November 3, 2017

Yesterday, House Republican leaders stunned the infrastructure community yesterday when they released a mammoth tax reform bill (H.R. 1) which included elimination of private activity bonds (PABs), a popular financing tool for certain types of infrastructure.

The House Ways and Means Committee will start to mark up the bill at noon on Monday, November 6, and the markup will continue “throughout the week as necessary” according to the committee. The legislation is expected to be on the House floor for a vote the week before Thanksgiving.

PABs are a type of bond to fund private projects that have a public benefit, and the interest for the bonds is exempt from federal taxation (just like the interest for bonds issued directly by state and local governments). The bond market considers PABs to be a part of the municipal bond sector.

Section 3601 of H.R. 1 would eliminate private activity bonds moving forward after the end of calendar year 2017 (though the deductibility of the interest on previously issued PABs would remain in effect). The section-by-section summary of the bill released by Ways and Means Committee Republicans justifies the change by saying “The Federal government should not subsidize the borrowing costs of private businesses, allowing them to pay lower interest rates while competitors with similar creditworthiness but that are unable to avail themselves of PABs must pay a higher interest rate on the debt they issue.”

The Joint Committee on Taxation estimates that the change would increase federal tax revenues by nearly $39 billion over the next ten years.

The change came as a complete surprise to the infrastructure community – the White House has been discussing significant expansion of PABs in its forthcoming infrastructure proposal. It was also a surprise to states and cities – Emily Brock, director of the federal liaison center for the Government Finance Officers Association, told Bond Buyer magazine that “We’ve had over 90 Hill meetings and there was absolutely no talk of advance refundings, private activity bonds, or tax credit bonds…”

The way that PABs work is as follows: each year, the Treasury Department gives each state a population-based total dollar amount of permissible PAB issuance for that year (the state minimum was $305 million in FY 2017, and California’s cap was about $4 billion). Unused PAB cap can be rolled over for four years before it expired. In calendar year 2016, according to the Community Finance Development Association, states collectively had access to $63.9 billion in carryover prior-year volume cap and $35.1 billion in new volume cap.

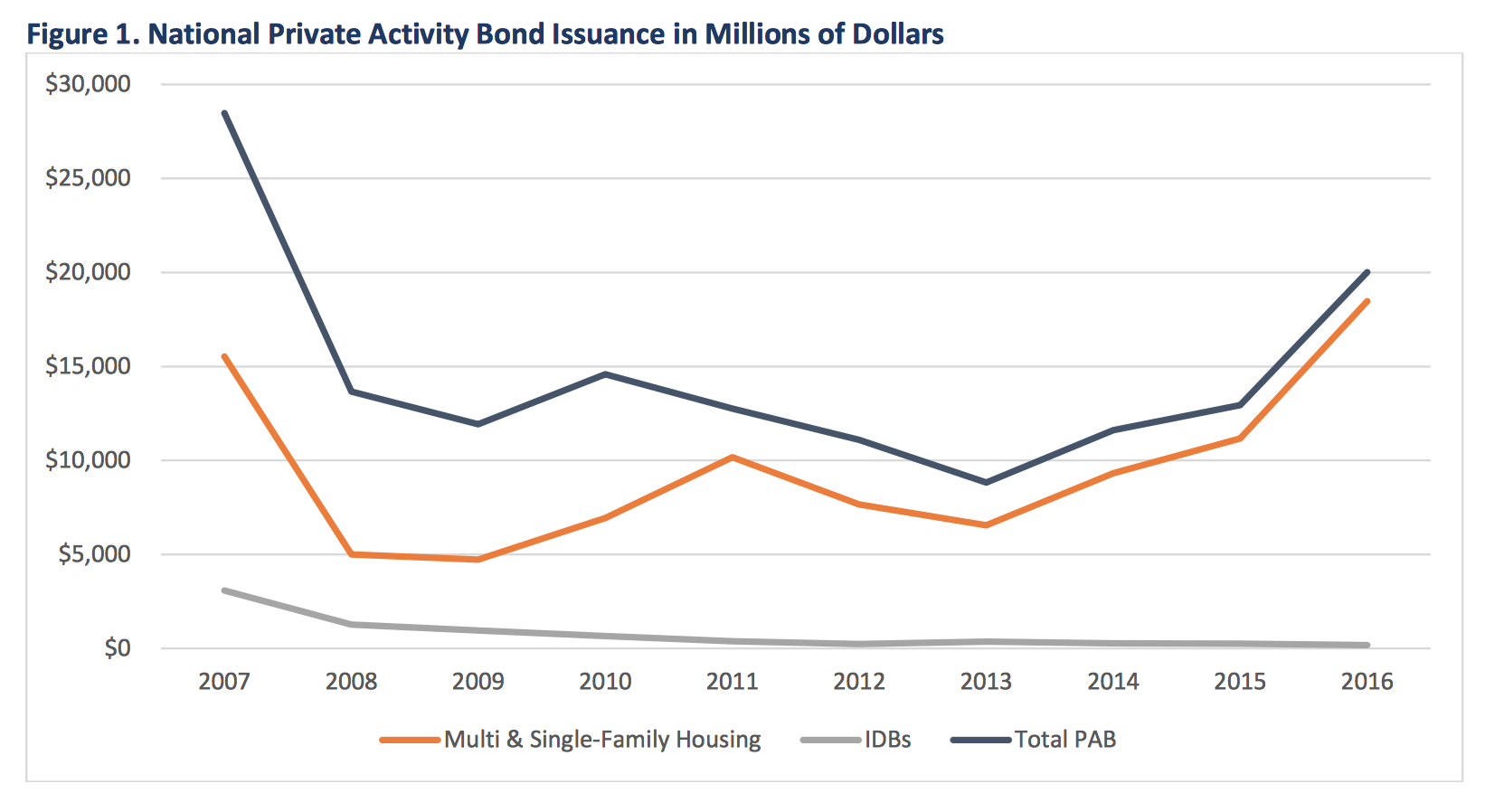

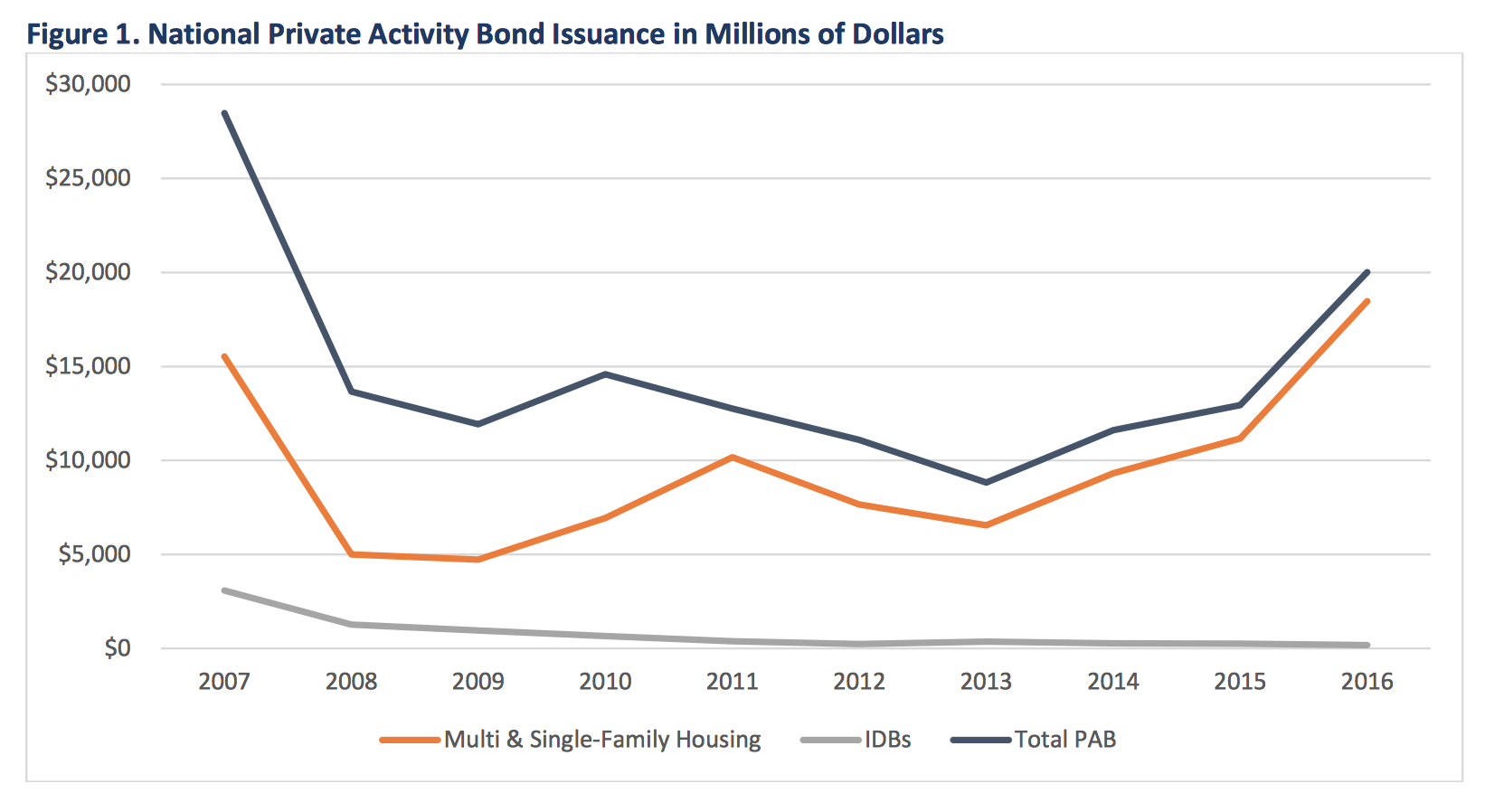

A total of $20.4 billion in PABs were issued in 2016, and $9.6 billion in carryover volume cap expired at the end of the year. This was a significant increase over the level of PAB issuance in recent years, as shown by the chart below (courtesy of a report by the Community Finance Development Association).

As the chart makes clear, about 80 percent of all PABs are for housing projects. (IDB = industrial development bonds.) But that 20 percent of the PAB market includes a lot of big-ticket public private partnerships (PPPs) in transportation infrastructure. The U.S. Department of Transportation has not updated its list of current and pending transportation PABs since January 23, 2017, but it includes $10.9 billion in specific projects, including these megparojects with PAB issuances over $500 million:

| State |

Project |

Million $ |

| VA |

I-66 HOT Lanes |

$946 |

| NY |

Moynihan Station |

$800 |

| CO |

I-70 East |

$725 |

| PA |

Rapid Bridge Replacement |

$721 |

| KY |

Ohio Bridge Crossing |

$676 |

| VA |

Elizabeth River Tunnels |

$675 |

| TX |

IH 635 Managed Lanes |

$615 |

| AK |

Knik Arm Crossing |

$600 |

| FL |

All Aboard Florida |

$600 |

| VA |

I-495 HOT Lanes |

$589 |

There was speculation that the decision to kill PABs came at the last minute, as Ways and Means staff were desperate to find revenue-raising provisions to keep the ten-year total cost of the bill below the $1.5 trillion maximum total mandated by the fiscal 2018 budget resolution. The JCT score of the bill estimates a total ten-year revenue loss of $1.487 trillion. This means that any amendment to remove section 3601 entirely would probably be ruled out of order by the chairman, since the loss of the $39 billion revenue-raiser would take the bill’s revenue loss above $1.5 trillion.

(Addendum: Friday afternoon, the Ways and Means Committee released a substitute version of H.R. 1 to be considered at next week’s markup. According to a summary from the Joint Committee on Taxation, none of the changes made in the new version of the bill affect the transportation-related provisions. The JCT score of the revised version lowers the 10-year deficit increase to $1.414 billion. However, the “on-budget” total (which excludes effects on the Social Security Trust Fund) may still be close to $1.5 trillion, and it is that total, we are told, which counts for purposes of qualifying the bill for fast-track budget reconciliation status.

Transportation and parking benefits. The House bill gets rid of a lot of deductible business expenses. Under current law, “transportation fringe benefits” (employer-provided parking, mass transit passes, and bicycle commute cost reimbursement) are currently tax-free both to employers (as a deductible business expense) and to employees (the dollar value of the benefits are excluded from their income tax calculation).

Section 3307 of the bill eliminates the employer’s ability to deduct the cost of transportation fringe benefits. If the employer chooses to continue the benefits, the benefits will still be tax-free to employees, but the fact that the benefits would no longer be a deductible business expense can be expected to diminish the willingness of employers to provide such benefits. (If the benefits are subject to the employee’s income tax total, then the employers can deduct the costs.) The JCT score estimated that the provision will increase tax receipts by $33.8 billion over the next decade.

The 2017 maximum amounts of transportation fringe benefits, per IRS Publication 15-B, are:

- $255 per month for combined commuter highway vehicle transportation and transit passes.

- $255 per month for qualified parking.

- For a calendar year, $20 multiplied by the number of qualified bicycle commuting months during that year for qualified bicycle commuting reimbursement of expenses incurred during the year.

The Ways and Means justification document says “The provision aligns the treatment of transportation fringe benefits, benefits in the form of on-premises gyms and other athletic facilities, and amenities provided to an employee that are primarily personal in nature and not directly related to a trade or business with other similar tax items.”

Meals for truck and bus drivers. The 50 percent deductibility of the cost of business meals continues, with an interesting gift for truck and bus drivers: the section also provides that “any expenses for food or beverages consumed while away from home (within the meaning of section 162(a)(2)) by an individual during, or incident to, the period of duty subject to the hours of service limitations of the Department of Transportation” would now be 80 percent deductible instead of 50 percent.

Electric cars. Section 1102 of the House bill repeals a number of existing tax credits, including the credit of up to $7,500 per vehicle for plug-in, electric-drive automobiles. Current law limits applicability of the credit to no more than 200,000 plug-in vehicles per manufacturer. The credit phases out over four calendar quarters beginning in the second calendar quarter following the quarter in which the manufacturer limit is reached. (The last IRS updated sales totals are here.)

The House bill would repeal the credit, effective for vehicles placed in service for tax years beginning after 2017. But the financial gain to the Treasury is small – estimated to be $3.8 billion over a decade.