As a child, our founder, William P. Eno, got caught in a horse and buggy traffic jam in Manhattan. This moment apparently affected little Eno so much that he cited this as his metaphorical “Ah-hah” moment. From that point on, he decided to make it his life’s mission to solve the challenges associated with traffic. Imagine a rush hour traffic jam so horrible that you quit your day job and dedicate the rest of your life to solving it. That’s the type of moment this was for Eno.

Eno realized that in order to solve this problem there needed to be a defined set of parameters, or rules, to dictate how the various transportation modes of the day interacted on the streets.

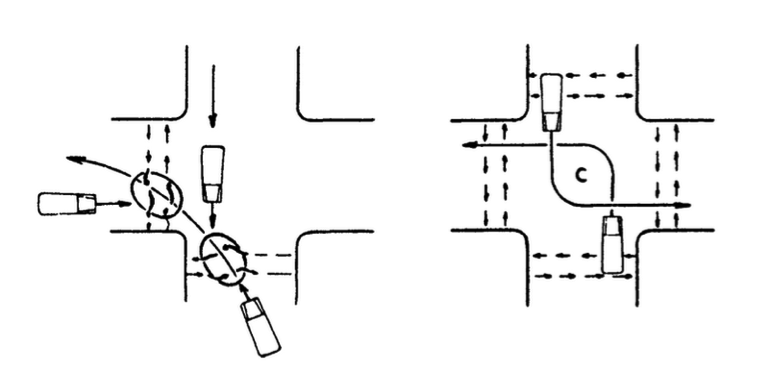

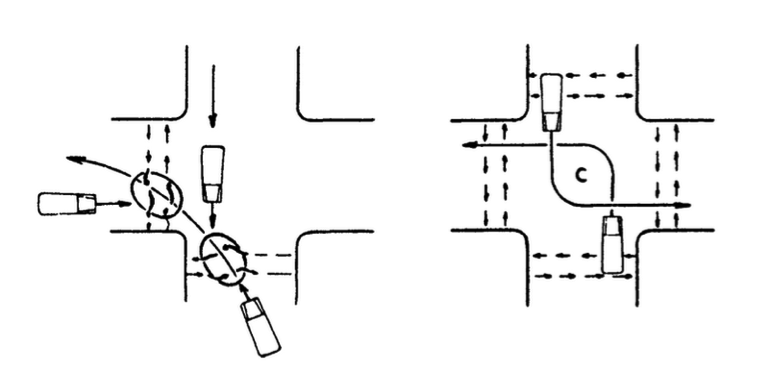

In pursuit of a safer road system Eno developed the hard left-turn, where a vehicle goes into the middle of an intersection to wait to make a left turn at the appropriate time. Eno is also credited with developing the first rules of the road, adopted by New York City in 1909. These rules became the world’s first traffic plan.

(Eno’s hard left turn, photo credit: National Safety Council via Vox.com)

However much has changed since the early 1900s. Today we have a very different urban environment; there are more cars and they are travelling at higher speeds, an ever-growing urban population, new technologies and technology-enabled services, a growing number of people travelling by cycling and walking, and horses are no longer part of the equation.

Last week, on November 12, the Eno Center for Transportation (Eno) held its 18th annual policy summit in Washington, DC to explore how the changing urban and technological landscape has changed the rules of the road, and how policy and policy makers should respond to the changing climate of the roadway.

Eno Interim CEO and President Emil Frankel kicked off the event with words of welcome. Following, Paul Lewis, Eno Vice President for Policy and Finance, provided context of the Rules of the Road.

Neil Pedersen, Executive Director of the Transportation Research Board, opened the day’s first panel asking how all modes could be accommodated on our road infrastructure. Martha Roskowski, Vice President of Local Innovation at People for Bikes, mused that, “in this country we assumed that bikes were little cars or were pedestrians.” She elaborated that this approach does not work and bikes should have facilities designed with their needs in mind.

Representing UPS, Tom Jensen highlighted that while the role of freight is often overlooked in urban environments, it is extremely crucial. Gene Hawkins, guru of the Uniform Vehicle Code – a set of traffic rules prepared since the 1920s by the private non-profit National Committee on Uniform Traffic Laws and Ordinances, – suggested that the code should have the ability to adapt to changing conditions.

The panelists also explored how to define the “rules of the road.” Roskowski noted that the current rules are often written from the perspective of drivers, not bikers or pedestrians. Taylor Reiss Gouge, of New York City Department of Transportation’s Select Bus (NYC’s version of bus-rapid transit with dedicated bus lanes, signal priority, and off-board fare collection), stressed the need to be able to codify new rules in an understandable way for the users. Gouge citied the case of New York City’s new street designs (for example, its bus lanes painted in red) as an approach to using design to complement the existing legal and regulatory framework.

Bud Wright, Executive Director of the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO), noted that the rules of the road should provide a consistency of expectations in order to better serve their goals, i.e., users should be able to infer rules according to context, not having to memorize (or guess) rules for specific situations. Stressing this latter point, Hawkins discussed the role of personal and group expectations when talking about these matters. For example, drivers want signals to enter a main roadway near they house, but dislike signals to allow other people further down the road to enter that main roadway.

In terms of the current framework of rules, Roskowski mentioned the need to tidy up guidelines around bikes. She cited the example of what has been done in this regard in the Netherlands, who has made most neighborhood roadways mixed-used roadways with very low vehicular speed. Hawkins discussed the dichotomy of convenience versus safety, as many of the proposed rules might be more convenient for some users, but might make the system unsafe for other. Gouge, on the other hand, mentioned the need of uniformity and consistency in the rules of the road to make the system more understandable and therefore easier to follow.

Pederson also questioned how enforcement of the rules could be improved. All the panelists noted that enforcement is a challenge. Roskowski argued that enforcement might not be the answer, mostly because it is impossible to enforce every single rule of the road all the time. Gouge added to that the focus should be on designing “self-enforcing” facilities, where the design “forces” the users to follow rules.

In the framework of the various modal interests on the road, the second panel questioned how the increasing influence of technology would further complicate the rules of the road. Sam LaMagna of Intel opened noting that our current physical infrastructure cannot handle everything that it is going to be subjected to in the next couple of decades. He also noted that we should focus on guidelines, not rules, as the former are flexible and the latter static.

Rit Aggarwala of the newly formed Sidewalk Labs, a Google funded company that aims to use technology to solve urban challenges, discussed the auto-industry’s role, and how its culture, generally aimed at selling cars not providing mobility, is ill-suited for the current digital landscape. He also mentioned the role of government, and how its institutions are very slow in adapting to change. For example, he suggested that new systems like Uber or Car2Go should be eligible for public subsidies, as they provide mobility, but the current institutions are too static to deal with that change in paradigm.

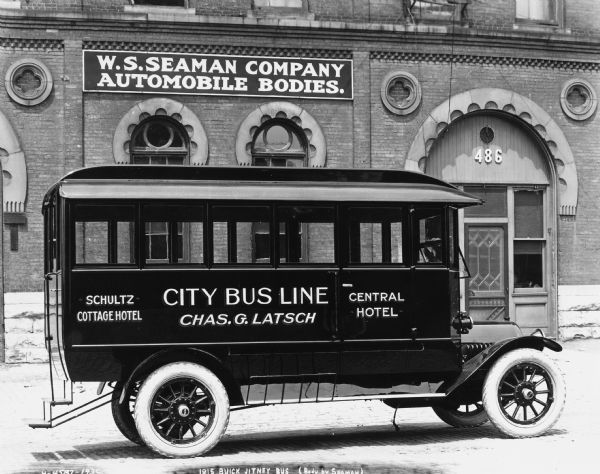

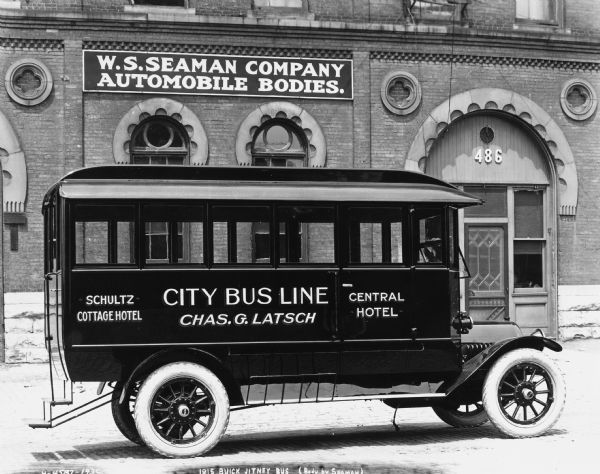

A 1915 Buick Jitney Bus for the Milwaukee City Bus Line. Its body was produced by the W.S Seaman Company. Via the Wisconsin Historical Society

Dan Winston, co-founder of DC based technology enabled transit company Split and current employee of Transdev, and Mike Debonville of Car2Go, also explored the new landscape of technology-enabled mobility. Winston commented that Split has roots in flexible services offered in the United States in the early 20th century, where small jitney buses abounded (see image at left), and which still have a presence in many countries. Debonville noted that Car2Go, a one-way car-sharing system present in many cities across the world, is about providing mobility.

Seleta Reynolds, the general manager of Los Angeles Department of Transportation (LADOT) provided a luncheon keynote speech. She presented the LA experience with changing patterns in urban mobility, and what government needs to do to adapt to people’s demands for streets that are more than roadways designed for maximum vehicle throughput.

Among the initiatives that LADOT is pursuing is LA’s version of Vision Zero, to reduce traffic fatalities to zero by 2025, making biking and walking safer with street design and traffic calming initiatives, create a bike-sharing system with fare integration with existing transit alternatives, and the use of new technologies to manage traffic in real-time. Reynolds also stressed that since a considerable number of Angelinos (around one-sixth of the households) do not have access to a car, there is a need to provide viable transportation options to this significant segment of the population.

The afternoon featured a competition of innovative ideas to improve interactions on the road, called The Great Upheaval. The competition featured five competitors, including graduate students, young professionals, and university professors, pitching their ideas to a jury composed of Jim Burnley of Venable (and a former Secretary of Transportation), Sam LaMagna of Intel, and Howard Jennings from Mobility Lab. Elizabeth Bastian and a team composed of a number of students in her cohort from the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, Masters of Urban Planning program, won the competition. Jinhua Zhao, assistant professor in the Department of Urban Studies and Planning at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, won second place.

In upcoming weeks ETW will be publishing a series of articles exploring each of the finalists proposed ideas in detail, as well as thoughts on the future of the rules of the road from our panelists.