December 22, 2017

This week’s fatal Amtrak derailment in Washington State between Tacoma and Olympia, killing three people and injuring scores of others, could not have been more high-profile. The very first train in revenue service on a new route jumped the track and crashed into the middle of the four southbound lanes of Interstate 5 at the start of morning rush hour. From the moment the first aerial view of the crash site from a news helicopter was broadcast, showing how far the lead engine had traveled from the track, it was clear to experts that the most likely cause of the derailment was overspeed (going too fast) into a curve.

The whole point of the new “Point Defiance Bypass” was to provide a much straighter route than the old, coast-hugging, windy route between that was shared with a lot of BNSF freight trains – the new bypass would allow fairly consistent speeds of 79 miles per hour along large stretches of the track. But federal investigators soon announced that the train had not slowed down from its circa-80-mph straightaway speed before heading into the curve to take the bridge over I-5, which had a much slower speed limit of 30 mph. While the investigation is only in the initial stages, overspeed is considered the likely cause as of this writing.

This quickly brought the issue of positive train control (PTC), a technology that automatically activates the brakes of trains to meet speed limits or red lights, to the forefront of debate once again. Sound Transit (the local mass transit agency which owns the track along the new bypass) had not yet completed installation of the PTC technology along the route, in conjunction with BNSF, which owns the rest of the track on which the Cascades trains operate and which handles train dispatching on the new bypass as well). Some combination of the Washington State DOT (which owned the locomotive and trainset) and Amtrak (which operates the train) made the decision to start the service along the new bypass a few months before the PTC was ready.

Background. In September 2008, in Chatsworth, California, a Metrolink commuter train hit a Union Pacific freight train head-on, killing 25 people. The National Transportation Safety Board investigation determined that the Metrolink engineer had been distracted by texting on his phone and missed the red light that showed that the UP train had the right of way, but the NTSB report also said that, “Contributing to the accident was the lack of a positive train control system that would have stopped the Metrolink train short of the red signal and thus prevented the collision.”

The Chatsworth tragedy dislodged a long standoff on Capitol Hill over the costs and benefits of a PTC mandate, and Congress quickly enacted the Rail Safety Improvement Act of 2008, which included a mandate that all U.S. railroads install PTC by December 31, 2015.

However, the original 2008 law neglected to order the Federal Communications Commission to expedite its procedures for approving siting and licensing of the estimated 17,700 new radio towers that would be needed for full PTC implementation. Also, the original law did not provide for radio spectrum to be made available for the PTC systems (much of the needed spectrum had already been sold off pre-2008, particularly in urban areas, and had to be re-acquired on the open market – and you can’t order a radio system to be built until you know what spectrum on which it will operate). This caused several years of delays, along with the usual factors of shortage of supplies, contractors, trained labor, etc. (see this 2013 GAO report for more details).

And Congress didn’t appropriate much money to pay for railroads to implement the expensive new technology. (A one-time $50 million appropriation in 2010 and another $11 million in 2014 were the extent of it.) In September 2015, realizing that no railroads were in condition to meet the looming deadline, Congress enacted section 1302 of P.L. 114-73 extending the deadline by three years with the potential for another two-year extension after that at the Transportation Secretary’s discretion if a particular railroad had made significant progress.

A few weeks later, the FAST Act of 2015 provided a one-time $199 million slug of funding for PTC grants to commuter railroads and also made let passenger railroads use that money to pay the credit risk premium (if necessary – it isn’t always) for special low-interest, 35-year federal loans to cover the cost of PTC implementation. At this time, passenger railroads (almost always owned by taxpayers, whether federal or state) are lagging farther and farther behind freight railroads (who have already spent about $8 billion of their own money implementing PTC) in the implementation process.

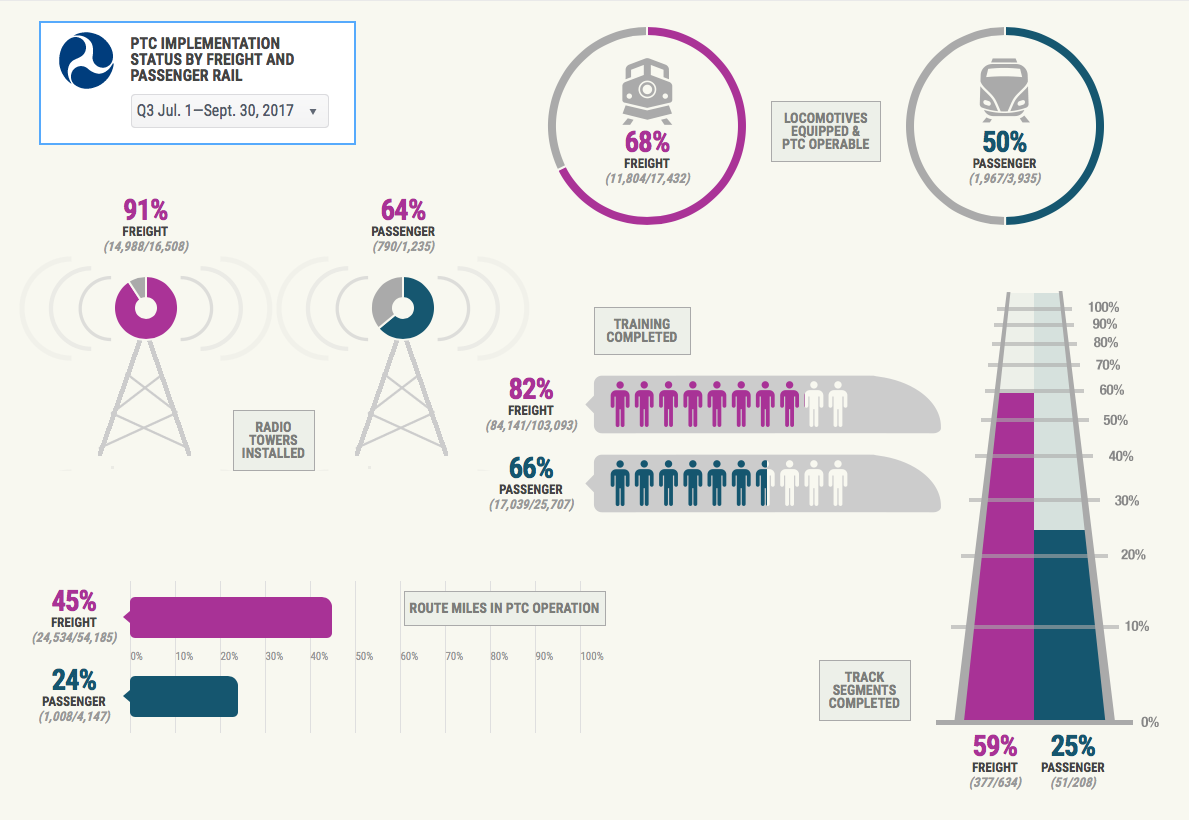

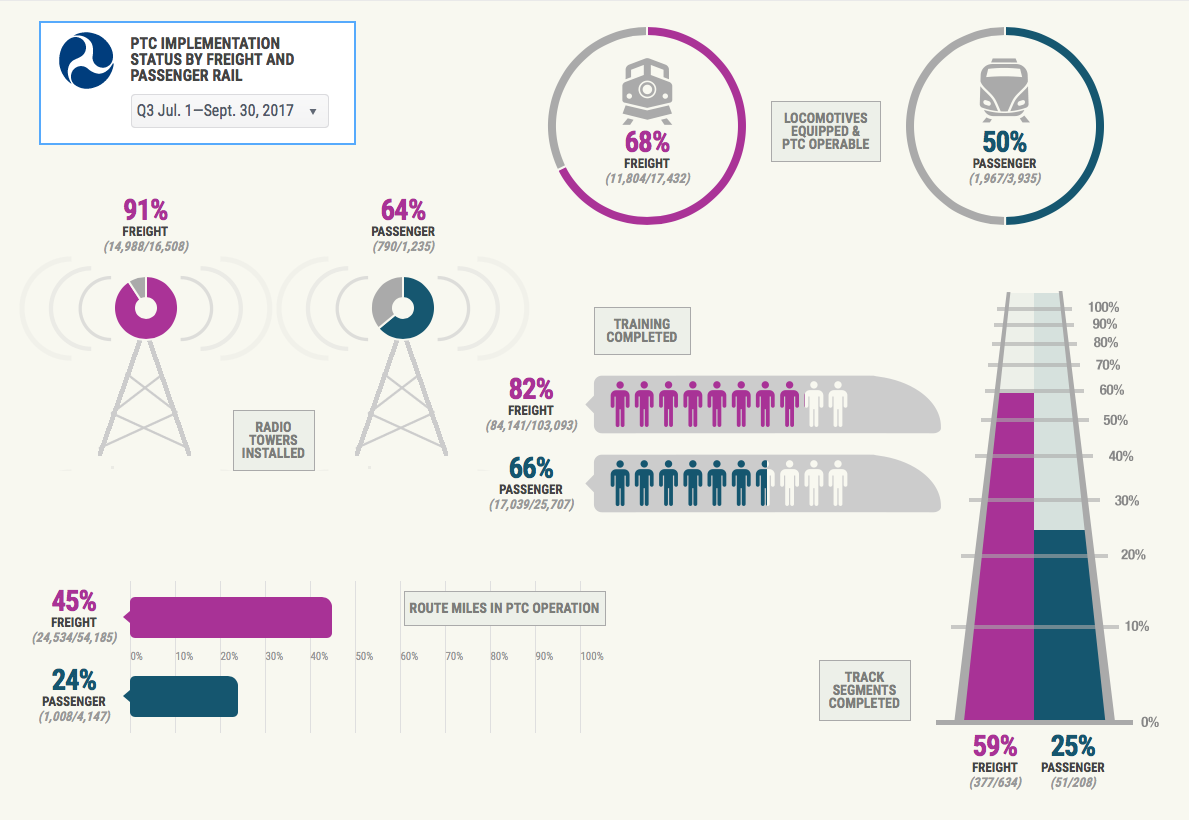

FRA has a handy dashboard website showing how much progress each individual railroad has made in implementing PTC. Most freight railroads appear on track to meet the December 2018 deadline, and most commuter railroads do not. (Ed. Note: Did some commuter railroads drag their feet on using their own funds to implement PTC in the hopes that the federal government would eventually come along and pay for most or all of the PTC implementation costs themselves? Maybe…)

Who decided to start service now? The new Point Defiance Bypass was paid for by the federal government using money from the ARRA stimulus law in 2009, as were the new Siemens locomotives used on the route purchased by Washington State. Because the whole point of the stimulus was to get money into the economy quickly, all of the transportation money in the bill had use-it-or-lose-it deadlines. The high-speed and intercity passenger rail money had the longest deadline, but all of the $8 billion had to be obligated by September 30, 2012. A separate provision of underlying federal law (31 U.S.C. §1552) provides that “On September 30th of the 5th fiscal year after the period of availability for obligation of a fixed appropriation account ends, the account shall be closed and any remaining balance (whether obligated or unobligated) in the account shall be canceled and thereafter shall not be available for obligation or expenditure for any purpose.” So Washington State had to spend every dime of the money (outlays and reimbursement, not just signing contracts) for the route before September 30, 2017. (See this recent ETW article for details on how $248 million of ARRA HSR money was lost on September 30.)

This explains why Washington State was in such a hurry to complete construction. It does not explain whether or not anyone at Amtrak or Washington DOT performed any kind of safety analysis weighing the pros and cons of starting the service as soon as possible after construction was complete versus waiting until Sound Transit (in cooperation with Amtrak, the operator, and BNSF, the signaling dispatcher) had completed installing PTC systems on the new bypass, which is scheduled for sometime in the second quarter of 2018.

Was the design of the route safe? The design of the Point Defiance Bypass requires trains to lose more than half of their speed in a fairly short distance as they prepare to make the turn to cross over Interstate 5. This kind of geometry has been on the minds of safety regulators for some time. In December 2013, a Metro North commuter train in the Bronx did the exact same thing (maintained a circa-80-mph speed into a 30 mph curve) and derailed, killing four people. In May 2015, an Amtrak train near Philadelphia was speeding (106 mph in an 80 mph zone) and then failed to slow down for a 50 mph curve and derailed, killing eight people.

In response to the Metro North accident, the Federal Railroad Administration issued a specific Emergency Order 29 for Metro North requiring Metro North, and only Metro North, to catalog each curve on their routes that required a slowdown of more than 20 miles per hour and develop specific safety plans for those areas. After the later Amtrak crash in Philadelphia, FRA issued Emergency Order 81 requiring that Amtrak follow similar rules (on the Northeast Corridor). FRA also issued a non-binding advisory (Safety Advisory 2015-03) to all other railroads that recommended the following practices:

(3) Survey their entire systems, or the portions on which passenger service is operated, and identify main track locations where there is a reduction of more than 20 mph from the approach speed to a curve or bridge and the maximum authorized operating speed for passenger trains at that curve or bridge (identified locations)…

(5) If the railroad does not utilize an ATC, cab signal, or other signal system capable of providing warning and enforcement of applicable passenger train speed limits (or if a signal modification would interfere with the implementation of PTC or is otherwise not viable), all passenger train movements at the identified locations be made with a second qualified crew member in the cab of the controlling locomotive, or with constant communication between the locomotive engineer and an additional qualified and designated crew member in the body of the train. If the railroad is required to implement PTC at the identified locations, implement these recommended changes in the interim.

Amtrak has not yet responded to an inquiry as to whether or not the train that derailed was being operated in compliance with Safety Advisory 2015-03. There are reports that a second person was in the cab with the engineer but not whether or not that person was a “qualified crew member.”

The FRA safety advisory was non-binding, but six months later, Congress enacted section 11406 of the FAST Act (“Speed limit action plans”), which required much the same thing as the first part of the advisory. All railroads had six months to identify all places where a slowdown before a curve of more than 20 mph was required and submit a safety plan to Congress for each such place. FRA was then required to submit a report to Congress (sent up in May 2016) evaluating all the safety plans. FRA found that “virtually all” railroads had responded positively to the safety advisories but also noted:

FRA believes that until PTC is implemented and in widespread use across the commuter and intercity passenger railroad systems in this country, these railroads and railroads that host passenger service need to continually evaluate their systems to ensure that processes and procedures are in place that enable warning and enforcement of the maximum authorized speed for passenger trains at high-risk locations. In addition to PTC, FRA will continue the effective RSAC process with passenger railroads to explore ways of preventing or reducing passenger train over-speed derailments at curves, bridges, and tunnels.

However, the provision in the FAST Act only applied to routes that were in existence as of the date of enactment of that law and did not apply to new service added since then, like the Point Defiance Bypass. The extent to which Sound Transit and Amtrak have a similar speed limit action plan for that curve is not yet clear.

Were the trainsets safe, and did FRA perform adequate safety oversight here? For proponents of advanced passenger rail in the United States, few things are more frustrating than the fact that railroads can’t just purchase the kind of trains that work so well in other countries and bring them here. This is not just a Buy America problem, but also a feature of longtime Federal Railroad Administration crash safety standards that require passenger rail cars operated in the U.S. to be heavier and more robust than those in use in other countries. This was a particular issue for Amtrak’s Acela – the Canadian-French consortium that built the Acela trainsets had to make the cars twice as heavy as foreign rail cars, which led the French engineers to call the cars “le cochon” (the pig). The weight of the trains caused reliability problems with brakes and chassis as well.

Amtrak’s Cascades line, on which this week’s derailment occurred, is an exception. The Cascades line (running from Eugene, Oregon to Vancouver, British Columbia) has an exemption from the crash safety regulations dating back to 2000 to allow the operation of lightweight Talgo trainsets along the route. The whole discussion of the waiver process can be found by going to www.regulations.gov and entering docket number FRA-1999-6404 (a lot of it hinged on arguments between Talgo’s lobbyists and their competitor Bombardier’s lobbyists). Because the Cascades route is so mountainous, weight was a serious factor, so the decision was made by FRA to let the lighter Talgo trains operate on the route, subject to restrictions, including:

Amtrak must operate the rail cars in dedicated trainsets as proposed in Amtrak’s petition. When operating in revenue or deadhead service, the baggage and end service cars shall be placed at the ends of the remaining cars in the trainset and must not be occupied by passengers or crew members.

The trainsets may be operated in either locomotive-hauled or push-pull service. In locomotive-hauled service, the trainset may be followed by a locomotive-type cab control car (e.g., de-powered F40) at Amtrak’s election. In push-pull service, revenue and deadhead trains must be operated with a locomotive or locomotive-type cab control car on both ends. In either locomotive-hauled or push-pull service, additional equipment in the train consist (e.g., passenger cars, freight cars, materials handling cars, and bi-modal equipment) is prohibited.

But those permissions were only valid along the old Cascades route. On September 6 of this year, Amtrak requested permission from FRA to operate the lightweight Talgo cars along the new Point Defiance Bypass (technically called Sound Transit’s Lakewood Subdivision). On November 24, FRA published a Federal Register notice inviting public comment on Amtrak’s request, and that comment period is still open until January 8, 2018. But on December 14, FRA went ahead and gave Amtrak approval to use the Talgo trainsets on the new bypass even though the FRA letter noted that “In the current request, while Amtrak provided an overview of the Lakewood Subdivision, it did not provide a similar risk assessment, analysis of the proposed operating conditions, or a comparison to the current operations.”

The FRA letter ordered Amtrak to provide a written summary of safety test results on the new route within 30 days of the date of the letter and ordered Amtrak to provide a quantitative risk assessment of the new route within 60 days of the date of the letter. But the train derailed within four days of the date of the letter. (Reminder: the public comment period is still open, and could now get interesting.)

Were engineers given adequate training time on the new route? In the absence of PTC or other kind of automatic signaling system, engineers have to rely on the posted speed limit signs. But there is no substitute for having operated a train over that route repeatedly and knowing where the curves are. One aspect of the crash that the NTSB will focus on is whether or not the engineers had enough training runs along the new route (some news reports indicate that the bypass had only been open for training runs for a few weeks). Running empty trains for training purposes is expensive, both in terms of man-hours and equipment (since a train can’t be in service and in training use at the same time, and there aren’t that many trainsets for use in the Cascades area). Rail labor unions have complained in the past that Amtrak and other railroads have been skimping on such training.

What next for PTC? Washington State transportation officials told the Seattle Times yesterday that no more Amtrak trains would run on the new bypass until PTC is fully installed and implemented. The officials would not admit that the lack of PTC was a safety concern (because that might open them up to more legal liability) – they couched the decision in terms of sensitivity to public opinion.

The revised nationwide PTC deadline is now only slightly over one year away. As noted above, while the big freight railroads look like they are in good shape to meet the deadline, many commuter railroads have made little to no progress and will probably be requesting another deadline extension from Secretary Chao in a year. Meanwhile, there is a lot of work for FRA to do in harmonizing standards and overseeing implementation of safety plans in the crucial final year (GAO will soon report on all the actions that FRA needs to take during the final stretch run). Yet the nomination of the FRA Administrator is being held up by Senate Minority Leader Schumer (D-NY) over unrelated issues.

To the extent that it comes down to money, some commuter railroads that may have slow-walked their tough budget decisions in hopes that a (Hillary) Clinton Administration would wind up paying for their PTC costs are now in a bind. More railroads may need to do what the NYC MTA did in 2015 (in concert with Metro North and the LIRR) when it took out a massive $967 million federal RRIF loan to cover its PTC implementation costs. While grants are always preferable to loans from the recipient’s point of view, publicly-owned railroads can sometimes avoid the most problematic part of the RRIF loan program (the requirement that loan applicants pay their own loan subsidy costs a.k.a. credit risk premiums) for PTC loans. The MTA was able to borrow $967 million for PTC at an interest rate of 2.38% over 35 years with a credit risk premium of 0.00% (see loan documents here). This is literally as cheap as money gets, and it gives commuter railroads the ability to borrow money for PTC implementation at the same exact ultra-low rate that the U.S. Treasury can borrow on the bond market.