The FAA reauthorization law enacted on October 5, 2018 mandated, by our count, 119 new studies or reports to be submitted to Congress, many of which had unrealistic deadlines attached. The U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) this week began fulfilling its share of the reporting burden, with new reports on the Essential Air Service subsidy program and on airline oversales and denial-of-boarding practices.

EAS. The Essential Air Service program provides financial aid to airlines that serve small airports that would otherwise have no scheduled airline service at all because the routes are that unprofitable. There has always been some sort of government subsidy for these routes, going back to the dawn of aviation – originally the subsidies were paid by the Post Office to private air mail carriers (which later started carrying passengers as well as mail).

The subsidy program was transferred from the Post Office to the Civil Aeronautics Board in the 1950s. But the CAB forced indirect subsidies as well – they would require an airline to service an unprofitable route but also give them a lucrative route between larger cities, so the passengers on the big city-pair were, in effect, subsidizing the service to the unprofitable city.

The Airline Deregulation Act of 1978 ended route cross-subsidization, but out of concern for the disruption to the system, the direct subsidies to carriers were maintained as a transitional Essential Air Service subsidy program. EAS was supposed to sunset in 1988 but Congress extended it and, in 1996, made it permanent.

The program has long been a target of free-market Republicans in Congress who object to any operating subsidies in general but who also loved to lampoon the excesses of the EAS program. Back in 2000, Congress passed a law restricting EAS per-passenger subsidies to $200 per passenger per flight unless the airport receiving service was more than 210 miles from the largest medium or large hub.

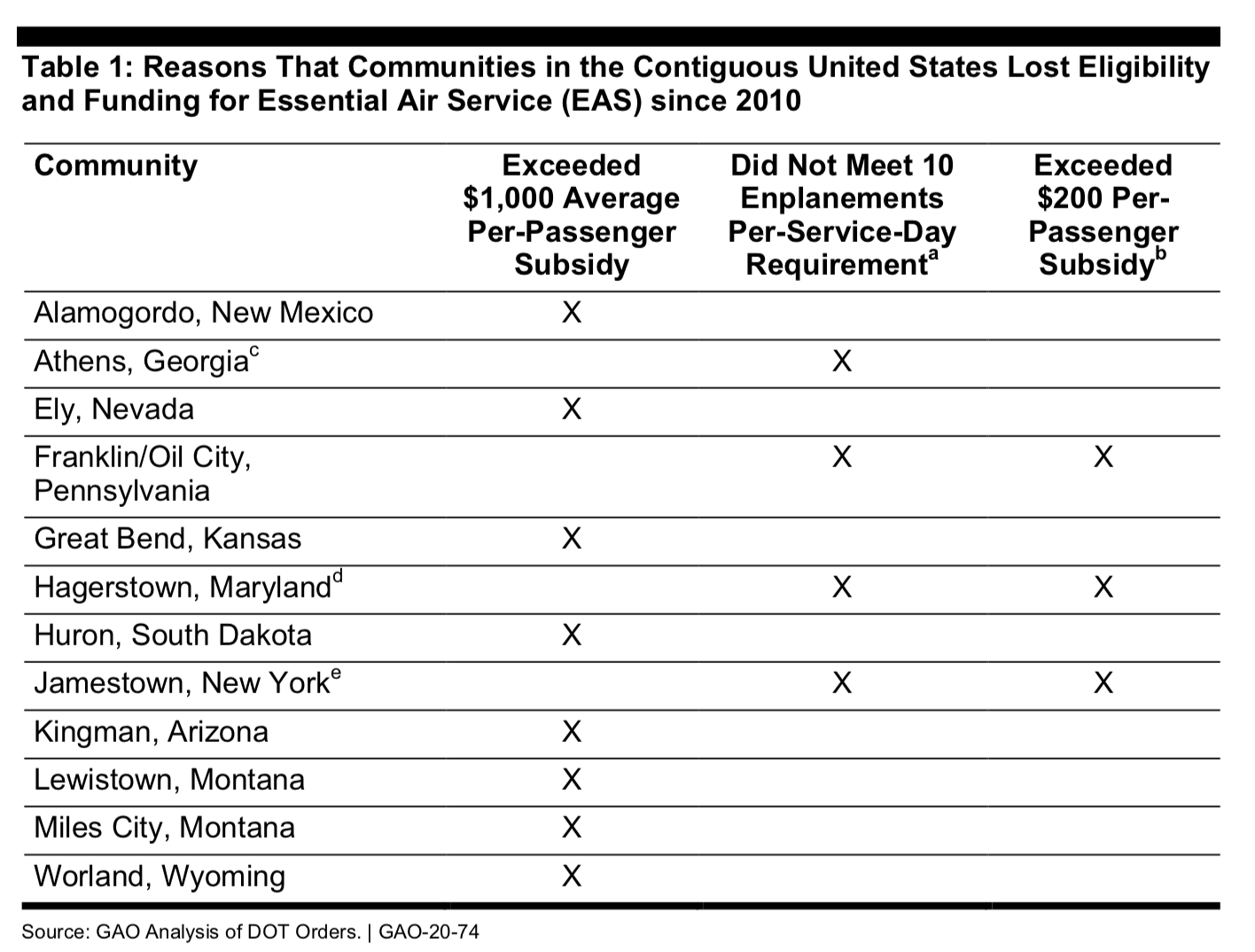

In 2011, Congress was able to enact a law capping EAS subsidies at $1,000 per passenger per flight even for the remotest airports. A minimum number of daily enplanements (10 passengers per airport per day) and a limitation on program eligibility to airports that have been receiving EAS aid since 2010 were added in 2012.

Section 452 of last year’s FAA law required GAO to study the effect those changes have had on the EAS program and to report back to Congress within 180 days of enactment. The report, issued 432 days after enactment, is entitled Commercial Aviation: Effects of Changes to the Essential Air Service Program, and Stakeholders Views on Benefits, Challenges, and Potential Reforms.

Key findings of the report include:

- “the overall number of communities receiving EAS remained about the same; however, EAS expenditures increased from $161 million in fiscal year 2010 to $277 million in fiscal year 2018…DOT officials said this increase was due, in part, to factors affecting the entire airline industry, such as increased labor wages.”

- “pilot wages have increased, making it difficult to provide quality service without exceeding the subsidy caps.”

- “the $200 subsidy cap has not changed for several years to account for inflation or these increased costs. To address these and other challenges, stakeholders suggested a number of options, such as indexing the $200 subsidy cap to inflation or allowing communities that lost eligibility to re- apply for the program.” (The report notes that, had the $200 cap been indexed for inflation, it would be $283 today, and 10 more airports would be under the cap instead of over it.)

- “A decline in the number of enplanements may also lead to a reduction in AIP funding available to the airport. AIP funding is important for small communities that have fewer financial resources than large- or medium-sized airports. AIP funding can help airports make improvements that could attract more business, such as from commercial and business aviation.”

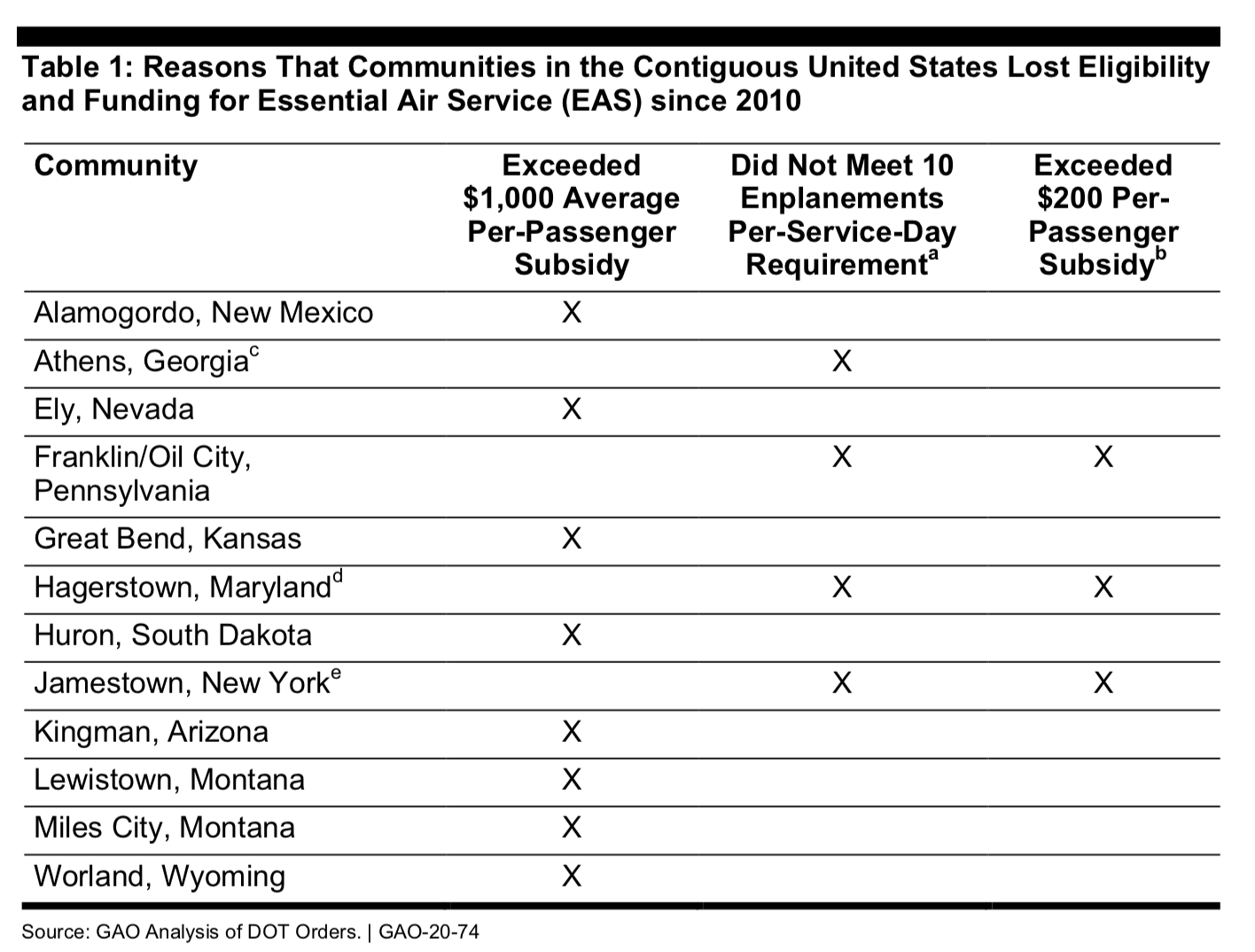

The study found that the legislative changes to the program in 2010 and thereafter have only caused 12 cities to lose airline service:

However, the report notes that “many communities that did not meet eligibility requirements since 2014 continue to receive EAS because they were granted at least one waiver from DOT. From fiscal year 2014 through fiscal year 2019, DOT granted a total of 110 waivers to 37 communities—about one-third of the number of communities currently in the program…The number of communities that received waivers in recent years has increased during this time period, in part due to DOT’s decision to enforce the $200 subsidy-per-passenger cap. DOT granted waivers to 15 communities because they experienced a hiatus in service during the year that resulted in the community’s not meeting the 10 average daily enplanements requirement or exceeding the $200 subsidy-per-passenger cap.” (That chart is too large to reproduce here but is found on page 18 of the report.)

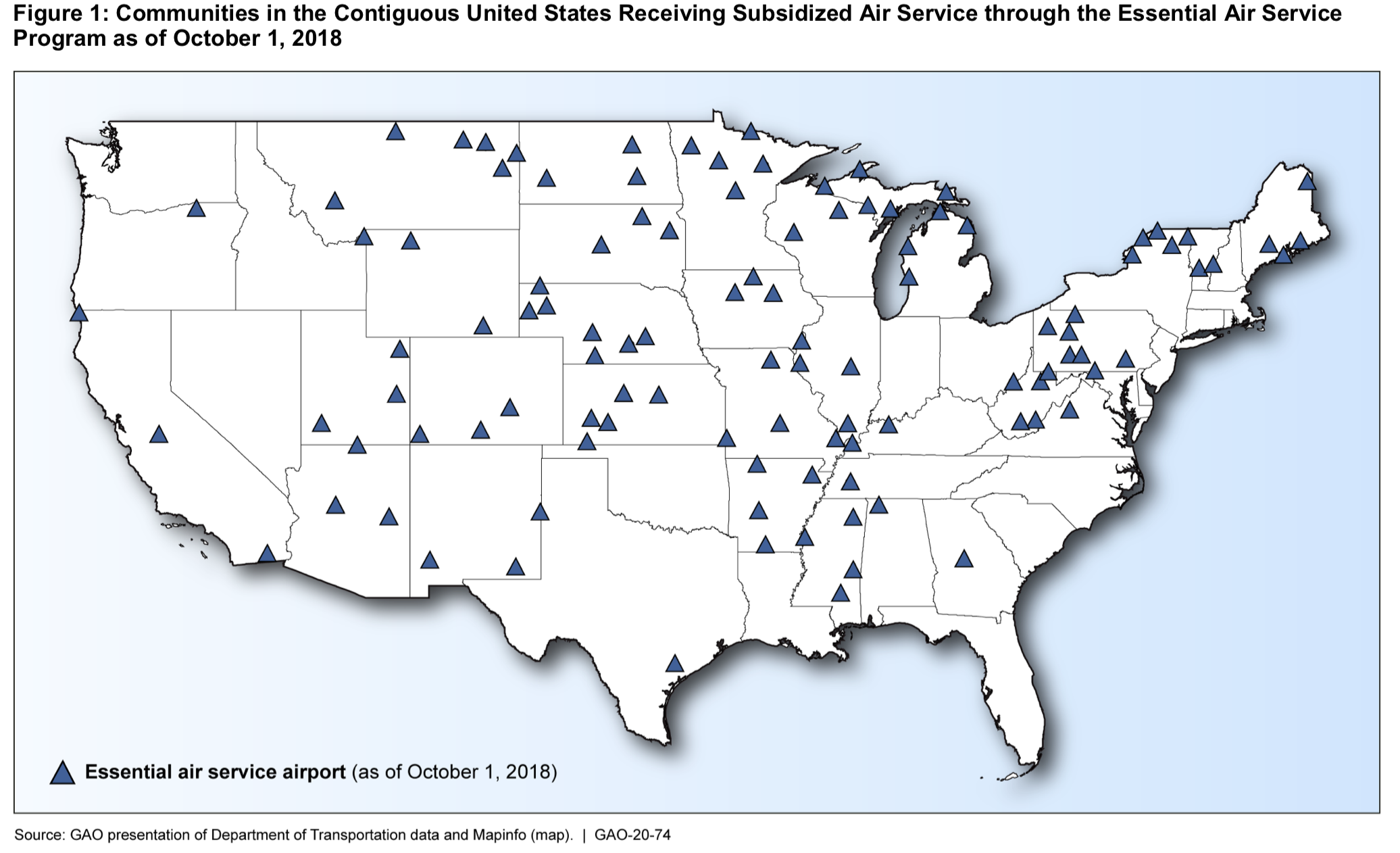

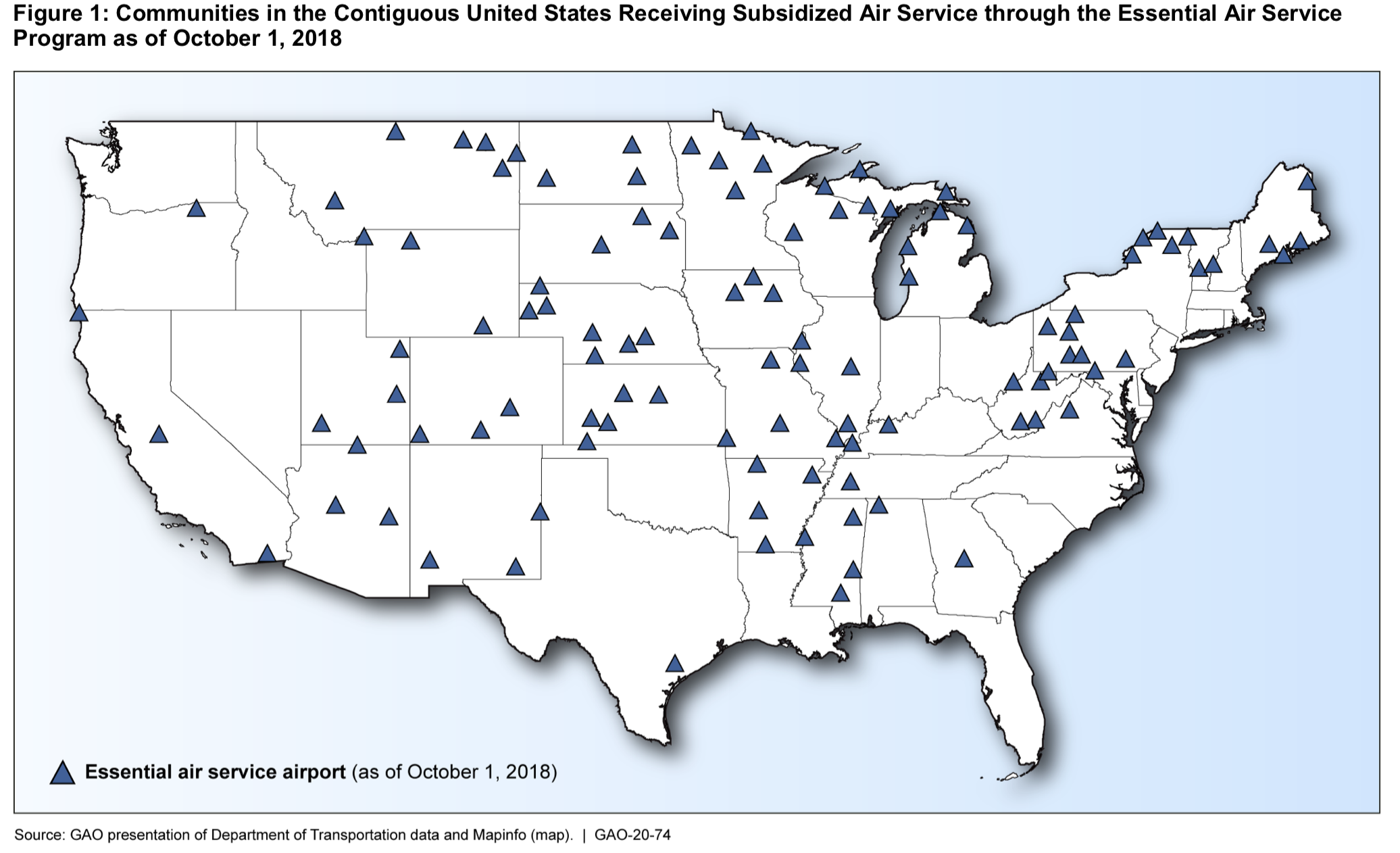

One look at the map of airports currently receiving EAS subsidies makes it clear why the U.S. Senate will never, ever allow the program to die:

Oversales. A lot of the reports and mandates from Congress to federal agencies are “ripped from the headlines.” In this case, the April 2017 incident where a 69-year-old man who had bought a ticket and been seated on his United Express flight was knocked unconscious (concussion, broken nose and two front teeth knocked out) and dragged off the plane prompted section 425 of the 2018 Act, the “TICKETS Act.” (It was based on a Senate bill introduced immediately after the incident.)

That section not only made it illegal for airlines to deny revenue passengers their seats against their will once they have checked in before the deadline and had their boarding pass scanned by the ticket agent – that section also required a GAO report on “airline policies and practices related to oversales of flights.” (As it turns out, the United Express flight that prompted the TICKETS Act was not oversold – the airline was bumping passengers to make room for a flight crew that had to get to another city because the flight on which they were booked was delayed.)

The new GAO report, Airline Consumer Protections: Information on Airlines’ Denied Boarding Practices (due on October 5, 2019, dated December 10, 2019) analyzes both “voluntary denied boardings” (where passengers volunteer to give up their seats in exchange for cash or flight vouchers) and “involuntary denied boardings” which are exactly what they sound like.

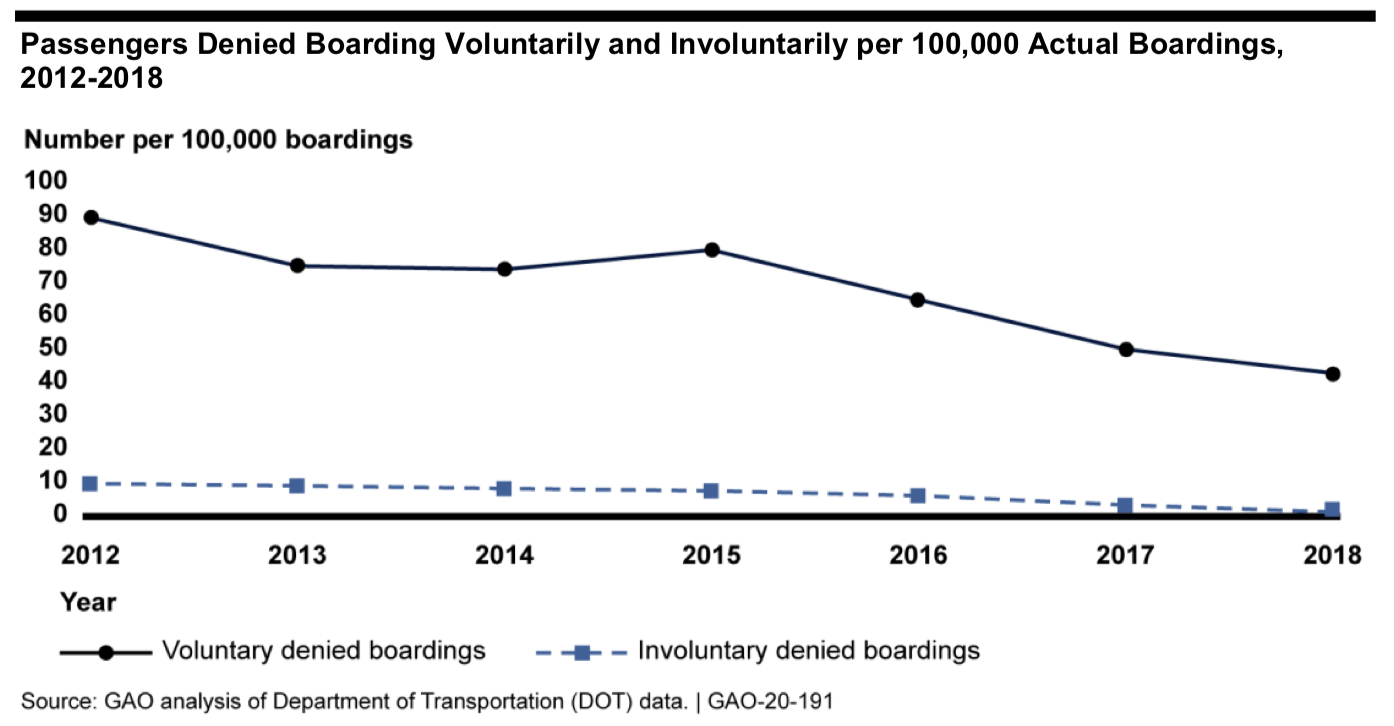

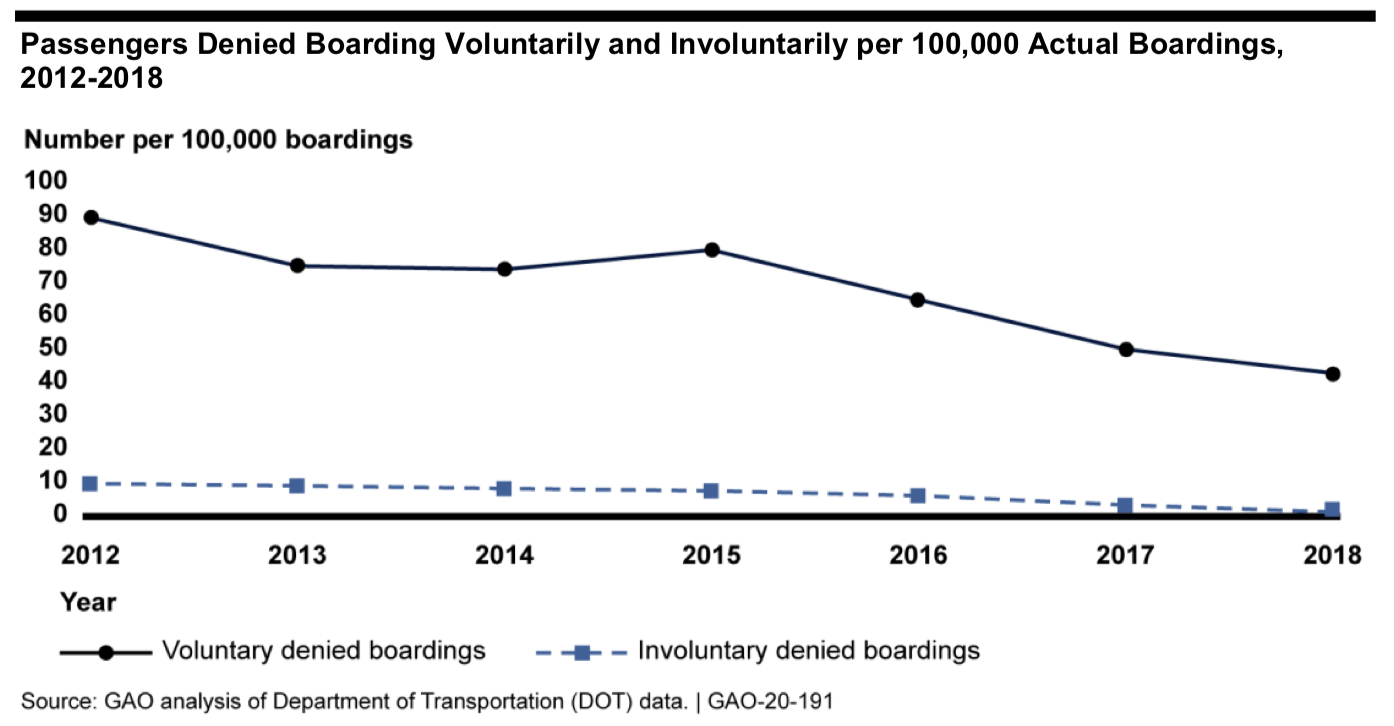

The former are far more numerous than the latter – per the study, in 2018, about 43 passengers per 100,000 actual boardings took the money or voucher in exchange for being bumped, but only 1 passenger was involuntarily denied boarding.

Furthermore, per the study, airlines have been doing a good job over the last six years of reducing the number of denied boardings – in 2012, there was about one denied boarding per 1,000 actual boardings, whereas in 2018 (as noted above) it was 4.4 denied per 10,000 actual boardings.

Put another way (in the report): “in 2012, for every one passenger denied boarding involuntarily, about nine volunteered to be denied boarding. In contrast, in 2018, for every one passenger denied boarding involuntarily, about 33 volunteered to be denied boarding.”

DOT already requires minimum levels of compensation for involuntary denied boarding passengers (found in 14 CFR 250.5) – the TICKETS Act also ordered DOT to update that regulation to make it explicit that those are minimums, not maximums, but that regulatory update has not been promulgated yet).

The report makes clear that not everyone who is denied boarding involuntarily is due compensation: “in certain situations, passengers who are denied boarding involuntarily may not be eligible for compensation. For example, airlines are not required to compensate passengers if an airline uses a smaller aircraft than originally planned for operational or safety reasons and thus cannot accommodate all confirmed passengers. Our review found that the percentage of passengers that were involuntarily denied boarding who qualified for 35 compensation decreased from 76 percent in 2012 to 64 percent in 2018.”

Another key finding of the report is that airlines have actually reduced their overbooking: “Some airlines have reduced their rate of overbooking or eliminated them altogether in an effort to reduce voluntary and involuntary denied boardings, according to stakeholders and our prior work. In our 2018 report, representatives from three airlines told us their airline had reduced or stopped overbooking flights. Our review of seven airlines’ customer service documents found that two airlines explicitly stated that they do not overbook their flights.”

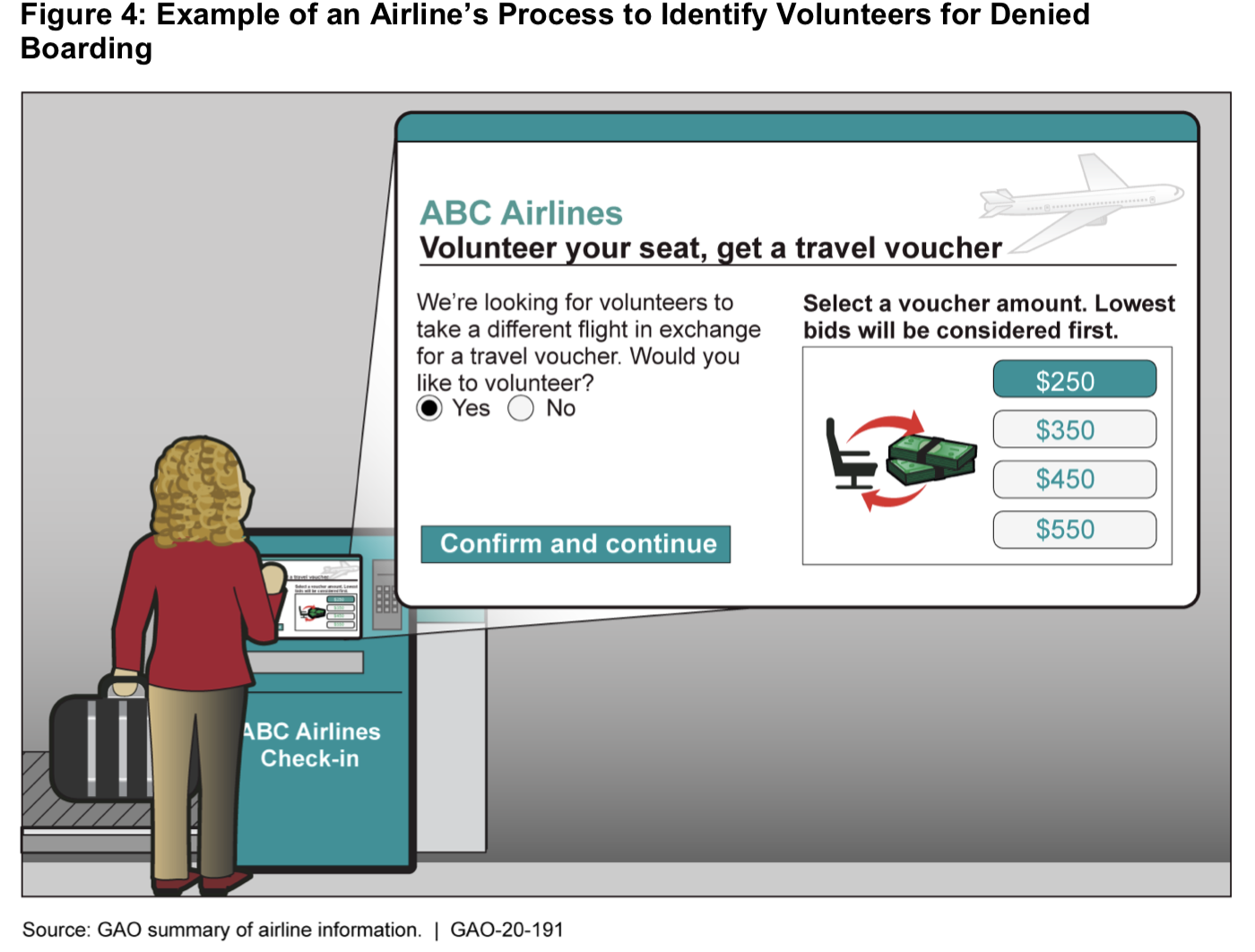

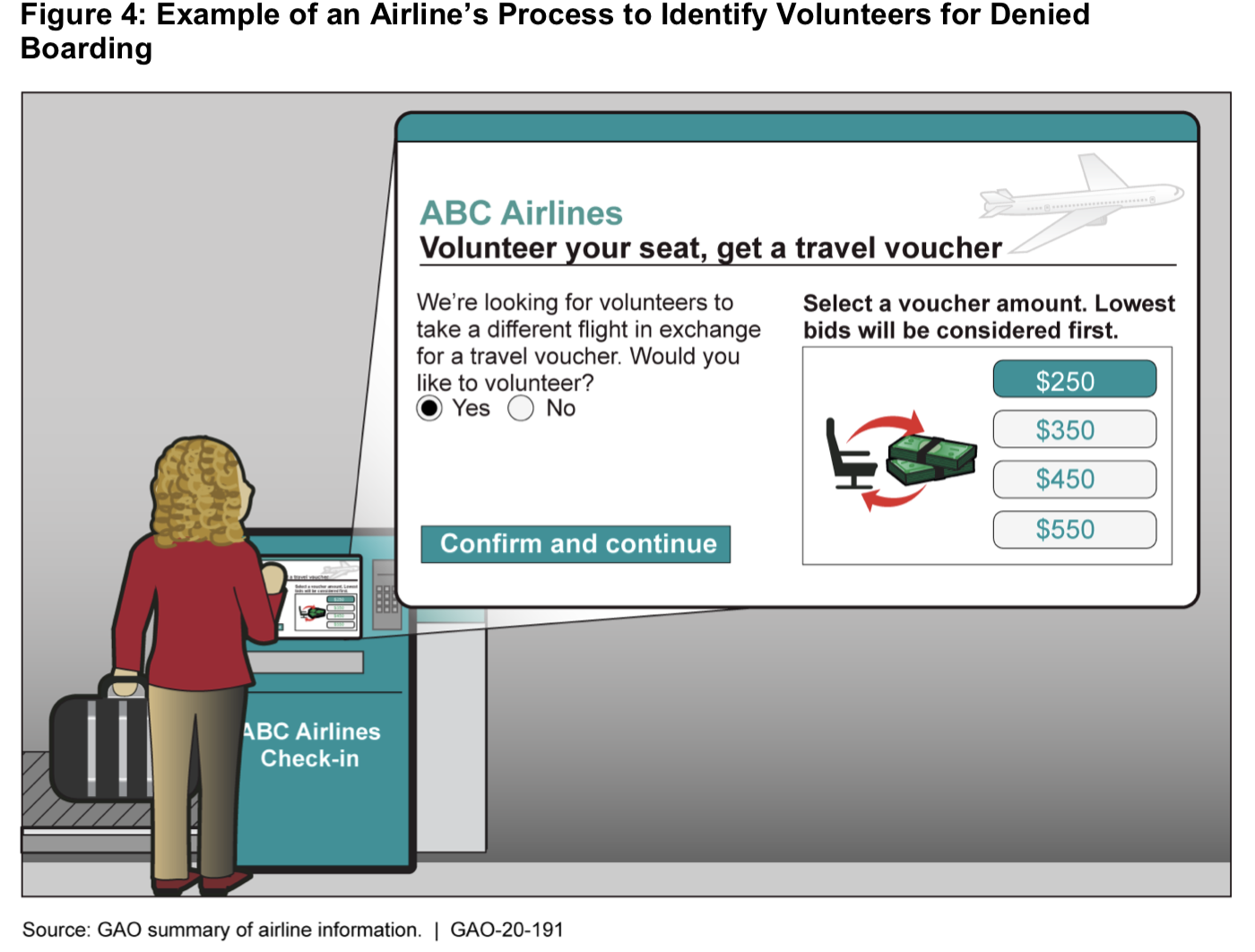

Another innovation is that airlines have increased and diversified the compensation they offer passengers in exchange for denied boarding (Amazon gift cards! Free iPads!) and some airlines conduct a kind of auction amongst passengers to see which ones are willing to give up their seats for the lowest amount of money (charming GAO infographic included below because it was too good not to use).