July 7, 2017

Last week the Trump Administration, through the U.S. Department of Transportation (U.S. DOT) released a new notice of funding opportunity (NOFO) for $1.5 billion in federal infrastructure grants. The INFRA grant program replaces the Obama-era FASTLANE program and makes some key revisions to how the federal government evaluates and selects projects. The Administration is right to update the program. Eno provided a set of comprehensive revisions earlier this year (See: Life in the FASTLANE).

Some reforms are in the right direction, but unfortunately the revised program falls short of the reforms needed to ensure the program truly works for freight and gets the most out of limited federal dollars. After an in-depth review, there are seven main takeaways:

- It does not (and cannot) do much about emphasizing freight projects.

The first Eno recommendation in the 2017 FASTLANE report was for Congress increase the amount of funding and target it to freight projects with national significance. The new INFRA program does not increase the amount of money available nor does it change eligibility. Increased funding is a legislative action, and therefore the Administration had little flexibility to address this directly. However, in the selection criteria (see below), freight is not emphasized any more than it was in the 2016 round of funding.

- The NOFO improves the evaluation criteria but does not demonstrate how U.S. DOT will use them to select projects.

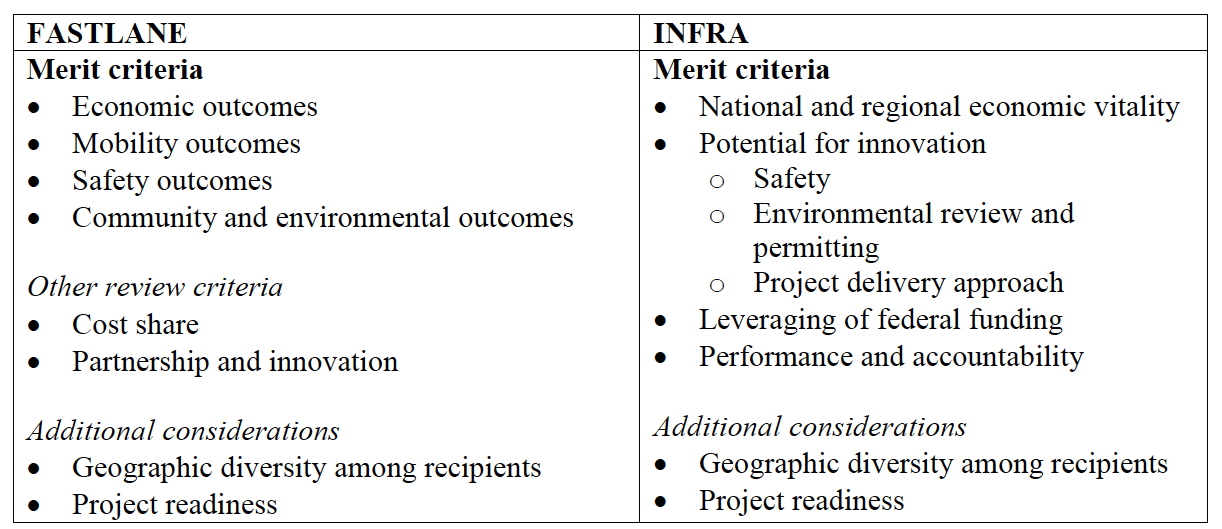

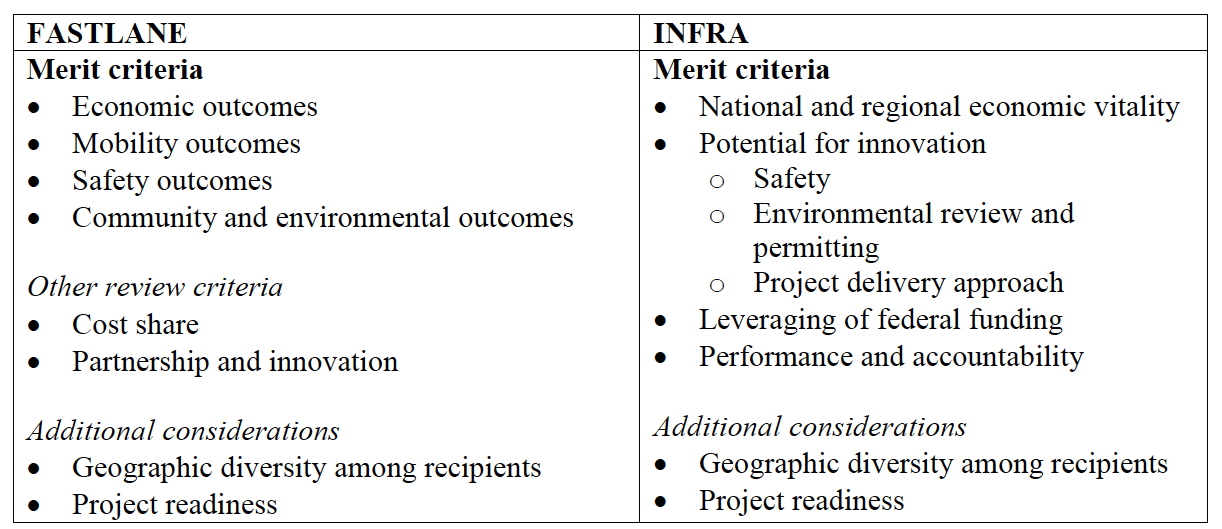

Eno’s second recommendation was to create greater transparency, assign and weight criteria, and publish the results of the evaluation in project selection. Unlike funding and eligibility criteria, this is an area where U.S. DOT has a tremendous amount of flexibility. The INFRA program did update the selection criteria, and the merit criteria for project selection hinges around four “key performance objectives” (KPOs) (see these compared to the old FASTLANE criteria in the table from a DOT fact sheet). But instead of defining how U.S. DOT will use the criteria, the NOFO explicitly states, “the Department is neither weighting these criteria nor requiring that each application address every criterion.” Unless something changes during the evaluation process, U.S. DOT will select projects in the same opaque manner that it did with TIGER and FASTLANE.

- It goes beyond traditional infrastructure projects and encourages operational improvements to address congestion and safety

The first KPO the NOFO lists is national and regional economic vitality. The NOFO requests that each applicant perform a benefit-cost analysis and other data-driven evaluations that demonstrate how the applicant’s project will address the national and regional economy. It specifically calls out examples of projects that can do this: addressing congestion in urban areas, using variable road pricing, filling service gaps in rural areas, and encouraging private economic development. In an improvement over FASTLANE, U.S DOT includes projects that address economic vitality through better roadway operations, instead of just more concrete and asphalt.

- It encourages innovation but in a confusing and unaccountable way

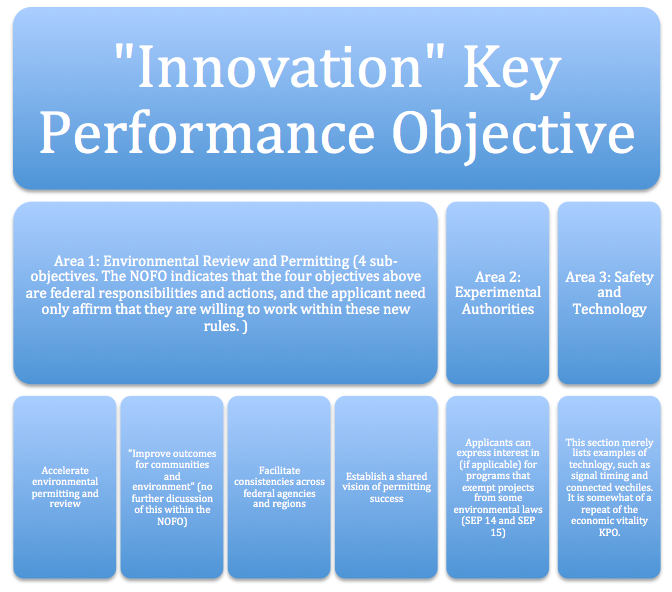

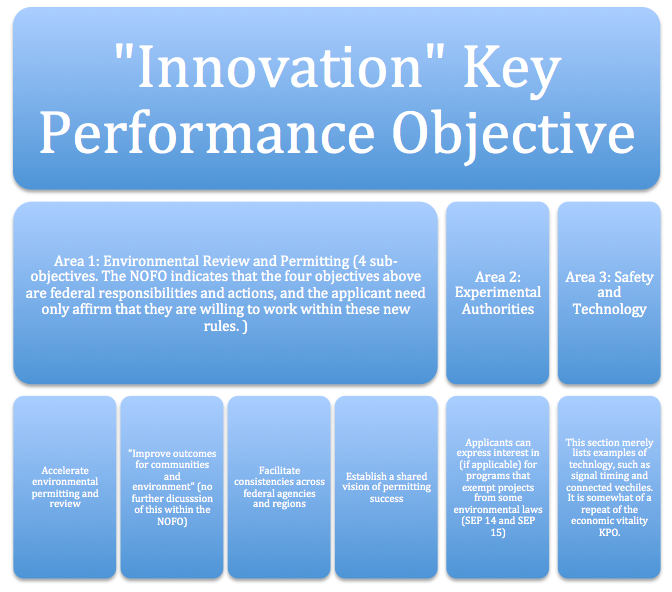

The KPO for innovation is unclear. The NOFO indicates that U.S. DOT wants to see more innovation, particularly in new approaches to streamline the permitting process, as a goal of the project. However, the NOFO lists several ways in which the broader Administration aims to streamline the permitting process across departments and allow for experimental project delivery. All applicants need to do is indicate whether they are interested in testing out the Administration’s streamlining efforts. The table below summarizes it, showing all of the sub-objectives that summarize DOT initiatives rather than specific action items for applicants. Some of this section includes objectives such as “improve outcomes for communities and environment” without any further explanation as to what that means or what DOT is looking to achieve. Not only is “innovation” not an objective (it’s a means to an end), applicants have little power to actually streamline the federal process themselves, so the “innovation” objective is merely checking a box.

- It encourages project accountability but doesn’t specify federal measures for federal dollars

The Eno recommendations call for more performance metrics and accountability in the process and the NOFO creates a method for devolved performance measurement. Instead of setting consistent metrics tied to federal goals, the Administration leaves it to applicants to create their own metrics for each project. Based on these locally-developed metrics, the Administration could potentially withhold INFRA funding if the agency does not meet them. It is hard to imagine local project sponsors setting targets that they are unsure they are able to reach, particularly if millions of federal dollars at stake. This appears to incentivize project applicants to create soft or easy performance targets that might not actually achieve much accountability. It is an odd approach for devolved accountability.

- It places more emphasis on the project’s non-federal share

Eno recommended placing greater emphasis on leveraging non-federal dollars, and the NOFO elevates this criterion to one of the four KPOs. Using the INFRA program to encourage greater state, local, and private investment in infrastructure is an important objective. Under Obama’s FASTLANE, the average federal share was 21 percent, well below the 60 percent maximum. We will have to wait until DOT announces the winning projects to see if a greater emphasis on leveraging actually results in a reduced federal share.

- It is explicit about the need for geographic diversity but it is not transparent about it.

Eno recommended that U.S. DOT be transparent and explicit in how it awards projects to achieve some form of geographic diversity, and should keep the equity aspect of the selection process to a minimum. The INFRA NOFO is explicit in the need to geographically distribute the funds, but it does not say how it intends on achieving this. When DOT announces the final awards, it will be helpful for the transportation stakeholders to understand how the Administration considered geographic diversity, and how future applicants can compete to meet federal goals.

No federal grant program is a stagnant process. Each year DOT improves upon the goals, objectives, and methods for selecting projects in the aim of better targeting limited federal dollars. A federal grant program, particularly one with a freight component, is too important of an opportunity to neglect. DOT should retain an open process and assess feedback from stakeholders on how to make this round and future rounds shape INFRA into a better program.