May 19, 2017

On May 8, Georgia Governor Nathan Deal signed a law that explicitly allows for the operation of self-driving vehicles with and without human drivers. This marks a significant change of heart for a state that merely two years ago was squeamish about enacting policies around automated vehicles (AVs), fearing that the technology was not sufficiently mature to be regulated.

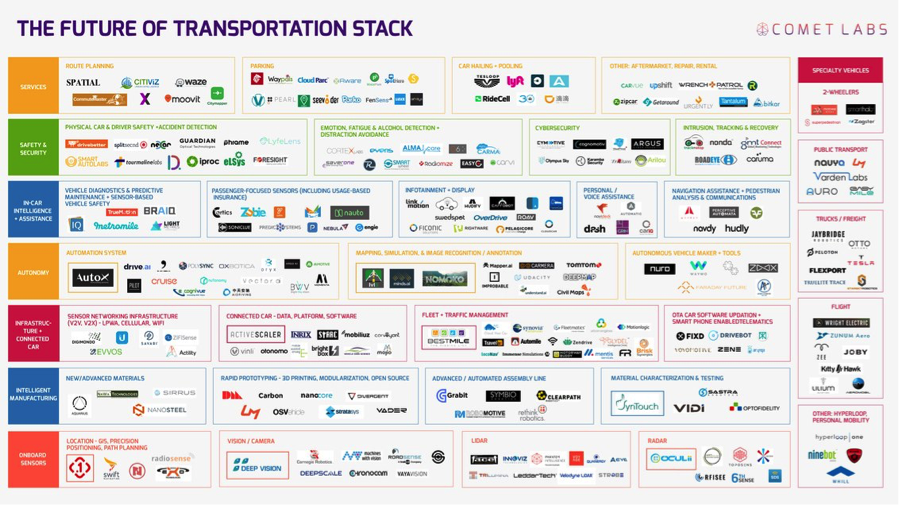

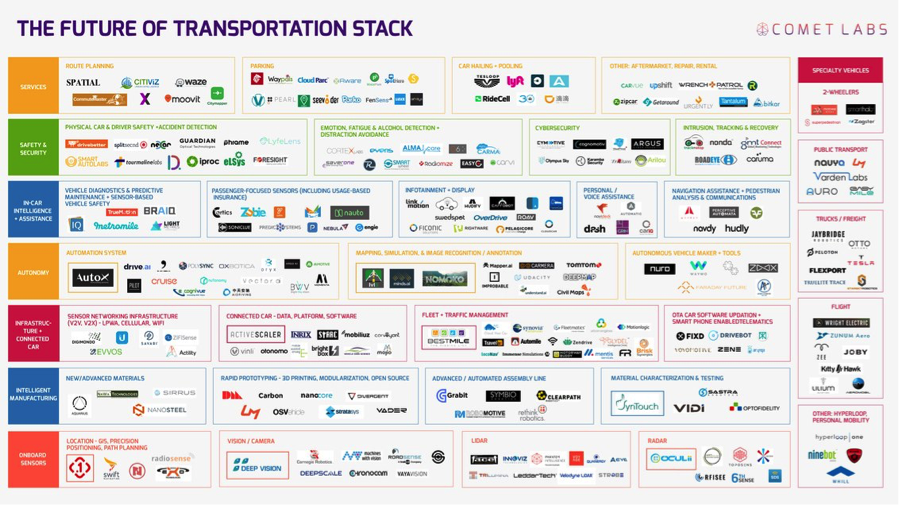

AV technology is advancing rapidly, and development has only accelerated in recent years, thanks to 263 companies working on the hardware and software components to support them.

(Courtesy of Comet Labs, via Wired)

This flood of private sector investment and the flurry of media attention around AVs have drawn the attention of officials at all levels of government. This is most pronounced among state legislatures who, in the absence of federal regulations on AVs to preempt them, are considering and enacting myriad policies to attract AV developers to their states.

But as more states pass AV laws, there is rising concern that AV developers face regulatory uncertainty caused by a patchwork of disparate state legislation – which, in a worst-case scenario, would require companies to understand and comply with 50 different regulatory structures in order to operate AVs in every state.

The enactment of SB 219 makes Georgia the fourteenth state, plus the District of Columbia, to pass a law around the testing, operation, and/or commercial deployment of AVs. Like many other state laws passed in recent years, the language of SB 219 closely resembles that of Nevada and California – two of the first states to pass AV legislation in 2011 and 2012, respectively.

And yet, the law differs from most others in the one area that matters most – the definition of an automated vehicle. As ETW has written previously, inconsistent definitions for AVs have proliferated federal and state policies and discussions, generating significant confusion among policymakers, industry, and the general public.

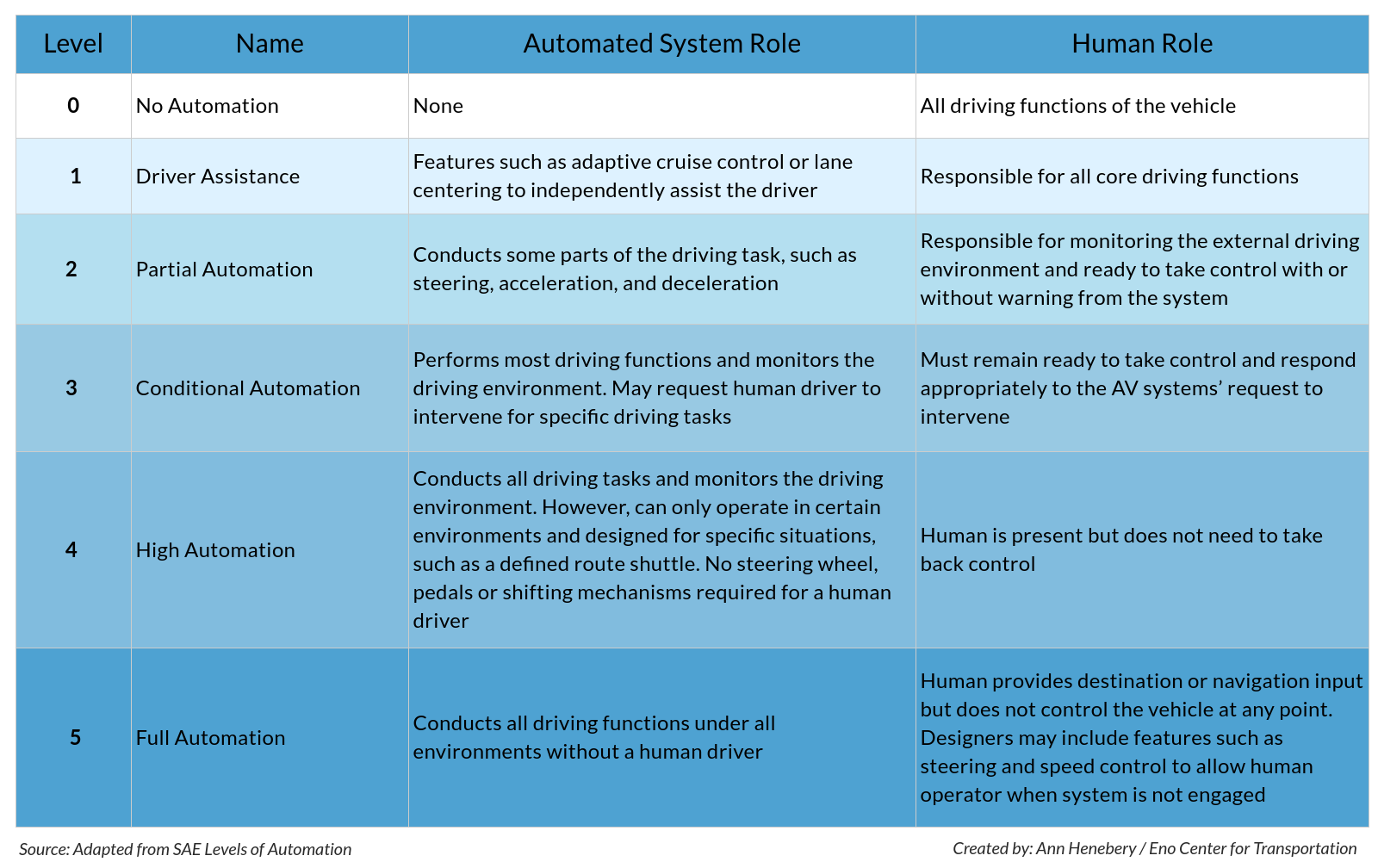

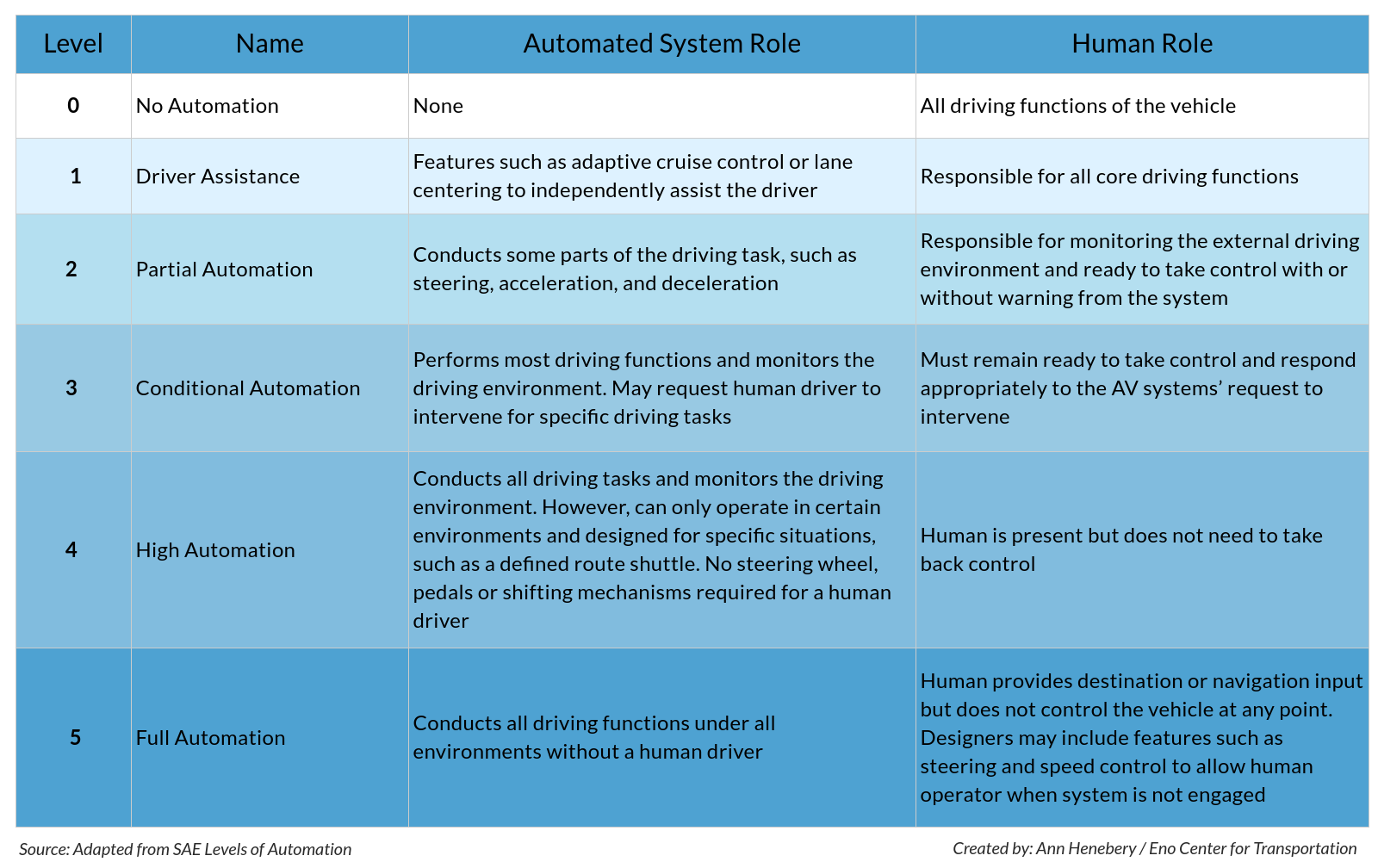

In a recent report, the Eno Center for Transportation recommended that policymakers should adopt the formal designations of the six levels of vehicle autonomy, as outlined by the Society of Automotive Engineers International (SAE) in SAE J3016: : Taxonomy and Definitions for Terms Related to Driving Automation Systems for On-Road Motor Vehicles. This industry-accepted standard provides clarity around the capabilities and limitations of AVs as automated driving functions are increasingly integrated into vehicles. An adapted version of this classification scale is displayed in the chart below.

These designations are also critical for consumer safety, as human drivers must know when they are expected to monitor the road and be prepared to take over the task of driving from an automated system.

Quite simply, Georgia’s new law defines fully autonomous vehicles in the state’s motor vehicle code as a vehicle that can drive itself without any human intervention, provided that it is operating in an environment in which it is designed to drive (also referred to as the operational design domain, or ODD).

While Georgia’s law uses some of the same terms as SAE to define automated functions, it falls short of providing sufficient clarity around AVs by defining fully autonomous vehicles (but not what SAE classification they fall under) and failing to acknowledge lower levels of vehicle automation.

However, this law does explicitly allow for the operation of AVs without human operators present in the vehicle (also known as driverless cars), making Georgia the third state to do so, following the lead of Florida and Tennessee.

In 2014, the Georgia House of Representatives formed the Autonomous Vehicle Technology Study Committee to research the state of AV development as well as the potential benefits and risks of passing laws to regulate them. The committee found that the ultimate impacts of incorporating AVs into the state’s transportation networks remained unknown, particularly with respect to the state’s existing torts system.

In its final report, the committee discouraged the state legislature from passing AV laws until the technology was sufficiently mature, stating: “To recommend any changes to our current system at this time would be putting the proverbial cart before the horse.”

They continued: “Too often we want to rush action to show we are committed to a concept. This committee has shown its interest in the further development of autonomous vehicles in Georgia, but we hold firm in the belief that at this time any new regulations, definitions, or changes to our system would shock the market and cause delay in this exciting technology.”