(Some of this material appeared, in earlier form, in the September 9, 2009 issue of Transportation Weekly.)

The water wars.

Presidents Carter and Reagan disagreed on many things, but they shared a deep suspicion that many Corps of Engineers water projects were wasteful and that the Corps itself was too focused on pleasing Congress. Carter blew much of his legislative momentum in his first year in office by starting a “water war” with Congress by trying to halt dozens of Corps and Bureau of Reclamation projects. He finally agreed with Congress on new user revenues for inland waterway projects in the Inland Waterways Act of 1978 (P.L. 95-502), creating a new trust fund supported by a tax on the diesel fuel used to tow barges.

However, the rest of the process was still broken. The Water Resources Development Act of 1979 (H.R. 4788, 96th Congress) passed the House but never made it out of committee in the Senate. Neither chamber bothered to attempt a bill during the first two years of the Reagan Administration due to White House opposition and the prevailing mood. The Water Resources Development Act of 1983 (H.R. 3678. 98th Congress) passed the House and was reported from committee in the Senate but never brought up on the Senate floor before the Congress ended in 1984.

The ongoing lack of new authorizations also had an effect on annual appropriations for water projects. One scholar added it up and found that “Federal outlays for water projects dropped by almost 80 percent, from $6 billion per year in 1968 to $1.3 billion in fiscal 1984, and from 1977 to 1983 more Corps civil works projects were canceled than were authorized…”[1]

In a nutshell, both Carter and Reagan wanted the non-federal beneficiaries of more types of water projects to contribute a share of the costs. A 1983 Congressional Budget Office study summed up the existing law for Corps project cost-sharing at that time:

Under current policy, nonfederal cash contributions are not required for commercial navigation projects (ports, harbors, and waterways); structural flood control projects (reservoirs, levees, flood walls, and the like); hydroelectric power projects; water supply components of multipurpose reservoirs; or joint costs of fish and wildlife enhancement, recreation, or water quality features of multipurpose projects. Up-front cash contributions are required from nonfederal sponsors to cover 25 percent of separable fish and wildlife costs (for example, fish hatcheries) and 50 percent of separable recreation costs (such as boating or swimming facilities). For Corps projects, nonfederal sponsors are required to provide necessary land easements and rights-of-way. On average, they have accounted for 14 percent of urban flood control capital costs, 5 percent of rural flood control capital costs, 14 percent of port development costs, and 5 percent of inland waterway project capital costs. Nonfederal participants must repay within 50 years the capital costs of providing water supply storage and hydroelectric power.

The Corps pays all operation and maintenance (O&M) costs for navigation projects, major flood control reservoirs, and joint costs of multipurpose reservoirs. Nonfederal sponsors pay O&M for all other types of projects – local flood control, drainage, hydropower, water supply, irrigation, and separable cost of multipurpose reservoirs.[2]

What was the point of cost sharing? “Advocates of these new cost-sharing rules promised that the allocation of federal funds to Corps projects would result in more efficient use of tax dollars because water projects would have to meet the test of the market. They reasoned that if a local project sponsor was neither capable nor willing to share the costs of a project, it was not worth building and that only truly good projects would receive local financial backing and be constructed. Advocates also argued that the legislation would spread a limited construction budget across a greater number of projects.”[3]

1984-1985: Cost-sharing proposed and rejected.

Reagan promoted his cost-sharing ideas through his budget requests. The Senate at the time was controlled by Reagan’s Republican party, and its leaders were forced to take Reagan’s budget requests much more seriously than were their Democratic House counterparts. In January 1983, Reagan’s fiscal 1984 budget request assumed legislation raising over $400 million per year in new Corps user fees in three areas: deep draft port dredging projects, recreational facilities operated by the Corps, and additional charges on inland waterways users. The budget also assumed additional cost sharing by local sponsors for flood control projects.

But by the following year, the FY 1985 budget request had been downsized so it only recommended $200 million in annual user fee receipts, and only for deep draft port dredging. The ill-fated 1983-1984 WRDA bill made some progress in this regard. The Senate bill (S. 1739, 98th Congress) required a local cost share of 50 percent of local flood control projects. And for harbor improvements, the Corps was given the responsibility for keeping the harbor dredged to a depth of 45 feet, with the local entity responsible for 50 percent of the cost of keeping it dredged below that level. The House companion bill (H.R. 3678, 98th Congress) required a non-federal cost share of 25 percent for flood control projects. The bill also established a Port Infrastructure Development and Improvement Trust Fund account in the Treasury, but since the bill did not go to the Ways and Means Committee, it had no provision to raise new revenues for the Trust Fund.

Up until this point, the Appropriations Committees had stayed within the rules and, by and large, refused to appropriate funds for Corps water projects unless authorized by law. But the eight-year lapse since the last omnibus WRDA bill (which was enacted in 1976) and the fact that 1984 was an election year was too much to bear, and as the Congress was preparing to wrap up its business by passing a continuing resolution appropriating funds to keep the government going so that legislators could go home and campaign for re-election, problems arose. The House Rules Committee issued a rule (H. Res. 586, 98th Congress) that would have prevented any amendments adding water projects from being added to the “CR” (because of its must-pass-or-the-government-shuts-down nature and because of a loophole in House rules allowing some nongermane amendments to be offered to CRs under regular order, a CR is a very popular “Christmas tree” on which to hang amendments).

But the House, starved for new water projects six weeks before the elections, voted down the rule by a vote of 168 to 225 on September 20. Because of the intervening weekend, it took five more days before Rules was able to report (and the House pass) a revised rule allowing amendments, under which Rep. Bob Roe (D-NJ) from the Public Works Committee offered an amendment containing the text of the House WRDA bill to the CR, which passed (336 to 64). But this delay meant the Senate had to wait an additional week until it could start debating the CR, which kept Congress in session longer and led to legislators in both chambers missing a week of campaigning.

The House-Senate conference committee on the CR dropped the WRDA legislation from the final version of the bill after the White House indicated they would not accept the new project authorizations without additional cost-sharing language.[4]

1985-1986: Enactment of the HMT and HMTF for cost-sharing.

When the 99th Congress convened the following year, there was additional impetus to work through the logjam. Both the House and Senate committees of jurisdiction started working on omnibus WRDA bills again. But before the committees could report those bills, it was time for the annual spring supplemental appropriations bill to make its way through the House. The bill (H.R. 2577, 99th Congress) came to the floor containing a $150 million appropriation for water projects, half of which were not authorized by law. The appropriators asked the Rules Committee to protect the provision from a point of order against unauthorized appropriations, but the Public Works Committee’s leadership told Rules they would object to the waiver unless the supplemental bill carried the entire draft House WRDA bill, which the appropriators refused to do.

So the rule (H. Res. 186, 99th Congress) did not protect the $150 million in projects – the point of order was indeed made and that whole appropriations paragraph was stripped from the bill. Appropriations chairman Jamie Whitten (D-MS) then offered an amendment reinstating the entire $150 million for all of the projects (not just the money for the authorized projects, as some had expected him to do). Robert Edgar (D-PA) then offered an amendment to Whitten’s amendment lowering the dollar amount by $99 million to prevent funding of the unauthorized projects. This amendment passed by one vote (203 to 202), killing the projects.[5]

When the bill got to the Senate, Republican leaders were determined to find middle ground in order to fund some of the water projects. Though the supplemental appropriations bill was reported out of committee under a veto threat, once it got to the floor, an agreement was reached between the White House and Senate Republicans on cost-sharing conditions that would allow project funding to move forward (subject to the cost controls later being written into law in the forthcoming WRDA authorization) and the deal was outlined in a Senate floor colloquy in the Congressional Record (see here starting on page 16708).

In that colloquy, Majority Leader Bob Dole (R-KS) said that the agreement included “a 0.04 percent ad valorem tax on imports and exports to recover 30 to 40 percent of Corps of Engineers harbor operations and maintenance expenditures. Money raised by this tax will be deposited in a dedicated O&M Trust Fund.” However, the House was not a part of these negotiations and did not feel bound by the deal in its entirety.

The House Public Works and Transportation Committee reported its WRDA bill (H.R. 6, 99th Congress) on August 1. The House bill included cost sharing for port construction, on a sliding scale with the non-federal share being ten percent for the shallowest ports up to fifty percent for the deepest ports, similar to the levels agreed to by Reagan and the GOP Senators.

The Public Works bill also included a title imposing a new 0.04 percent tax on the value of cargo loaded or unloaded at U.S. ports and creating a new Port Infrastructure Development and Improvement Trust Fund into which the new taxes were to be deposited. However, neither the tax increase nor the Trust Fund creation was actually within the jurisdiction of the Public Works Committee, so H.R. 6 was immediately referred to the Ways and Means Committee, which held a hearing on September 6.

At the hearing, Bob Dawson (then the Deputy Assistant Secretary of the Army for Civil Works), speaking on behalf of the Corps and the Treasury Department, endorsed the proposed 0.04 percent tax, saying:

…our Departments very strongly support the necessity for new revenue measures to generate funds for maintaining and improving our Nation’s harbors and waterways. We do not believe that there is any justification for continuing the degree of subsidy which now exists for these commercial projects. I might point out, many of the parties affected by this legislation have joined with us in recognizing this reality. We believe that while revenues to be obtained from the new fees are small, from a Federal deficit point of view, they do represent a substantial contribution from the users of these projects to the costs of providing these services. Moreover, it is the administration’s intent not to initiate any new port or inland navigation construction projects until legislation providing for enhanced navigation cost recovery is enacted.[6]

On September 18, the House Ways and Means Committee approved its (revised) portion of the bill, levying the new 0.04 percent tax on the value of cargo imported and exported through ports in order to help raise money to pay for the federal share, as per the Senate agreement, and creating the new port trust fund. The Ways and Means Committee reported the bill on September 23, 1985 (H. Rept. 99-251, Part 3) .

But the House bill did not increase the federal cost share of inland waterways projects or increase the excise tax on barge diesel fuel for the Inland Waterways Trust Fund, as Reagan and the Senate wanted. The House committee report (H. Rept. 99-251, Part 1) said that “a high level of cost recovery would have serious adverse economic impacts, not only on the inland waterways transportation industry, but on many major commodities such as agriculture, coal, steel and steel products, and sand and gravel.”[7]

The bill eventually made it to the floor and passed the House on November 13 by the wide margin of 358 to 60.

The Senate version of the bill (S. 1567, 99th Congress) was proceeding along similar lines, but more slowly. The Public Works Committee reported its part of the bill on August 1 (S. Rept. 99-126) and the Finance Committee reported the revenue provisions on January 8, 1986 (S. Rept. 99-228). The Senate bill included all of the agreed-on cost-sharing provisions, the 0.04 percent tax on cargo value at ports, and the GOP’s doubling of the barge diesel tax for inland waterways after a long phase-in (coupled with an increase in the non-federal cost share of inland waterways projects to 50 percent). The Senate bill also changed the name of the port trust fund account to the Harbor Maintenance Trust Fund.

There was one key distinction between the House and Senate trust fund provisions (aside from the name) – the Senate bill mimicked the Inland Waterways Trust Fund by capping the amount that could be appropriated from the Trust Fund at 40 percent of the operation and maintenance costs of existing port projects. Under the House bill, the Trust Fund could be used to pay up to 100 percent of O&M.

The Senate amended its bill, incorporated it into H.R. 6, and passed its amended version of H.R. 6 by March 26, 1986 and went to conference with the House. But conference dragged on, it became clear that Reagan had all the leverage and that getting a bill with popular water projects enacted before the elections depended on the House caving in to Reagan’s cost-sharing demands. It was not until the waning pre-election days of the 99th Congress that agreement was reached (after a false start on October 9, a conference report (H. Rept. 99-1013) was not filed until October 17, just three weeks before the November 8 elections).

The landmark 1986 WRDA bill became Public Law 99-662 on November 17, 1986. It kept the 0.04 percent tax on cargo value at ports, the Harbor Maintenance Trust Fund, the doubling of the Inland Waterways Trust Fund diesel tax, and most of the cost-sharing measures from the Senate bill, including the rule that the HMTF would pay for 40 percent of the federal share of harbor dredging. At the time, it was estimated that the cargo tax at ports would raise almost $200 million in 1998 and almost a billion dollars over a five-year period.[8]

The rate would not stay at 0.04 percent for long.

1990: A tax increase for deficit reduction (and a higher HMTF cost share).

In January 1990, George H.W. Bush’s first full budget (for FY 1991) proposed to increase the Harbor Maintenance Tax “from 0.04 percent of cargo value to approximately 0.125 percent of cargo value. This increase would fully offset the cost of Corps of Engineers harbor maintenance dredging; currently 40 percent of the cost of the program is recovered by the fee. It would also offset the cost of certain National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration marine programs, including coastal mapping, marine weather, and circulation and tide data.” Their budget predicted that the increased fee would raise about $300 million per year on a net basis, after the income tax offset.

(Any excise or payroll tax takes money out of the economy that would otherwise be income for someone, somewhere. So every dollar of excise or payroll tax reduces income tax collections by some unknown amount – less taxable income equals less income tax paid. The old convention was to assume that for every dollar of excise or payroll tax, income tax receipts would be reduced by 25 cents. When depositing excise or payroll taxes in a trust fund account, the trust fund is credited with the gross amount, while the offset deduction is taken from the general fund.)

At the House Appropriations hearing in February 1990 on the Corps budget request, subcommittee chairman Tom Bevill (D-AL) submitted questions for the record asking if the Corps had discussed the proposed harbor tax increase with shippers (answer: no) and if they thought that project users would support the tax increase (answer: evasive).

The next month, the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee sent the Senate Budget Committee its views on the 1991 budget request, which said (on page 8 of the letter), “We believe that, if a proper definition of maintenance covered under the ad valorem fee increase proposal can be developed, the authority to utilize funds for 100% of such costs from the Harbor Maintenance Trust Fund will be included in the 1990 Water Resources Development Act. We would note, however, that the Finance Committee has jurisdiction over the raising of the level of the harbor fee itself.”

All discussion of taxes and spending that year quickly became wrapped up in bipartisan “budget summit” talks between the Bush White House and Congress, which began in early May, got serious after Bush signaled his willingness to break his “read my lips – no new taxes” pledge in late June, and culminated in a bipartisan agreement on September 30, 1990. The summit agreement promised $500 billion in deficit reduction over the five-year 1991-1995 fiscal period (using OMB numbers).

Of that $500 billion, $134 billion was to come from increased tax receipts (about $10 billion from better IRS enforcement and the other $124 billion from rate increases). There were no income tax rate increases in the original deal, but it was heavy on excise tax increases, particularly in transportation, which had $69 billion of the five-year tax increases. Most of that was a proposed 10 cent per gallon hike in gasoline and diesel taxes and increases in aviation excise taxes, but the original summit agreement also adopted the proposal from Bush’s budget request eight months prior to increase the Harbor Maintenance Tax to 0.125 percent, reducing federal deficits by $1.8 billion over five years.

The House voted down the original version of the agreement on October 4 by a bipartisan vote of 179 yeas, 254 nays – liberal Democrats did not like the entitlement cuts or the regressive nature of the excise and payroll tax increases, and conservative Republicans did not like any tax increases at all. Many transportation advocates also voted no because they did not like the idea of increasing transportation excise taxes for deficit reduction. Democrats then regrouped and wrote their own budget deal (with President Bush’s support) which had less entitlement cuts and more taxes (income tax rate increases on top earners replaced some of the excise and payroll taxes). The Harbor Maintenance Tax increase stayed intact throughout the process and was enacted into law in the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990 (Public Law 101-508), which implemented the budget agreement.

The harbor provision mostly flew under the radar and wasn’t mentioned in debate, but there was one difference between the House and Senate versions of the reconciliation bill (H.R. 5835, 101st Congress) – the Senate bill included the increase in the HMTF cost share of dredging projects from 40 percent to 100 percent of the federal share, while the House bill did not. The final law did not increase the HMTF share, but 23 days after the reconciliation bill was signed into law, the Water Resources Development Act of 1990 was signed into law (Public Law 101-640), and section 316 of that law increased the HMTF share to 100 percent.

At the time Congress was considering the bill, the Joint Committee on Taxation estimated that the HMT increase would raise an additional $314 million in 1991, $342 million in 1992, $369 million in 1993, $395 million in 1994 and $422 million in 1995, or $1.842 billion over five years. That $1.842 billion was counted towards the $137.169 billion in increased tax revenues under the bill, which was, in turn, counted towards the $496.3 billion in deficit reduction over five years as part of the overall agreement. (The difference between $496 billion and $500 billion was the difference between CBO estimates and OMB estimates.)

| The Enacted 1990 Budget Agreement (CBO/JCT Score) (Billion $) |

| 5-Year Total Deficit Reduction, FY 1991-1995 |

496.3 |

100.0% |

|

Spending Cuts |

|

|

|

|

New Discretionary Spending Caps |

182.4 |

36.8% |

|

|

Mandatory Spending Reductions |

98.9 |

19.9% |

|

Revenue Increases |

137.2 |

27.6% |

|

Increased IRS Compliance |

9.4 |

1.9% |

|

Net Interest Savings From Above |

68.4 |

13.8% |

And the tax increases did not occur in a vacuum – the 1990 law also created new caps on total discretionary appropriations for each fiscal year of the deal (three caps – defense, non-defense, and international affairs). This was intended to keep total appropriations from growing too quickly, totaling $182 billion in savings versus the inflation-adjusted baseline over five years. The effect of this was that, even though the HMTF cost share of O&M dredging projects went from 40 percent to 100 percent, HMT spending was not able to increase as quickly as the tax receipts increased.

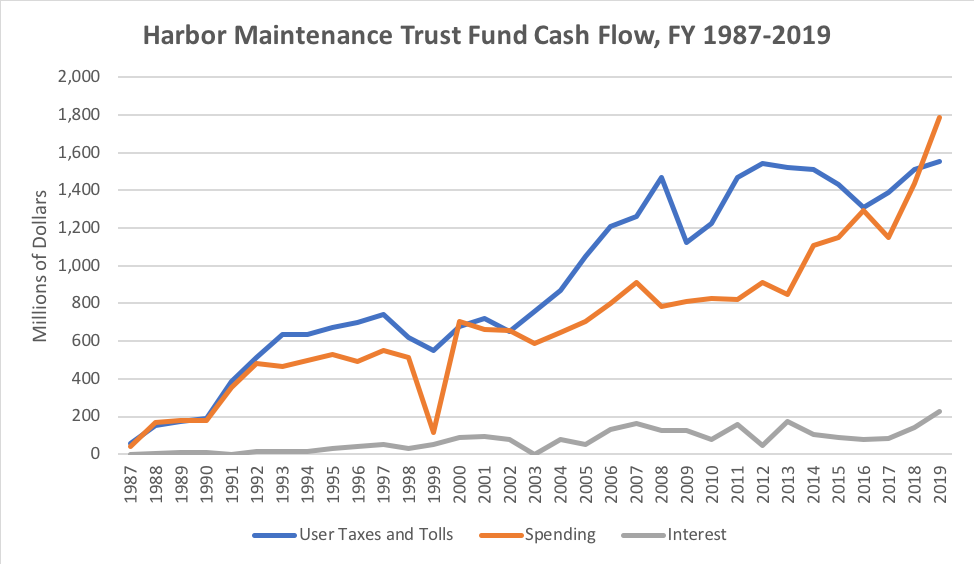

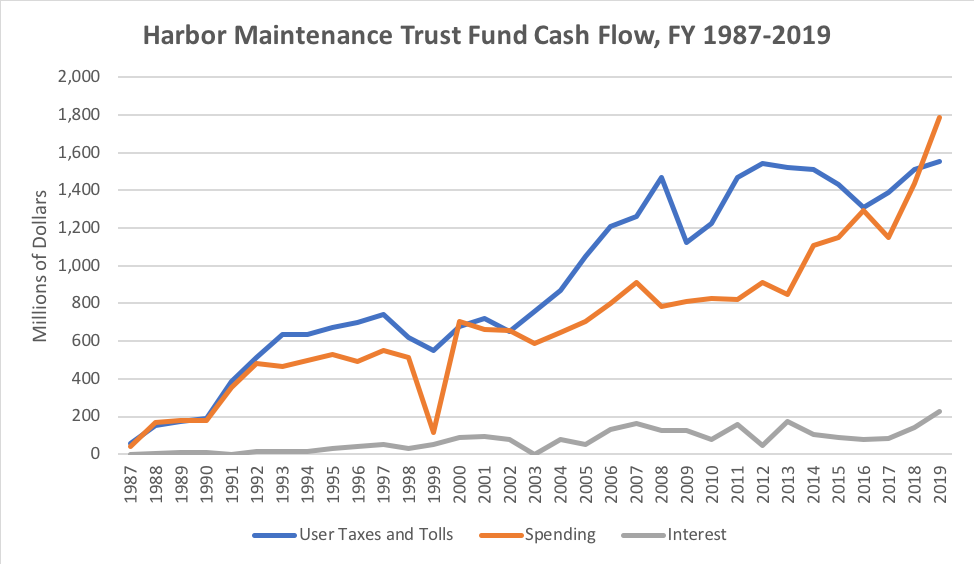

In FY 1990, the year before the increase, the HMT tax receipts were, coincidentally, the same amount as appropriations out of the Trust Fund – $180 million. But over the next five years, tax receipts totaled almost $500 million greater than spending, leading to the first significant balance buildup (at the end of FY 1990, the cash balance in the Trust Fund was only $30 million, but at the end of FY 1995, between the tax to spending imbalance and compound interest, the balance was $621 million.

| (Million $) |

FY 1990 |

FY 1991 |

FY 1992 |

FY 1993 |

FY 1994 |

FY 1995 |

5-Year |

| HMT Receipts |

180 |

374 |

506 |

628 |

622 |

671 |

2,802 |

| HMTF Spending |

180 |

353 |

483 |

466 |

497 |

531 |

2,329 |

Unlike some of the other excise taxes levied by the 1990 budget agreement, the HMT increase was not temporary and did not expire at the end of the five-year deal. And the spending caps were extended as well, which (when combined with a budget-cutting Republican Congress that took office starting in FY 1996), caused HMT receipts to exceed new appropriations by an additional $500 million over the next three years, from FY 1996 to 1998, which (again combined with compound interest) pushed the end-of-1998 balance north of $1.2 billion.

Then the Supreme Court got involved.

1998: The Supreme Court says the HMT is not a user fee.

The ad valorem (on value) method of taxation was originally selected primarily because it is easy and cheap to administer – bills of lading containing the dollar value of cargo are already submitted as part of the import/export process. But taxing based on the dollar value of the product diminishes the relationship between the level of taxation and the value of the benefit provided by the government in exchange for the tax payment.

Picture two identical freighters. One is full of a heavy bulk cargo, like, for example, some kind of mineral ore. The other is full of containers of iPads from China (each iPad safely encased in its own lightweight protective packaging to avoid breakage, of course). The freighter full of mineral ore will be much heavier, and as a result, will sit lower in the water and require more clearance from the floor of the port. These are the costs that the HMT is supposed to recoup – the costs of dredging deep draft ports for the vessels with the deepest draft. But the way the Harbor Maintenance Tax is constructed, the freighter full of iPads would pay far more in taxes than would the freighter full of mineral ore because the total dollar value of a shipload of electronics is much greater than that of a shipload of mineral ore – even though the freighter with the iPads has a more shallow draft and therefore is using less of the Corps’ services. From this perspective (the “benefit taxation” model), the HMT as currently structured makes little sense and bears almost no resemblance to a true “user fee.”

And the distinction between a tax and a user fee is not just academic. The Constitution flatly forbids any tax or duty on exports going from the U.S. to a foreign country, but the courts have ruled that the prohibition “does not rule out a ‘user fee,’ provided that the fee lacks the attributes of a generally applicable tax or duty and is, instead, a charge designed as compensation for Government-supplied services, facilities, or benefits.”[9] In March 1998, the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously held that the HMT was indeed a tax, not a user fee, and struck down its application to exports.

In the opinion (U.S. v. United States Shoe Corp., 523 U.S. 360), written by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the Court determined that the HMT “is determined entirely on an ad valorem basis. The value of export cargo, however, does not correlate reliably with the federal harbor services used or usable by the exporter…the extent and manner of port use depends on factors such as the size and tonnage of a vessel, the length of time it spends in port, and the services it requires, for example, harbor dredging…we must hold that the HMT violates the Export Clause as applied to exports. This does not mean that exporters are exempt from any and all user fees designed to defray the cost of harbor development and maintenance. It does mean, however, that such a fee must fairly match the exporters’ use of port services and facilities.”[10]

The government immediately stopped collecting the HMT on exports. In the immediate aftermath of the decision, amidst uncertainty over how much HMTF receipts would drop because of the ban on export collections, Congress essentially gave the Trust Fund a one-year holiday. In the 1999 Energy and Water Development Appropriations Act (Public Law 105-425), in the appropriations paragraph for the Corps’ Operation and Maintenance account, Congress (for the first and only time since the inception of the HMTF) did not include the traditional language saying that “such sums [of the appropriation] as become available in the Harbor Maintenance Trust Fund, pursuant to Public Law 99-662, may be derived from that Fund.”

Congress did appropriate FY 1999 funds from the HMTF for Corps General Construction and for the St. Lawrence Seaway, but total spending drawn from the Trust Fund dropped from $511 million in FY 1998 down to $117 million in 1999, before rising back up to $702 million in 2000. The $400-ish million from that one-year holiday, plus 20 years of accumulated interest, is still in the Trust Fund today.

Congress later amended the statute in 2005 to clarify that it did not apply to exports.

1999: Clinton proposes a real harbor user fee.

The following year, the Clinton Administration in its FY 2000 budget proposed to replace the HMTF and the tax with a new Harbor Services Fund supported by real, bona fide user fees that could be levied on both imports and exports, consistent with the U.S. Shoe opinion.

The Analytical Perspectives volume of that budget (p. 100) called it a “cost-based user fee” and said “Through appropriations acts, the fee will raise an average of $980 million annually through FY 2004, which is less than would have been raised by the Harbor Maintenance Tax before the Supreme Court decision that the ad valorem tax on exports was unconstitutional. While the collections from the harbor services fee would be mandatory, collections would be available to offset discretionary spending.”

The implementing bill was transmitted to Congress in May 1999 and introduced in the House as H.R. 1947 (106th Congress). It set fees of 12 cents per net ton for bulk carriers, 28 cents per net ton for tankers, 12 cents per gross ton for cruise ships, and $2.74 per gross ton for general ships. The bill cleverly prevented balance buildups in the fund: “If amounts appropriated in any fiscal year are less than the amount collected in fees for the prior fiscal year, then the rate of the fee for each vessel category shall be reduced in the year of the appropriation so as to result in collections not exceeding the total amount appropriated from the Harbor Services Fund for that fiscal year.”

The Clinton Administration reiterated the proposal in its final budget, for FY 2001, but Congress never took any action on the proposal. (The Administration did defend the proposal and its methodology in responding to some questions for the record at a Senate hearing – see here on pp. 54-56.) Part of that inaction was timing – Congress was fast out of the gate on the WRDA bill in 1999, and the bill had already been reported out of committee in both chambers before the Administration submitted its bill. The inaction may have been due, in part, to a Congressional Budget Office determination that the proposed fee, as constructed by the Administration, was one of several “fees that the Administration employs to offset discretionary spending but that CBO believes cannot be used for that purpose under the provisions of the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act of 1985, as amended.”[11]

2001: China gets permanent MFN trade status.

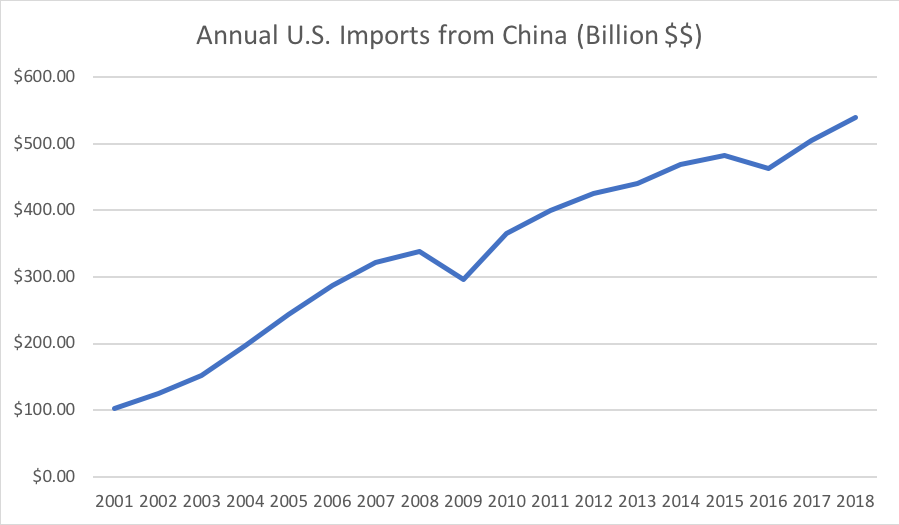

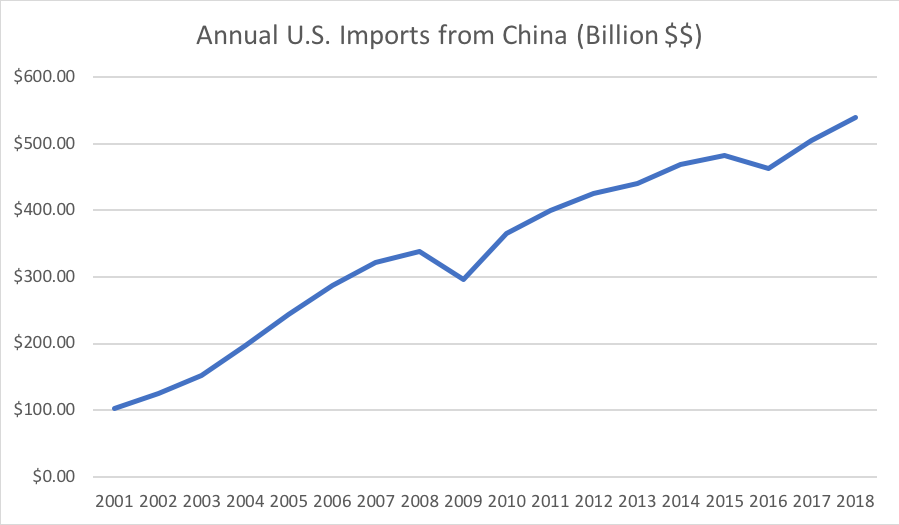

In October 2000, President Clinton signed Public Law 106-286, which allowed China’s provisional “most favored nation” trade status to become permanent, effective upon China’s accession as a member of the World Trade Organization. This happened in December 2001, and starting in 2002, U.S. imports from China started to skyrocket, from just over $100 billion in 2001 to $321 billion in 2007. Then, after a brief recession dip, imports from China hit $400 billion in 2011 and $500 billion in 2017.

Much of these imports came by ship, so even though the HMT rate has not increased since 1990, receipts from the tax doubled between 2001 and 2008 (from $722 million in FY 2001 to $1.467 billion in 2008).

But even though the statutory caps on discretionary appropriations expired in 2003 (they were re-imposed in 2011), Congress did not increase appropriations from the HMTF to match the explosive growth of tax receipts. Appropriations out of the Trust Fund were $660 million in FY 2001 and by 2008 had only risen to $786 million. The 2008 HMTF spending level was only 19 percent higher than in 2001 while the HMTF tax receipt level had doubled. With the power of compound interest, the year-end unexpended balance in the Trust Fund had gone from $1.8 billion at the end of 2001 to $4.6 billion at the end of 2008.

The off-budget movement.

Starting in the mid-1980s, members of what was then called the House Public Works and Transportation Committee started agitating to have some or all of the transportation-related federal trust funds taken “off-budget” so they could spend all of the income, and accumulated balances, of those trust funds. This started before the HMTF existed, but in the 1990 reconciliation bill that increased transportation excise taxes, Public Works had been ordered to report provisions that created $254 million in savings over five years. Instead, Public Works reported provisions that would have spent all of the gas tax increase, reauthorized the FAA, and taken the Highway Trust Fund, Airport and Airway Trust Fund, Inland Waterways Trust Fund, and Harbor Maintenance Trust Fund off-budget.

(Ed. Note: In those days, the Public Works Committee viewed the budget reconciliation process as a way to say a very public “up yours” to the Budget Committee.)

The Budget Committee struck out almost all of the Public Works provisions as the bill went to the House floor, of course, but the Public Works members did not stop trying. However, they didn’t always try for all four trust funds at once. Public Works chairman Glenn Anderson (D-CA) introduced a stand-alone bill in January 1991 (H.R. 243, 102nd Congress) taking the HMTF off-budget, which went nowhere.

In 1996, the movement had a high-water mark – on April 17, the House passed, by a vote of 284 to 143, a bill (H.R. 842, 104th Congress) taking all four transportation trust funds off-budget. Some who voted for the bill were secure in the knowledge that the Senate Budget Committee was never, ever, in 1000 years going to let that bill come before the Senate, but even so, it was an impressive accomplishment.

In the following Congress, highway advocates succeeded in getting special budgetary treatment for the Highway Trust Fund to “unlock” its receipts and balances as part of the 1998 TEA21 surface transportation law. Because the Highway Trust Fund was and is so much larger than the others – at the time the 1996 bill was being debated, the HTF’s annual tax receipts were over 3.5 times as much as those of the other three trust funds combined, and spending down its $19 billion accumulated balance was a much bigger priority than spending down the Harbor Maintenance Trust Fund balance which, at the time, was a piddling (by comparison) $621 million.

The success of the effort to take the Highway Trust Fund off-budget (or as close as that was possible to get) took a lot of steam out of the efforts to do the same for the other trust funds. A similar effort for the Airport and Airway Trust Fund had limited success as part of the 2000 AIR-21 aviation reauthorization law. After Bud Shuster (R-PA) retired from Congress in early 2001, the issue largely lay dormant until 2009 (after HMTF balances had boomed), when legislators began introducing bills to require HMTF balance spend-down.

One such bill (H.R. 4844, 111th Congress) garnered 73 bipartisan cosponsors, and a Senate companion bill (S. 3213, 111th Congress) actually got a hearing in November 2010.

But as the 1996 experience had shown, stand-alone off-budget bills stood no chance in the Senate. Instead, harbor advocates tried to use the biennial Water Resources Development Act process to liberate HMTF funding. Section 2007 of the WRDA bill reported from the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee in September 2010 (H.R. 5892, 111th Congress) would have required all new HMTF receipts and interest to be spent every year, but that version of the bill never made it to the House floor.

By 2011, the House version of the stand-alone bill requiring all new HMTF taxes and interest to be spent every year (H.R. 104, 112th Congress) got 196 cosponsors – almost half the House – and the Senate counterpart (S. 412, 112th Congress) got 37 cosponsors. However, that Congress never considered a WRDA bill, so the issue was held over until the next Congress.

The 113th Congress did develop bipartisan WRDA legislation, and after lengthy negotiations with the Budget and Appropriations Committees, section 2101 of the final law (Public Law 113-121) set a series of escalating levels for appropriations out of the HMTF – from 67 percent of total HMTF receipts and interest in fiscal year 2015, rising slowly to 100 percent of total HMTF receipts and interest in FY 2025. Section 2102 of the law then established a variety of directed uses for HMTF funds for any amounts appropriated that exceeded the FY 2012 appropriation.

The Appropriations Committees have met and begun exceeding the target appropriation levels set in the 2014 WRDA law, but those were slow targets at first, and the WRDA law did not allow spend-down of accumulated balances. The 2016 WRDA bill reported from the T&I Committee (H.R. 5303, 114th Congress) tried something clever – section 108 of that bill allowed complete HMTF balance spend-down, outside the appropriations process – but not until fiscal year 2027, which was the year after the 10-year budget scorekeeping window in use in 2016 expired.

The House Rules Committee, at the request of the Budget and Appropriations Committees, issued a “self-executing rule” that struck section 108 from the bill before it could go to the House floor, much to the chagrin of T&I ranking minority member Peter DeFazio (D-OR), who sent an angry letter to Rules and then turned against the underlying bill.

Two years later, T&I tried again – the 2018 WRDA bill (H.R. 8, 115th Congress) contained, in section 102, the same “spend it all in the 11th year” provision as the 2016 bill had. Unsurprisingly, the Rules Committee once again announced that it would bring to the floor a modified version of H.R. 8 from which the HMTF spend-down provision had been stricken. DeFazio and his chairman, Bill Shuster (R-PA), tried to offer an amendment to H.R. 8 to restore the provision, but Rules did not allow it.

Upon becoming chairman of T&I in January 2019, DeFazio tried a different tack, going back to a free-standing HMTF balance spend-down bill by exempting HMTF appropriations from the annual spending caps, which passed the House last week. Meanwhile, the revised spending caps in the 2018 and 2019 bipartisan budget deals have allowed the Appropriations Committees to finally increase the total HMTF appropriations in fiscal year 2019 to ever-so-slightly exceed the level of new receipts and interest (while still leaving a balance of over $9 billion).

Conclusion.

Over the life of the Harbor Maintenance Trust Fund (fiscal years 1987 through 2019):

- Total tax and toll receipts: $30.276 billion.

- Interest on accumulated balances: $2.360 billion.

- Spending: $23.165 billion.

[1] Committee to Assess the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Water Resources Project Planning Procedures, National Research Council. New Directions in Water Resources Planning for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Washington: National Academies Press 1999 p. 18.

[2] Congressional Budget Office. Efficient Investments in Water Resources: Issues and Options. August 1983 p. 30.

[3] New Directions in Water Resources p. 19

[4] Joseph A. Davis. “The East Lost, West Benefited: Big Water Project Bills Died But Smaller Ones Cleared.” Congressional Quarterly Weekly Report, October 27, 1984. (Retrieved online via www.cq.com).

[5] Stephen Gettinger. “Supplemental Appropriations Action: House Narrowly Votes to Cut Funding for 31 Water Projects.” Congressional Quarterly Weekly Report, June 8, 1985. (Retrieved online via www.cq.com).

[6] U.S. House of Representatives. Committee on Ways and Means. Water Resources, Conservation, Development, and Infrastructure Improvement Act of 1985. (Hearing on H.R. 6, 99th Congress, 1st Session), p. 31.

[7] House Report 99-251, Part 1, p. 7.

[8] 132 Cong. Record p. 33084, October 17, 1986.

[9] U.S. v. U.S. Shoe Corp., 523 U.S. 360, 363.

[10] U.S. Shoe, 523 U.S. 360, 369-370.

[11] Congressional Budget Office. “An Analysis of the President’s Budget Proposals for Fiscal Year 2001.” April 2000, p. 8.