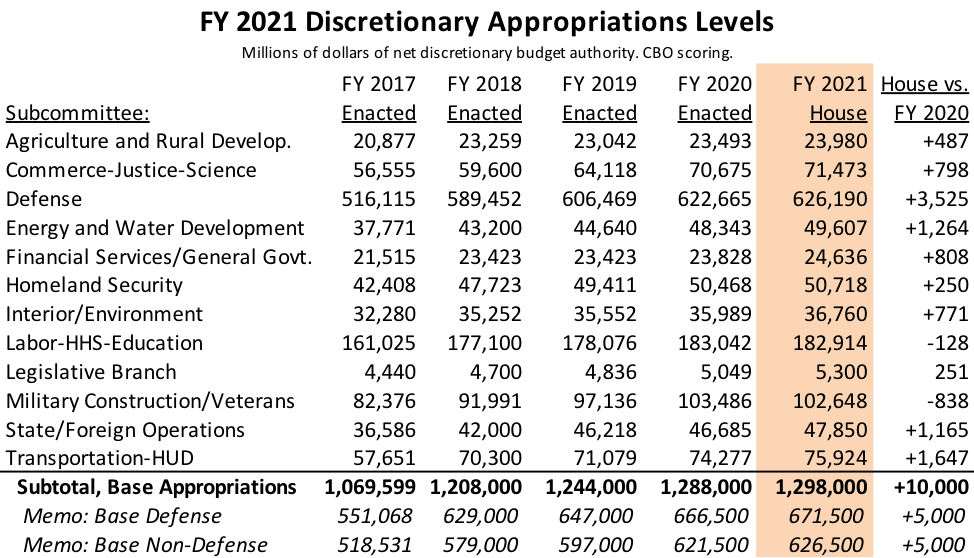

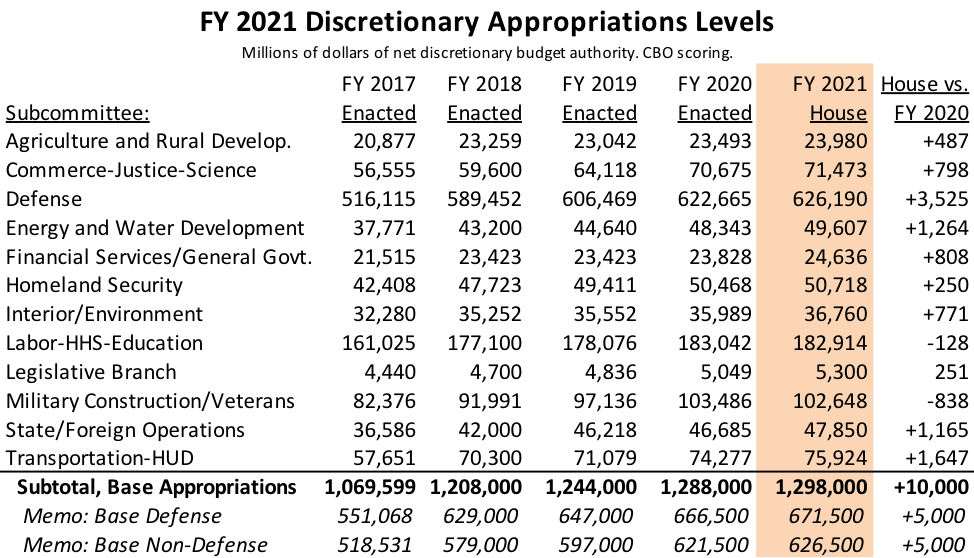

House Democrats this week unveiled their outline for the twelve bills that would fund the discretionary side of the federal government for fiscal year 2021. The spending outline adheres to the Budget Control Act spending caps totaling $1.298 trillion, set in the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2019, but only by funding many Democratic priorities as off-budget emergencies, which require a Senate supermajority and Presidential approval, sometimes line-item by line-item, in order to be successful.

$1.298 trillion in base funding. The House Appropriations Committee is scheduled to adopt chairman Nita Lowey’s (D-NY) plan to subdivide nearly $1.3 trillion in discretionary funding amongst the twelve subcommittees at a markup on July 9 according to the following plan:

While the Transportation-HUD Subcommittee was one of the winners and got a $1.65 billion increase, only $78 million of that net increase went to the Department of Transportation (HUD got $1.5 billion of the increase).

But the regular budget, prepared under fairly tight spending constraints, is only a part of the whole.

Plus emergencies. The House plan would supplement the $1.298 trillion in “base” appropriations with an additional $247.6 billion in appropriations that would not be subject to the spending caps because they would be designated an “emergency,” making them effectively off-budget. The totals are shown below, in millions of dollars.

|

Regular |

Emergency |

|

(Subject to |

(Exempt |

|

BCA Caps) |

from Caps) |

| Agriculture and Rural Develop. |

23,980 |

0 |

| Commerce-Justice-Science |

71,473 |

0 |

| Defense |

626,190 |

0 |

| Energy and Water Development |

49,607 |

43,500 |

| Financial Services/General Govt. |

24,636 |

67,183 |

| Homeland Security |

50,718 |

0 |

| Interior/Environment |

36,760 |

15,000 |

| Labor-HHS-Education |

182,914 |

24,425 |

| Legislative Branch |

5,300 |

0 |

| Military Construction/Veterans |

102,648 |

12,494 |

| State/Foreign Operations |

47,850 |

10,019 |

| Transportation-HUD |

75,924 |

75,000 |

| TOTAL |

1,298,000 |

247,620 |

Congress enacts billions of dollars of emergency appropriations each year. In fiscal 2017, Congress appropriated $19.4 billion in emergency spending. This rose to $125.6 billion in fiscal 2018 because of the damage done by the Harvey-Irma-Maria 2017 hurricane season (plus wildfires in the West), then it dropped back down to a more normal $25.4 billion in fiscal 2019. Because of coronavirus, Congress is in the process of blowing out the emergency designation in fiscal 2020 – $511.4 billion in emergency appropriations to date, with almost three months still to go in the fiscal year to enact even more funding. (By comparison, the emergency appropriations in the 2009 ARRA stimulus bill only totaled $311 billion.)

But the “emergencies” funded by the House’s 2021 bills under that designation are different from rebuilding after hurricanes, floods and wildfires, or responding to once-in-a-century pandemics and the unique economic circumstances that come with that. The $12.5 billion in emergency funding in the Military Construction-VA bill largely converts advance appropriations for veterans health care (provided last year but becoming available on October 1, 2021) from regular to emergency. This was widely criticized by Republicans in this week’s markup as a “gimmick” to make it look like the regular budget for that subcommittee was dropping, when in fact the regular program is increasing. The White House has so far refused to carve out an exemption from the caps for certain kinds of veterans health funding, as has been proposed by Senate appropriators on a bipartisan basis, and efforts to get such a cap exemption in the bipartisan budget agreement last year failed.

And and the rest of the emergency funding is for infrastructure, across the Energy and Water (water infrastructure, power grid, clean energy research), Financial Services (FCC broadband), Interior/Environment (water supply), Labor-HHS-Education (health and hospital research), and Transportation-HUD bills. This funding is largely consistent with the authorization targets made by the Democratic infrastructure bill passed by the House last week (H.R. 2).

Where is the dividing line between regular funding and emergency funding?

Fortunately, these terms are precisely defined in section 250 of the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act of 1985, as amended (the Gramm-Rudman-Hollings Act). In order to qualify as an “emergency,” the following conditions need to exist:

§250(c)(20) The term ‘‘emergency’’ means a situation that—

(A) requires new budget authority and outlays (or new budget authority and the outlays flowing therefrom) for the prevention or mitigation of, or response to, loss of life or property, or a threat to national security; and

(B) is unanticipated.

Obviously, the “unanticipated” part is key, so the law then goes on to define, in detail, what that word means in this context:

§250(c)(21) The term ‘‘unanticipated’’ means that the underlying situation is—

(A) sudden, which means quickly coming into being or not building up over time;

(B) urgent, which means a pressing and compelling need requiring immediate action;

(C) unforeseen, which means not predicted or anticipated as an emerging need; and

(D) temporary, which means not of a permanent duration.

The need for additional federal investment in infrastructure may be urgent, but it is hardly “sudden” – this problem has been building up for decades. And to call the infrastructure problem “unforeseen” is ludicrous – at the very least, we all saw the problem coming at Infrastructure Week every year going back almost a decade. Likewise with the Military Construction-VA bill’s designation of $12.5 billion of veterans health funding as an emergency – the problem was clearly foreseen when Congress enacted, and the President signed, a law in 2018 creating a new unfunded health program and stuck the Appropriations Committees with a rapidly growing bill. (It is a big and real problem, but not in the least “unforeseen.”)

Budget law makes it hard for the emergency designation to be used unless there is broad political support. In the Senate, any Senator can make a point of order under section 314(e) of the Budget Act and knock an emergency designation out of a paragraph unless at least 60 Senators vote to approve the designation. And even if Congress passes a law with a bunch of emergency designations, the President has effective line-item veto power over these – budget law says that each individual account must have a separate emergency designation, and once the bill is signed into law, if the President does not then sign an approval of the emergency designation for each account and transmit it to Congress, those appropriations count towards the spending caps. (See here for POTUS’s emergency designation of each emergency account in the CARES Act.)

Of the seven House bills that provide emergency funding, six have a catchall proviso in the back of the bill (sec. 607 of Energy & Water, sec.901 of Financial Services, sec. 501 of Interior, sec. 603 of Labor-HHS, sec. 514 of MilCon and sec. 8008 of State/Foreign) that ties all of the sundry emergency designations in the bill together so the President has to take or leave all of the designations in that bill – and so that the funding only becomes “available” (a.k.a. spendable) if the President signs a designation:

Each amount designated in this Act by the Congress as being for an emergency requirement pursuant to section 251(b)(2)(A)(i) of the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act of 1985 shall be available (or rescinded or transferred, if applicable) only if the President subsequently so designates all such amounts and transmits such designations to the Congress.

But the Transportation-HUD bill, as approved by subcommittee, does not have such a proviso tying all the emergency designations together, which would give the President the authority to pick and chose which would be exempt from sequestration and which would not (if he chose not to exempt some of them).

In any event, for the emergency appropriations not to trigger another round of sequestration, 60 votes in the Senate and Presidential approval of the emergency designation, even if he accepts the non-emergency parts of the bill, are required. At least for fiscal 2021.

Wait until next year for infrastructure? The Budget Control Act’s caps on discretionary spending are set to expire after fiscal 2021. After that, unless the caps are extended, in fiscal 2022, Congress and the President will be able to appropriate as much money as they want, whether or not it is designated as an emergency or an Overseas Contingency Operation or something else, without having to worry about triggering another round of across-the-board sequestration.

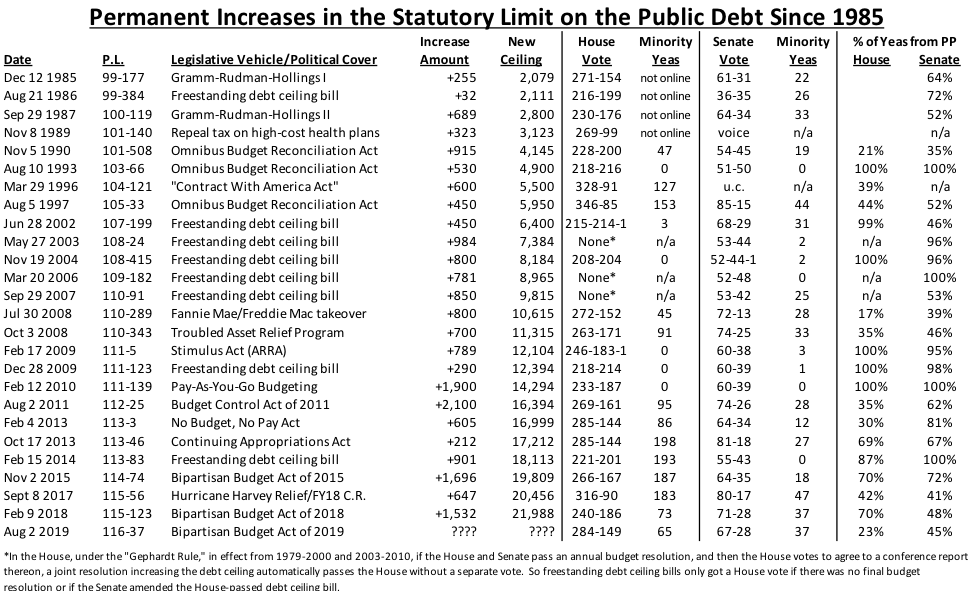

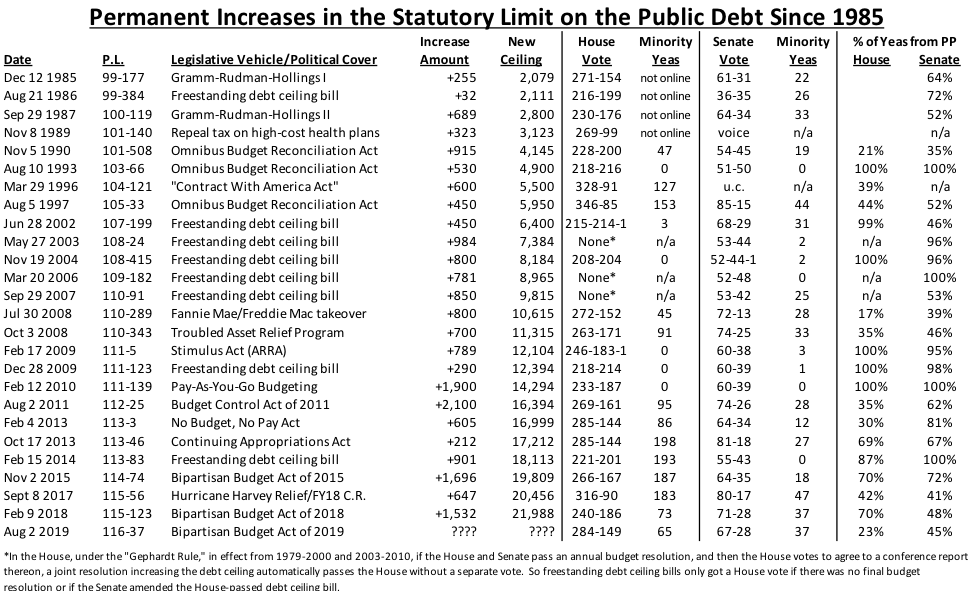

Would Congress extend the caps? Maybe. Spending caps were originally imposed by the fall 1990 bipartisan budget deal, then allowed to lapse in 2002. They were reinstituted in August 2011 as part of the deal to get the federal debt limit increased.

As fate would have it, the federal government is currently operating without a debt limit (or, rather, the debt limit of $21.988 trillion has been suspended since the enactment of the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2019 – but a new debt limit will come into being at midnight on July 31, 2021, at whatever the amount of the debt is at that point). As of close of business yesterday, the debt subject to limit was $26.434 trillion, meaning that the federal government has borrowed $4.4 trillion in 11 months.

By August 2021, the amount of debt incurred may finally be enough to scare some members of Congress. Raising the debt ceiling is always a tough proposition in which the minority party in Congress usually sits on its hands and makes the majority do all the work. Once a new debt limit pops into being 13 months from now, the Treasury can avoid crisis for two or three months via “extraordinary measures” like taking money from off-budget retirement funds and moving money around with the Federal Reserve, but at some point in fall 2021, a change in law will be necessary to increase the debt limit or the government will start shutting down.

Raising the debt limit is a big lift for Congress – over the last decade it has almost had to be tied into some kind of larger fiscal package as some kind of “cover vote” or sweetener. The closer we get to fall 2021, the more likely it is that any major fiscal action by Congress – whether that is to extend constraints on spending, or passing a large amount of new, not-a-true-emergency spending without constraint (like a big infrastructure bill) will get wrapped up in the talks about the debt limit.