July 13, 2017

Last month, a report (dated from May) from the Working Group On Improving Air Service to Small Communities was made publicly available. This working group was established by section 2303 of the last Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) extension in September 2016 (P.L. 114‐190) and consisted of 25 people nominated by the Secretary of Transportation.

The issue of air service to small communities has been a constant topic of discussion at least since passenger services were deregulated in 1978: before then, airlines were forced to serve whatever communities the Civil Aeronautics Board told them to serve, but with deregulation airlines became free to serve whichever places they wanted to. That led to fears that deregulation would cause many small communities would lose service, which in its turn led to Congress creating the Essential Air Service (EAS) program, which subsidizes air service between (very small) communities and medium and large hubs, as part of the deregulation law. According to studies cited on the report, the EAS program contributed to 23 direct and 31 indirect jobs in each of two airports studied (Clarksburg, WV and Kearney, NE), leading to $4.1 million in annual local economic output.

In the last few years other factors amped up the fears of these communities losing air service. One of them was the wave of mergers in the airline industry—the argument being that these new mega-carriers (four of which control 80% of the domestic market) would be less interested in serving small communities and would focus service on large metropolitan areas; additionally these carriers have also been replacing 50-seat aircraft with larger aircraft, making the economic case to serve small communities harder. The other was the new requirements to become a commercial pilot that Congress enacted following the crash of Colgan Air 3407 in 2009—while before 2013 it was possible to get a commercial pilot license with as few as 250 hours of flying, now, except for a few exceptions like military pilots, it requires 1,500 hours of flying time. This new rule has led to concerns that there would be a shortage of pilots for regional carriers, which are the carriers that mostly serve these small communities. Overall, out of a forecasted need of 50,000 pilots for the next decade (for both regional and mainline carriers) only 34,000 new pilots are expected to be available for hire.

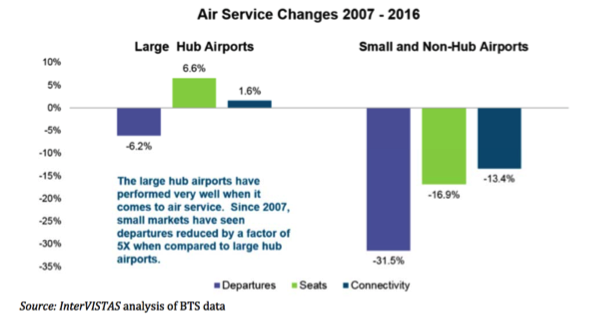

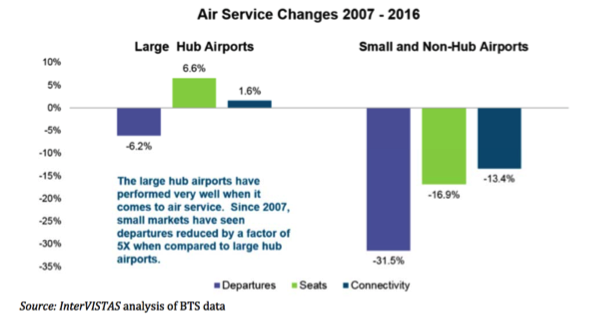

The report presents some interesting statistics about the current state of affairs. For one, as the figure at right shows, small and non-hub airports (as defined by the FAA) lost 31% of scheduled departures, 17% of seats, and 13.4% of total connectivity (we are not sure how “connectivity” is here defined).

The report presents some interesting statistics about the current state of affairs. For one, as the figure at right shows, small and non-hub airports (as defined by the FAA) lost 31% of scheduled departures, 17% of seats, and 13.4% of total connectivity (we are not sure how “connectivity” is here defined).

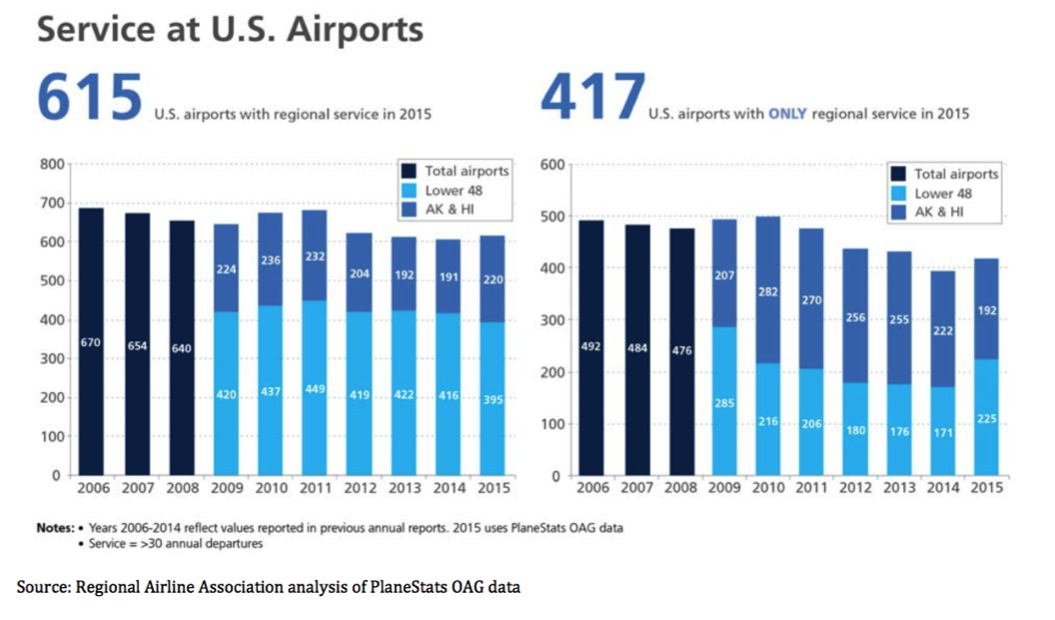

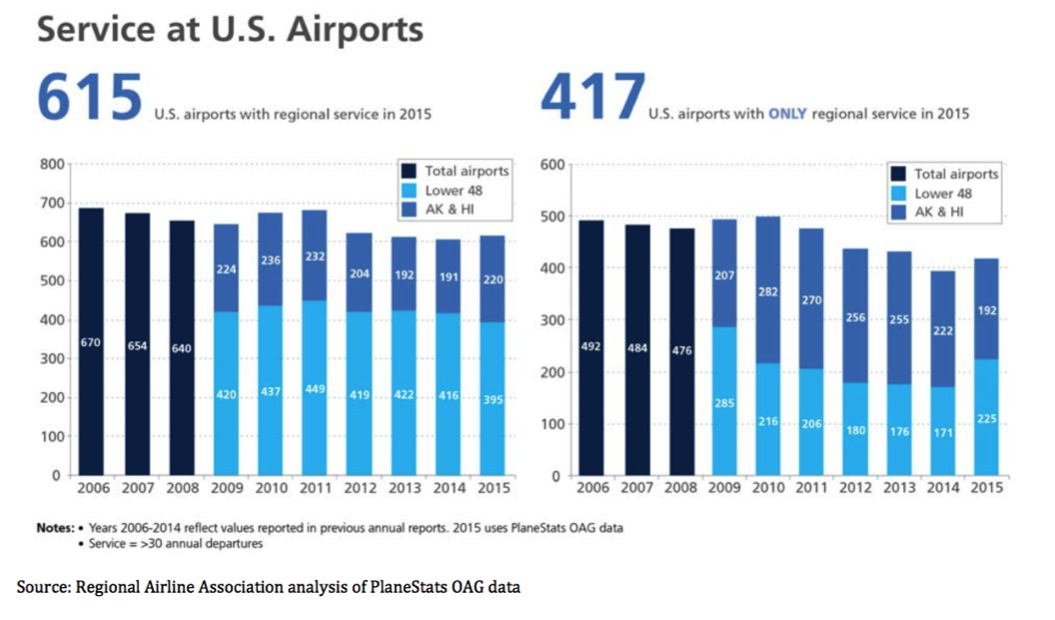

Regional carriers are the only provider of service in 65% of U.S. airports with scheduled passenger service (figure below) and operate 44% of flights in the U.S.

The commission made a total of 21 recommendations, of which we highlight a few.

- Congress should direct the FAA to make more things counts towards the 1,500 hours. The goal would be make the 1,500 hours more about competency and quality of flying that just the quantity of hours logged. (Ed. Note: after some intense discussion the Senate did exactly that with an amendment in the recent mark up of their FAA reauthorization, but the full Senate may revisit this when the bill goes to the floor.) On the pilot shortage, the report also recommends increasing the borrowing limit for student loans for students getting a commercial pilot license.

- More community involvement in the EAS program, namely allowing a community receiving EAS service to complain to U.S. DOT about the quality and reliability of the service being provided and mandate a review of that service. There were a couple more recommendations on EAS, one of them telling Congress to keep EAS as it is and only consider changes after the pilot shortage is solved, and one recommending the creation of a commission to study which communities should and shouldn’t be eligible for EAS (the communities receiving EAS had to be eligible to receive subsidized service way back in 1978 when the program was created, and once they lose their spot in the program they are not allowed back in).

- Remove FAA rules that prohibit airport officials in being involved in efforts to attract air service to their communities. For example, if a local chamber of commerce or visitor bureau is working in attracting airlines to their community, airport officials are prohibited from taking part in those efforts and cannot work in these community efforts.

- Prohibit the FAA “from placing unfunded safety or security mandates upon public use airports. Any new regulations and requirements must be accompanied by funding or a waiver process. “ Additionally, allow airports to bypass NEPA and only follow state environmental requirements for projects that generate non-aeronautical revenue.

- Changes to the Airport Improvement Program (AIP), including the reduction of the local match for non-hub and non-primary airports from 10% to 5% (this is also on the current Senate FAA bill).

- Create tax incentives for manufacturers to develop more aircraft carrying between 9 and 50 passengers.

- If Congress removes the Passenger Facility Charge (PFC) cap (currently at $4.50), the working group recommends that a cap should exist for any passengers coming from a small hub, non-hub, or non-primary airport travelling through large and medium hubs.

The report can be accessed here.

The report presents some interesting statistics about the current state of affairs. For one, as the figure at right shows, small and non-hub airports (

The report presents some interesting statistics about the current state of affairs. For one, as the figure at right shows, small and non-hub airports (