Perhaps the most revolutionary thing about the transportation portions of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) was its emphasis on distributing funds via competitive grant programs in lieu of more traditional formula-based transportation funding. Of the $567 billion provided in the law for the U.S. Department of Transportation, we estimated some $122 billion, or 21 percent, took the form of competitive grants.

This week, the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee held a hearing to examine stakeholder perspectives on these competitive grant programs. The March 7 full committee hearing featured testimony from a state DOT, an MPO, a county government, and the trade association representing smaller railroads:

- Hon. Alan Winders, Presiding Commissioner, Audrain County, Missouri, on behalf of National Association of Counties | Witness Testimony

- Mr. Chuck Baker, President, American Short Line and Regional Railroad Association | Witness Testimony

- Ms. Amy O’Leary, Executive Director, Southeast Michigan Council of Governments | Witness Testimony

- Hon. Jared W. Perdue, P.E., Secretary, Florida Department of Transportation | Witness Testimony

City and county governments have long chafed at the traditional way of distributing federal dollars, which was to give the money to state governments and put the state in charge of distributing the money at the sub-state level. The creation of the federal mass transit aid program in 1964 was notable because in transit, the federal dollars usually flow directly to the locality, bypassing the state coffers, and this was done because many big cities in the 1950s and 1960s did not trust their rural-dominated state governments. The new emphasis on competitive grant agreements in the IIJA was seen as a way to bypass states in many instances and to empower local governments.

(Ed. Note: Much of this tension is inevitable. For proof, pull up the text of the U.S. Constitution in your browser, then do a [Ctrl]-F search for the word “State.” Compare the number of times that the word “State” appears in the Constitution versus the number of times that words like “city,” “county,” “town,” “local,” “municipal,” etc. appear. For whatever reasons, the Founders just did not envision the federal government having any kind of direct relationship with sub-state levels of government, which has put cities and counties at a perpetual disadvantage when asking for federal largesse.)

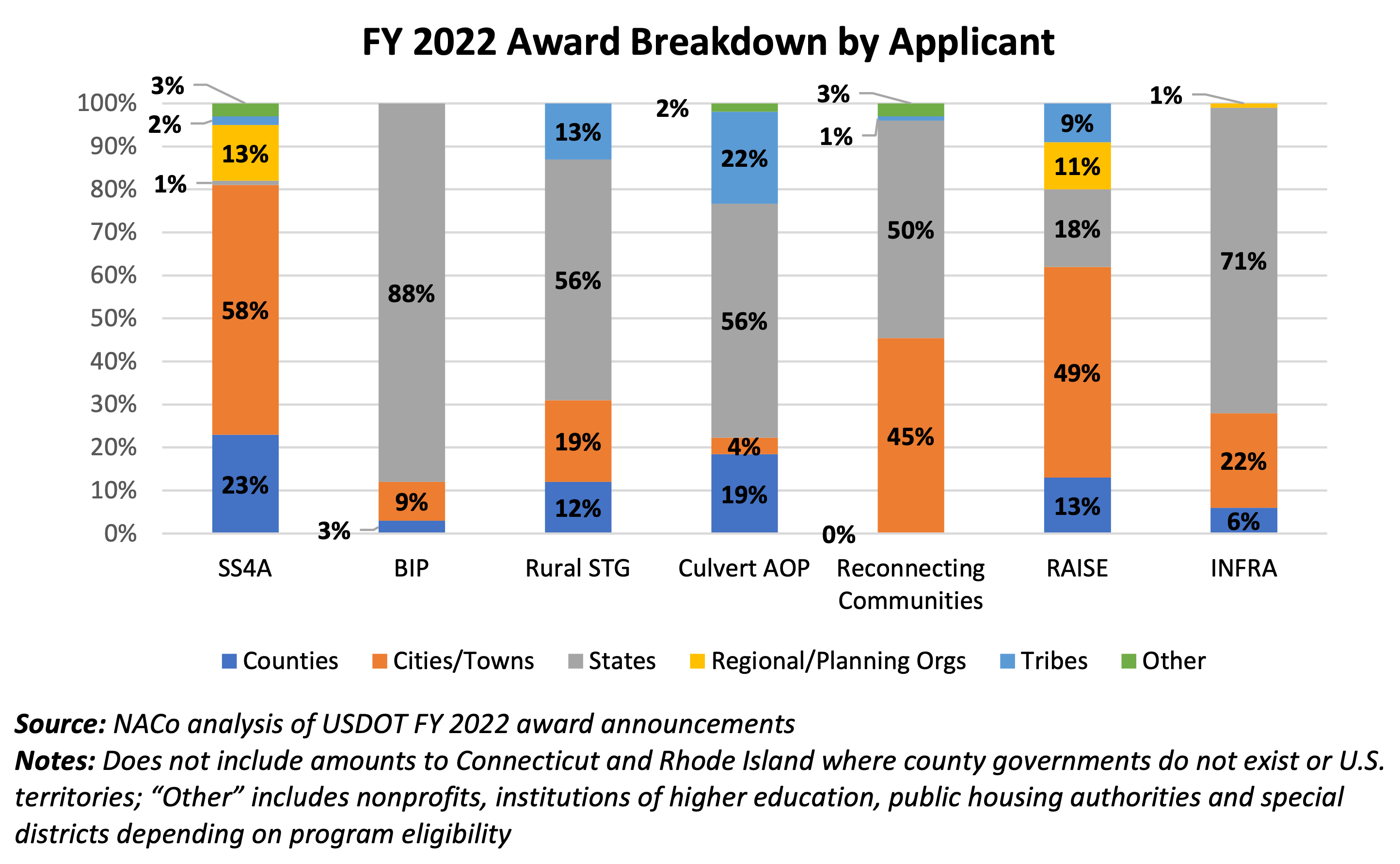

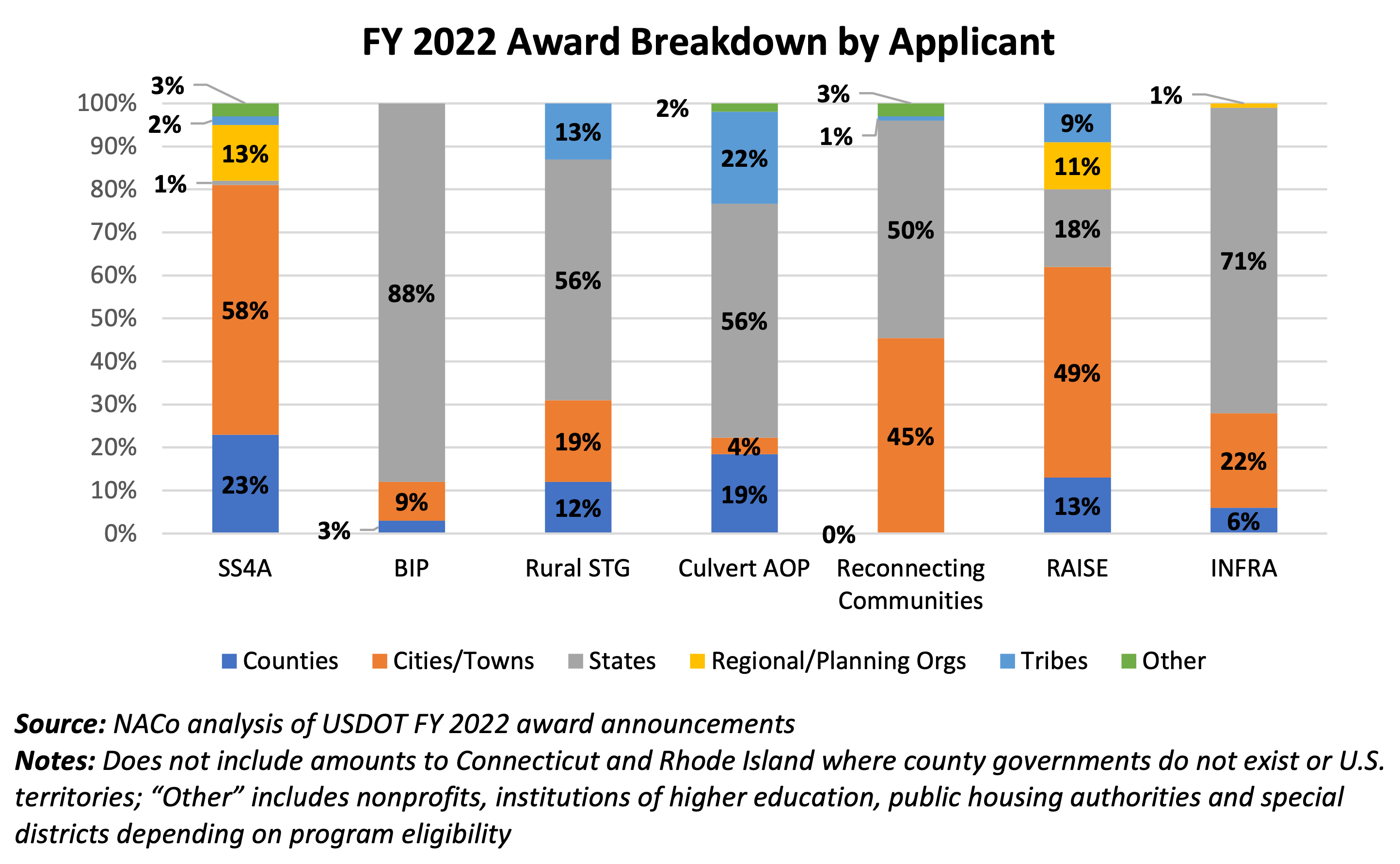

The NaCo testimony included a good chart breaking down certain fiscal year 2022 competitive grant awards by the type of recipient:

With states coming from a fundamentally different direction than cities and counties, it was unusual to see this kind of agreement between the three municipal witnesses at the hearing:

- Florida DOT’s Perdue: “…the current discretionary grant process creates burdens for state DOTs and all applicants, unfairly picks winners and losers, and prioritizes non-transportation factors. Formula allocation of funds is more efficient and allows states to actually deliver infrastructure that is specific to their state and supported by their communities. FDOT encourages Congress to lay the groundwork for the next transportation authorization that revives stronger formula funding …”

- NaCo’s Winders: “…the safety and operability of county owned roads and bridges cannot continue to rely upon competitive funding opportunities. Counties urge you to provide a guaranteed funding source in the next surface transportation reauthorization.”

- The Detroit regional MPO’s O’Leary: “The array of grant programs under BIL is highly valued by SEMCOG and our peer regions to address specific local needs, particularly those that do not align with traditional formula funding parameters. However, there is a need to balance discretionary and formula funding, with a particular emphasis on increasing formula funds to ensure consistent support for foundational planning activities.” (Later, when questioned by Rep. Rick Larsen (D-WA), O’Leary clarified that more direct formula aid to MPOs would be preferable.)

(To be clear, NaCo was advocating a new formula program to give money directly to counties, while Florida DOT was advocating a return to formula money going to the states.)

Rep. John Garamendi (D-CA), for one, was having none of it. Noting the vast increase in both formula and competitive aid being provided by IIJA, he told the panel “You guys have never had it so good. Cry me a river.”

When looking at how the competitive grant programs are working, a consistent complaint was a delay in grant execution. Perdue noted “Two years after being awarded the 2021 RAISE grant for the Tampa Heights Mobility Project, FDOT’s grant agreement has still not been executed by U.S. DOT. On average, the grant funds for FDOT projects have taken up to 18 to 24 months to be authorized. Currently, FDOT has received authorization for 13.68% of our awarded grants − leaving 86.32% waiting for a grant agreement and funds to be obligated by U.S. DOT…

Perdue added, “to meet the federal match requirements for application submissions, a 20% match of state funds must be committed. While applicants wait months for paperwork to be reviewed, a considerable amount of resources in FDOT’s Work Program are essentially sidelined in anticipation of a potential grant award. Since the inception of IIJA, FDOT has had to set aside resources totaling over $430 million in the pursuit of discretionary grant funding at one time or another. While waiting for an award announcement, this money was not building infrastructure, instead it was waiting to learn if we would be selected. In Florida, we are aware that some industry partners are opting to not apply for federal discretionary grants to ensure their funding cycles can remain active and reliable.”

Winders concurred: “While federal permitting problems are a familiar source of frustration for local governments, an emerging issue among IIJA awards has become more pointed: the time it takes to execute a grant agreement. Counties and other eligible entities are reporting unprecedented timelines of up to 24 months, compounding the effects of permitting delays by further degrading federal and local investments and slowing down the delivery of critical projects. Counties strongly encourage USDOT to address this issue. The county message is simple: get grant funds out as quickly as possible to the communities where they are needed most. In the current economic environment, construction materials are extremely expensive, and delays can result in unmanageable project cost increases. Inflation, combined with the four-year expiration date on most USDOT funds, can have disastrous consequences for the IIJA’s investments.”

(Later, Rep. David Rouzer (R-NC) concurred, saying that his state DOT had been awarded an INFRA grant in October 2022 that was still not executed, and in the interim, the project had seen its price tag jump from $640 million to $839 million.)

One common theme was that the application process is difficult, especially for smaller municipalities that lack full-time grant-writing staff and lobbyists. Chairman Sam Graves (R-MO) questioned Winders about a specific project in Graves’ area of Missouri that has been rejected six separate times for a RAISE grant, and Winders said that on multiple occasions, when they redid their application to take advantage of post-denial critiques from USDOT, their application was scored worse the following year. Multiple witnesses said that more transparency and objectivity in the process would be welcome.

Another variant of the “process is biased against small towns and rural areas” argument came from Rep. Pete Stauber (R-MN), who noted that the definition of “rural” for most DOT IIJA programs is basically any spot of land that is not in an urbanized area with a population of 200,000 or more. Stauber said that in his home state, every urbanized area except for Minneapolis-St Paul is under 200K, which means that truly rural towns with 3,000 people are fighting it out with reasonably well-heeled suburban areas with populations north of 150,000 and the tax base to match. Stauber said he had legislation to reset that population threshold at 20,000.

Rep. Brian Babin (R-TX) also pointed out that some small communities that are applying for aid for the first time don’t know that transportation grant programs are unusual in that they are reimbursable – the non-federal partner has to spend their own money to build the thing, and once it’s done, the federal government reimburses them x percent of the cost (usually from 50 to 80 percent). Babin said that some small communities may not have the cash to be able to front Uncle Sam the construction money.

The lone non-governmental witness, our old friend Chuck Baker from the Short Lines, had a different perspective. Since the prospect of direct federal formula aid to for-profit railroads was, and forever shall be, a non-starter, Baker was left to criticize the relative prioritization of federal grant funding from the IIJA. In particular, the CRISI program, he said, should be more focused on projects for freight railroads, because the overall excessive prioritization of passenger rail (both Amtrak and new capacity) in all the rest of the IIJA’s rail grant funding. He also said that the funding certainty provided by the five-year advance appropriations in the IIJA was extremely helpful and that some kind of advance funding for many of these programs should be continued.