This week, the U.S. Government Accountability Office issued a new report entitled Commuter Rail: Information on Benefits and Funding Challenges for Service in Less Urbanized Communities. The report was requested by the Senate Appropriations Committee in September 2019, when their annual committee report asked GAO to report “on the cost of operating, including extending current service and adding additional frequency to, commuter rail transportation systems in small and rural communities.”

Obviously, between September 2019 and now, COVID-19 arrived and threw all of the financial models for commuter rail and the rest of mass transit out the window. GAO continued the study anyway, interviewing officials at ten of the nation’s 31 commuter rail authorities and analyzing the detailed NTD reporting data from all 31 commuter rail agencies.

The two paragraphs of the “Results in Brief” section of the report are somewhat predictable:

Stakeholders told us that commuter rail provides a number of economic and quality-of-life benefits, particularly for communities in less urbanized areas. For example, commuter rail agencies said that several large companies have chosen to locate along commuter rail corridors to draw on the regional labor market, including its less urbanized areas. Stakeholders also said that commuter rail could increase mobility and transportation options, as well as access to employment and essential services for individuals who live in the service area. At the same time, however, officials at commuter rail agencies with whom we spoke pointed to considerable infrastructure and operational costs making commuter rail more expensive to provide compared to some other transit modes. Supporting commuter rail in less urbanized communities may also pose additional funding challenges for these commuter rail agencies and local communities. For example, less populated areas may have difficulty raising the local match required to secure federal funding for a transit project.

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated existing funding challenges for commuter rail agencies. Systems have experienced significant declines in ridership and associated fare revenue, and in funding from state and local sales taxes. Commuter rail agencies reported to NTD that ridership declined an average of 79 percent from September 2019 to September 2020. In addition, some agencies told us that long-term shifts in commuting patterns and increased teleworking among former riders could affect commuter rail funding long after the immediate effects of the pandemic are over. For commuter rail agencies that rely largely on state and local funding, continued declines in tax revenues will become increasingly challenging the longer the pandemic lasts.

Some less predictable findings:

- Right-of-way costs. “officials at some commuter rail agencies we spoke with said right-of-way fees pose financial challenges. With respect to right-of-way fees, commuter rail agencies often operate some or all of their trains as “tenants” on the track of another railroad—such as Amtrak or a freight railroad—known as the “host.” The tenant may pay the host fees to access, dispatch, and maintain the track infrastructure, depending on the arrangement. For example, Metrolink in Southern California pays these types of fees to host freight railroads on 44 percent of its total route miles. Other transit modes do not need to pay to use their right-of-way; for instance, bus systems do not need to pay to drive on public roads. As such, it may be challenging for commuter rail agencies to alter their scheduled service in response to changes in ridership demand, in part due to restrictions in their agreements with other track users.”

- PTC costs. “Officials at three of the 10 commuter rail agencies we spoke with noted that installing and maintaining their PTC systems significantly adds to overall capital and operating costs, potentially affecting the ability to extend the service area. One commuter rail agency official said that, to install PTC by the federal deadline, the agency had delayed other work on the system. The agency estimates that its ongoing annual PTC maintenance costs will be approximately $3-to-$4 million dollars, which could be as high as 14 percent of its annual operating budget.”

- Post-COVID. “In the long term, commuter rail agencies may need to reassess their pre-pandemic service levels. For example, officials at seven of the 10 commuter rail agencies we spoke with said long-term shifts in commuting patterns, such as increased teleworking among former riders, could affect their service long after the immediate effects of the pandemic are over. Accordingly, it is unclear how the economic and quality-of-life benefits commuter rail service provides to riders may change if lower levels of ridership persist.”

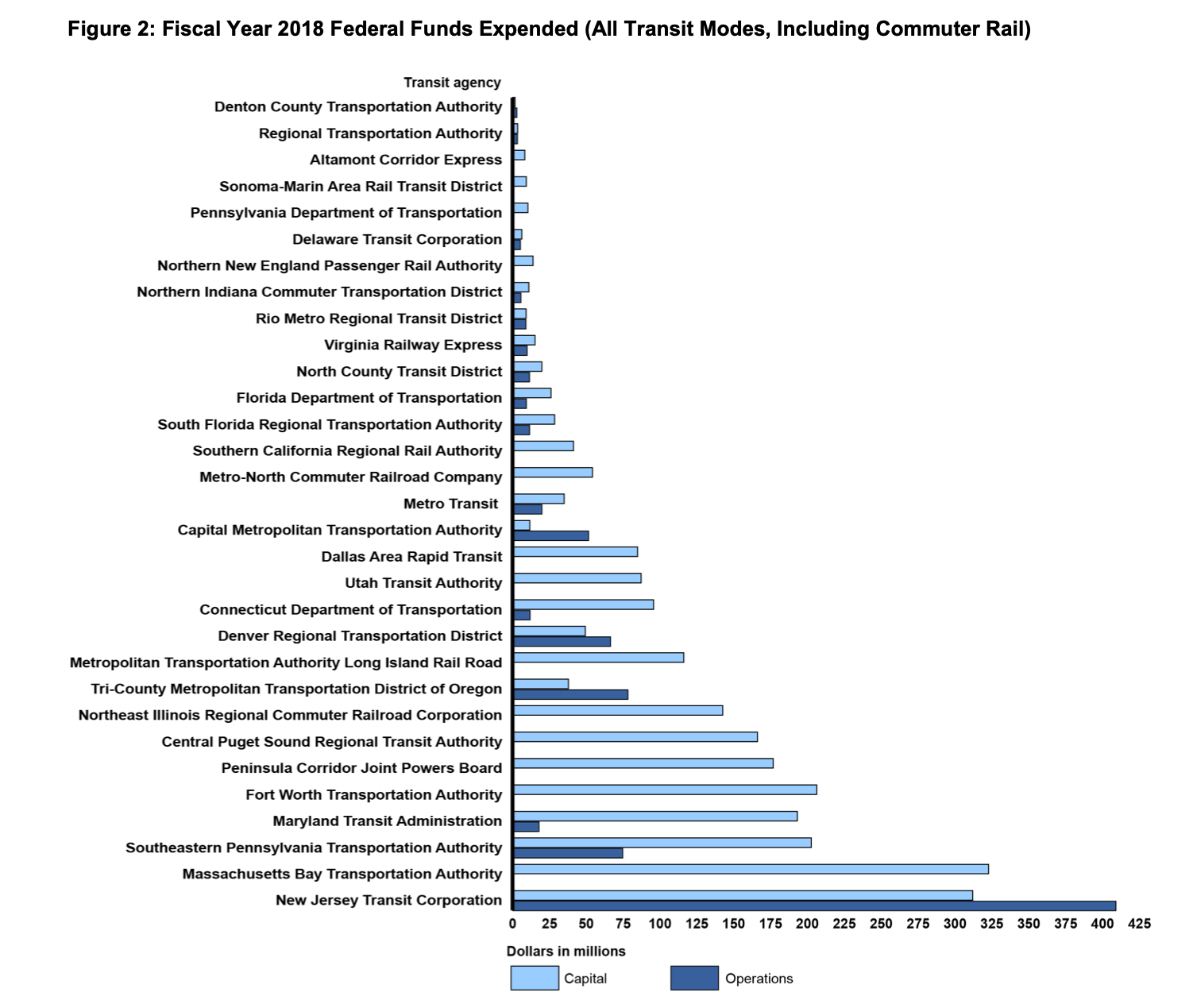

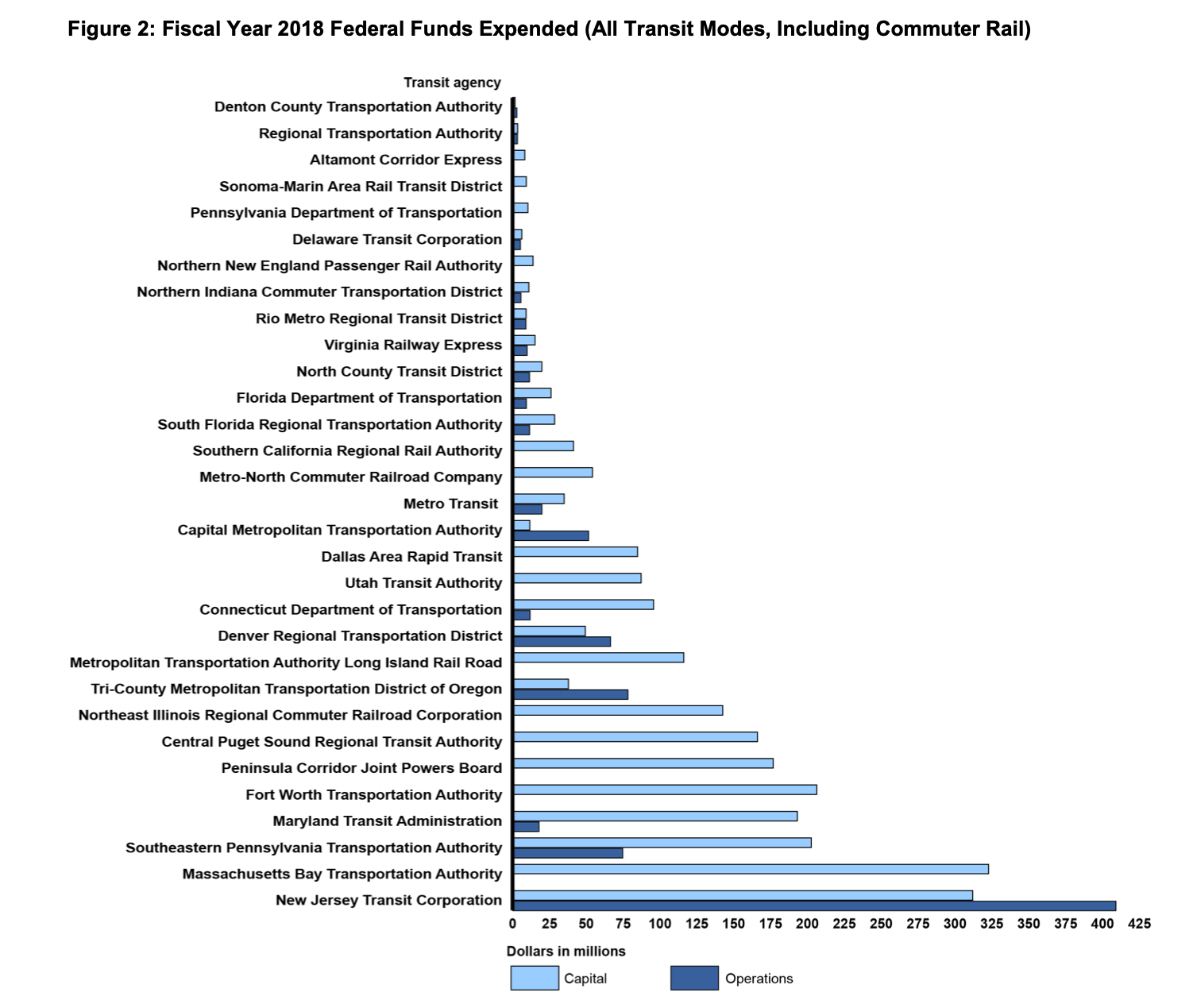

But the most valuable part of the report – and the reason, Dear Reader, you should bookmark it in your web browser – is because GAO has assembled a lot of data on those 31 commuter rail systems in the back of the report, including how much money each commuter rail system spent from each different federal program in 2018, and profiles of each commuter rail authority that include mileage and ridership stats and maps of the service area that show local population density, station locations, and the number of daily riders per station.

And charts like this one: