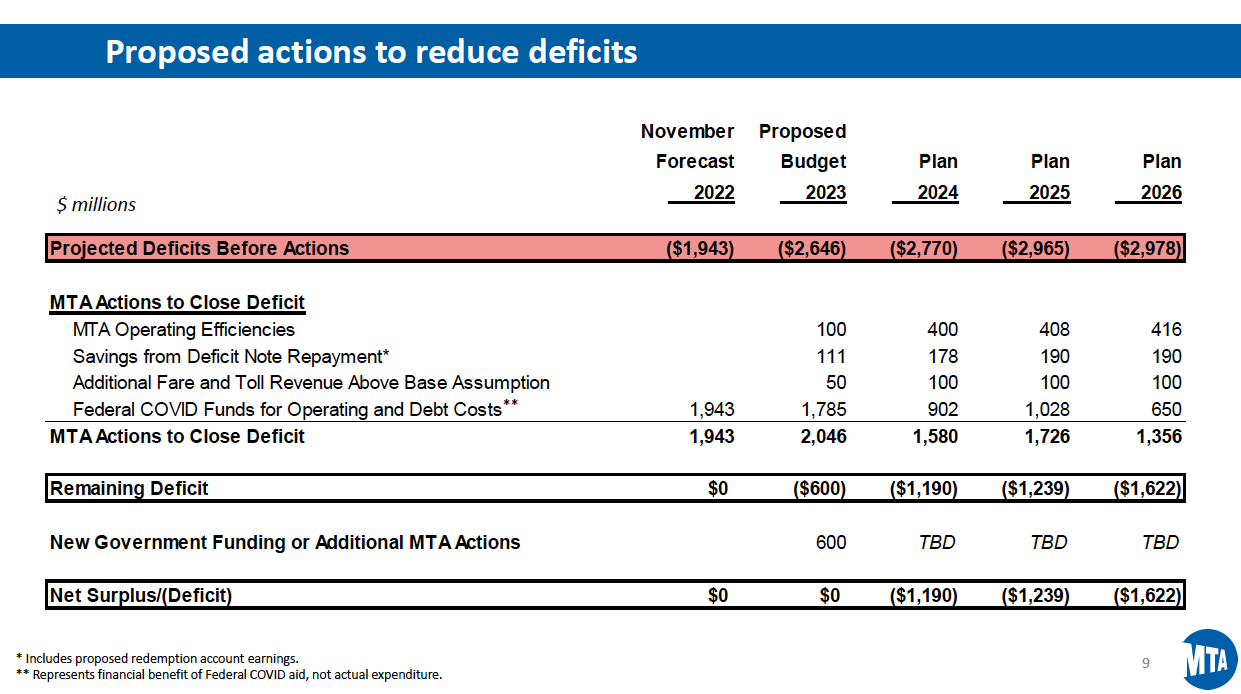

Pulling $2+ billion in fare and toll revenues out of the system each year wreaks havoc in an operating budget that approaches $20 billion per year once debt service is included – an operating budget that, by law, has to be balanced each year. This is where the federal COVID aid provided in 2020 and 2021 comes into play. The new financial plan estimates that, when the books close at the end of this month, the 2022 deficit will have been $1.94 billion, which will be paid for by federal COVID aid (see italicized paragraph below). (This deficit is less than had been predicted earlier this year, but about one-third of the savings are just a timing shift that increase deficits after 2022.)

But after 2022, the remainder of the new five-year financial plan projects annual deficits averaging $2.8 billion per year over the next four years.

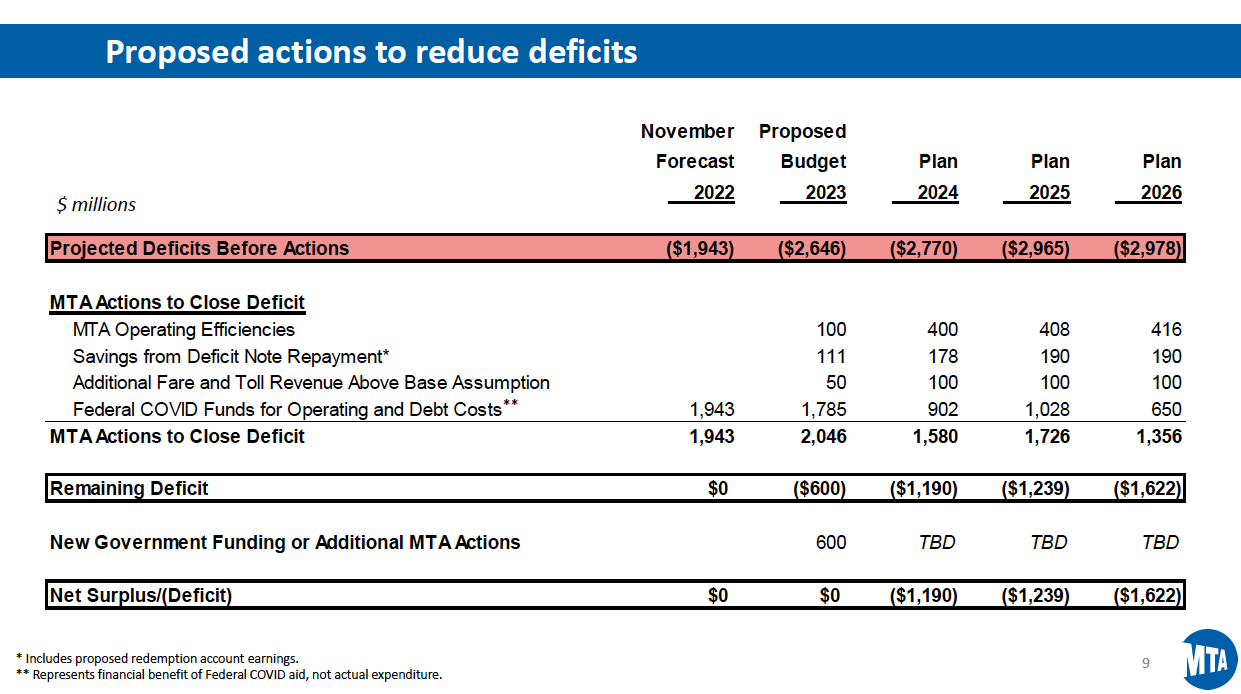

And that’s more than they can stretch the remaining COVID aid. The financial plan says that once the federal COVID dollars pay for the $1.94 billion 2022 deficit, “…approximately $5.6 billion of COVID funds will remain (see below). This funding will cover only a portion of the deficits projected for 2023 through 2026, which total $11.4 billion. The November Plan proposes to lower these deficits through a series of MTA actions, including applying COVID funds to offset MTA liabilities and cover a portion of the deficits in each year of the Plan.”

(Addition: The MTA reached out 12/9/22 to clarify something – for purposes of public presentations, when they say “Federal COVID aid,” they don’t mean the actual federal appropriations from CARES, CRRS, and ARP – that money has already been spent, because they were reimbursable grants. The MTA is referring to their own money that was displaced by the federal COVID aid, which they instead rolled over. They estimate that $5.6 billion of their own money, displaced and freed up by the federal COVID aid, will be remaining in January 2023. As the slide below shows, the new financial plan pencils in $4.4 billion of that $5.6 billion (1,785 + 902 + 1,028 + 650) over 2023-2026 to smoothe deficits, and the other $1.2 billion is not shown but is held in reserve to smoothe the 2027 and 2028 deficits.)

For 2023, the financial plan starts with that $2.65 billion operating deficit projection, then proposes to close about ten percent of that gap ($261 million) with cost savings, debt service changes, and more fare/toll money. The plan also proposes using about one-third of the remaining federal COVID money ($1.785 billion) to lower the projected deficit to $600 million.

But that reduced operating deficit would still be $600 million more than the MTA is allowed to run. So the new financial plan contains this plug:

“The 2023 budget assumes $600 million in additional government funding and/or additional MTA actions, both of which have not yet been specified. If no additional government funding is made available, MTA actions could include further expense reduction, additional revenues, or acceleration of federal COVID aid to achieve balance for 2023 that would have otherwise been used to reduce deficits in the years after 2023.”

MTA CFO Kevin Willens told the MTA Board that if the $600 million is not forthcoming, they would present cost-cutting and/or fare-raising alternatives at the February meeting. They were not specific as to which level of government the $600 million should come from, but the timing suggests that for 2023, they are primarily looking at state and local. (The next Congress doesn’t look like one to pass much of anything during January and February.)

Looking beyond 2023, the new financial plan proposes operating efficiencies, savings, and the use of federal COVID funds to get the $2.8-$2.9 billion per year projected deficits in 2024, 2025 and 2026 down to the $1.2 to $1.8 billion per year ballpark.

Revised slide with 2nd footnote added 12/9/22.

Willens said “But we need more than just a one-shot 2023 solution. The remaining $1.2+ billion deficits after 2023 need recurring funding solutions. Without new, recurring revenues, the Board will have to look to larger fare hikes, service cuts, and head count reduction to close the remaining gaps.”

What next?

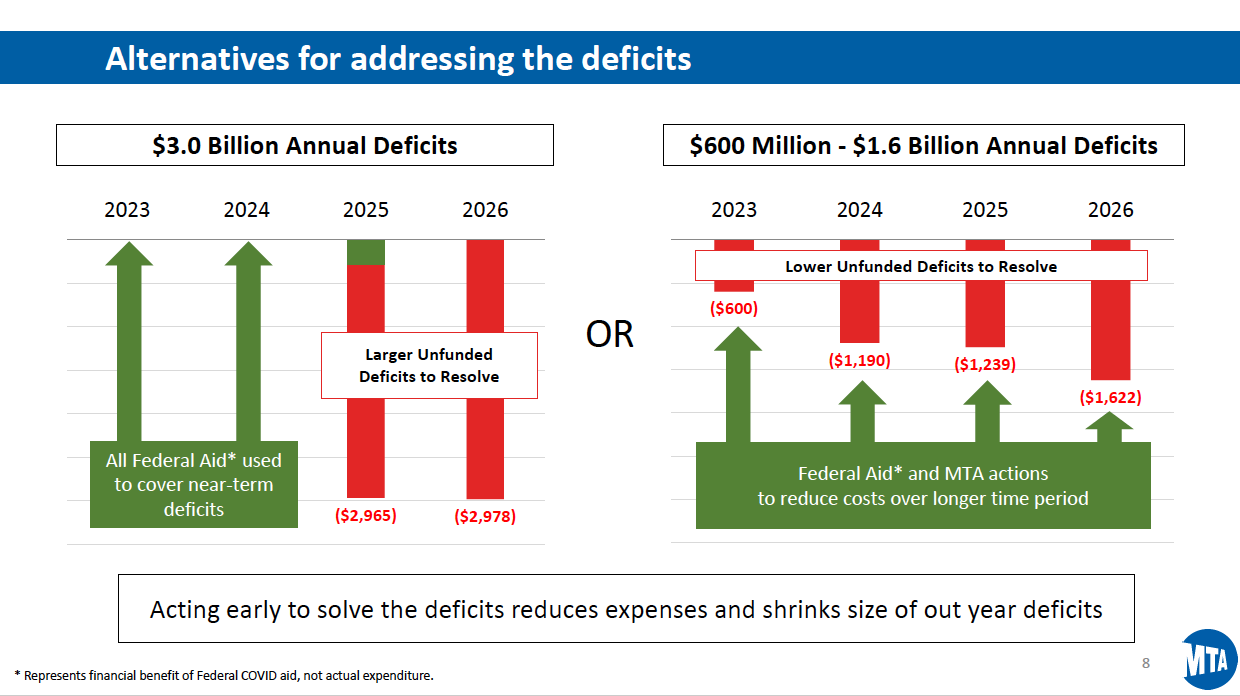

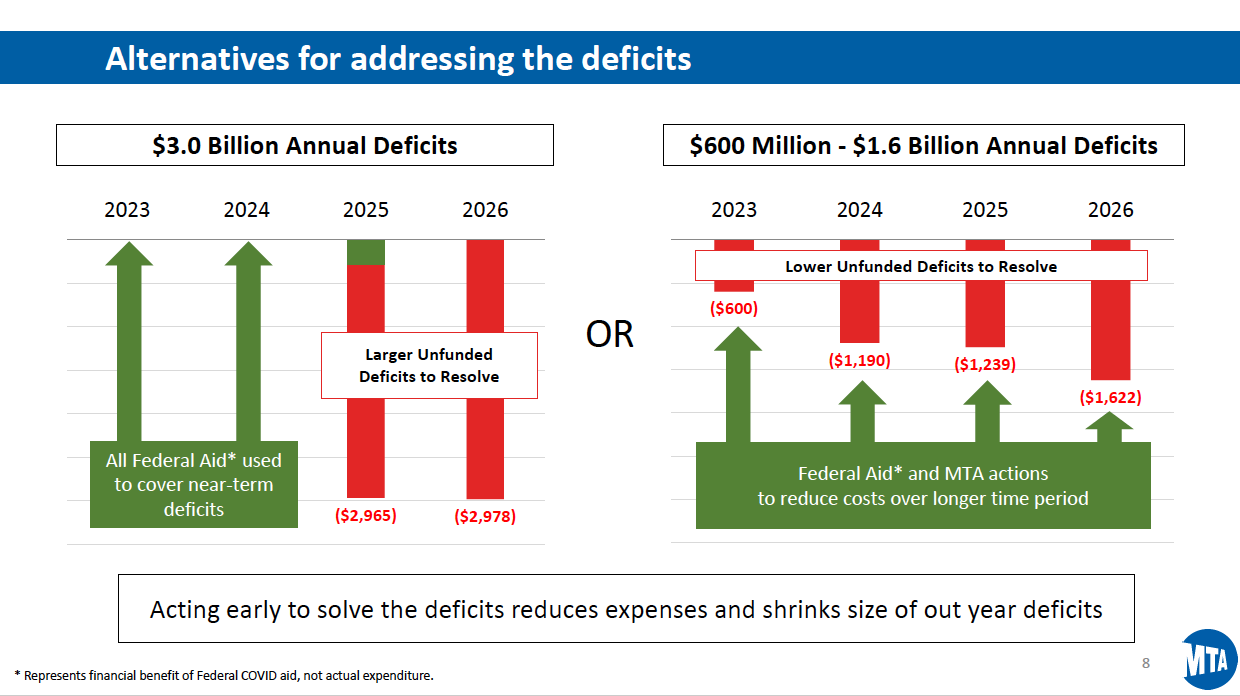

Assuming that the MTA can, through some combination of cost-cutting, financial rearrangement, and the good graces of Albany and Gracie Mansion, find $600 million in the next 12 months, their deficit problem still doubles in 2024, even after their projected $902 million spend-down of COVID aid. This is why the MTA leadership is presenting the Board with a decision on the COVID money – follow their current plan, to spread the COVID money out over the next four years, or spend it all now, in 2023 and 2024, making the problems much worse in 2025 and 2026?

Revised slide with footnote added 12/9/22.

The MTA Board could act on this choice as soon as its December 21 meeting, or could wait until next spring. But the choice is about when they hit the “fiscal cliff” and the relative size and slope of the cliff, not whether or not they are going to hit one. Stretching out the COVID aid through 2026 (the right-hand choice in the above slide) would require hard decisions in 2023 and very, very hard decisions in 2024. Applying all the remaining COVID aid to the 2023 and 2024 (the left-hand choice above) would avert the need for hard decisions in 2023 and 2024 budgets but would force the Doomsday Scenario in late 2024, where the MTA abruptly (seemingly) has to say it will impose massive service cuts unless some combination of Congress, the state, and the city give them several billion dollars per year in additional operating subsidies, in perpetuity, with no end in sight.