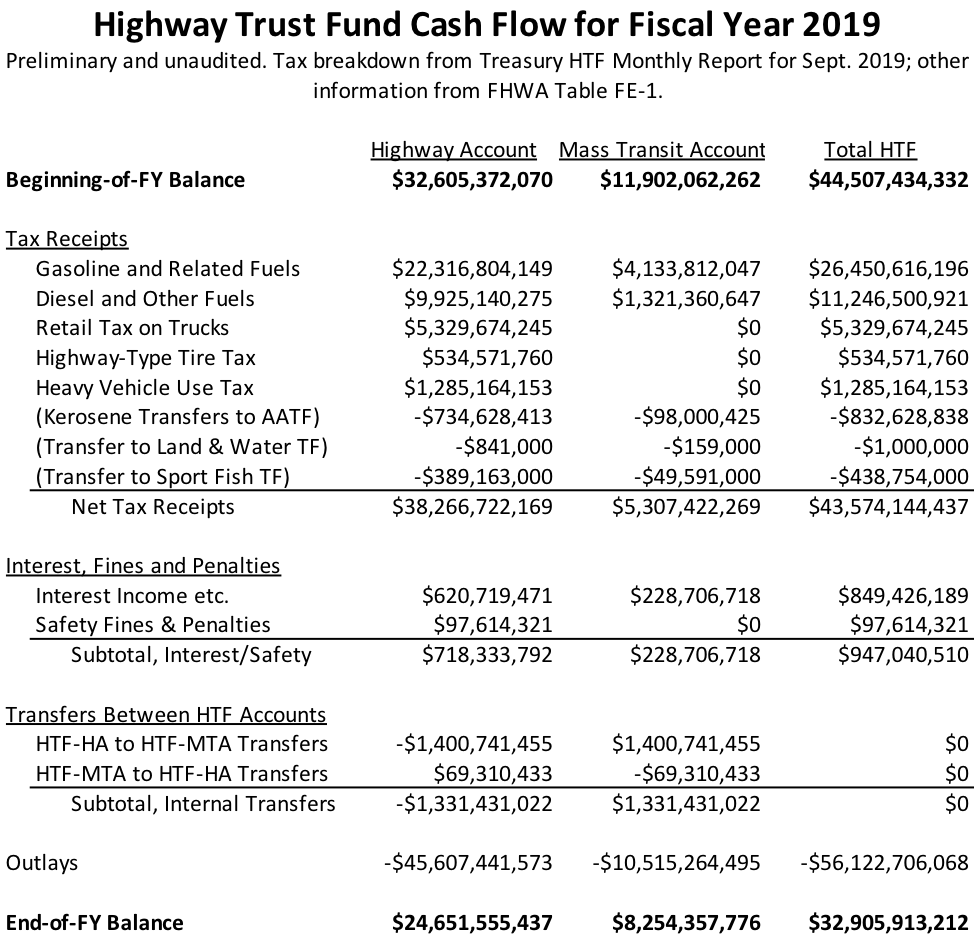

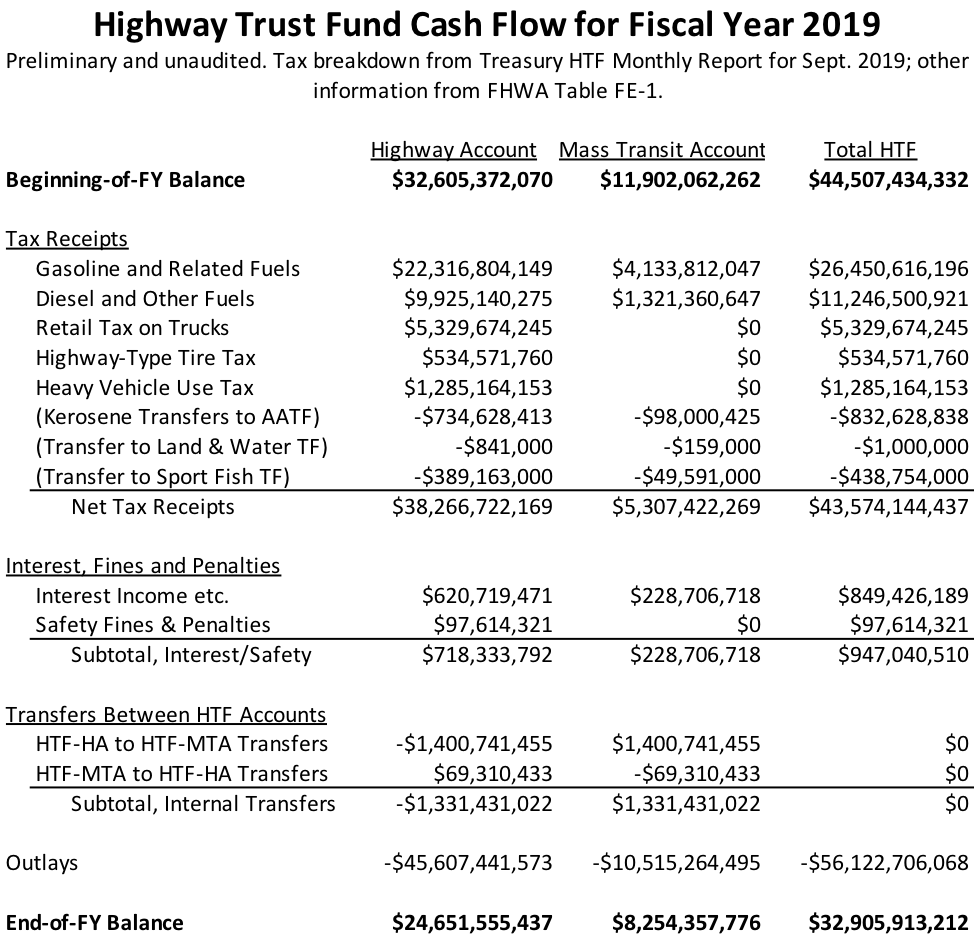

The Highway Trust Fund ran a “real” cash deficit of $12.45 billion in fiscal year 2019, which was slightly less than the $12.63 billion deficit it ran in fiscal year 2018. However, this was entirely due to receipts from the three taxes that fall exclusively on the trucking industry being up $1.4 billion from last year. HTF outlays were $884 million higher than last year, while receipts from gasoline, highway diesel fuel, and other motor fuels were stagnant.

Totals are shown below.

The Federal Highway Administration released the final 2019 update of Table FE-1 this week, which included spending and transfer data. (Tax data came out last week in the monthly Treasury report on the HTF for September 2019.)

When we say “real” cash deficit, we intend to exclude bailout money deposited in the Trust Fund on an ad hoc basis since the Trust Fund ran out of money in September 2008. In addition, the process by which the federal government pays money to itself just because it issued interest-bearing bonds to itself has always struck us as silly. But due to the fact that, since September 2008, any balances held by the Highway Trust Fund have been entirely due to the $144 billion in bailout transfers, the federal government paying interest to itself for the privilege of holding money that it basically printed and gave to itself seems extra, super-duper silly. So our “real” deficit calculations exclude bailout transfers and interest.

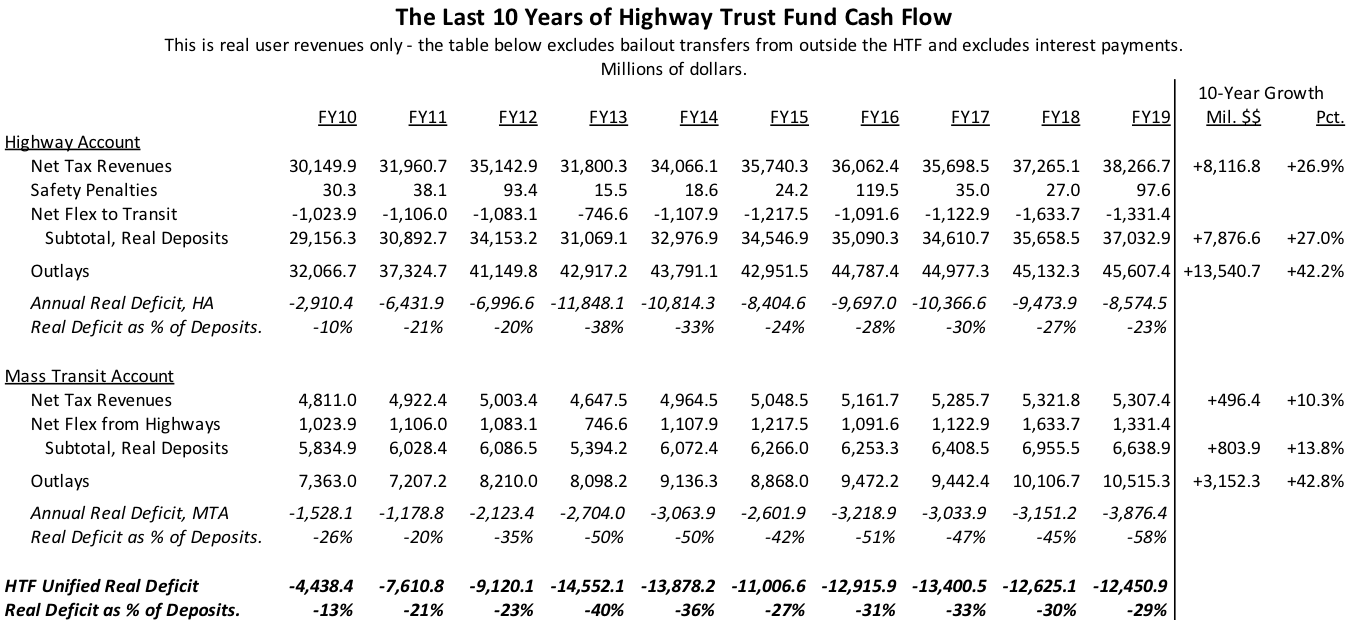

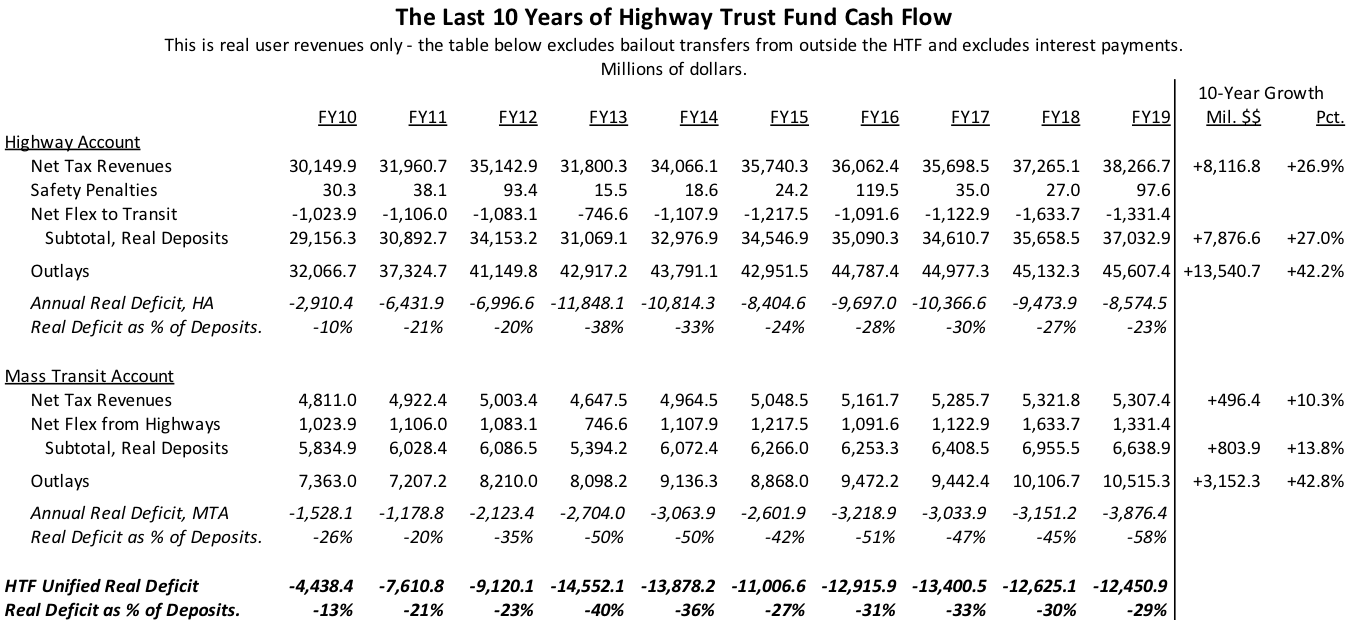

Over the last decade, the real Trust Fund deficit has risen from $4.4 billion in 2010 and peaked at $13.4 billion in 2017 before surges in truck tax revenue in 2018 and 2019 cut that deficit slightly. But the truck and trailer sales tax, the truck tire tax, and the heavy truck use tax are only deposited in the Highway Account – they are not split with Mass Transit Account. As a result, over the last decade, receipts from motor fuel taxes (which are split between the two accounts, 84.4%-15.6% for gasoline and 88.2%-11.8% for diesel), have only increased by 10.3 percent (most of that growth due to diesel, which is primarily, but not exclusively, used by commercial trucks). But Highway Account tax revenues in 2019 were 26.9 percent higher than they were in 2010 because the rate of growth of trucking tax receipts was so much higher than the rate of growth of fuel taxes.

(This cuts both ways. The next downturn in the business cycle will see trucking companies postponing the purchase of new trucks and trailers, and the truck taxes will drop by a much more precipitous percentage than will fuel use.)

But even though the Mass Transit Account’s dedicated tax base has only grown by 10.3 percent over the last decade, its spending has grown by about the same percentage as has Highway Account spending (FY19 MTA outlays were 42.8 percent above FY10, while FY19 HA outlays were 42.2 percent higher than FY10).

After you account for “flex” transfers (see below), which you have to do to not make transit outlays appear even more unbalanced than they already are, the real Highway Account deficit went from $2.9 billion in 2010, which was 10 percent of that year’s real deposits, to $8.6 billion in 2019, which was 23 percent of real deposits. But transit spending is much more out of balance, versus its dedicated revenues, than highway spending. In 2010, the Transit Account real deficit was $1.5 billion, which was 28 percent of that year’s deposits, and that has now grown to a real deficit of $3.9 billion, which is an astounding 58 percent of its real deposits.

Put another way, in 2019, for every real dollar deposited in the Highway Account (net), there were $1.23 in checks and electronic transfers drawn on the Account. But the Mass Transit Account wrote $1.58 in checks and transfers for every real dollar deposited in the Account.

Versus CBO projections. Because trucking excise tax receipts surged, and because the Mass Transit Account doesn’t get any of those trucking tax receipts, the final year-end balances in the HTF accounts diverge from the May 2019 Congressional Budget Office projections in different directions. The year-end Highway Account balance was $1.1 billion higher than CBO projected, which moves the eventual default date for that account a few weeks further away, but the Mass Transit Account finished the year $439 million worse off than CBO projected, and since the Transit Account will probably run out of money before the Highway Account, this means that the next CBO projection will probably accelerate the date of the next required Highway Trust Fund bailout by a bit.

|

May 2019 |

Oct. 2019 |

|

|

CBO Estimate |

Actual |

Difference |

| Highway Account |

23.542 |

24.651 |

+1.109 |

| Mass Transit Account |

8.693 |

8.254 |

-0.439 |

“Flex” transfers. States and metropolitan planning organizations have statutory authority, under 23 U.S.C. §104(f) and 49 U.S.C. §5334(i), to spend some of their apportioned highway contract authority on mass transit, or to spend some of their mass transit money on highway projects. The highway-to-transit transfers are always much larger than the transit-to-highway transfers, but no one can predict precisely how much the total transfers will be in each year because it is dependent on a lot of state and local decisions made during the year.

When a state transfers highway money to a transit project, or vice versa, contract authority and obligation limitation are transferred from the Federal Highway Administration to the Federal Transit Administration (or vice versa), but also, an equivalent amount of cash is transferred from one Trust Fund account to the other.

The Congressional Budget Office and the Office of Management and Budget each use placeholder estimates for the flex transfers in their funding projections, but they use different placeholders – CBO uses $1.0 billion per year, and OMB uses $1.3 billion per year. As the ten-year table above shows, the CBO estimate was much closer to accurate over the FY 2010-2017 timeframe ($1.06 billion, on average), but the net total highway-to-transit flex ballooned to $1.63 billion in 2018, and then dropped a bit, down to $1.33 billion in 2019, indicating that the OMB estimate has become the more accurate one lately.