The House Energy & Commerce Subcommittees on Environment and Climate Change, and on Consumer Protection and Commerce held a joint hearing Thursday, June 20 on efforts by the Trump administration to roll back the Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards.

History

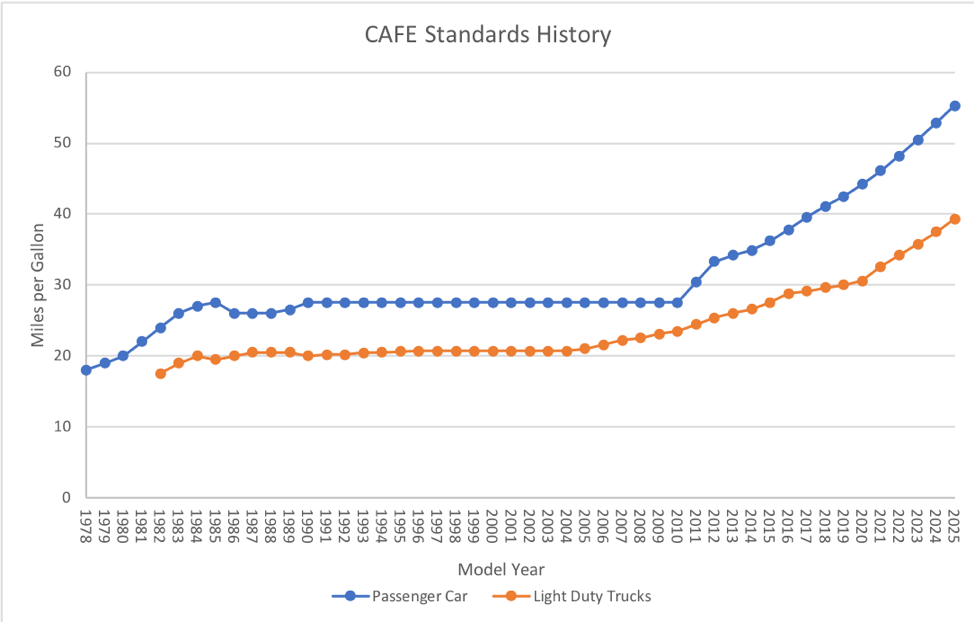

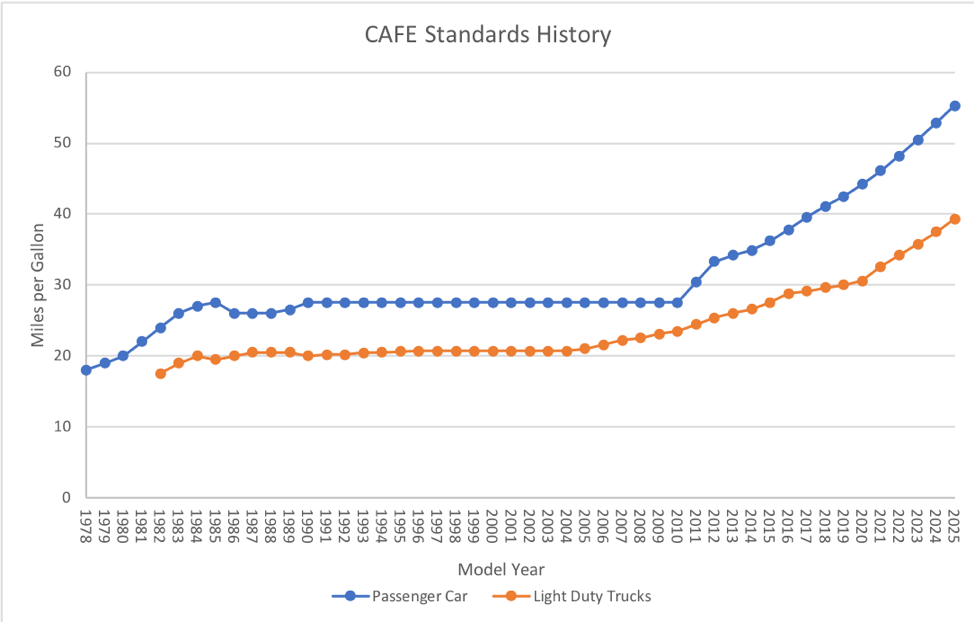

The CAFE standards were originally conceived as a way to lessen US dependence on foreign oil after the 1973 Oil Embargo. The CAFE standards were designed to improve fuel economy thus reducing the use of gasoline and became law in 1975. Between 1973 and 1983, fleet fuel efficiencies more than doubled, from 13.4 mpg to 27.5 mpg, surpassing the original passenger car standard of 18.0 mpg. The CAFE standards remained largely unchanged from the mid 1980s until their revitalization under the Obama administration. Changes to the CAFE standards have been seen as a response to large increases in the price of gasoline, such as after the 1973 oil embargo by the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries and the Iranian Revolution in 1979.

Source: National Highway Transportation Safety Agency (NHTSA), Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)

Current Issuesa

Claiming that the out-years of the Obama CAFE plan were unrealistic, EPA Administrator Andrew Wheeler said, “[m]ore realistic standards can save lives while continuing to improve the environment”. This is based off of the notion that reducing fuel standards will make newer cars cheaper and more accessible. Since newer cars generally have better quality safety equipment, lives will be spared. However, this is contrary to an Environmental Protection Agency analysis that shows reducing fuel standards would likely result in slightly more deaths due to lower driving costs inducing demand. While the Obama standards are high, approximately doubling from 2010 to 2025, there exist a number of alternative measures that automakers can implement to comply with the Obama CAFE standards, such as producing more hybrids or electric vehicles.

Also bundled in the CAFE standards rollback is the exemption waiver granted to California under the Clean Air Act (CAA). The waiver allows California to set its own emissions standards and in turn its own fuel economy standards. The revocation of the waiver would be an interesting move by an administration that proselytizes on States ability to self-regulate. Should the administration follow through with its proposed rule changes, California along with 17 others states and the District of Columbia plan to sue the EPA alleging it violates the CAA.

The hearing was split into two panels. The first called only two witnesses, EPA Assistant Administrator William Wehrum and US Department of Transportation Deputy Administrator of NHTSA Heidi King. Before the hearing began, EPA Administrator Andrew Wheeler released a letter, chastising Mary Nichols of the California Air Resources Board (CARB), for failing to negotiate in good faith regarding a potential compromise before talks broke down earlier this year. The exclusion of Nichols from the first panel caused some bickering between Representatives John Shimkus (R-IL), Frank Pallone (D-NJ), and Greg Walden (R-OR) over whether there was precedent for having a state official on a federal witness panel. This minor exchange set the tone for an often contentious hearing.

Wehrum and King were on the defensive for much of the hearing, attempting to justify the rational and underlying analysis that led the administration to propose the rollback. King maintained that, “consumers are less likely to replace their older, less safe car with a newer, safer car if that newer, safer car is 20 percent more expensive”, and used this rationale to justify the purported safety benefits of the rollback.

When pressed on issues of how the rule change would impact climate change, by Rep. Jerry McNerney (D-CA) Wheeler was non committal stating only, “I regulate greenhouse gases everyday.” McNerney challenged him on not directly answering the question and eventually digressed.

Much of the testimony was framed as rural interests against California. During her time, Rep. Debbie Dingell (D-MI) called for a renewed attempt to negotiate with California to fulfill the goal of one national standard. Dingell said she fears that without California’s involvement the entire process would end up in litigation for years to come, almost assuredly harming the many auto workers who are her constituents. For Dingell she was, “really not interested in a pissing contest between California and this administration, to be perfectly blunt.” Both King and Wehrum were skeptical of the idea of California returning to the negotiating table, with King insinuating that it is too late in the process now and Wehrum pointing to Administrator Wheeler’s letter.

The second panel brought together a collection of interested parties; Mary Nichols of CARB, David Freidman of Consumer Reports, Ramzi Hermiz of Shiloh Industries, Josh Nassar of United Auto Workers, Shoshana Lew from the Colorado DOT, Louisiana Attorney General Jeff Landry, David Schwietert for the Alliance of Automobile Manufacturers, and Nick Loris of the Heritage Foundation.

Nichols was the critical witness of the second panel, often simultaneously defending California’s need for special consideration in regard to fuel standards and CARB’s role in the failed negotiation. Nichols began her remarks by eschewing the majority of her written statement, instead using her time to vehemently refute the claims in Wheeler’s letter, which she found out about shortly before the hearing through media reports, by focusing on one key paragraph in her prepared remarks. “Each time the Trump Administration has been unwilling to find a way that works, their claim that California offered no counter proposal is false. They unilaterally decided to cut off communications”, said Nichols adding that she stood by “every single word of that paragraph.”

When pressed by lawmakers on whether California is committed to a single national standard, Nichols maintained that, “[w]e want a national standard, we don’t want to destroy the interstate commerce clause”. She went further when responding to questions by Dingell, stating “[w]e have always been prepared to go to the negotiating table in good faith and we still are.”

Of note towards the end of the second panel was an exploration into the various proposed alternatives. While it was stated that no alternative proposed in the Safer Affordable Fuel Efficient Vehicle (SAFE) program has been decided upon, remarks by the first panel insinuated that the zero growth rule was the preferred alternative of the administration. This was in contrast to the majority of stakeholders on the panel, and many of the law makers, who urged for a compromise. Hermiz pointed to alternatives 6 and 8 as starting points for compromise and a level that automakers could feasibly meet.

Nassar concurred with Hermiz on the need to set standards that increase each year as a way to continue to spur innovation. Nassar was particularly concerned with the potential for litigation and the snowball effect it would have on the auto industry. “We should all work towards a single National Program. Any proposed changes to emissions standards that result in a bifurcated market or a protracted legal battle will make regulatory compliance burdensome and create uncertainty, both of which will discourage investments in the U.S. auto industry.”

A final rule on CAFE and SAFE is likely to be decided upon soon, though it is inevitably going to lead to a protracted legal battle. Barring a sudden change in course that reopens negotiations with California, the worst case scenario of regulatory uncertainty for auto workers and manufacturers seems likely.