As part of the Eno Center’s release of its new paper, Refreshing the Status Quo: Federal Highway Programs and Funding Distribution, this article explains precisely how the FAST Act of 2015 ties each state’s annual federal-aid highway funding total to the last year of the SAFETEA-LU Act (fiscal 2009), which in turn relied on real-world apportionment factors as of the year 2007, and the distribution of earmarked projects by well-placed members of Congress in the summer of 2005.

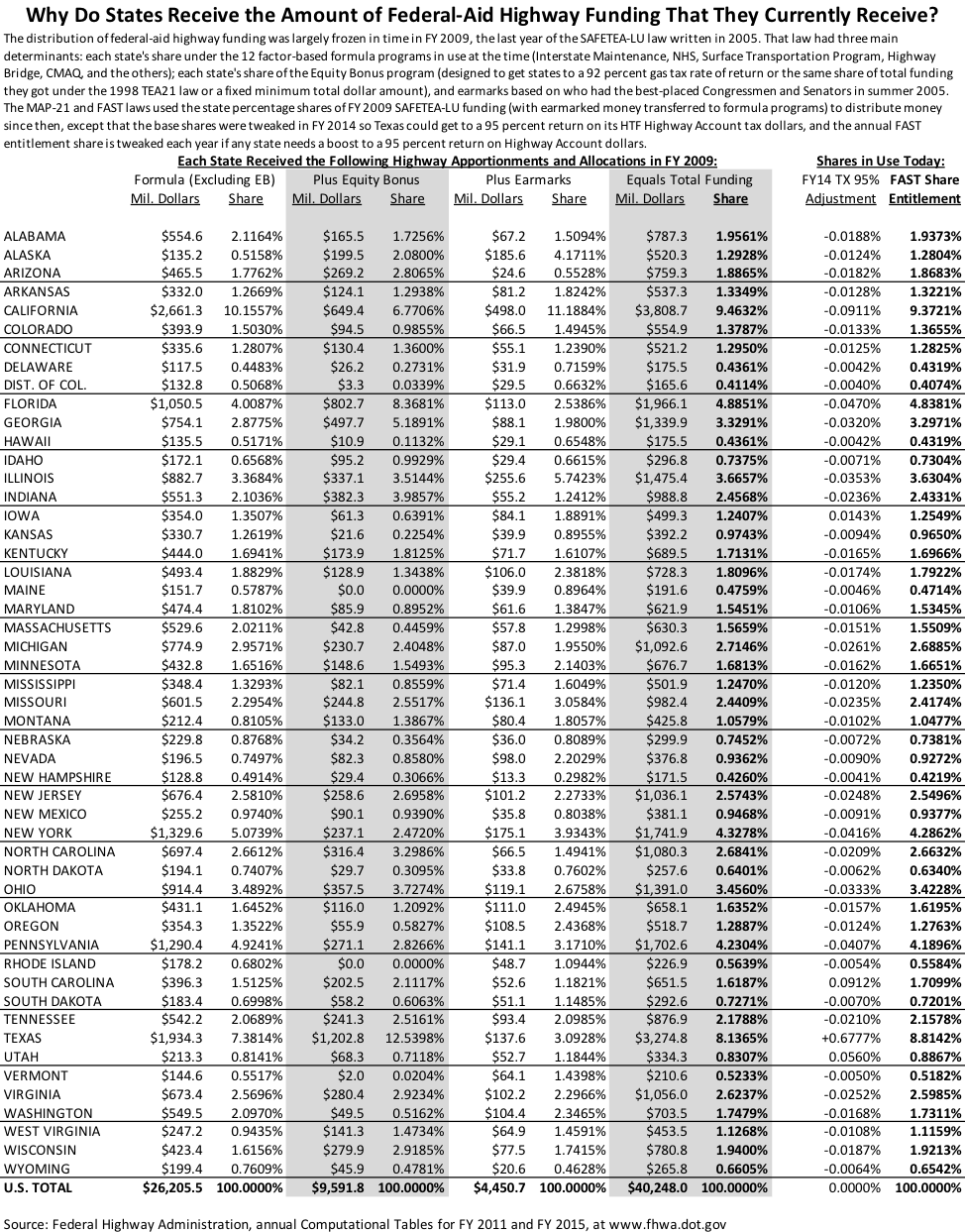

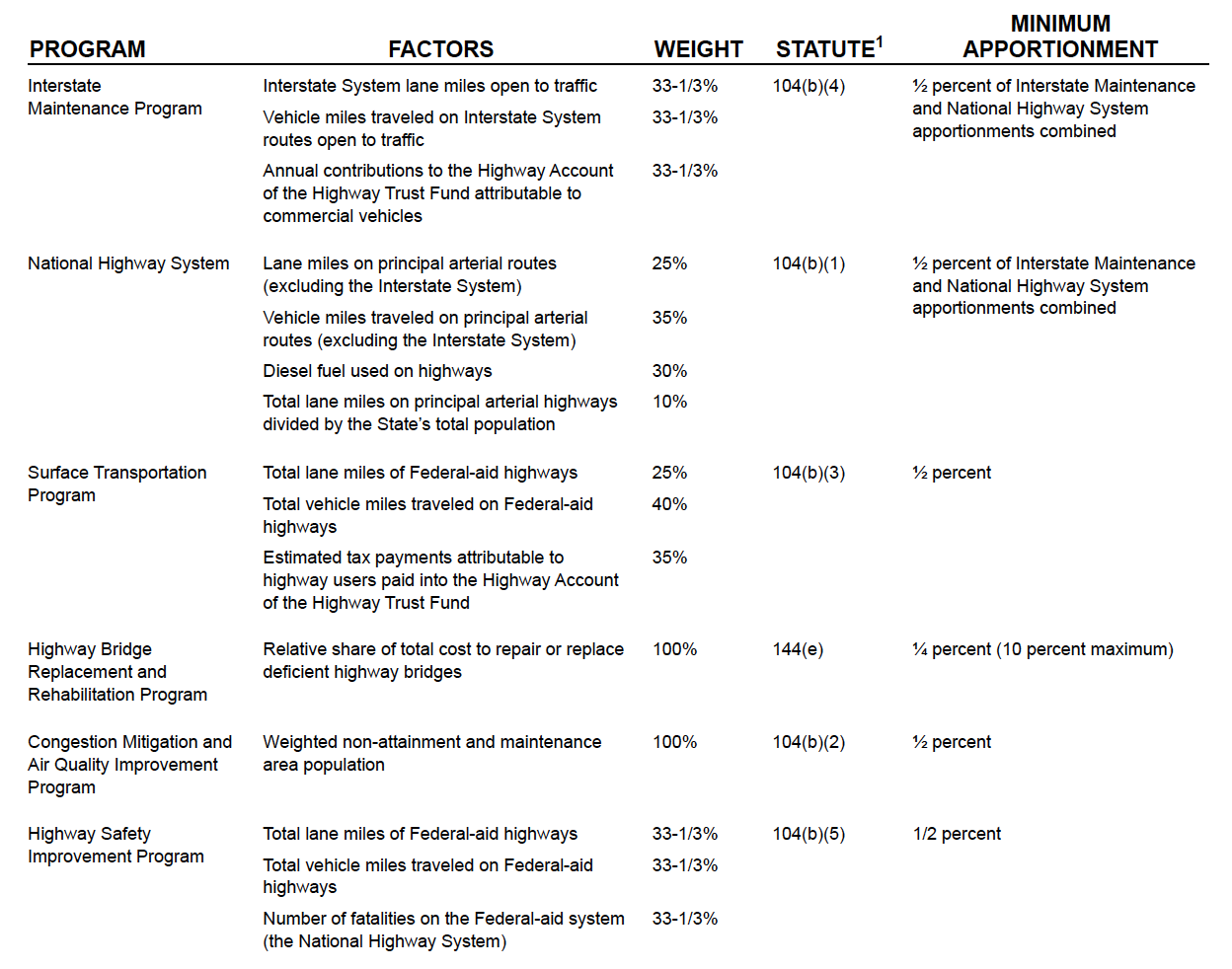

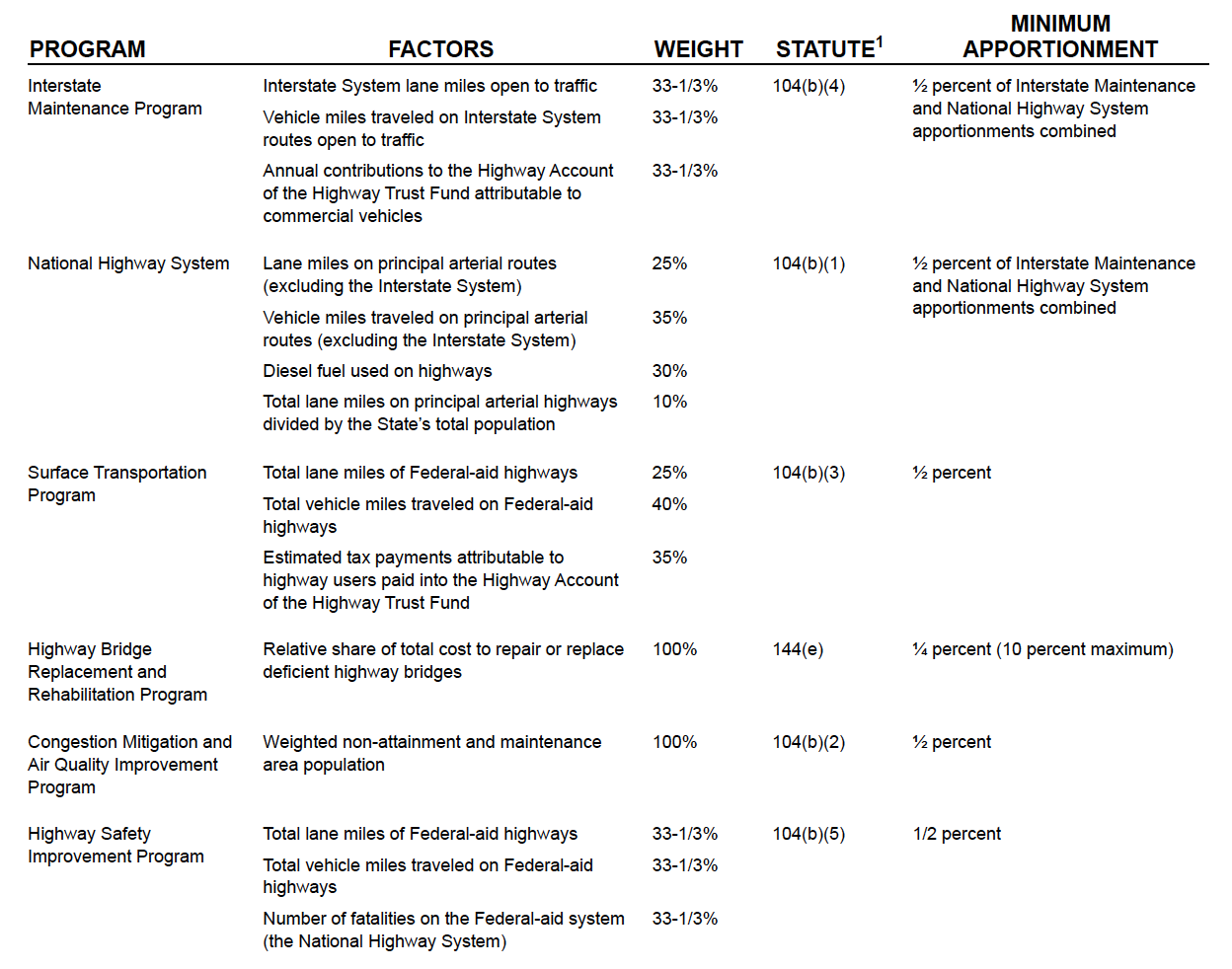

SAFETEA-LU. Under the 2005 SAFETEA-LU law, each year for fiscal years 2005-2009, the Federal Highway Administration had to update their real-world data on a variety of formula apportionment “factors” for the 12 factor-based formula programs. Six of those 12 programs took up about 95 percent of the total factor-based formula funding – these “core programs” from the SAFETEA-LU era, and their apportionment formulas, are shown below.

Since apportionments must be made on the first day of the fiscal year (October 1), this means that the FY 2009 calculations were made by FHWA in the summer of 2008, and that in turn means that they were based on data collected in 2007 (at the latest).

Then, under SAFETEA-LU, a fearsomely complicated program called “Equity Bonus” added as much contract authority to the program as necessary to make sure that each state’s funding total met at least one of the following three criteria:

- A “rate of return” on Highway Trust Fund – Highway Account tax payments of at least 92 percent (a state’s share of total apportionments and high priority project earmarks had to be at least 92 percent of the state’s share of HTF-HA tax payments); or

- A guaranteed minimum total apportionment (plus HPPs), in dollars, that was at least a fixed multiple of the average total apportionment (plus HPP) dollars under the FY 1998-2003 TEA21 law (the FY 2009 multiplier was 121 percent of the TEA21 average); or

- For 27 specified states, a guaranteed minimum share of total apportionments (plus HPPs) that was equal to the state’s average share of total apportionments (plus HPPs) under the FY 1998-2003 TEA21 law.

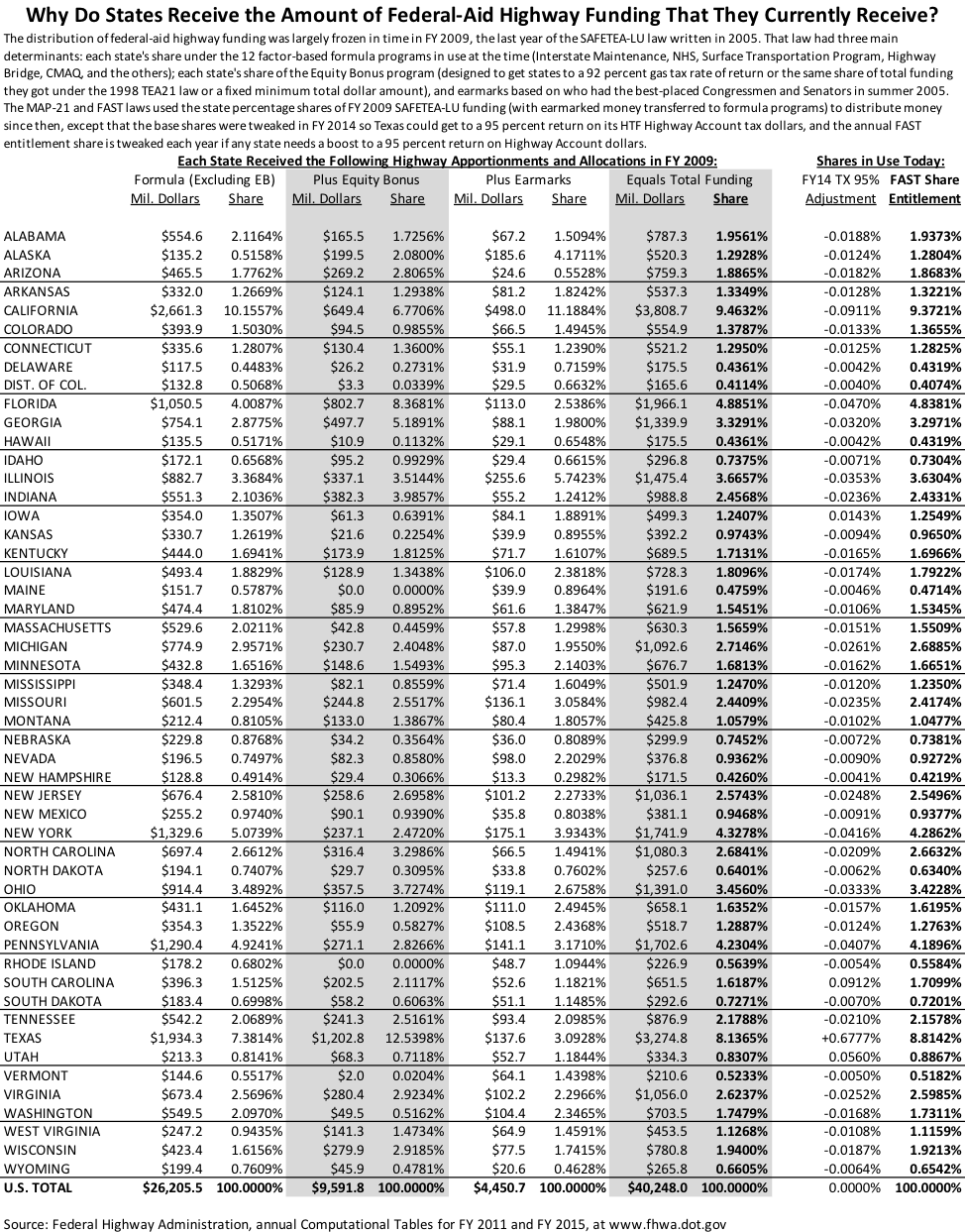

For FY 2009, 48 states and the District of Columbia received at least some Equity Bonus funding (the only two left out were Maine and Rhode Island). It took $1.2 billion in EB funding in 2009 to get Texas up to its guaranteed minimum 92 percent rate of return; it took $237 million to get New York up to its minimum 121 percent of the TEA21 dollar amount; it took $115 million to get Alaska up to its guaranteed minimum 1.1704 percent of total apportionments and HPPs. (For the full details, see Table 13 in the FY 2009 computational tables).

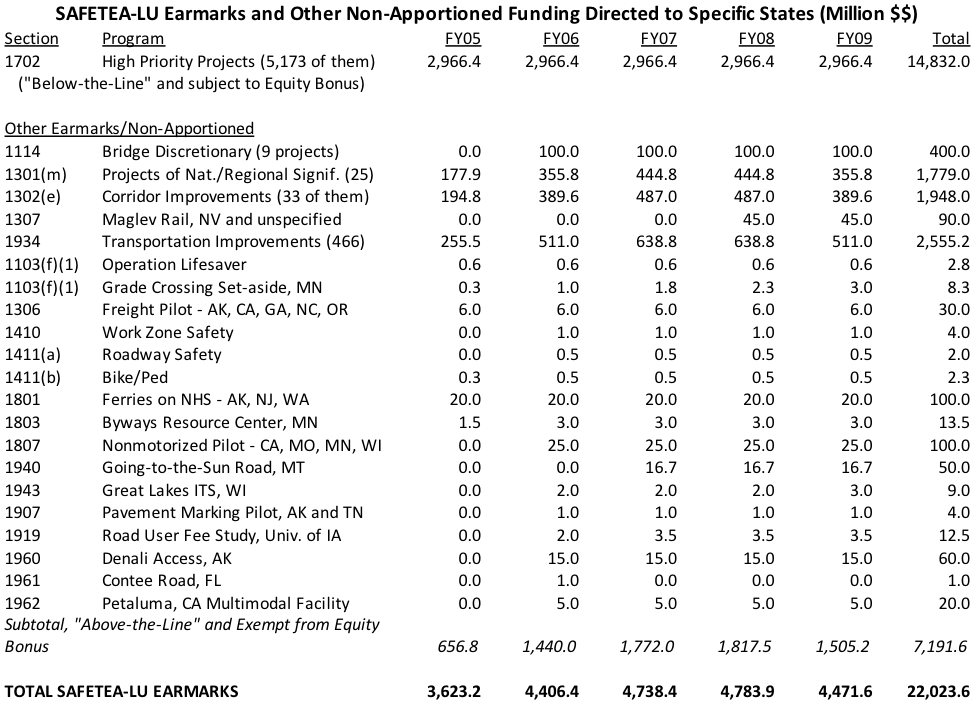

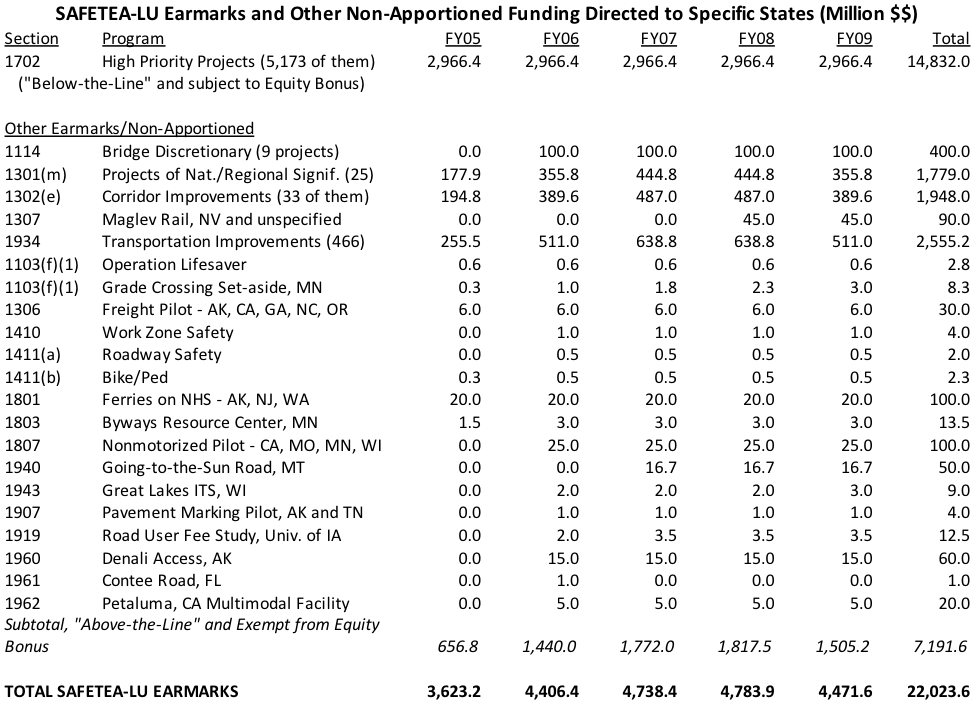

In total, for FY 2009, there was $26.2 billion in factor-based formula funding apportioned, plus an additional $9.6 billion in Equity Bonus funding (which was then spread around the six “core” formula programs), plus the $3.0 billion of high priority project earmark funding under section 1701 of SAFETEA-LU (5,173 designated projects given $14.8 billion in contract authority in five equal annual tranches of $2.966 billion).

Extensions and “above-the-line” earmarks. Once SAFETEA-LU expired at the end of 2009, the highway program functioned under a series of short-term extensions of SAFETEA-LU funding levels for fiscal years 2010, 2011 and part of 2012. During these extensions, an interesting problem arose. While it was easy to keep giving states more money in the amount of their expired SAFETEA-LU high priority projects under short-term extensions (since that money had already been accounted for in the Equity Bonus calculations, and the expiration of the earmarks simply meant that states got more Equity Bonus money to get them up to their guaranteed totals under one of the three types of EB guarantees), there was other SAFETEA-LU earmark money that was not as easy to account for.

Title I of SAFETEA-LU actually had $22 billion in earmarks. Two-thirds of that money was the high priority projects in section 1702 that were “below the line” and thus counted towards the overall Equity Bonus guarantees. But the other third of the earmark funding – $7.2 billion – came in the form of “above the line” earmarks that were in addition to a state’s other funding guarantees. Not surprisingly, powerful committee chairmen and ranking members, and House and Senate party leaders, preferred this kind of earmark. These were also bigger – the HPPs averaged only $2.9 million apiece, but the above-the-line section 1934 Transportation Improvements averaged $5.5 million each, and the sections 1114, 1301 and 1302 earmarks together averaged $61.6 million each.

The FY 2009 tranche of above-the-line earmark funding (shown below) was $1.5 billion, and since budget rules allowed extensions to carry the same overall amount of FHWA contract authority as had existed in 2009, they had to spend that money on something or else downsize the next bill by $1.5 billion per year. It was decided that, during the extensions, states would receive extra money towards their core formula programs in the amount they were getting in FY 2009 in above-the-line earmarks.

MAP-21. When Congress finally was able to enact another multi-year reauthorization law in July 2012 (MAP-21), Congress did not have the energy to fight over formulas. So section 1105 of MAP-21 simply said that the FY 2013 dollar amounts given to each state would be the same as the total dollar amounts under the final SAFETEA-LU extension for 2012 (formula totals plus below-the-line and above-the-line earmarks). Then, for FY 2014, the total funding would increase a bit, but each state would get the same share of total funding as they did in FY 2012 (which was the same as FY 2009), except that if any state’s total 2014 apportionment, in dollars, was projected to be less than 95 percent of the dollar amount of the state’s estimated FY 2012 HTF-HA tax payments, their dollars would be adjusted upwards to the 95 percent tax payment dollar amounts, and every other state’s percentage shares of the total program would be adjusted downwards accordingly.

(The fact that the Trust Fund had gone broke in 2008 and was still relying on general fund infusions to stay solvent had made a mockery of the old percentage share of tax payments versus percentage share of funding donor state calculation, so MAP-21 changed it to dollars-in versus dollars-out. The staff who wrote the bill did not think that any state would actually trigger a 95 percent dollars-in threshold.)

Wouldn’t you know it, Texas actually managed to trigger the 95 percent rule in FY 2014, so their apportionment was adjusted upwards by $431.5 million, increasing their share of the total from 8.1365 percent to 8.8142 percent, and all the other states and D.C. saw that $431.5 million pro-rated and deducted from their appointments (and thus from their shares).

Once MAP-21 ended, FY 2015 was conducted under a clean extension – each state got the same dollar amount of total funding that they did in 2014.

FAST. The FAST Act of 2015 didn’t adjust the formulas, either. Section 1104(c) of FAST simply said “For each of fiscal years 2016 through 2020, the amount for each State shall be determined by multiplying [the annual FAST total funding] by…the share for each State, which shall be equal to the proportion that–(I) the amount of apportionments that the State received for fiscal year 2015; bears to (II) the amount of those appointments received by all States for that fiscal year.” The only exception was the same 95 percent dollars-in, dollars-out donor state rule as under MAP-21, applied anew each year.

So, under FAST, each state is still guaranteed the same FY 2009 total share (factor-based formulas plus Equity Bonus plus earmarks) of the total program, as adjusted by the FY 2014 Texas 95 percent donor state adjustment (which became the base FY 2015 total under the extension), plus any subsequent 95 percent donor state adjustments (all of which have gone to Texas, including the one for FY 2020 yesterday).

Summary. Through FY 2020 (the contract authority for which was apportioned to states yesterday), state funding totals are still tied to the real-world apportionment factors such as lane-miles, population, VMT, clean air attainment, highway fatalities, etc. as they existed in 2007, and to the total amount of earmarks that the legislators of each state were able to get in the pork-barrel bonanza that took place in summer 2005.

The only real-world factor since 2007 that has made any difference in overall state funding totals in the amount of gasoline and diesel fuel purchased for highway use in the Lone Star State.

Looking towards the future, the America’s Transportation Infrastructure Act of 2019 (S. 2302) approved by the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee on July 30 does provide $9.4 billion over five years (FY 2021-2025) for new formula programs tied to updated, real-world factors and metrics. But it also provides $249.4 billion (an average of $49.9 billion per year through 2025) for the existing formula programs, to be distributed to states via – you guessed it – the same old FY 2009 formula shares with 95 percent tax payment adjustments.

The table below shows each state’s totals for FY 2009 factor-based formula, Equity Bonus, and earmarks, and also the decreases in everyone’s share except Texas for the FY 2014 donor state adjustment which is still, through 2020, the baseline share for future apportionments.