September 30, 2016

Only four Democrats voted against the Water Resources Development Act in the House of Representatives this week on final passage. But one of them was Rep. Peter DeFazio (D-OR), the ranking minority member of the Transportation and Infrastructure Committee and co-author of the bill.

DeFazio was so irate that the Republican leadership had stripped his provision from the bill that would have allowed all balances in the Harbor Maintenance Trust Fund to be spent as fast as the Corps of Engineers can spend it starting in fiscal 2027, he even took the unusual (for a senior T&I leader) step of trying to kill one of the projects in the bill belonging to another member.

This is one of those situations where DeFazio is largely correct on substance but is deeply, perhaps irreparably, disadvantaged on process. And as DeFazio’s former colleague John Dingell (D-MI) once memorably said, “If you let me write the procedure, and I let you write the substance, I’ll screw you every time.”

The Harbor Maintenance Trust Fund (HMTF) was created in 1986 to help fund port and harbor dredging activities of the Corps of Engineers. The Trust Fund is funded by the Harbor Maintenance Tax (HMT), a tax of 0.125 percent of the value of commercial cargo loaded on or unloaded from a commercial vessel at a harbor or port at which federal funds have been used since 1977 for construction, maintenance or operation. (A list of those ports is in the implementing regulations, here.)

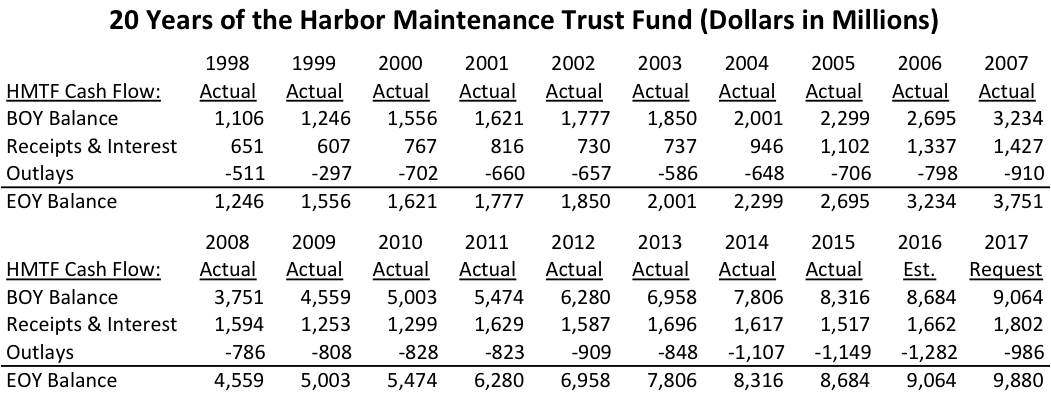

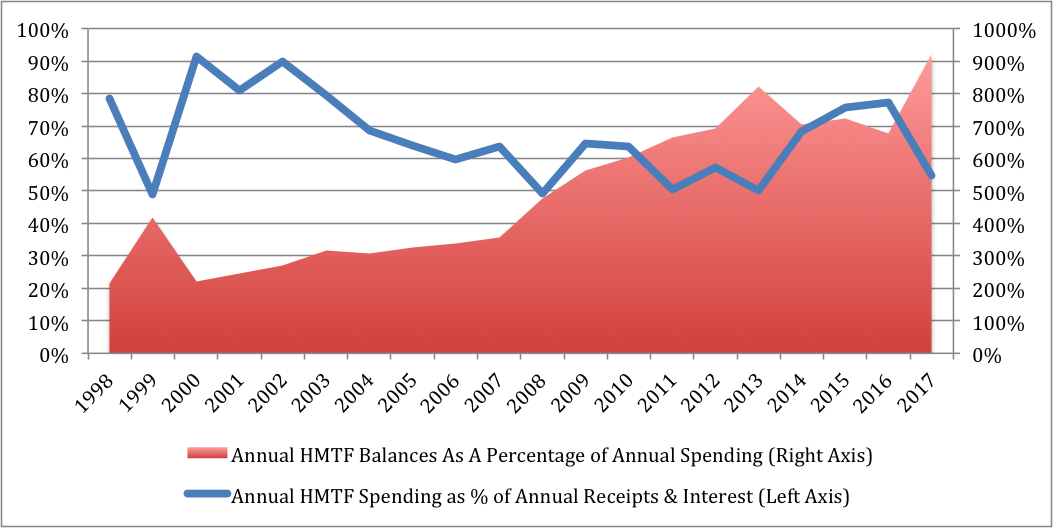

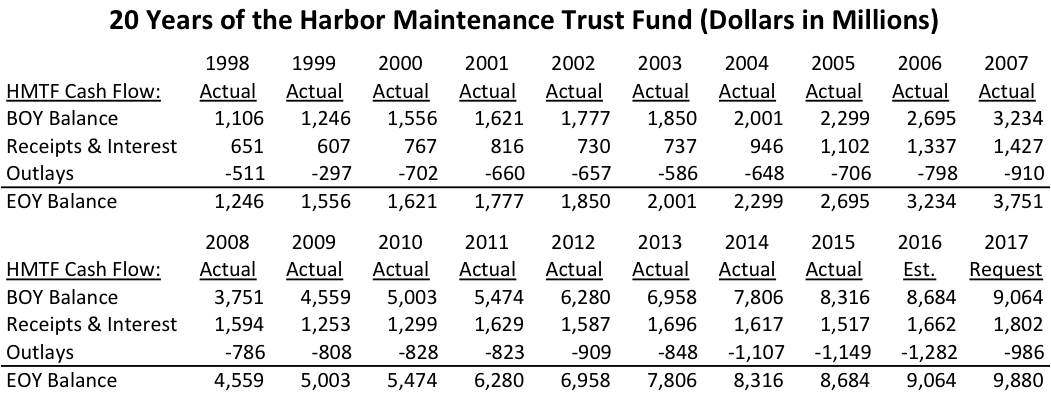

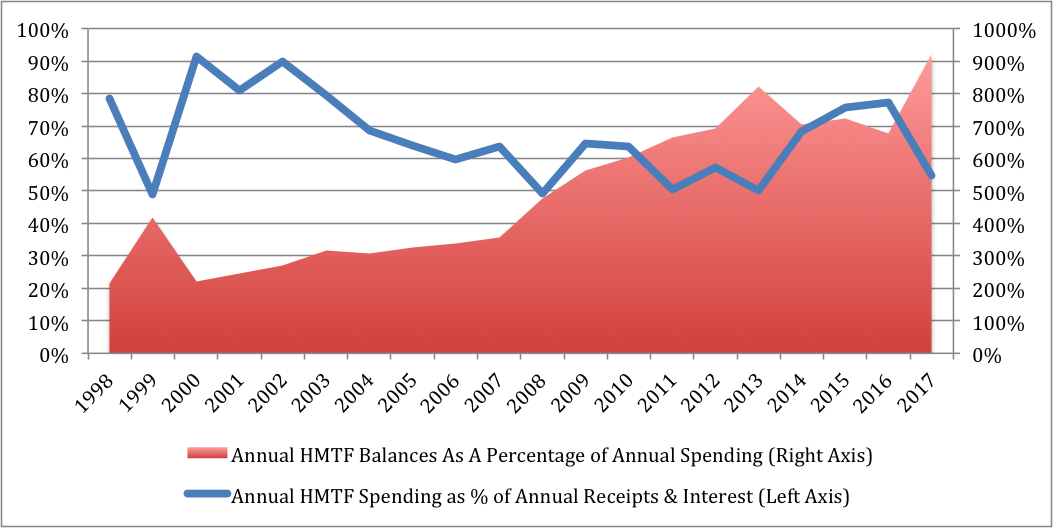

Over the last 20 years, annual HMT receipts have soared, due in large part to the increase in trade since China joined the World Trade Organization in 2001. When combined with interest on balances, HMTF proceeds have tripled in nominal terms since 1999. But spending from the HMTF is controlled via the annual appropriations process and has not kept up with tax receipts. This is due to a variety of reasons, including institutional dislike for the Corps water program by the White House budget office, the need to balance competing interests for scarce federal dollars, but most importantly the post-2011 spending caps under the Budget Control Act.

For example, the Budget Control Act limits all non-defense discretionary appropriations in fiscal 2017 to no more than $518.5 billion. If appropriations exceed that amount, another round of sequestration is ordered and all accounts are reduced pro rata until the total is down to the cap level.

The Budget Control Act is completely indifferent as to the source of an appropriation. It doesn’t matter whether the appropriation is drawn from a user-supported trust fund with a $9 billion unobligated balance like the HMTF or drawn from direct borrowing from China in the international bond market. Every non-defense discretionary dollar is alike, and they are all fungible between the Corps of Engineers, the FAA, Amtrak, mass transit, HUD, the EPA, the Justice Department, and all the rest of the annual discretionary budget.

DeFazio tried to get around this and other budgetary pressures by adding what was section 108 to the WRDA bill, which declared that on October 1, 2026, all unobligated balances in the HMTF would immediately be appropriated and could be spent on harbor projects as fast as the Corps could spend the money. The Congressional Budget Office estimated this would exceed $20 billion, but because it would occur the day after the current budget scorekeeping window closes, for the purposes of most budget enforcement the $20 billion appropriation does not exist.

By making the automatic-spending provision take effect on the day after the ten-year budget scorekeeping window closes, DeFazio was, in essence, copying the Mother of All Budget Gimmicks. In 1987, when the Gramm-Rudman-Hollings law forced Congress to pay strict attention to the annual deficit lest sequestration take effect, Congress passed a law that moved the payday for the armed forces from September 30, 1987 to October 1, 1987. That one-day, one-time delay moved $3 billion in outlays from fiscal year 1987 to 1988. But even though it lowered the FY 1987 deficit by $3 billion, it didn’t really save the taxpayers a dime.

House Speaker Paul Ryan (R-WI), former chairman of the Budget Committee, no doubt had this in mind when he sided with Appropriations chairman Hal Rogers (R-KY) and Budget chairman Tom Price (R-GA), who wanted to protect their jurisdiction and strike DeFazio’s provision from the bill.

But if DeFazio’s approach was a bit too clever, his underlying point is quite valid – port interests are being taxed for port maintenance but most of the proceeds of the tax are not being spent. Instead, they are being banked in the HMTF in the form of government IOUs while the tax dollars themselves (fungible with the rest of federal dollars in the Treasury) are spent on other things.

How can this problem – the complete lack of any relationship between HMT receipts and HMTF spending – be solved?

To begin with, advocates of federal spending programs funded by dedicated excise taxes on system users, like highways, aviation, and Corps of Engineers harbor programs, often refer to those excise taxes as “user fees” in the hope that by calling a tax something other than a tax, Congress will find the political will to vote for a tax increase that can fund a spending increase. Those advocates should stop calling taxes fees because it can be counterproductive, especially so for the HMTF. (Ed. Note: the federal HMT regulations themselves call it a fee, not a tax – see here.)

“User fee” has a specific meaning in the Constitution and in law. Under the Constitution, the Senate cannot originate taxes, but it can originate user fees. Nor can taxes be levied on exports – but user fees can be. There is a body of federal case law on this issue and a much larger body of Congressional precedents where the House of Representatives has sent back bills to the Senate for overstepping its constitutional bounds.

The difference is particularly pronounced where the Harbor Maintenance Tax is concerned, because a unanimous U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1998 (Notorious RBG wrote the opinion) that the HMT is a tax and not a user fee. The Court’s holding in that case (U.S. v. United States Shoe Corp.) is still controlling:

…the Export Clause categorically bars Congress from imposing any tax on exports. The Clause, however, does not rule out a “user fee,” provided that the fee lacks the attributes of a generally applicable tax or duty and is, instead, a charge designed as compensation for Government-supplied services, facilities, or benefits…

The HMT bears the indicia of a tax. Congress expressly described it as “a tax on any port use,” 26 U. S. C. § 4461(a) (emphasis added), and codified the HMT as part of the Internal Revenue Code… The crucial question is whether the HMT is a tax on exports in operation as well as nomenclature or whether, despite the label Congress has put on it, the exaction is instead a bona fide user fee…

…the connection between a service the Government renders and the compensation it receives for that service must be closer than is present here…the HMT is determined entirely on an ad valorem basis. The value of export cargo, however, does not correlate reliably with the federal harbor services used or usable by the exporter. As the Federal Circuit noted, the extent and manner of port use depend on factors such as the size and tonnage of a vessel, the length of time it spends in port, and the services it requires, for instance, harbor dredging.

…we must hold that the HMT violates the Export Clause as applied to exports. This does not mean that exporters are exempt from any and all user fees designed to defray the cost of harbor development and maintenance. It does mean, however, that such a fee must fairly match the exporters’ use of port services and facilities.

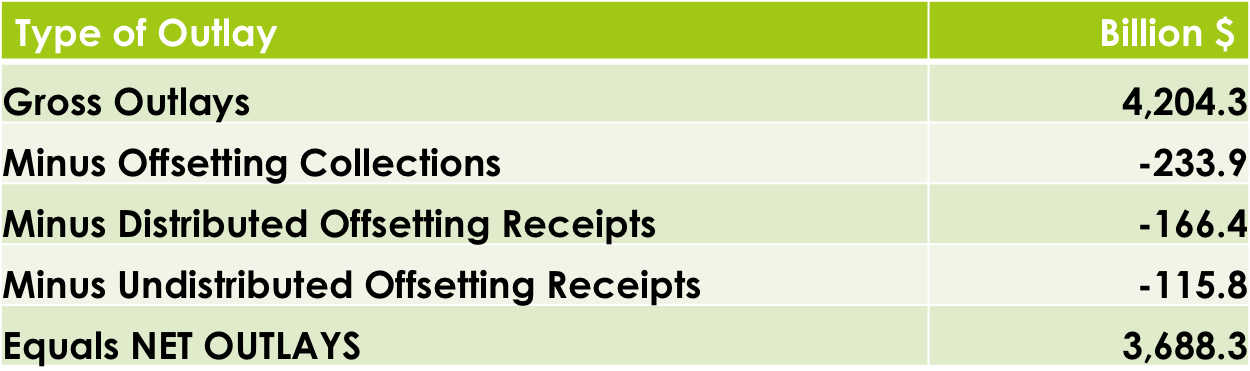

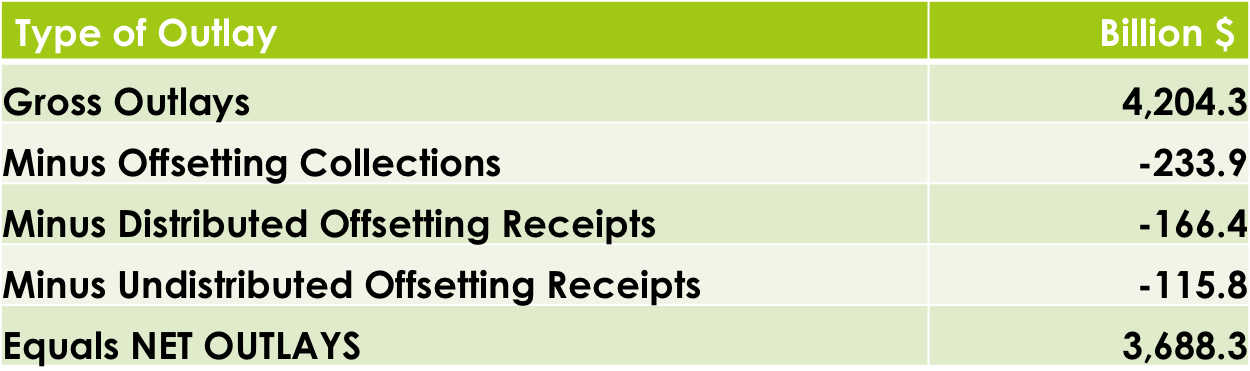

Why does the tax versus fee distinction matter? Because under the system of budget concepts adopted by the federal government 50 years ago, “real” user fees are recorded on the spending side of the budget as negative spending. Taxes are recorded on the receipt side of the budget. In the context of our current situation, where the Budget Control Act limits discretionary appropriations each year (enforced by automatic sequestration if appropriations exceed the annual cap), real user fees can be used to automatically offset appropriations and help Congress stay under the spending caps, while excise taxes cannot.

A good example of a real user fee is the aviation security fee instituted after 9/11 (in a bill that was originated in the Senate, not the House). Every dime of the security fee collected between 2001 and 2013 was recorded as negative spending (a “discretionary offsetting collection”) and applied directly to the annual TSA appropriation, reducing the net appropriations total substantially. (Congress increased the fee in 2013 and applied some of it to deficit reduction on the mandatory side of the spending ledger as an “offsetting receipt” instead of to the the TSA appropriation, but it’s still negative spending.)

As such, balances cannot be built up, and every dime of a real user fee that comes in can be spent immediately without worrying about spending caps.

Congress created the HMT 30 years ago in lieu of a system of user fees because, at the time, a simple ad valorem tax was much easier to administer. With the advent of computers, it would not be that difficult today to design a system of real user fees on port imports and exports that actually does “correlate reliably with the federal harbor services”. Replacing the HMT with real user fees that are recorded in the budget as negative spending would permanently fix the problem of mismatched user revenues with user services. (It would not, however, address the problem of the $9 billion to date collected from the HMT but not spent by the HMTF.)

Alternatively, if Price and Senate Budget chairman Mike Enzi (R-WY) are successful in setting up a new budget concepts commission, one of the areas that commission could address would be reform of the way that user-financed trust fund accounts are budgeted, which might also make it easier to spend receipts from the existing HMT.

FY 2015 Federal Spending – Gross vs. Net

“Offsetting Collections” are user fees applied as negative spending against a specific appropriations account. “Distributed Offsetting Receipts” are user fees applied as negative spending against a particular department, bureau, agency or budget subfunction. “Undistributed offsetting receipts” are user fees that are applied as negative spending against the entire federal budget.