One of the few good things about the Highway Trust Fund’s insolvency is that it has caused the old “donor state” problem to recede into the background. Once the Trust Fund became overly dependent on deficit spending (printing money to deposit into the Fund in lieu of real taxes, to be paid for by borrowing on the bond market when the money is spent), the issue of whether or not a state was getting back at least 95 percent of its tax payments became irrelevant – they all were.

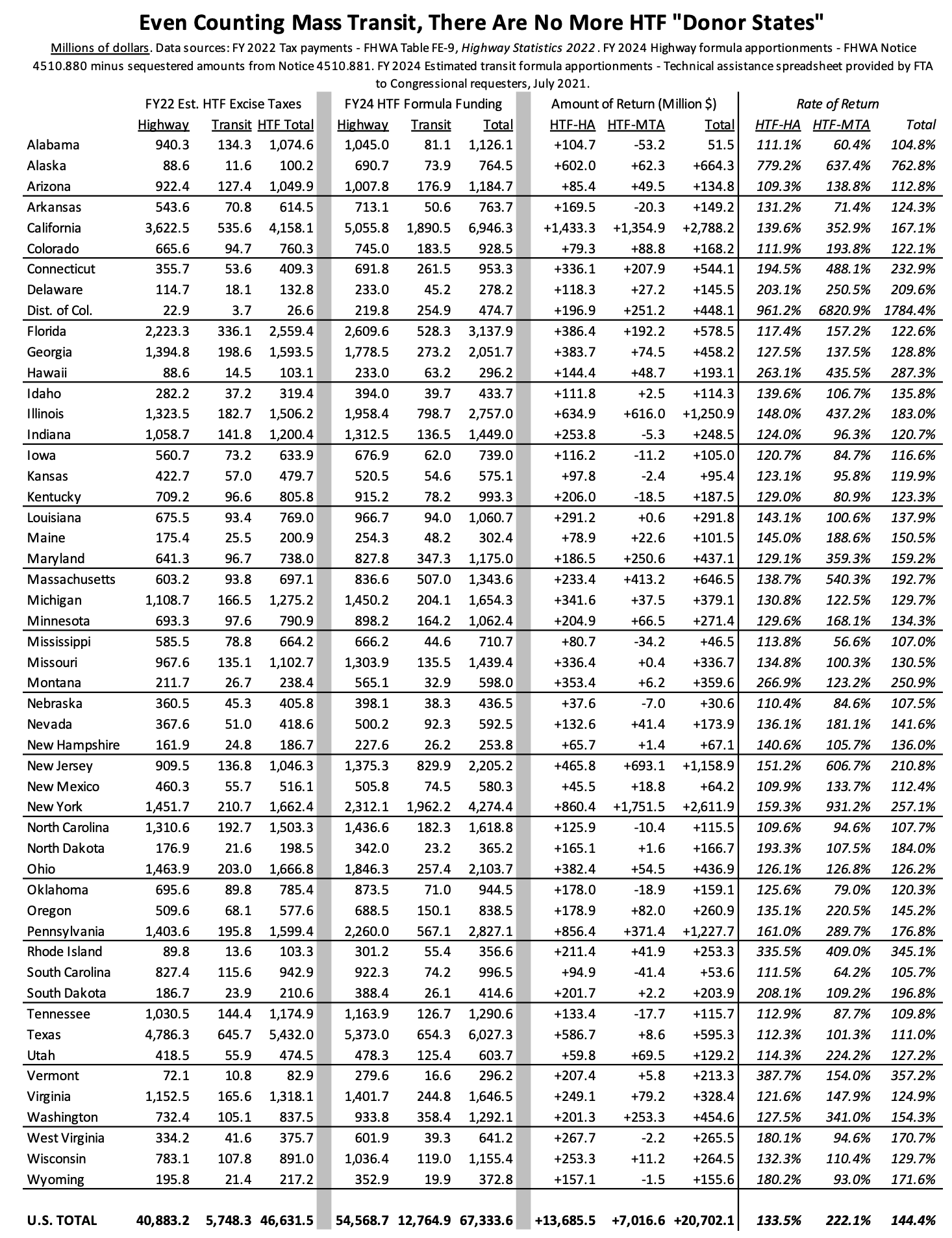

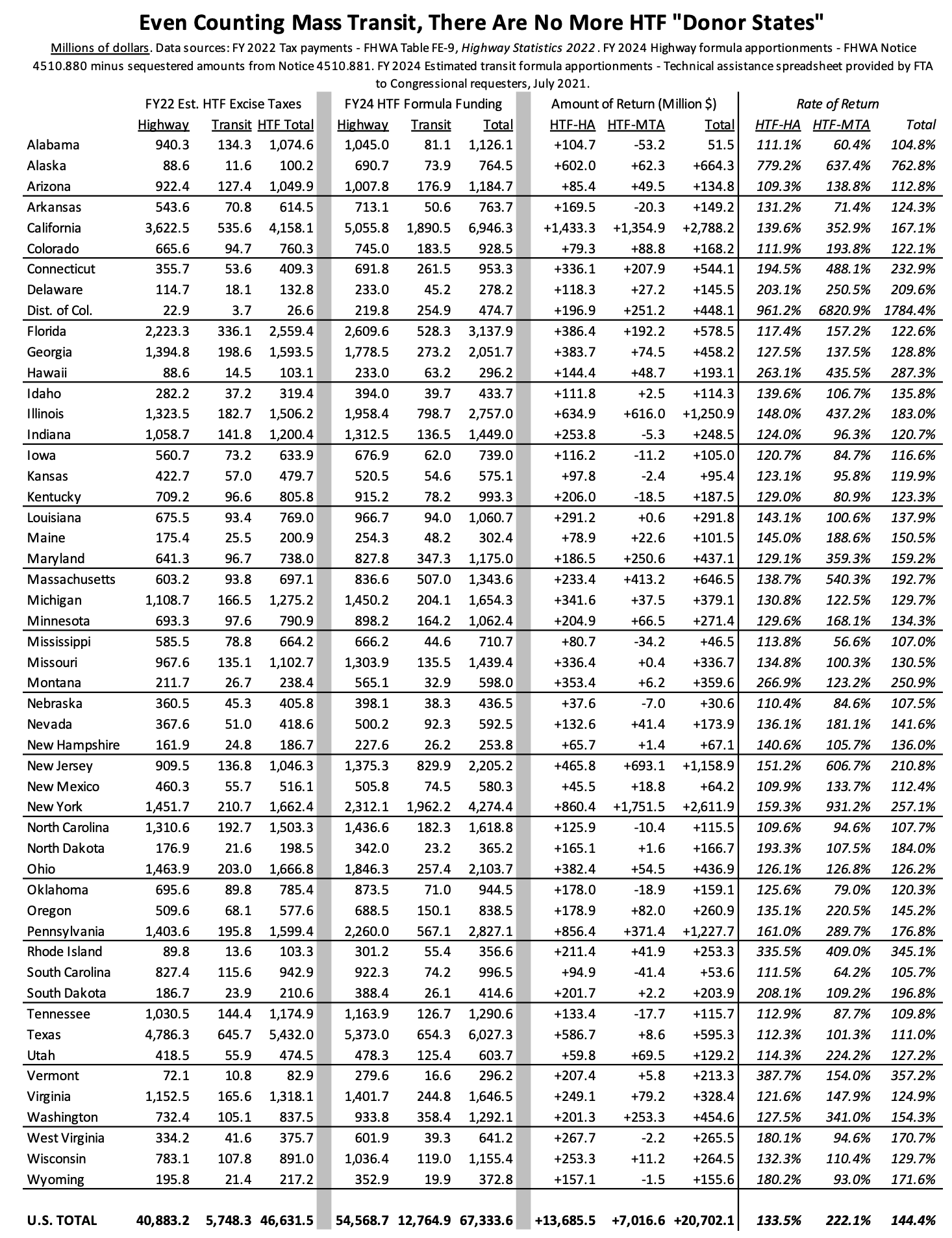

The Federal Highway Administration recently released the latest update for Highway Trust Fund tax payments attributed to states, this for fiscal year 2022. It shows that the Trust Fund is so imbalanced that even after you count mass transit spending, every state gets more than they put in, sometimes much much more.

We compare the 2022 tax payments to 2024 spending because that is how the calculation works. Treasury doesn’t know how much total tax receipts come into the Trust Fund until mid-October, and it takes FHWA months of consultation with state sales tax authorities, VMT measurement, and related computer modeling to attribute tax payments to each state. But formula apportionments have to be ready to go out on October 1, so the 2021 tax data were used to determine the donor state guarantee in the 2023 apportionments, 2022 for 2024, etc.

In the aggregate, in FY 2022, Trust Fund user tax receipts totaled $46.6 billion. But FHWA and the Federal Transit Administration will apportion $67.3 billion in Trust Fund formula funding in 2024, $20.7 billion more than the taxes.

Within the Highway Account, new formula apportionments exceed user taxes by $13.7 billion, ranging from Nebraska’s $37.6 million profit to California’s $1.4 billion profit. And this is formula apportionments only – it does not count money spent directly by the federal government for roads on federal lands, or roads on Indian reservations, or competitive grants like INFRA, or TIFIA credit, or research projects, or any other FHWA funding, so each state’s final take will be higher.

In the Mass Transit Account, the imbalance between dedicated tax receipts and spending is even more off-kilter. $5.7 billion in taxes is expected to support $12.8 billion in new formula spending. If you look at the Mass Transit Account in isolation, there are “donor states” there, in states that don’t use much transit. Mississippi, South Carolina, Oklahoma, Kentucky, and Iowa have particularly low rates of return, while the states where there is a lot of mass transit use (New York, California, New Jersey, Massachusetts, D.C.) receive many times their Transit Account tax payments.

But once you add the Highway Account and Transit Account together, any states that were losing money on the Transit Account are more than made whole by the size of their Highway Account profit. Alabama has the lowest combined rate of return, at 104.8 percent. Texas, usually the leading complainer about their longtime donor state status, has a combined rate of return of 111 percent (they actually have enough transit now that they make a profit on the Transit Account as well). The national average is a 144.4 percent rate of return.