May 30, 2018 – revised May 31, 2o18

Last Friday afternoon, the House Rules Committee announced the amendment process by which the Water Resources Development Act (H.R. 8) will be brought before the House of Representatives for debate next week. That process includes stripping out a provision authored by Rep. Peter DeFazio (D-OR) that would have made tens of billions of dollars from the Harbor Maintenance Trust Fund (HMTF) available for immediate expenditure – ten years from now.

H.R. 8 as introduced on May 8 by DeFazio and House Transportation and Infrastructure chairman Bill Shuster (R-PA) included, in section 102, a provision long sought by DeFazio making all HMTF funding available for expenditure “without further appropriation, for fiscal year 2029 and each fiscal year thereafter.” FY 2029 begins on October 1, 2028, so all HMTF balances would immediately be made available as mandatory budget authority on that date.

The Congressional Budget Office only scores the spending and revenue impact of legislation on a ten-year timeframe, and for legislation being considered this year, that ten-year window ends on September 30, 2028 – which, of course, is why DeFazio selected that date.

Upon the request of the chairmen of the House Budget Committee and the House Appropriations Committee, the Rules Committee dispensed with the text of H.R. 8 as amended by the T&I Committee and is instead making in order a new print of the text from which section 102 has been stricken and subsequent sections renumbered. House members seeking to amend H.R. 8 must file amendments to the revised print by noon on May 31. (May 31 addition: 81 amendments to H.R. 8 were filed by the deadline, and they can all be found here.)

For his part, DeFazio’s staff told CQ today that he intends to file an amendment to H.R. 8 that would reinstate his HMTF provision – but Rules, having stripped out the provision in the first place, almost certainly won’t allow DeFazio to offer such an amendment. There will be one opportunity for DeFazio to offer an amendment of his choice at the end of debate (a “motion to recommit” the bill), but that amendment has to obey all budget rules and laws, and his HMTF amendment likely violates at least one of the multitude of those.

(May 31 addition: One of those amendments filed, by DeFazio and Shuster, tries a different procedural tack from the earlier provision and would also increase overall HMTF spending. The text is here and see analysis below.)

If all of this sounds familiar, it is because it happened two years ago. T&I reported a WRDA bill with the DeFazio ten-year-delayed HMTF spending provision and Rules stripped it from the bill, inspiring DeFazio to vote against the bill on final passage (see this article for more information). DeFazio at that time did not offer his HMTF amendment as the motion to recommit.

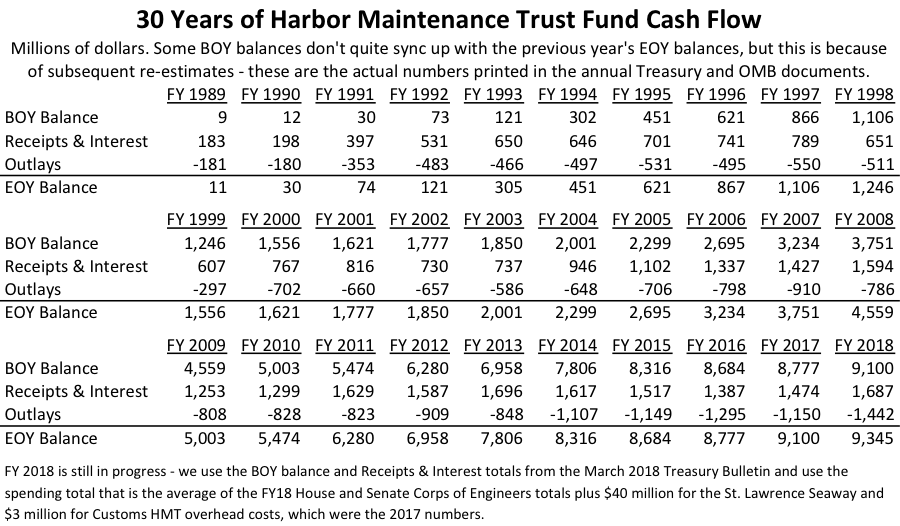

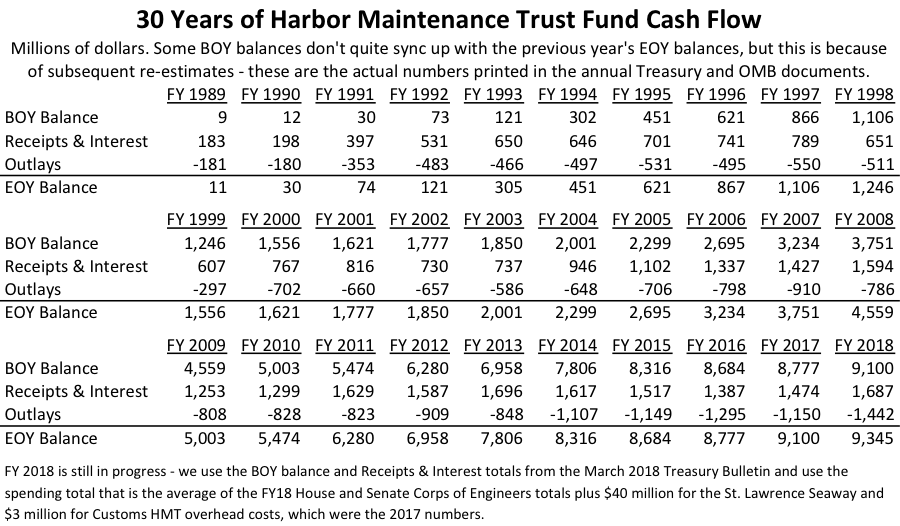

But even though jurisdictional opposition from the Budget Committee and the Appropriations Committee will once again prevent DeFazio from forcing a House vote on a spend-down of HMTF balances, his underlying point is still accurate – Congress has allowed balances in the HMTF to build up to the point that the relationship between tax receipts and spending levels in what is supposed to be a “user-pay” trust fund system is broken. Here are the last thirty years worth of HMTF cash flow:

If the HMTF ends up 2018 with a balance of about $9.3 billion, that will be about six-and-a-half years worth of spending at the newly increased spending level of $1.4 billion per year.

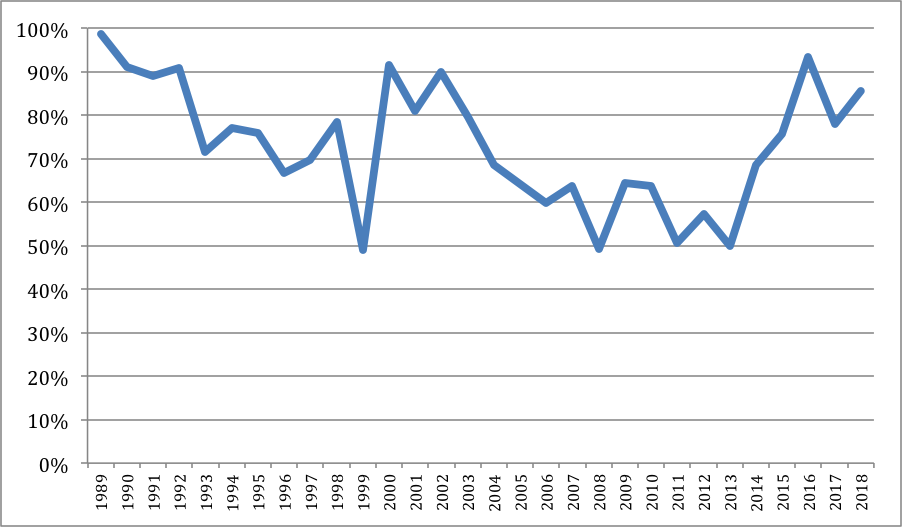

Taking the above data and visualizing it, the relationship between annual receipts (and interest) versus annual spending is shown in the following chart, which simply divides annual outlays by annual receipts and interest. 100 percent means the two numbers are the same, a number higher than 100 percent means that the HMTF spent more than it brought in that year, and a number lower than 100 percent means that the HMTF brought in more than it spent.

The statutory caps on discretionary spending first put in place in FY 1991 are indifferent to the source from which an appropriation is drawn – it doesn’t matter whether the money is drawn from a user-supported trust fund with a hefty balance or from general fund borrowing from the international bond market. A discretionary dollar is a discretionary dollar, they are all fungible (within the defense and non-defense categories), and they all count towards the same cap.

The 2014 WRRDA law established targets for the Appropriations Committees to hit for annual HMTF appropriations levels, and those targets have been met, which has led to the rising trend in the above graph in the last few years (the spike in 2016 was about lower-than-expected tax receipts). But those targets never get close to 100 percent of new tax receipts, and thus can never begin to spend down the built-up trust fund balances.

DeFazio’s original answer was, in effect, to get around the spending caps by making excess HMTF balances into mandatory spending, not discretionary appropriations. But it is extremely difficult to take an existing program from one spending category to another. (The veterans bill that the President is about to sign into law this week effectively does that for one veterans health program – see Nita Lowey’s (D-NY) amendment to the first appropriations “minibus” appropriations package for 2019 to amend the spending caps to account for that change.)

(May 31 addition: The new DeFazio-Shuster amendment tries a different way to get around the spending caps. It increases the annual amount of the non-defense spending cap each year by the amount of HMTF appropriations, ensuring that those dollars are no longer fungible with the rest of the non-defense budget and removing any fiscal motivation for the Appropriations Committees not to provide the money. However, to ensure that the amendment does not result in the appropriators spending the extra money all at once, the amount of HMTF appropriations that would no longer count towards the spending caps each year is limited to the actual amount of receipts and interest from the most recently completed fiscal year. For the FY 2019 spending bills being drafted by Congress now, for example, the cap adjustment would be limited to the FY 2017 receipt and interest total of $1.474 billion. Appropriators could provide money in addition to that, but it would count towards the spending caps.

This new amendment is likely to meet the same fate as the first – it clearly invades the jurisdiction of the Budget Committee, and will likely be opposed by that chairman. The Rules Committee is known as the “Speaker’s Committee,” and the current Speaker used to be Budget Committee chairman. But the new amendment is a more measured way to address the ongoing HMTF problem than was the original approach.)

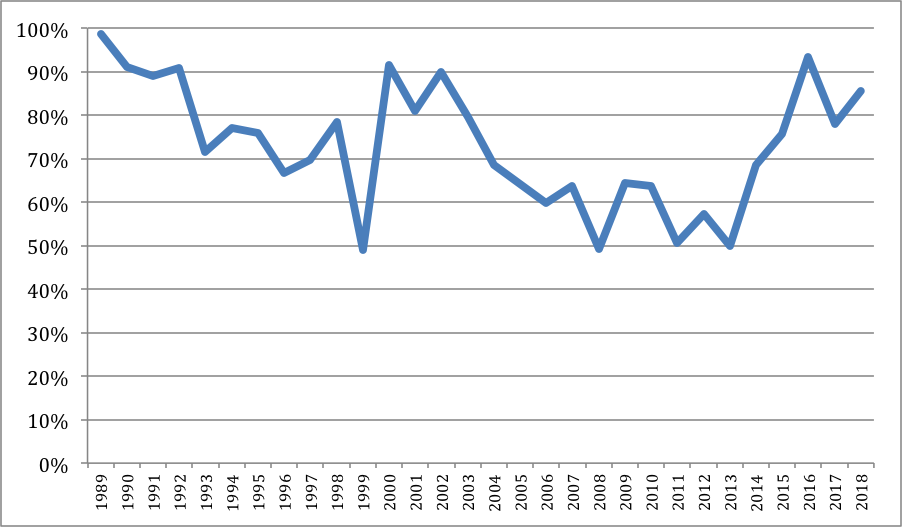

The above information shows that, from a user-pays perspective, the Harbor Maintenance Trust Fund is effectively broken. And everything that ETW and its predecessor publication have been reporting on for the last decade reinforces that the Highway Trust Fund’s (HTF) user-pay model is also broken, just in the opposite direction.

Congress has proven itself incapable of keeping HMTF spending levels up near the level of annual tax receipts or else cutting user taxes to match the lower spending levels. And Congress has proven itself incapable of restraining HTF spending levels to anywhere near the level of annual user tax receipts or else reducing the user taxes down to the spending level.

Of the three major user-supported transportation trust funds, only the Airport and Airway Trust Fund (AATF) has maintained a reasonable relationship between spending and taxes, making sure that the trust fund never comes close to default while at the same time preventing excessive balances from building up.

This may be because the AATF has a mandatory spending component (airport grants) as well as the discretionary program, and also because FAA operational expenses have always received some general fund support to reflect that safety regulation, military use of airspace, etc. are common goods and not user-financed. The Appropriations Committees each year can vary the general fund to trust fund ratio for FAA spending to make sure that the trust fund stays on a sustainable course.

The following chart shows, for the last twenty years, the outlay to receipt/interest ratio for the three major transportation trust funds. The HMTF information is from the above chart, and as you can expect, the HTF trend line is the opposite. Only the AATF trend line keeps dancing around the tax receipt level.