September 8, 2017

One of the issues that has arisen regarding the proposal made by House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee Chairman Bill Shuster (R-PA) to spin off air traffic control (ATC) provision into a non-profit entity is how the new entity will be governed. Supporters of the bill say that this will be a user co-op like is common among utilities. Critics argue that the new system will be dominated by the large airlines. In this article we’ll provide an overview of the proposed governance model, and how it has been implemented by the Canadians in their own nonprofit ATC provider, NAV CANADA.

The governance of the new entity, the American Air Navigation Services Corporation, is outlined on Title II, Chapter 903, sections 90306 and 90307 of the “21st Century Aviation Innovation, Reform, and Reauthorization Act”. Section 90306 outlines the structure of the Board of Directors and section 90307 discuss the directors’ fiduciary duties to the corporation.

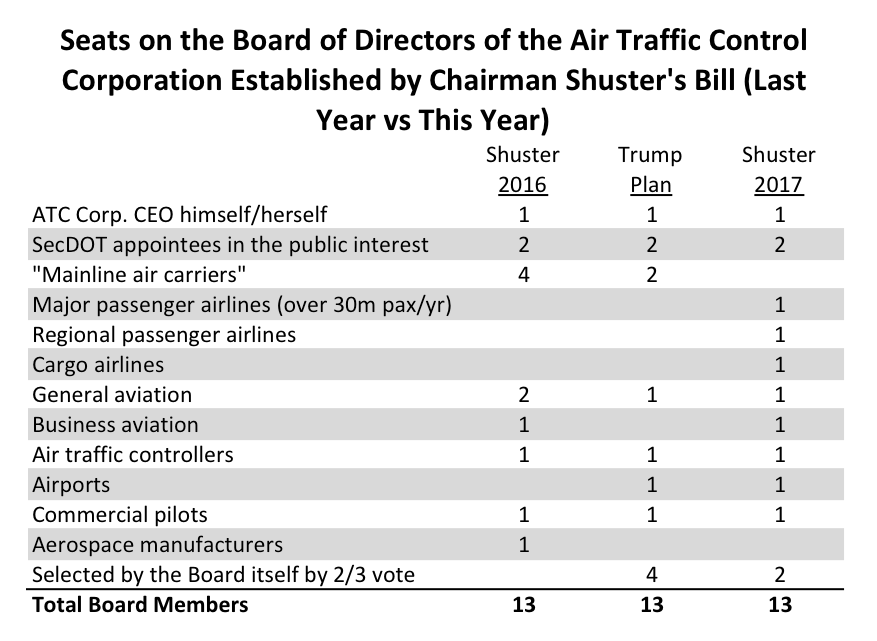

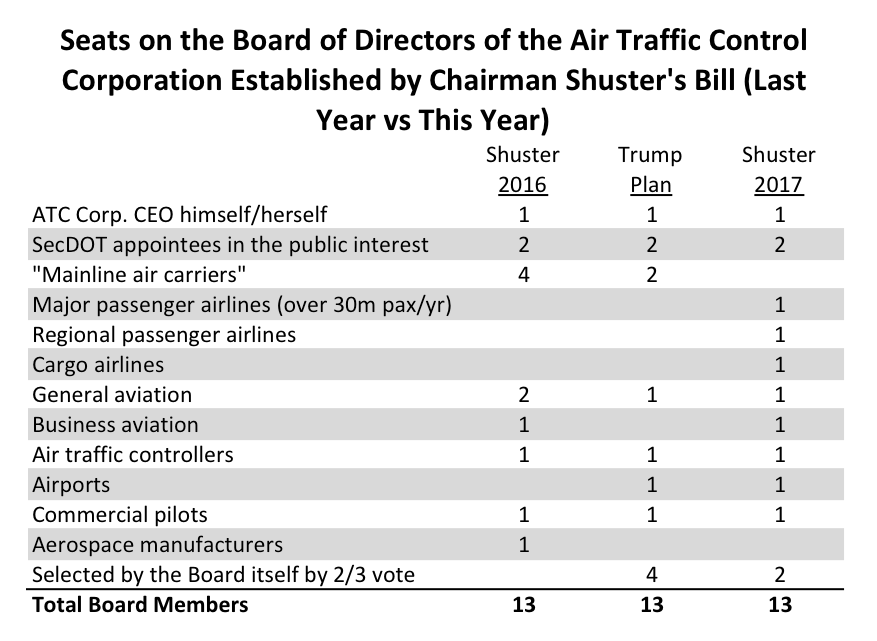

Regarding the board structure, this most recent bill proposes a 13-member board where a number of stakeholders nominate people to the board. The table below shows the proposed board composition, and compares it to last year’s Shuster bill as well as the Administration principles for ATC reform, released in June.

In the current bill, airlines get three seats out of 13 (23 percent of the seats). One of those seats goes to major passenger airlines, the other to cargo airlines, and the other to regional airlines (excluding those owned by larger carriers). In last year’s proposal major passenger airlines got four seats to themselves (31 percent). Seven seats are distributed to a wide range of stakeholders: the government (the only ones that nominate more than one director), general aviation, business aviation, air traffic controllers, airports, and pilots. Then, those 10 people select another two directors plus the CEO of the company. These directors will serve four-year terms, up to a total of eight years.

But, what stops those directors in acting to the benefit of the organizations that nominate them instead of the benefit of the ATC system? Two reasons. First, the structure of the board itself, where no stakeholder has a majority. This forces the board to reach compromises amongst disparate groups in order to get anything approved—the Canadians called this their version of “checks and balances”. Second, section 90307 outlines the fiduciary duties of the directors, along with general requirements to be able to be on the board.

Section 90307 makes it clear from the start that “The fiduciary duties of a Director shall be solely and exclusively to the Corporation”. What this means is that a director has to serve in the best interest of the corporation, not any other (for example their personal interest, or the interest of the stakeholder that nominates them). Ultimately, a director can be sued if this fiduciary duty is breached. The bill also outlines a number of other requirements:

- The directors have to be U.S. citizens;

- Cannot work for the ATC corporation (this does not apply, naturally, to the CEO);

- Is an elected official of any level of government, from Congress to state, local, or tribal (and after leaving Congress can only be nominated after two years; no restriction for other levels of government);

- Is an officer or employee of any level of government;

- Is a director, officer, trustee, agent, or employee of any of the stakeholders that nominate people to the board, or a “supplier, client, or user of the Corporation’s services”.

In summary, no elected officials nor government employees, and the organizations that nominate people cannot nominate people that are currently associated with them.

This is the proposed law, but how will this translate in the real world? Luckily, we have just the right example north of the board: NAV CANADA, the Canadian nonprofit system created in 1996, from which the Shuster bill got much of its inspiration. In Canada, the board of directors is composed of 15 people, nominated by four different groups:

- Four directors are nominated by the National Airlines Council of Canada, representing commercial airlines;

- Three directors are nominated by the Canadian government;

- Two directors are nominated by the NAV CANADA Bargaining Agents Association, representing the employee unions;

- One director is nominated by the Canadian Business Aviation Association, representing business and general aviation;

- Four independent directors, nominated by the board itself;

- The CEO.

Like what is proposed in the AIRR Act, these board members cannot work for any company associated with the group that nominates them, and they have a fiduciary duty to NAV CANADA. But what kind of people ends up serving in this board? Let’s take a closer look at the current board:

- The airlines nominated three former airline CEOs and a former airline vice-president;

- The government nominated high level executives with experience in banking and telecommunications;

- The unions nominated a lawyer and an union executive (from a nurses’ union, not one related to NAV CANADA);

- General and business aviation nominated a former consultant of their association;

- The four independent members are executives (former and current) coming from a university, a stock exchange, an energy company, and Canada Post (the mail company);

- The CEO, Neil Wilson, is a lawyer who started at NAV CANADA in 2002.

In summary, the organizations represented on the board in general nominate people that used to be associated with them, and the government and the board itself nominates high level executives, some of them retired, some not. In the U.S., if ATC is ever spun off, it is expected that we end up with a similar situation, where the stakeholders nominate people previously associated with them, and the remaining board members come from a variety of industries.

For more on the issue of ATC reform see our February report Time for Reform: Delivering Modern Air Traffic Control, as well as our FAA Reform Reference Page, which includes everything related to ATC reform (and aviation legislation in general). Our analysis of the Shuster bill is here and here.