(Editorial Note: This is an extract of the presentation made to the Eno Transit Executive Program, which took place between April 17-23 in Washington.)

The development of the London Overground, Crossrail and light rail projects

Background

London (population 8.6m), like many cities worldwide has been stable in terms of the provision of transportation for many years. Only two Underground lines were added over the last 50 years, in 1972 and 2000, both to ease congestion in the city center.

London is dependent on rail supporting 4 million jobs, with a high concentration of employment in the City (130,000 jobs per square Km). 50% of all UK rail journeys involve London and the modal share of rail for all modes on journeys is 60%.

London’s continued economic and population growth therefore relies on effective and efficient National Rail services linking into the Underground routes, and the bus network, which until recently were run as franchises from National Government. The government franchise system, whilst providing for cost effective service, did not meet the needs of investment in capacity in the form of major rail projects and levels of overcrowding, already at high levels, were projected to become unsustainable.

A compelling case for change

The breakthrough came in 1999 with the enactment of greater self-government for Greater London, followed by the election of a Mayor of London (initially Ken Livingstone, later Boris Johnson) in 2000. The legislation implementing this change required the Mayor to implement strategic planning for London, particularly in the areas of economic development, housing, social inclusion and growth.

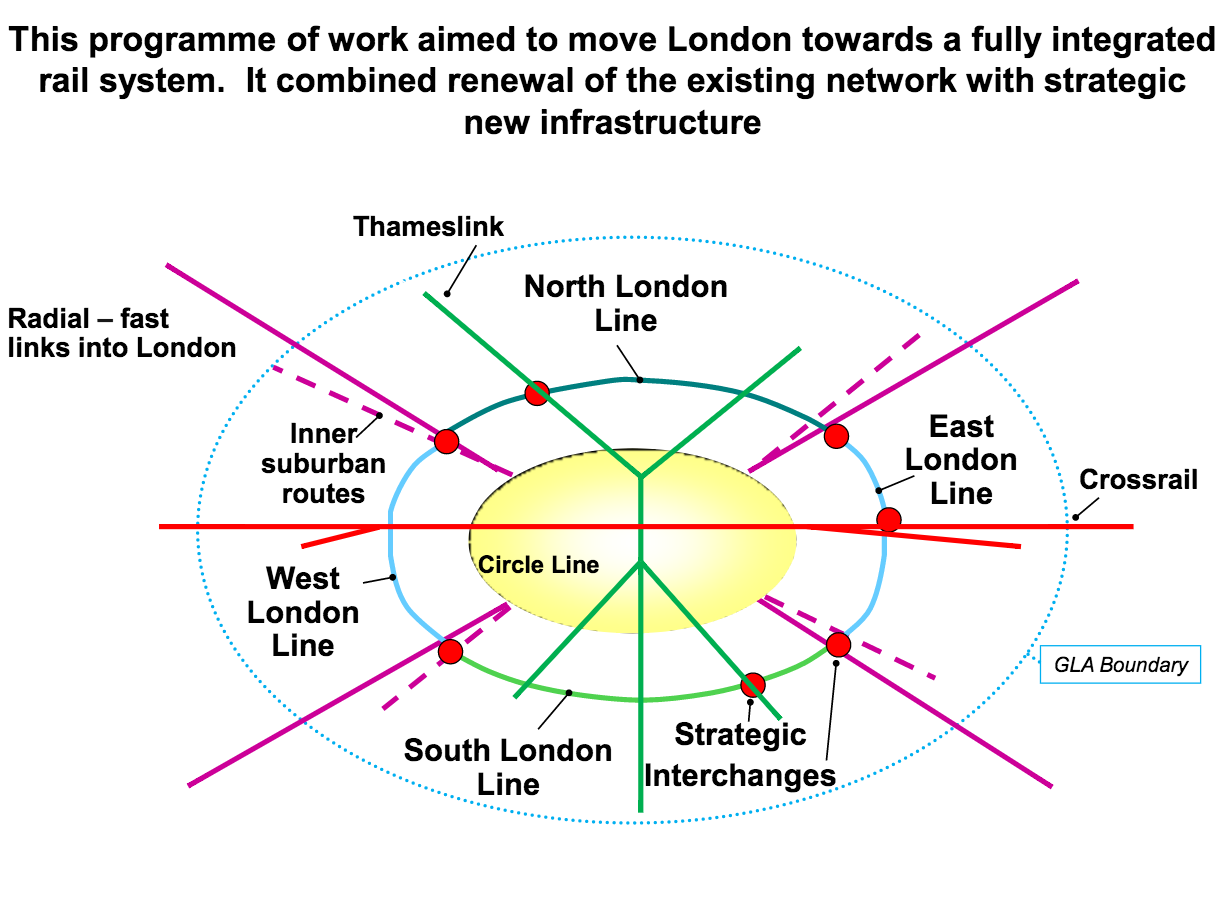

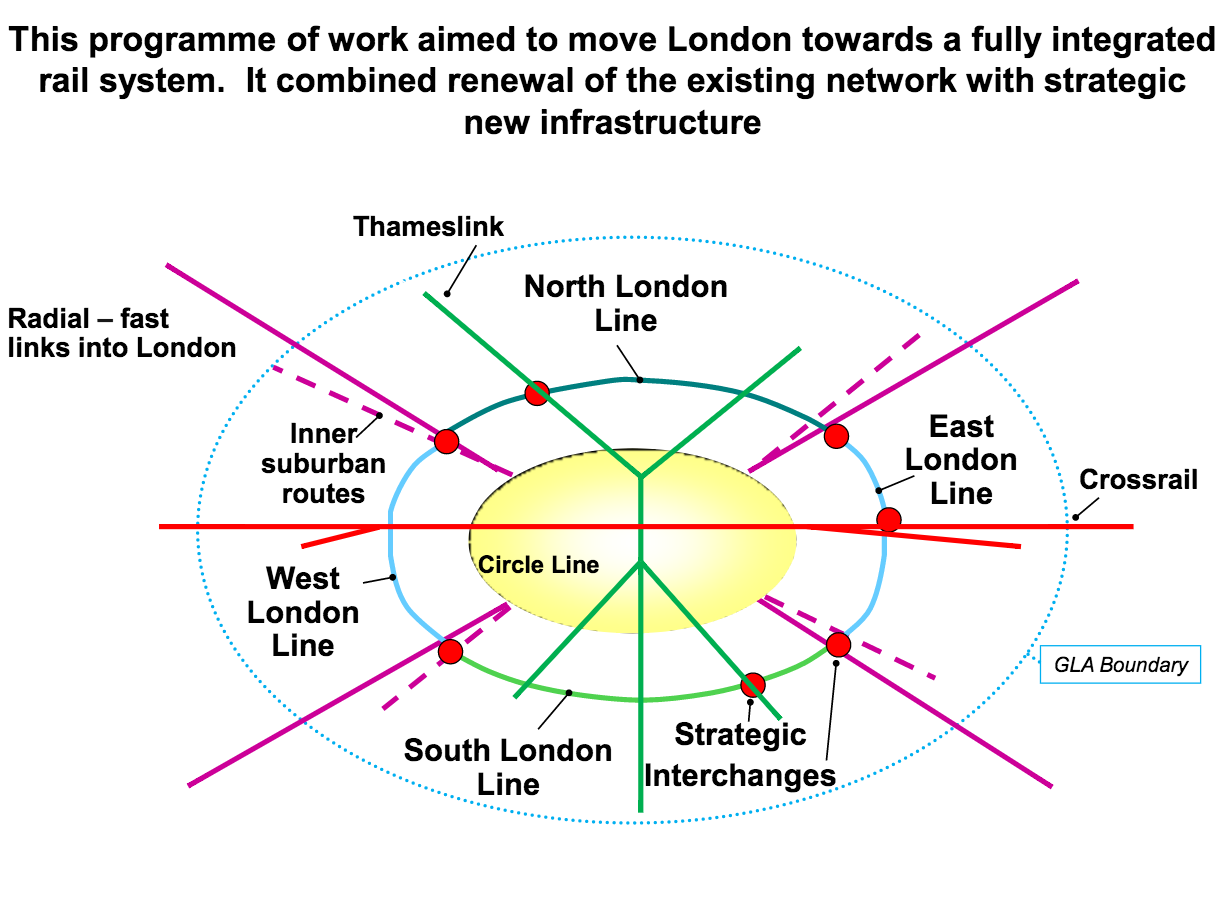

Integrated planning and control of rail and other transport modes was seen as essential if the city was to grow sustainably. This had to include National Rail as more and more people were accommodated in the outer areas away from the Underground network. The solution also had to include major projects to address the need for increased capacity but also provided for cross London and orbital journeys, so far the preserve of the road network.

The Congestion Charge first levied in 2003 for road vehicles entering London was successful in raising money and initially deterred some non essential road journeys, although as the city has continued to grow traffic levels entering Central London are now back to pre congestion charge levels.

These issues led to an increase in the powers of Transport for London to run rail franchises and undertake major projects.

There were stark choices at the time between continuing the development as a world-class city or attempting to stabilize population and economic growth. In choosing the former it became apparent that this would not happen with major developments in all rail services serving the city.

Business cases

The traditional business case methodology as prescribed by government was essentially about transport, more passengers, faster journeys (journey time benefits), costs (moderated for optimism bias) and projected income. It soon became clear that using this transport-focused methodology, the case for the massive investment needed could not be made.

The real case was all about sustaining the growing economy of London and fostering social inclusion. There were many suggestions around the area of creating jobs more spread across the city but economists made a strong case based on London’s key export – finance and business services. This led to an important city concept where the most efficient way of conducting such business is in one concentrated location. This is now referred to as “the agglomeration effect”.

The other key component not reflected in traditional transport business cases is social inclusion. It was important to find a way of expressing this in a simple way rather than just saying that it is an important policy issue. This was expressed in economic terms by looking at the economic case. The agglomeration effect can only work with sustainable high volume transport (Hong Kong style), requiring a massive increase in capacity over the legacy system. However, for example, for every job in the financial and business services sector there are 4 support jobs (IT, maintenance, cleaning etc). These jobs do not pay as well, but the city cannot function without them.

The agglomeration effect formed the business case for the massive Crossrail project, but social inclusion was also a major factor, particularly in justifying upgrades of radial main line railway routes and the completely new Overground network with its orbital line now completed right round London. This addressed the need to provide a viable alternative to the car and importantly provided alternative non-city-center routings for many cross-city journeys. Both Moscow and Paris have adopted a similar approach.

This led to a vision for a new integrated transport system for London.

Convincing government

Repositioning transport investment as a solution to economic and social needs and opportunities was a game changer in terms of acceptance of the need to invest in transportation. It is now a centrepiece of national UK government policy.

It was necessary, but not sufficient, to undertake a transport revolution of this scale.

The key government concerns were how these developments would be funded and was there confidence that the team could deliver within the timeline and costs projected.

Funding of Transport for London (TfL) comes from the fare box and from the national government. TfL’s London fares are relatively high so the fare box is important to overall funding. The large increases in passengers (up to 400%) meant that provided capital funding was available, and smaller projects (Docklands Light Railway and initial phases of the London Overground) were seen as sustainable.

The massive Crossrail project, the final and largest piece of the jigsaw at £16.7bn, needed a more fundamental approach. This eventually took the form of a roughly equal three-way split:

- Securitized projected income from fares;

- A London business tax (in three bands depending on how far an individual business from a Crossrail station; and

- And national government funding (reflecting the value of the project to the whole of the UK).

Project delivery

Delivery of all these projects depended on a strong client team. A specific dedicated client team was set up for Crossrail (Crossrail Ltd) to ensure that cost overruns did not undermine normal transport provision. Many of the contracts were designed and built with particular emphasis on ensuring that the size of contracts was proportionate to the capability of UK suppliers to deliver. Minimizing risk was the other objective. For example, Crossrail needed 65 new 9-car trains, so the procurement contract included depots and maintenance of the trains.

Train service delivery

For London Overground and also Crossrail, there was much pressure from within to implement an in-house operation. However, benchmarking national rail franchises against the in-house London Underground operation suggested that this was not cost efficient. The franchises were not delivering in terms of quality, nor investment in growth. Additionally, the previously fragmented fare system in London with 19 rail operators all working to maximize revenue (as they took revenue risk) was fine for long distance rail, but not effective in providing an integrated fare and transport solution against London’s objectives.

The method selected for service provision was based upon what was termed a concession, not a revenue risk franchise. TfL funded and procured the investment in new infrastructure, stations, and trains. TfL came up with an integrated fare system and introduced the popular Oyster smart ticketing. The concession was a competitive procurement competition for the provision of a defined service without revenue risk but with incentives for performance including revenue collection. Service levels were tightly specified as was service quality, and was independently monitored.

The results

The result of investment in high frequency, high quality Overground services has resulted in spectacular traffic growth in what were in some cases seen as unpromising. And there is clear evidence of regeneration in inner city areas. Importantly the passengers love it and so do the politicians. The May 2016 Mayoral election in London focuses on how the Overground can reach out further.

Crossrail is complete in terms of the 44km of tunnel running across London and remains on target for opening in 2018. The new railway will run from Reading and Heathrow in the West across Central London, the West End, the City (financial quarter) and Canary Wharf to the East out to Shenfield and Abbey Wood.

What next?

Interestingly, there are efforts to try and replicate this in the north of England by creation of an “agglomeration effect” there by grouping the economies of northern UK cities – Liverpool, Manchester, Leeds and Sheffield into one economic region linked by rail (HS3). This is also being replicated in Scotland by a similar rail project to amalgamate the commercial centre of Glasgow, through the Central belt of Scotland with Edinburgh the center of Scottish government.