January 19, 2018

This week, the House Rules Committee held a set of hearings to examine whether or not Congress should resume earmarking funds for specific projects. A January 17 hearing featured testimony from Members of the House, and a follow-up hearing on January 18 featured testimony from outside groups.

(ETW’s Jeff Davis submitted testimony for the hearing record – see here.)

Interest in earmarking is now higher than it has been since Republicans took back the House in 2011 and announced that they would refuse to bring bills containing earmarks to the House or Senate floor. There are three big reasons why the interest in earmarking is peaking now, all of which have to do with President Trump.

Infrastructure plan. Sometime around the State of the Union Address at the end of the month, President Trump will submit his infrastructure plan to Congress and will make it a major legislative priority of 2018. By all accounts, the plan would include tens of billions of dollars in funding for discretionary grant programs where federal agencies would evaluate and select projects.

After Congress got rid of its own earmarks in 2011, they also took steps to take away the ability of executive branch agencies to pick its own projects. (The 2012 MAP-21 law got rid of most such discretionary programs funded through the Highway Trust Fund.) While one large new discretionary grant program (FASTLANE/INFRA) was created in the 2015 FAST Act, the prevailing spirit in Congress is still very much “if we can’t pick projects, the President shouldn’t be able to, either.”

Program stalemate. There are several existing programs – the Federal Transit Administration’s “Capital Investment Grant” program, for example – where the authors of the statute authorizing the program clearly did not anticipate that a President would want to just shut the program down. For programs like CIG, Congress’s self-imposed earmark plan is a major roadblock that could prevent Congress from ordering the Administration to proceed with projects that have long been in the pipeline and are anticipating imminent federal funding.

A matter of trust. At the end of the day, most earmarks are about a lack of trust. A member of Congress just doesn’t trust the executive branch to give his/her district a “fair share” of funding distributions for a discretionary program. Or, for formula programs, the member of Congress does not trust his/her state government or local government to pick the right projects for their district.

The national political scene is beyond the scope of ETW, but anyone can see that trust between Congress and the White House is now at an all-time low. To the extent that Congressional earmarking is a symptom of distrust between the branches, one can easily see why the demand for bringing earmarks back is so strong.

Herewith, two examples of how earmarking revolves around trust or a lack thereof.

- In spring 1997, as his Transportation and Infrastructure Committee was preparing to draft the surface transportation reauthorization bill, chairman Bud Shuster (R-PA) and a few staffers went to the State Capitol in Harrisburg, PA and met with Governor Tom Ridge and PennDOT Secretary Brad Mallory. Shuster and Ridge had served together in the House for years and were good friends. More important, there was a high level of trust between the two men. At that meeting, the two men struck a handshake deal – if Shuster was able to enact a law that increased the Keystone State’s take of highway formula funding by x amount, then Ridge guaranteed that PennDOT would spend at least y amount of the formula money on a secret list of projects in Shuster’s district. (Shuster also got $112 million in earmarks in the final TEA21 law, because it would have looked odd if he hadn’t, but his real take from the bill was much higher because of his handshake deal with Gov. Ridge.)

- Ten years later, after Democrats took back Congress in the 2006 elections, incoming House Appropriations chairman Dave Obey (D-WI) decided to finish out the incomplete fiscal 2007 appropriations process under a continuing resolution instead of an omnibus bill, which meant that 2007 would be a year without earmarks. Instead of dividing up the $850 million in discretionary highway and bus money amongst dozens or hundreds of projects, as Congress would have done via earmarking, the U.S. Department of Transportation consolidated all of the money into an incentive grant program called “Urban Partnership Agreements” and put it all in just five cities (Miami, Minneapolis, New York City, San Francisco and Seattle) – and the NYC money was made contingent on the state legislature approving Mayor Bloomberg’s controversial plan for imposing congestion pricing in Manhattan. Congress pushed back and took earmarking even wider in 2008. The way in which the Obama Administration handled many of its own discretionary project allocations later on was viewed by Republicans as overly politicized, which further encouraged the GOP to shut off discretionary programs in 2012.

The members-only hearing at Rules revealed a strong appetite for bringing back earmarks, but the outside witness panel was generally against it. (The witness list called by chairman Pete Sessions (R-TX) appeared stacked against earmarks – Taxpayers for Common Sense, Citizens Against Government Waste, and Texans for Fiscal Responsibility all predictably opposed earmarks, the Bipartisan Policy Center supported them, and Texas DOT was more neutral.)

(Ed. Note: The Texans for Fiscal Responsibility written testimony was remarkably blunt to the point of being rude.)

(Further Ed. Note: There have been recorded instances of earmarks actually saving taxpayer money. Not often, but it does happen. The fiscal 2005 Labor-HHS-Education appropriations bill is a case in point. The bill did not have the votes to pass the House because it cut billions of dollars from popular social programs. The bill was pulled from the floor and a few targeted earmarks were added to buy the votes of just enough legislators to pass the bill.)

The return of earmarks still faces an uphill fight, in part because anyone who was around the last time that Congress used earmarks remembers the excesses that led to their banishment.

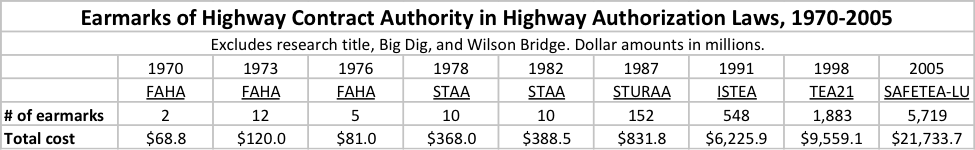

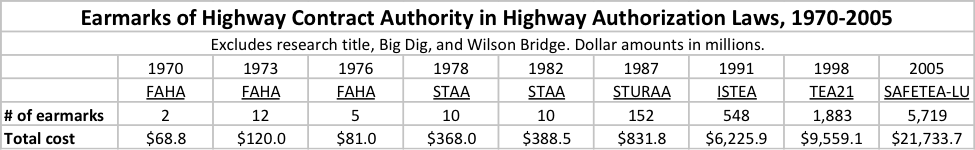

The 2005 SAFETEA-LU law, as much as anything else, killed the earmarking process. It earmarked so widely (and, in some cases, so embarrassingly) that it brought the entire federal-aid highway program and the concept of earmarking in general into public disrepute. (See this study that traced the biggest earmarks back to their sponsors.)

- The “Bridge to Nowhere” between Ketchikan, Alaska (population: about 8,000) and Gravina Island (population: 50) got $223 million in earmarks in SAFETEA-LU from T&I chairman Don Young (R-AK). The benefit to cost ratio of the project was so absurdly negative that it was apparent to the average person on the street, which is why it was the first earmark to be featured on the cover of PARADE magazine (and not in a good way).

- Former House Speaker Dennis Hastert (R-IL) recently got out of federal prison after seeing a 13-month term. The crime for which he was convicted was a bank fraud technicality relating to his paying $1.7 million in hush money to cover up a much worse crime he had committed so long ago that the statute of limitations had expired. For those asking “how did a retired civil servant have $1.7 million laying around to spend on hush money,” the answer is that Hastert got $557 million in highway earmarks in the 2005 SAFETEA-LU law, and the enactment of one of those earmarks allowed Hastert to make a $3 million profit on a land deal he kept secret at the time. (See this 2015 Washington Post story for the details.)

- And the earmarking did not stop after the House and Senate passed the bill. The House staff later ordered the House Enrolling Clerk to make a correction in the final bill to be sent to the President’s desk to add a new earmark they had inadvertently left out (Coconut Road near Naples, Florida), which arguably violated the Constitution. When this later came to light, the Senate actually voted, 64 to 28, to ask the Justice Department to investigate the House earmark, something that had never happened before.

When coupled with the 2005 bribes-for-earmarks scandal that sent Rep. Duke Cunningham (R-CA) to federal prison for eight years, Congress was forced to enact ethics reform legislation that also included the first transparency requirements for earmarks. Henceforth, Congress was forbidden from considering legislation containing earmarks unless the identity of the earmark sponsors was made public.

However, the earmark disclosure rules (which are still on the books – the earmark ban is not written into House or Senate rules but is an internal policy of the Republican Conference in each chamber) have some loopholes, which are discussed in the companion piece “8 Ways to Improve the Earmarking Process.” Foremost among these is something that became obvious from the Hastert and Coconut Road earmarks: real estate developers are a big part of the problem.

Nothing in the existing rules requires the identity of real estate interests who would profit from an earmarked infrastructure project through or near their land to be made public. If Speaker Hastert’s ownership of the land adjacent to the Prairie Parkway had been publicly known at the time, the earmark would faced real scrutiny (and you can be sure that President Bush would not have singled it out for praise in his remarks at the bill signing). Likewise, the political donations around the Coconut Road earmark came from the real estate developers who stood to profit from the project, but this was not discovered until several years later.

The absence of any disclosure rules for real estate interests that would profit from earmarks is extra ironic given that the President of the United States at the moment is a real estate developer with a history of seeking federal earmarks for infrastructure that would benefit his projects. (See this 2015 ETW Article, “Trump City: The Earmark that Changed the Rules” for more information.)

Real estate profit from the installation of infrastructure is so great that there has been a move to try to get those real estate interests to help pay for the costs of the infrastructure. This idea, called “value capture,” is farthest developed in mass transit. The Transit Cooperative Research Board published a summary report on current value capture techniques a year ago. But some those principles could also be applied to highway projects. For example, tax increment financing. If a new road or interchange will increase the value of the adjoining real estate, forever, then the locality could pledge, in advance, the increased property taxes stemming from the increased real estate value over the coming decades to pay back the debt issued to build the new road or interchange.

Value capture is harder to do at the federal and state levels because so much of value capture it relates to property taxes, which are held sacrosanct as the prime revenue source for local government. But a requirement that local value capture be used wherever possible could accompany any future earmarks and would serve to force real estate developers to pay for some of the benefits that targeted infrastructure projects give them.