Updated August 15, 2023

The following is a document explaining the federal Highway Trust Fund, based in format on the old Federal Highway Administration’s Highway Trust Fund Primer that has not been updated since 1998. This document is in a question-and-answer format – click on a question below in the table of contents and be taken to that answer, or just keep scrolling down. For more information, see Eno’s Highway Trust Fund Reference Page at enotrans.org/htf

TABLE OF CONTENTS:

What is the HTF?

What constitutes HTF tax income?

Why is diesel taxed at a higher rate than gasoline?

What other deposits are placed into the HTF?

What taxes received by the HTF are then refunded elsewhere?

What taxes received by the HTF are then transferred elsewhere?

How reliant is the HTF on fuel taxes?

What is the 80-20 highway-transit split?

How does the Treasury Department collect and account for HTF revenues?

How are HTF tax payments attributed to states?

What expenses are drawn on the HTF?

How are funds transferred between HTF accounts?

What is the HTF balance?

Why are positive cash balances necessary?

What happens when the HTF runs out of money?

What are the Byrd and Rostenkowski amendments (tests)?

What other kinds of HTF spending control are available?

Why don’t the Budget Control Act’s spending caps or sequestration affect HTF spending?

Wasn’t the HTF supposed to be at least 90 percent self-sufficient?

Appendix A – Fiscal year 2022 Highway Trust Fund operations (cash flow)

Appendix B – List of all special transfers to the Highway Trust Fund, 2008-2022

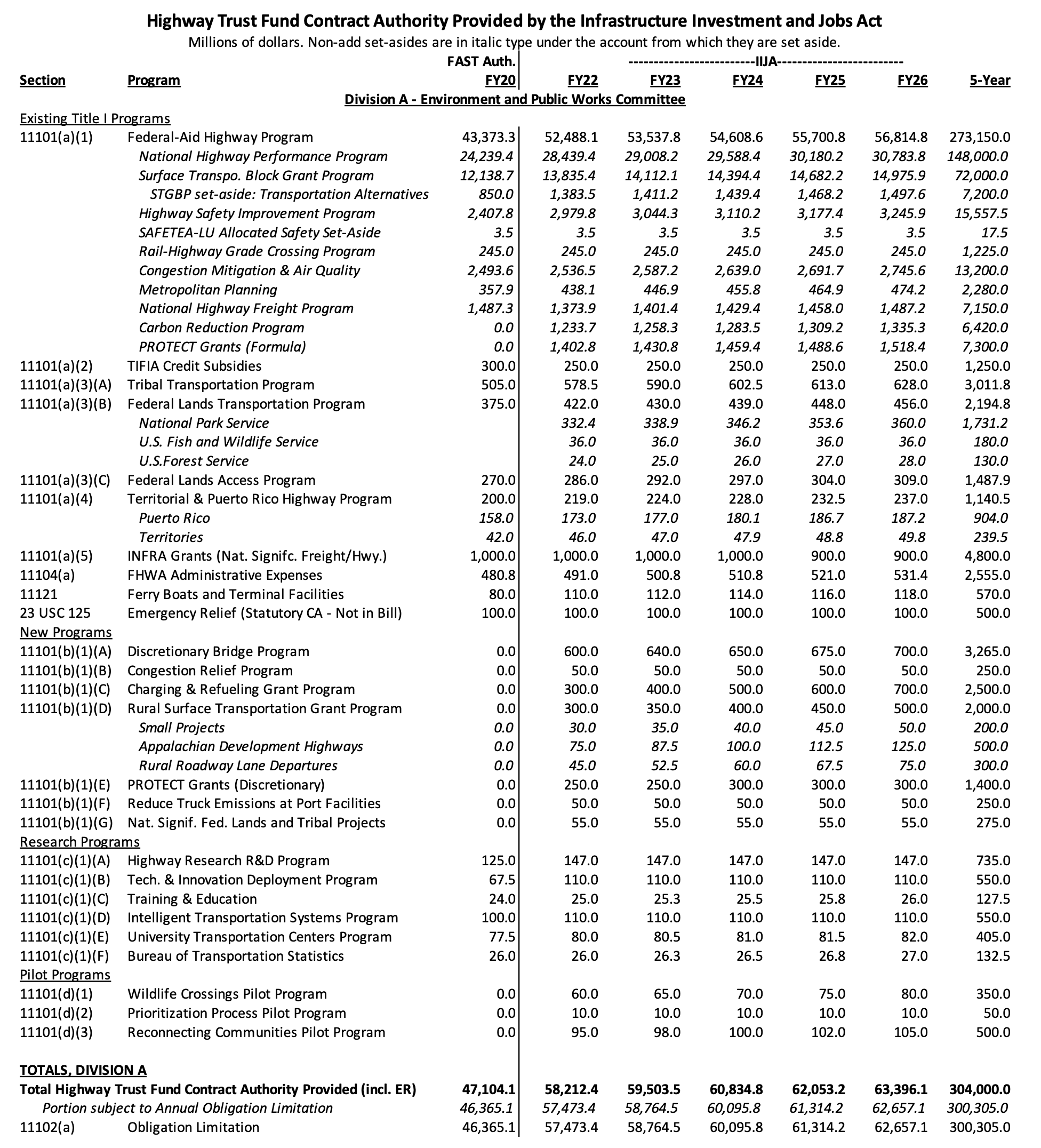

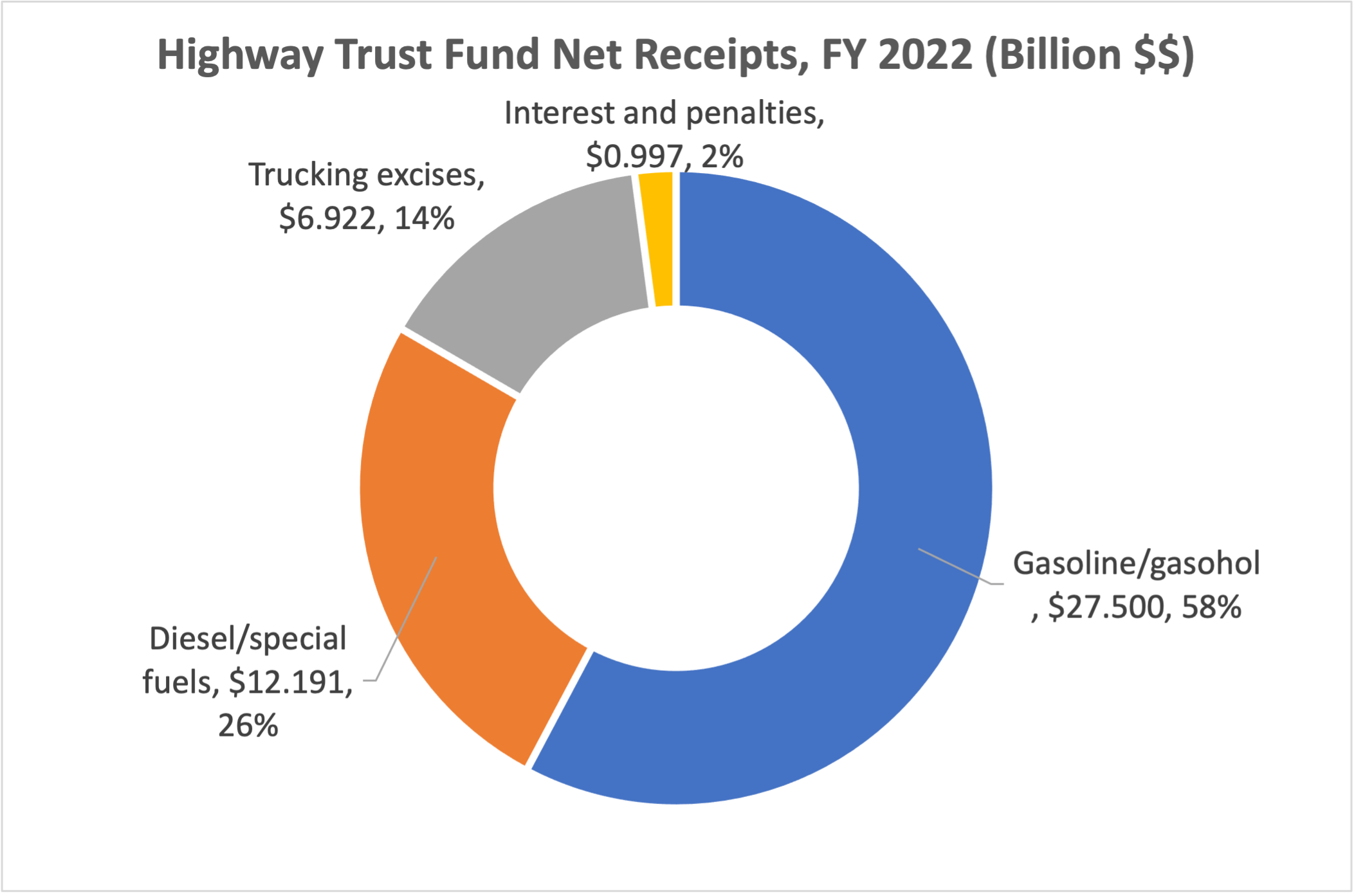

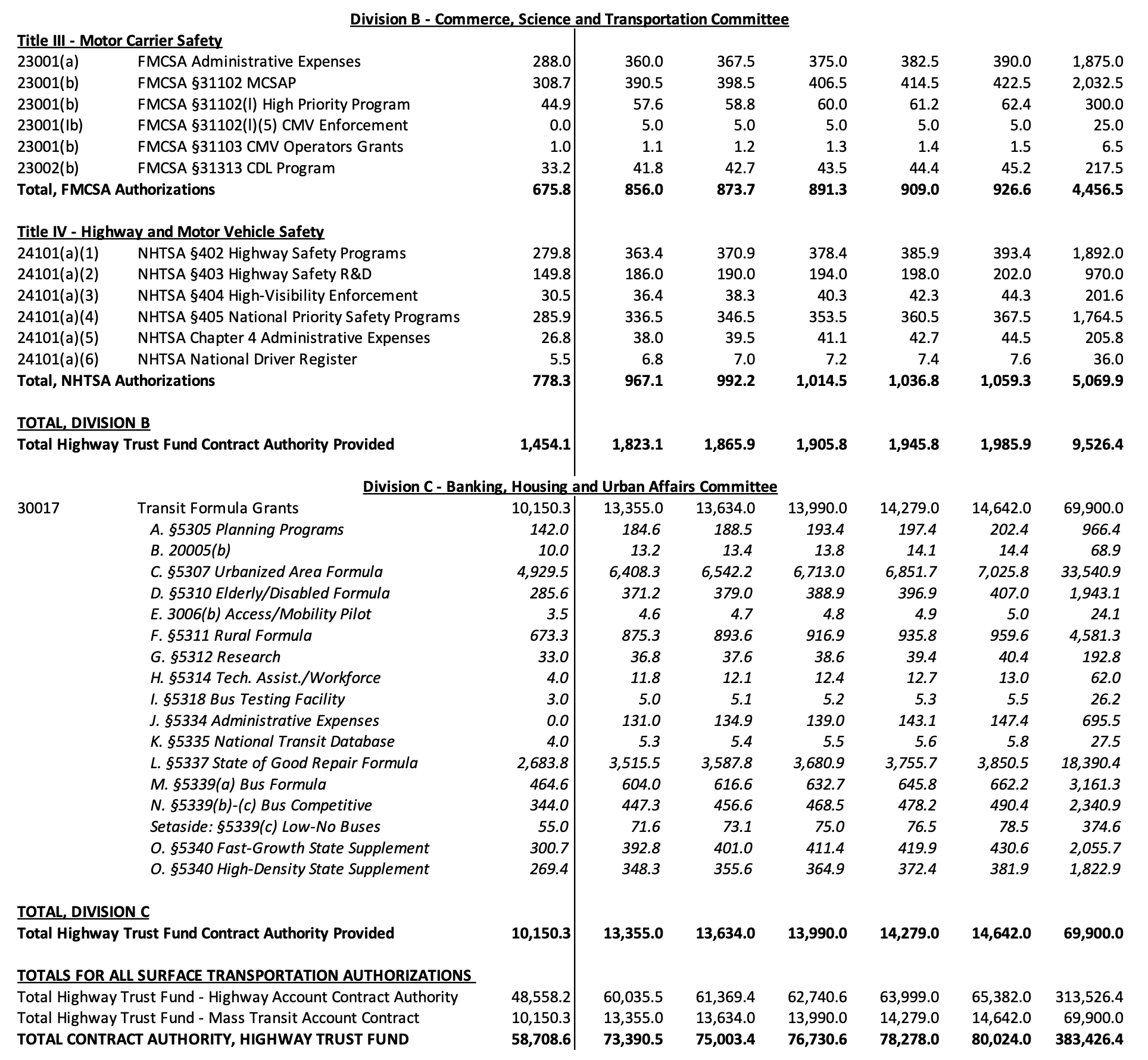

Appendix C – Authorizations for Highway Trust Fund spending in the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act of 2021

What is the HTF?

The Highway Trust Fund is a special trust fund account in the U.S. Treasury established by section 209 of the Highway Revenue Act of 1956. The Trust Fund is currently codified in section 9503 of the Internal Revenue Code. In the President’s Budget, it has the account code 069–8102–0–7–401.

From its inception on July 1, 1956 through September 30, 2022, the Trust Fund has received $1.316 trillion in net tax receipts from federal excise taxes on highway users and has paid $1.489 trillion in outlays for federal highway, mass transit, highway safety, and motor carrier safety programs. The gap between the two numbers has been filled by periodic transfers of general revenues by Act of Congress (since 2008), interest paid by the Treasury Department to itself on accumulated balances, and a small amount of fines and penalties for highway and truck safety and highway tax evasion offenses.

A federal trust fund account is not like a “real world” trust fund – the GAO Glossary notes that “a trust fund account imposes no fiduciary responsibility on the federal government.” For more information on federal trust funds generally, see this GAO report from 2001.

Since 1983, the Highway Trust Fund has had two sub-accounts: a Mass Transit Account, and everything not in the Mass Transit Account (the latter is colloquially referred to as the “Highway Account”).

The systemic imbalance between Trust Fund receipts and spending that has existed since the mid-2000s is projected by the Congressional Budget Office to cause the Trust Fund to run out of cash (again) sometime in 2028 unless Congress increases taxes significantly, cuts spending drastically, or provides yet another transfer from general revenues.

What constitutes HTF tax income?

Section 9503(b)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code provides that the receipts of five federal excise taxes are (eventually) deposited in the Highway Trust Fund:

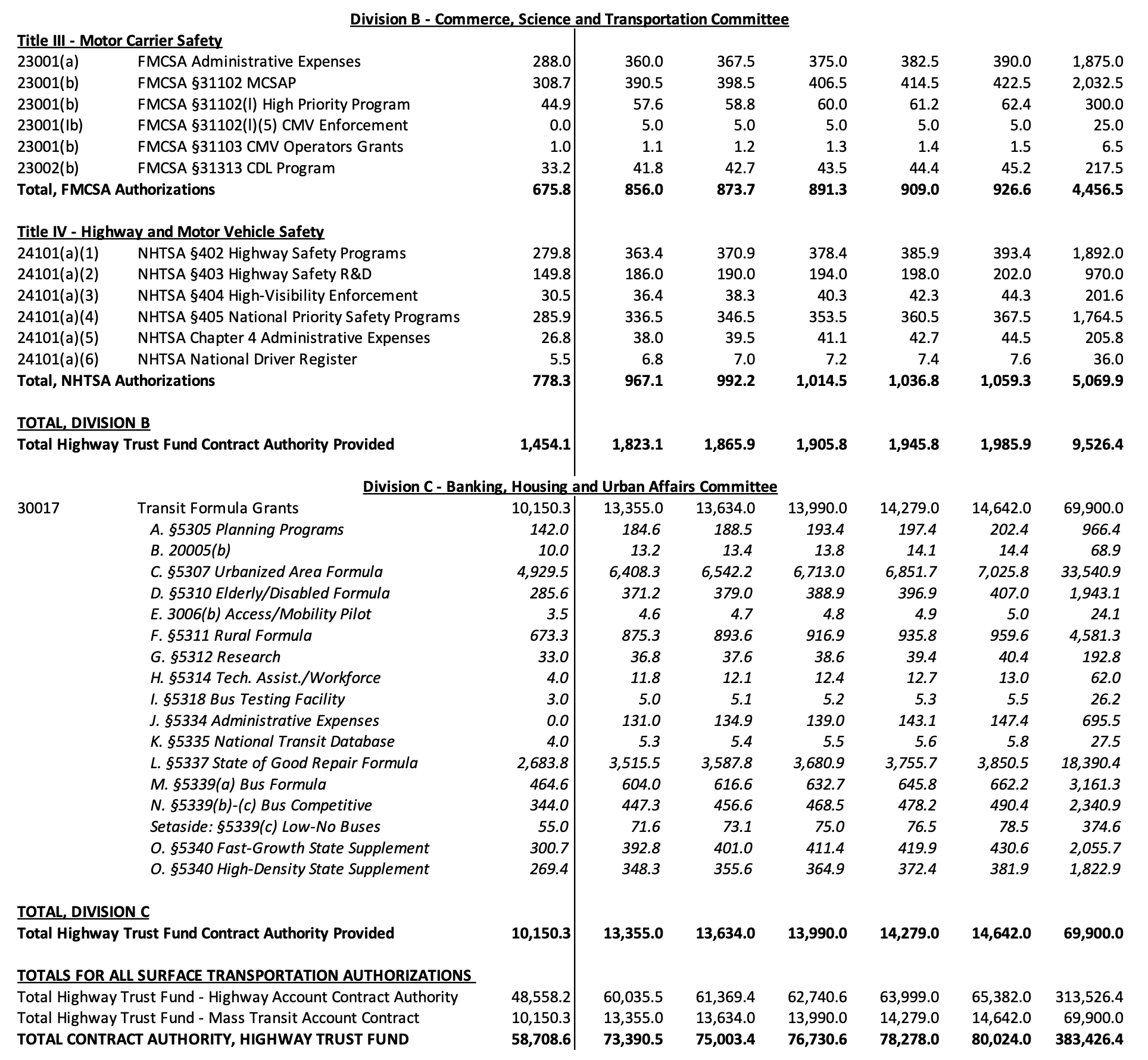

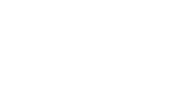

0.1 cent per gallon of the gasoline, diesel and special fuel taxes are not deposited in the HTF but instead are deposited in the Leaking Underground Storage Tank (LUST) Trust Fund. The remaining taxes are deposited in the Highway Trust Fund and allocated between the Highway Account and the Mass Transit Account as follows (per the February 2020 update to FHWA Table FE-21B):

Historical rates for federal taxes on motor fuel and lubricating oil can be viewed here, and historical rates for federal taxes on motor vehicles and related products can be viewed here.

Why is diesel taxed at a higher rate than gasoline?

Traditionally, the tax-writing committees of Congress have viewed the diesel fuel tax and the various trucking excise taxes holistically as an overall tax on trucking. The Highway Revenue Act of 1982 increased total HTF taxes significantly to pay for an expanded highway program and a new, permanent mass transit program, including increases in gasoline and diesel taxes from 4 cents per gallon to 9 cents per gallon. The tax rates in the law were set to try to match the costs incurred by various classes of highway user, per the results of the May 1982 DOT-Treasury Highway Cost Allocation Study.

The 1982 act also significantly increased the annual Heavy Vehicle Use Tax (HVUT) to recover the estimated wear-and-tear costs incurred by the heaviest trucks. This proved unpopular with truckers (particularly owner-operators, because the truck driver had to write his own very large check to the IRS). After hearings, Congress enacted the Deficit Reduction Act of 1984, which decreased the annual maximum HVUT from $1,900 to $550. At the time, the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) estimated that over five years, the HVUT reduction would cost the Treasury $2.1 billion in lost revenue, so the same law also increased the highway diesel tax rate by 6 cents per gallon, which JCT estimated would raise almost $2.2 billion in additional revenue over five years. Thus the overall revenues to the Trust Fund from the trucking sector would remain the same.

This 6-cent differential between the gasoline tax rate and the diesel tax rate remains in place to this day.

What other deposits are placed into the HTF?

Section 9503(b)(5) of the Internal Revenue Code provides that penalties relating to fuel tax evasion, and penalties collected for motor vehicle safety fines pursuant to 49 U.S.C. §30165, be deposited in the Highway Account of the Trust Fund.

In addition, section 9602 of the Internal Revenue Code requires that the balances of any federal trust fund account listed in chapter 98 (“Trust Fund Code”) of the IRC that is not required to meet current withdrawals be invested in “interest-bearing obligations of the United States.” The interest received from these investments is deposited in the Trust Fund. (The law in effect from October 1998 to March 2010 required HTF balances to be invested in non-interest-bearing securities.)

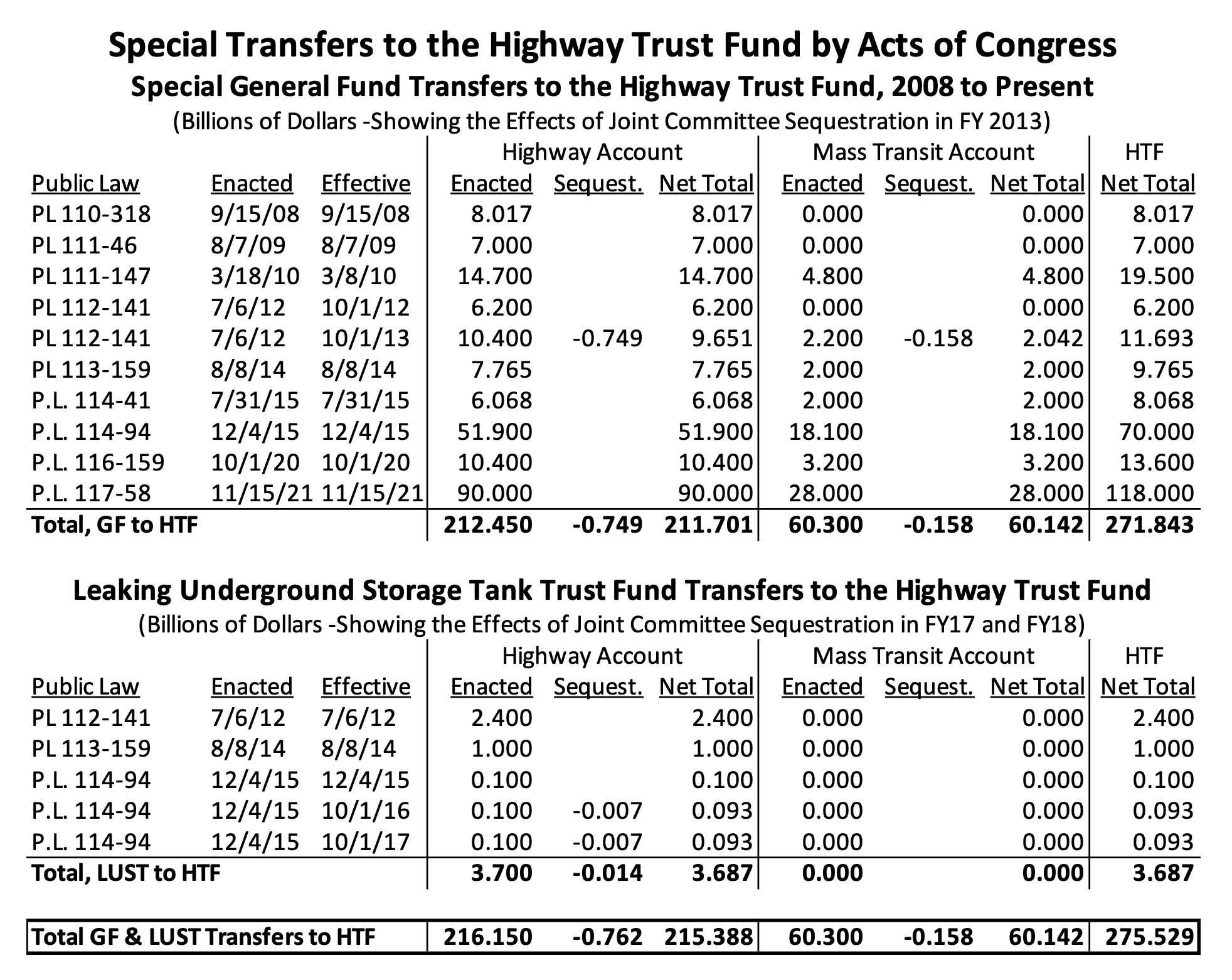

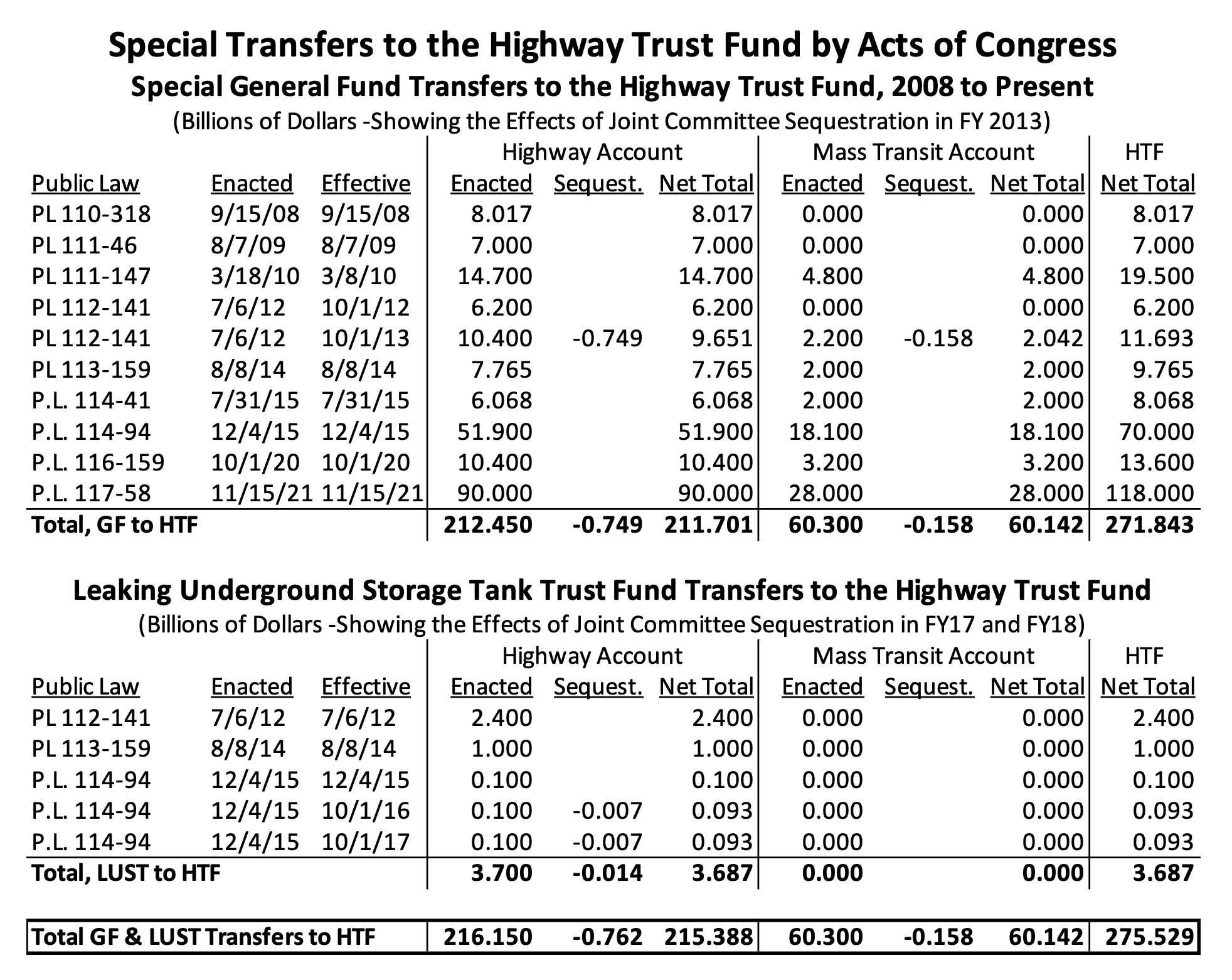

Congress has, on nine occasions from September 2008 through November 2022, enacted laws making special one-time transfers of funding into the HTF, totaling $275.5 billion (after budgetary sequestration – see Appendix B for a full list).

What taxes received by the HTF are then refunded elsewhere?

The Highway Revenue Act designed the HTF to collect taxes paid by highway users and hold them for eventual use for highway (and later, mass transit) spending to benefit those users.

Certain types of motor fuel use have traditionally been exempt from these taxes – farm use, school bus use, and use by state and local governments being chief among them. There have always been procedures whereby exempt users can apply for tax refunds or credits for federal motor fuel taxes paid at the pump (see chapter 2 of IRS Publication 510 for details).

From its inception through fiscal year 2011, the Trust Fund had to reimburse the general fund for the cost of these refunds and credits. For example, in fiscal year 2009, gross transfers of fuel taxes to the HTF totaled $33.95 billion, but the Trust Fund then had to transfer $1.05 billion back to the general fund to cover the cost of that year’s fuel tax exempt use refunds and credits.

After the HTF ran out of money in 2008, Congress enacted section 444 of the Hiring Incentives to Restore Employment Act of 2010, which shifted the burden of exempt use refunds and credits to the general fund. As a result, starting in fiscal year 2011, fuel tax refunds for exempt use are no longer reported in HTF operations – all such refunds are handled by the general fund.

What taxes received by the HTF are then transferred elsewhere?

As mentioned above, the purpose of the Highway Trust Fund is to segregate highway user taxes from general revenues and associate them with spending on programs that benefit those taxpayers.

But some people purchase gasoline or diesel at service stations, which has been taxed for highway use, and put that fuel in the tank of their motorboat, or their lawn mower or chainsaw, where it is not used on highways. So subsections 9503(c)(3) and (4) of the Internal Revenue Code provide that the estimated amount of taxes collected by the Highway Trust Fund from motorboat and small engine use then be transferred to the Sport Fish Restoration and Boating Trust Fund, with $1 million per year of that money also being set aside for transfer to the Land and Water Conservation Fund.

In addition, diesel fuel coming out of a refinery meant for highway use is so chemically similar to the kerosene used by jet and turboprop airplanes that there is always some overlap, so subsection 6427(l)(4) of the Internal Revenue Code requires regular transfers of estimated diesel taxes collected by the HTF but used in aviation to the Airport and Airway Trust Fund.

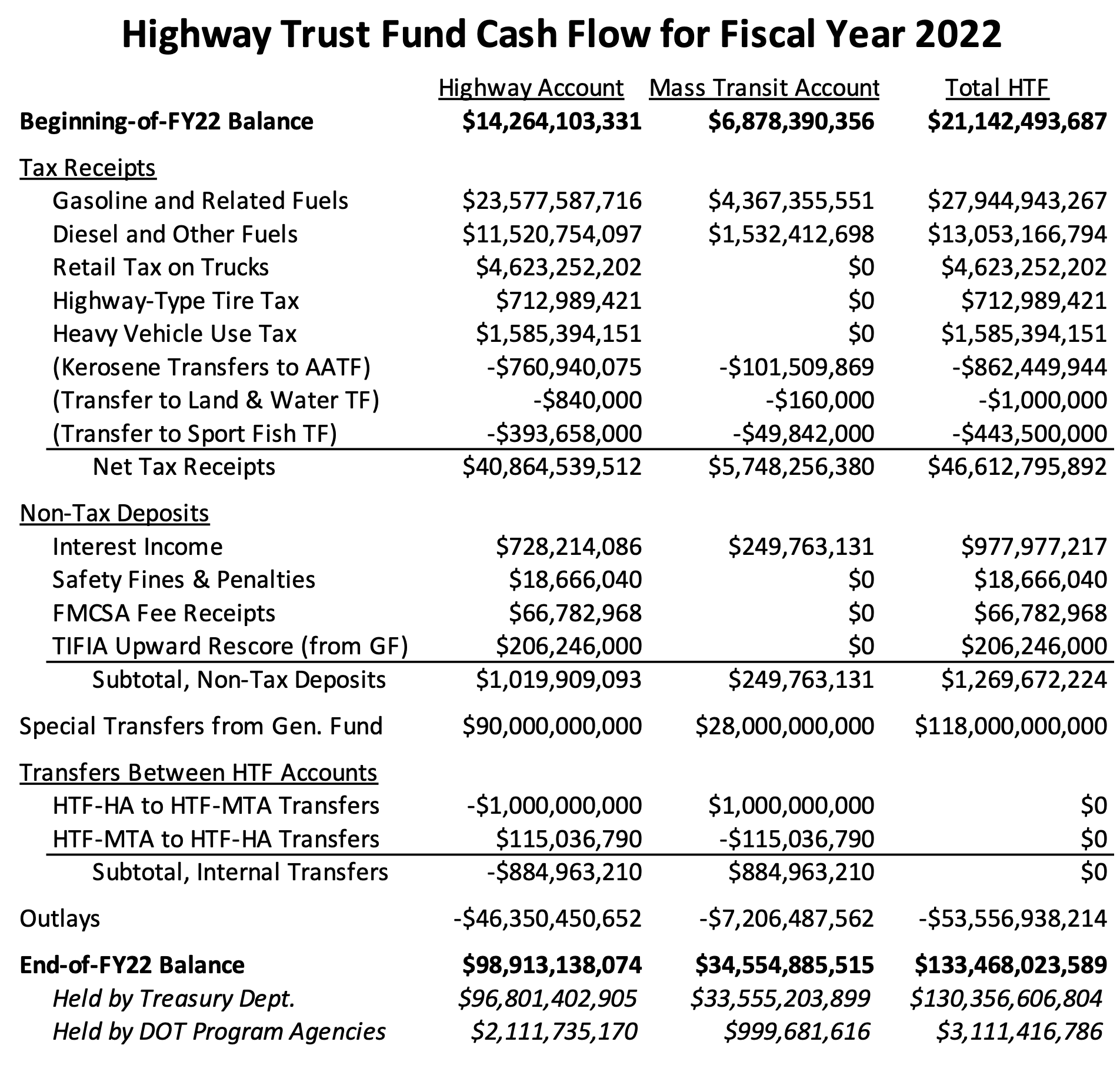

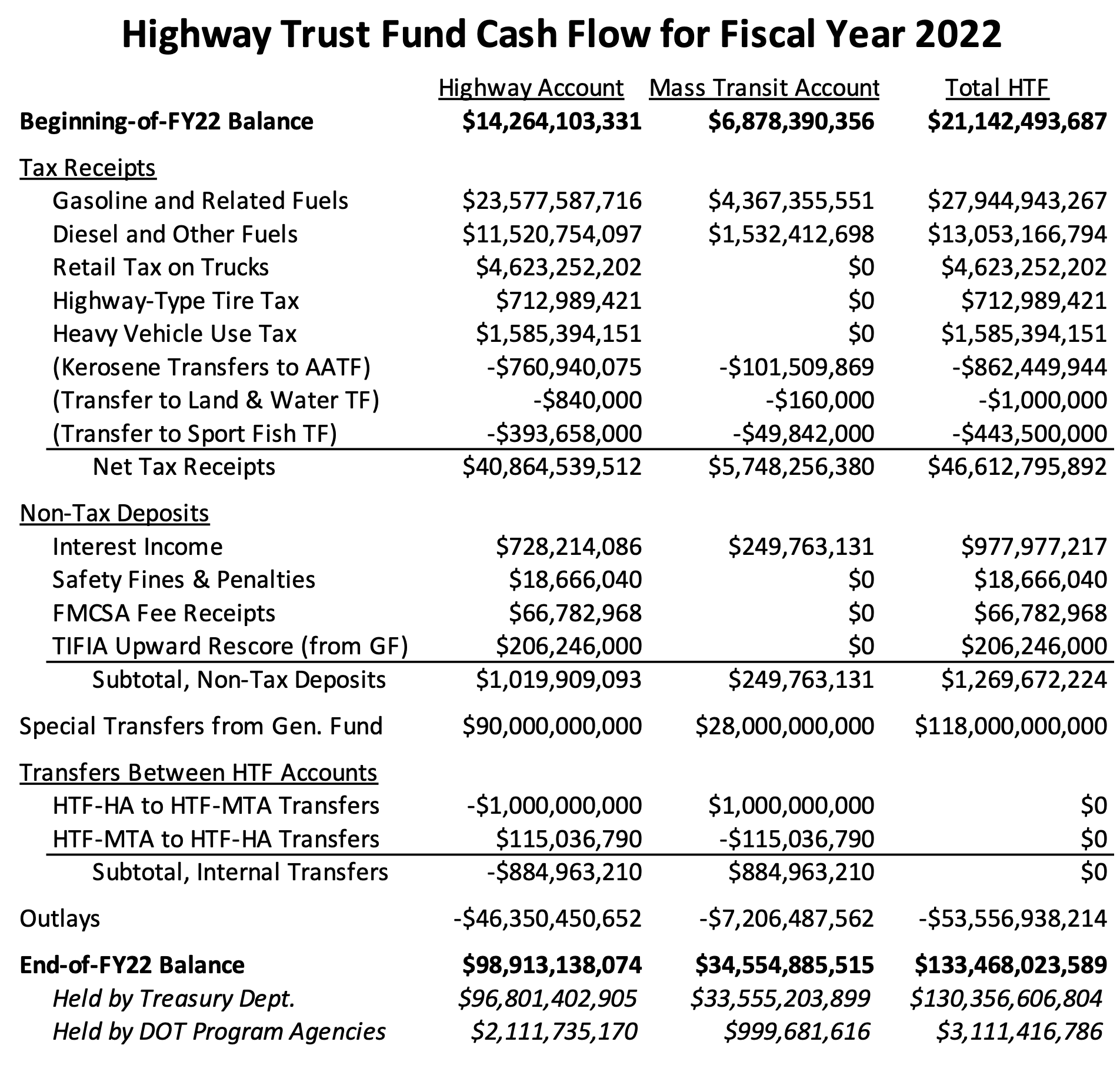

The amounts of such transfers in fiscal 2022 are shown in Appendix A.

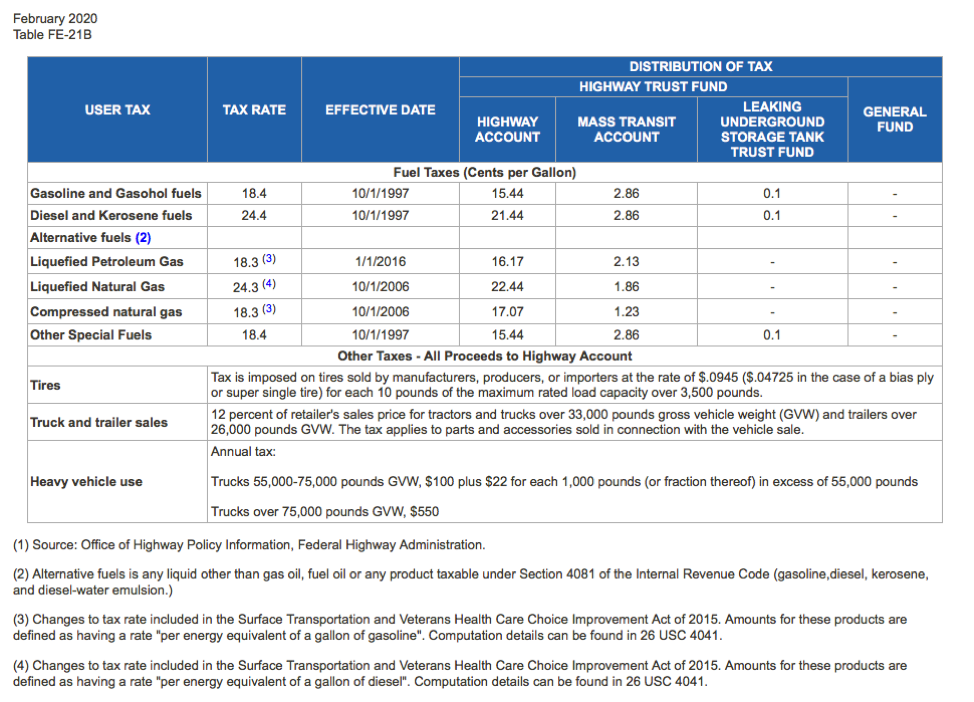

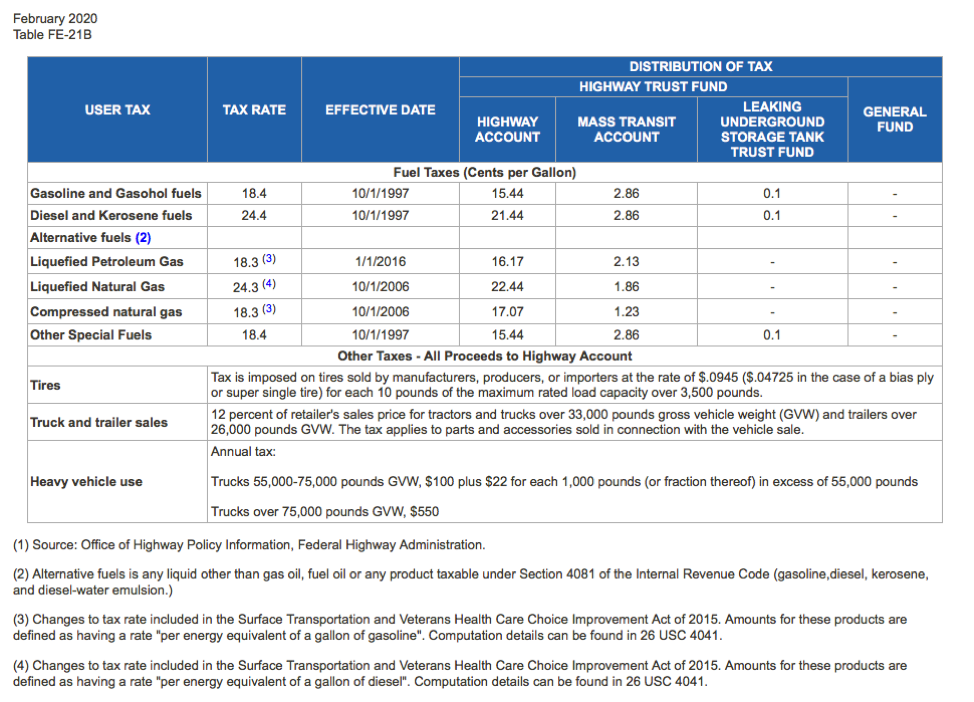

How reliant is the HTF on fuel taxes?

In the most recent fiscal year, net receipts from motor fuel excise taxes comprised 84 percent of net total deposits in the Highway Trust Fund.

A breakdown of the individual taxes and other revenue sources is shown in Appendix A.

What is the 80-20 highway-transit split?

After over a decade of debate in Congress, the Highway Revenue Act of 1982 struck a deal between urban interests and rural interests as to the future of the HTF. Urban legislators agreed to support a massive motor fuels tax increase (from 4 cents per gallon to 9 cents per gallon), in exchange for one penny of the nickel fuels tax increase being dedicated to a new Mass Transit Account within the Trust Fund. The Transit Account received 20 percent of the 1982 motor fuels tax increase, and after motor fuels taxes were increased in 1990 and 1993, when those tax increases were eventually transferred to the HTF, they were also split 80-20 between the Highway Account and the Mass Transit Account.

However, the entirety of the 4 cent per gallon pre-1982 gasoline and diesel tax rates, as well as all of the trucking industry excise taxes, are still deposited entirely in the Highway Account. As a result, the Mass Transit Account’s share of total Trust Fund tax revenue has never been close to 20 percent. The trucking excises in particular show a lot of volatility due to economic fluctuations (when the economy is good, trucking taxes have had a faster growth rate than fuel taxes of late), causing the ratio to shift every year. Over the last ten years (FY 2013-2022), the Transit Account has received, on average 12.6 percent of net total Trust Fund tax revenue (declining from 12.8 percent of total tax revenue in 2013 to 12.3 percent of total tax revenue in 2022).

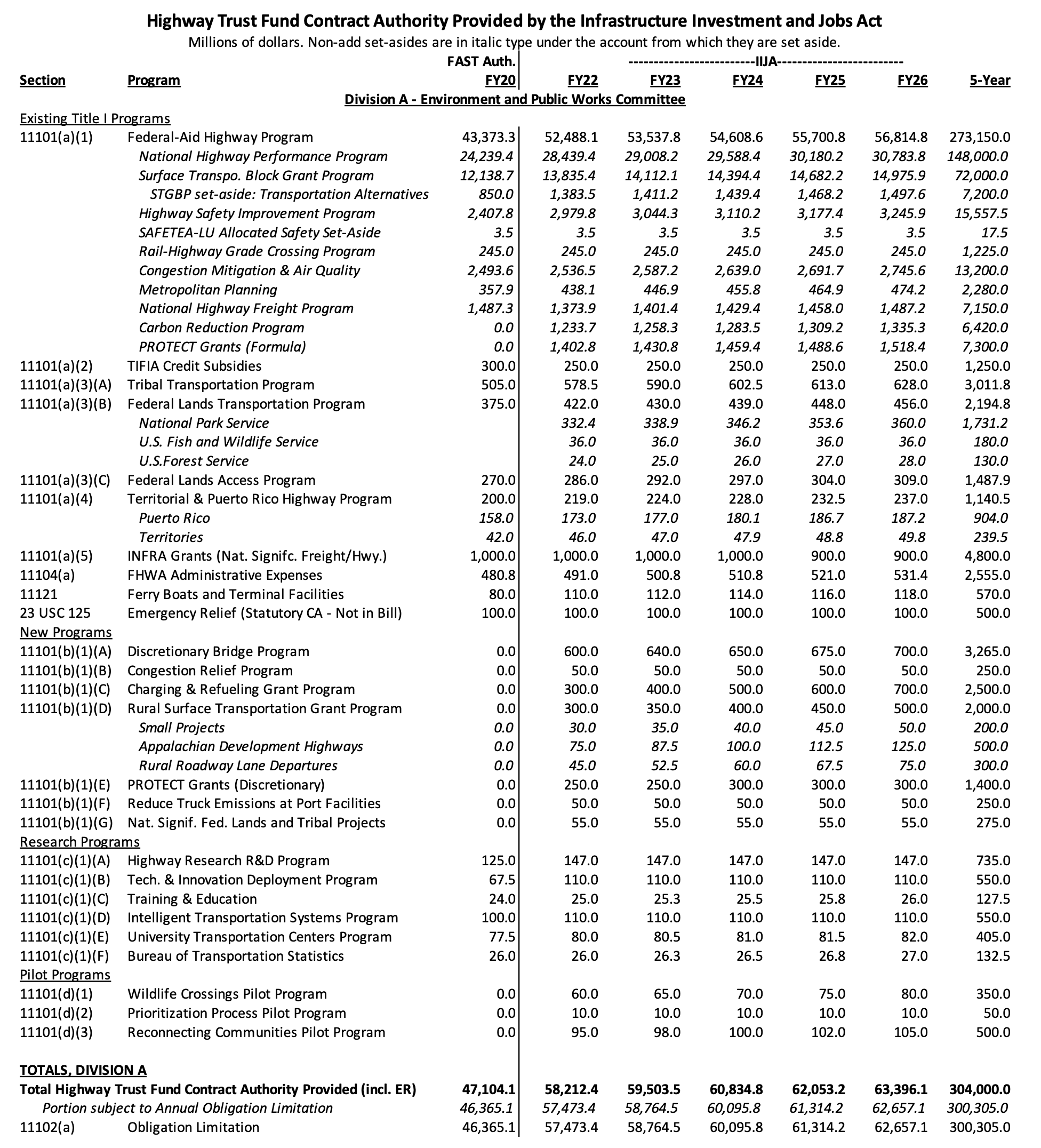

But while Transit Account tax revenues have been decreasing as a percentage of total revenues, Transit Account spending as a percentage of total Trust Fund spending has been increasing. In fiscal year 2015, the Transit Account received 16.9 percent of total Trust Fund contract authority. This increased to 17.4 percent of total Trust Fund contract authority over the five-year life of the FAST Act (2016-2020), and 18.2 percent of total contract authority over the five-year life of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (2022-2026). (See Appendix C.)

Because of this imbalance, the Mass Transit Account much more over-leveraged, relative to its dedicated tax revenues, than is the Highway Account, and needs a greater share of future tax revenues to remain solvent at current funding levels.

How does the Treasury Department collect and account for HTF revenues?

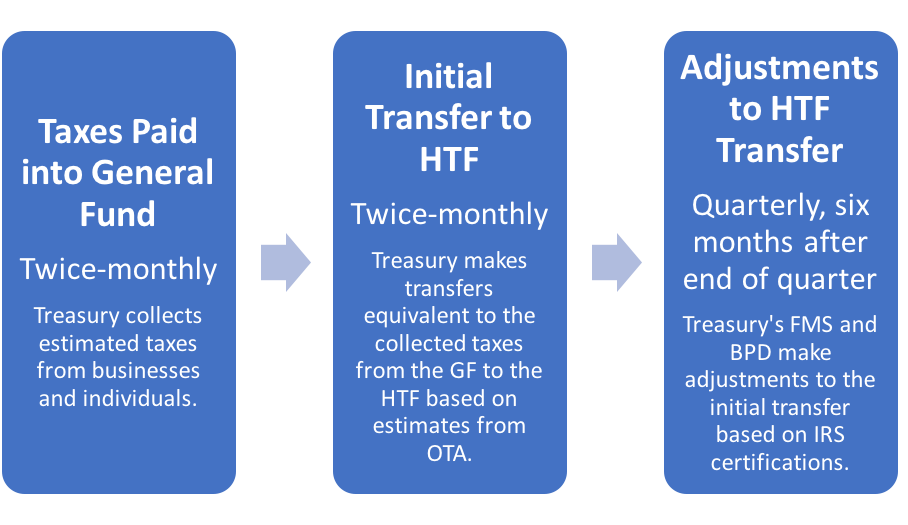

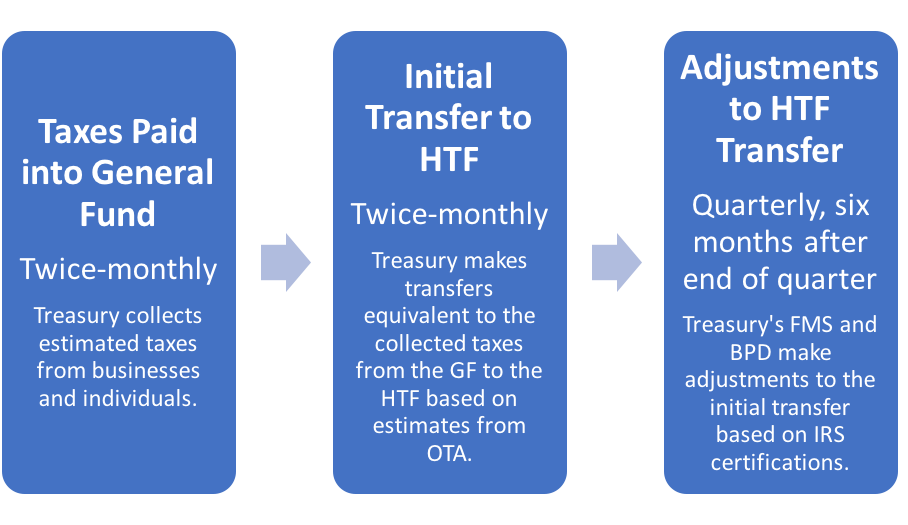

The following chart shows how estimated excise taxes are paid twice monthly into the general fund of the Treasury, and then transferred on an estimated basis to the HTF and later corrected based on a complicated set of estimations by the Treasury’s Office of Tax Analysis, Financial Management Service, Bureau of the Public Debt, and Internal Revenue Service.

These procedures are later audited by GAO (see their audit of the fiscal year 2019 transfer process here).

How are HTF tax payments attributed to states?

HTF excise taxes are usually not paid by the end consumer. Motor fuel taxes are paid by the oil company, when fuel is removed from the refinery or the tank farm (depending on ownership), and tire taxes are paid by tire manufacturers. Truck sales taxes are paid by the retailer, and the heavy vehicle use tax is paid annually by the truck owner.

As a result, as FHWA notes in Funding Federal-Aid Highways, “most of the Federal fuel taxes come from a handful of States (those where major oil companies are headquartered) and most tire taxes are paid from Ohio (the home of the U.S. tire industry).”

After the end of each fiscal year, FHWA estimates how much gasoline and diesel fuel was sold in each state “on the basis of data reported by State motor-fuel tax agencies” and estimates how much of the net gasoline, diesel and special fuel tax receipts for that year should be attributed to users in each state (and the District of Columbia). Then, FHWA allocates the receipts of the three trucking taxes for that year to states and D.C. in the exact same percentages as each state’s percentage of the estimated diesel fuel tax payments.

These yearly state tax estimates are then published by FHWA in Table FE-9 in the annual Highway Statistics series. The estimated state-by-state tax receipts for the Highway Account only are then used as a factor in the upcoming fiscal year’s highway funding apportionment calculations pursuant to 23 U.S.C. §104(c)(1)(B) to determine if any state’s total apportionment would be less than 95 percent of the dollar amount of its latest yearly estimated Highway Account tax payments. If any state requires such adjustment, they receive extra funding to get them to 95 percent of their most recent prior year dollar amount, and all other state-and-D.C. apportionments are reduced by pro rata shares of that amount. The only state that has triggered the 95 percent adjustment recently has been Texas.

There is a two-year lag in this cycle – a fiscal year ends on September 30, then FHWA makes the tax estimates a few months later, and then that data is used as a factor in apportionments made that summer for the fiscal year beginning October 1. So the estimated tax payments for fiscal year 2018 (which ended on September 30, 2018) were a factor in the highway apportionments for fiscal year 2020, which were calculated in late summer 2019 and apportioned on October 1, 2019.

FHWA publishes a cumulative total of total state estimated HTF Highway Account tax payments, and spending in each state from the Highway Account, cumulatively from 1956 in Table FE-221 in the annual Highway Statistics series.

What expenses are drawn on the HTF?

Section 9503 of the Internal Revenue Code provides strict limits on how funds can be withdrawn from the Highway Trust Fund. §9503(c)(1) and §9503(e)(3) provide that only funding specifically authorized to be appropriated from the Trust Fund by the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act of 2021, or a prior authorization law that was listed in section 9503 before the IIJA, can be removed from the Trust Fund. A table of IIJA Act authorizations can be found in Appendix C.

And §9503(b)(6) provides a “death penalty” of sorts if Congress appropriates funds from the HTF not authorized by the FAST Act or prior authorization laws – after the date of any such unauthorized expenditure, the Trust Fund may no longer receive transfers of tax collections from the general fund of the Treasury.

Prior to 2005, the Appropriations Committees had a blanket authorization to appropriate funds from the HTF for the highway emergency relief program, as emergencies arose, in such amounts as they saw fit, but this authorization has since been repealed.

How are funds transferred between HTF accounts?

23 U.S.C. §133 and 23 U.S.C. §149 allow funds provided from the Highway Account for the Surface Transportation Block Grant Program and the Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality Program, respectively, to be used for mass transit projects in some instances. And the definition of a mass transit capital project in 49 U.S.C. §5302 includes some highway elements, which allows funds provided from the Mass Transit Account to be used for highway projects in some instances.

Accordingly, 23 U.S.C. §104(f) and 49 U.S.C. §5334(i) allow those “flex” funds to be transferred from FHWA to FTA (or vice versa) for program administration, and from the Highway Account to the Mass Transit Account (or vice versa) for eventual expenditure.

In fiscal year 2022, transfers from the Highway Account to the Mass Transit Account pursuant to these authorities totaled $1.000 billion, and transfers from the Mass Transit Account to the Highway Account totaled $115 million, for a net HA to MTA transfer of $885 million.

The amounts of such transfers cannot be predicted in advance with any precision because they are the result of many decisions made on a project-by-project basis by state and local authorities.

Congress also retains the ability to pass a law at any time transferring money from one account to another.

What is the HTF balance?

The balance of the Trust Fund is the cumulative excess of all deposits since its inception, minus cumulative outlays and a one-time balance writedown on October 1, 1998. This balance is held in several places – the bulk of it (the “corpus”) is held by the Treasury Department, and almost all of that is invested in special Treasury securities created as needed for that purpose. But the various Department of Transportation modal administrations that are responsible for actually spending the money withdraw sums from the corpus in anticipation of immediate future needs and hold it on their own books until the money is eventually disbursed.

The present practice (as of August 2023) is for the Treasury to create special one-day-maturity securities each business day and invest its the Trust Fund balance overnight, only to redeem those securities the next business day and then start the process all over again. For example, on July 31, 2023, Treasury redeemed $120.829 billion in securities paying an annualized rate of 5.38 percent, deposited that money in the Trust Fund, paid itself $54 million in interest and deposited that in the Trust Fund as well, and then at the end of the day, purchased new one-day securities for $120.883 billion that paid an annualized rate of 5.37 percent.

Because the total balance is held by multiple agencies, the monthly Treasury reports on Trust Fund operations can be misleading – they are accurate on the receipt side, but on the spending and balance side, they only show the withdrawals made by program agencies (not actual outlays) and the balance of the corpus (not the other balances held by program agencies).

Why are positive cash balances necessary?

As mentioned above, estimated taxes are deposited in the Trust Fund twice a month. But outlays are drawn from the Trust Fund every business day. At the peak of warm-weather construction season (August through October), these outlays can exceed $300 million per business day. It is therefore possible for an account in the Trust Fund to run out of money on a day-to-day basis during a month yet still be solvent at the end of a month because of the end-of-month deposit of tax revenue.

In addition, there is a special problem at the end of every fiscal year. Because the IRS collects estimated taxes based on past business activity (the mid-month IRS collection of estimated excise taxes covers business activity in the last two weeks of the prior month), the end of every fiscal year has to be reconciled. Accordingly, the Trust Fund only receives one tax payment every September (mid-month), and then has to wait an entire month for a massive, double-sized payment in mid-October that is then retroactively credited to the fiscal year that ended September 30. And then the tax collection calendar resets.

In essence, every September the Trust Fund gets credited with six weeks of tax money, but four weeks’ worth of that doesn’t get deposited until mid-October. Then October is only credited with two weeks of tax revenue. These are the actual results from a typical year:

|

August 2019 |

September 2019 |

October 2020 |

| HTF Net Tax Rev. |

$3.222 billion |

$6.801 billion |

$874 million |

Since this happens at the height of warm-weather construction season, when the Trust Fund has its highest daily spending rate, extra balances are necessary to get through September and October without running out of money.

Because of the day-to-day and year-end problems, DOT estimates that Congress needs to plan on projected year-end balances (including the mid-October retroactive payment) never dipping below $4 billion in the Highway Account and $1 billion in the Mass Transit Account to avoid day-to-day insolvency during September-October.

Positive balances are also necessary to prevent automatic reductions in Trust Fund contract authority under the Byrd and Rostenkowski tests (see below).

What happens when the HTF runs out of money?

The Impoundment Control Act of 1974, as interpreted by several federal courts, prevents the executive branch of the federal government from withholding HTF contract authority that has been made available for obligation by law, even when it is apparent that there will not be money in the Trust Fund to liquidate the contract authority. Without special legislative approval, the Administration cannot prevent states and transit agencies from incurring obligations drawn on the HTF and presenting bills for liquidation of those obligations.

When HTF balances drew low in summer 2014, the Secretary of Transportation wrote a letter to all state DOTs saying that “as we approach insolvency, the Department will be forced to limit payments to manage the reduced levels of cash available in the Trust Fund. This means, among other things, that the Federal Highway Administration will no longer be able to make ‘same-day’ payments to reimburse States.”

The Secretary’s letter indicated that states would be notified twice a month of the amount of highway reimbursements they would be allowed to have repaid during that period, which would be the amount available in the HTF (after one of the twice-monthly tax deposits from the Treasury) times each state’s share of total apportioned federal highway funding for that year.

The HTF was bailed out by another special transfer before the Department had to put those plans into effect, but similar plans will likely be put into place the next time the HTF runs critically low on balances. And were such a system to remain in place for some time, the total amount of unpaid bills would keep piling up.

What are the Byrd and Rostenkowski amendments (tests)?

The Byrd amendment (now 26 U.S.C. §9503(d)), generally referred to as the Byrd test, was put in place by Senate Finance Committee chairman Harry Byrd (D-VA) in 1956 to require that the Highway Trust Fund have enough liquid revenue to pay its funding commitments. The Byrd amendment ensures that Highway Account commitments are compared to projected financial resources. If insufficient resources are identified in the HTF, per the Byrd amendment, across-the-board cuts are required to be made in Federal-aid highway apportionments. The resources in the Byrd amendment calculation consist of the current Highway Account balance plus estimated income for the next 4 years. These resources are then compared to the unliquidated authorizations of the Highway Account.

From 1957 to 2005, the Byrd amendment calculation was measured against current balances plus 2 subsequent years of income, not 4 years. Over that period, The Byrd Amendment was triggered twice resulting in the reduction in the Interstate System construction apportionments for FY 1961 and of all highway apportionments for FY 2004. The 2005 SAFETEA-LU law increased the Byrd test “window” from 2 years of future revenues to 4 years or future revenue, ensuring that the Highway Account could hit a zero balance before the Byrd test would automatically reduce spending (which happened in 2008).

The Mass Transit Account is subject to a similar test known as the Rostenkowski test (26 U.S.C. §9503(e)(4). The Rostenkowski test originally measured outstanding commitments against estimated income for one year. The 1998 TEA-21 law amended the Rostenkowski test so that the Mass Transit Account is subject to the same 2-year test as the Highway Account, and then the 2005 SAFETEA-LU law set the window for both accounts at 4 years. The March 2019 Treasury Bulletin indicated that the Mass Transit Account was going to fail the Rostenkowski Test for fiscal 2020, which would result in across-the-board reductions of about 12 percent in mass transit apportionments.

Congress then enacted section 144 of Public Law 116-59 just before the start of fiscal year 2020 to temporarily suspend application of the Rostenkowski Test, and later enacted section 163 of Division H of Public Law 116-94 to cancel the application of the Rostenkowski Test for the remainder of fiscal 2020. Every annual DOT appropriations act since then has contained identical language suspending the application of the Rostenkowski Test for an additional fiscal year.

What other kinds of HTF spending control are available?

From the late 1950s through 1975, Presidents routinely limited the amount of existing highway contract authority that could be obligated by states during a specific period (sometimes a fiscal quarter, sometimes a fiscal year). The enactment of the Impoundment Control Act of 1974 severely restricted the President’s ability to withhold contract authority, so Congress began enacting “obligation limitation” provisions in the annual transportation appropriations acts that performed the same functions.

Over the 1976-2011 period, annual obligation limitations for the highway program were usually below the level of new contract authority, sometimes significantly so. Beginning with the MAP-21 law, the authorizing and appropriating committees of Congress have worked to ensure that every dollar of new contract authority subject to limitation is matched with one dollar of new obligation limitation. However, this could change in the future, and the obligation limitations in the appropriations bills could become a point of HTF spending control once again.

Why don’t the Fiscal Responsibility Act’s spending caps or sequestration affect HTF spending?

Contract authority is a form of budget authority that is classified as mandatory. But the eventual release of cash from the HTF to liquidate contract authority (the outlays) is technically controlled, for the most part, by the Appropriations Committees through the annual obligation limitation and is thus classified as discretionary. The HTF contains the only accounts in the entire federal budget (save the Airport Improvement Program) that are split-classified in this way, with the budget authority being on the mandatory ledger and the outlays on the discretionary ledger.

The current statutory budget enforcement regime has two different control systems. The control system for mandatory spending (PAYGO) is only triggered by changes in mandatory outlays, not budget authority – and HTF outlays are discretionary. The control system for discretionary spending (the spending caps under the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023) only affects budget authority, not outlays – and HTF contract authority is mandatory budget authority. Because of this discrepancy, HTF contract authority, obligation limitations, and outlays are effectively exempt from both budget control systems.

Sequestration (across-the-board percentage cuts in certain programs) is a tool used to enforce both budget control systems (PAYGO and the spending caps), but since the HTF accounts are exempt from both control systems, the HTF accounts are also almost entirely exempted from sequestration.

(A small amount of annual highway contract authority – currently $739 million per year – is exempt from the annual obligation limitation. Its outlays are thus classified as mandatory and so that contract authority is subject to budget sequestration.)

Wasn’t the HTF supposed to be at least 90 percent self-sufficient?

One of the main purposes of the Congressional Budget Act of 1974 was to restrict the ability of Congress to create new “backdoor spending” (programs funded outside of the annual appropriations process). Section 401 of that law contains an internal prohibition within Congress against bringing up legislation creating new backdoor spending – including contract authority – unless grandfathered into the Social Security or Medicare Trust Funds or unless the money is drawn “from any other trust fund, 90 percent or more of the receipts of which consist or will consist of amounts (transferred from the general fund of the Treasury) equivalent to amounts of taxes (related to the purposes for which such outlays are or will be made)…” The 90 percent threshold was established in a Senate floor amendment to the Budget Act in 1974 by Sen. Sam Nunn (D-GA) (by an 80 to 0 vote – see pages 7921-7923 here).

However, the prohibition in section 401 only applies inside Congress and is cumbersome to use. Even if a Member of Congress raises a point of order, it can be waived by a simple majority vote of the House and Senate. And unlike PAYGO or the Byrd test or sequestration, there is no automatic enforcement procedure for section 401 outside the halls of Congress. As a result, Congress has ignored or waived the 90 percent self-sufficiency point of order when considering every bill providing HTF spending since at least 2005, and the Trust Fund has become reliant on special transfers from the general fund that exceed 10 percent of its annual revenues.

Appendix A – Fiscal year 2022 Highway Trust Fund operations (cash flow)

Appendix B – List of all special transfers to the Highway Trust Fund, 2008-2021

Appendix C – Authorizations for Highway Trust Fund spending in the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act of 2021