October 4, 2018

At a public event this morning, Transportation Secretary Elaine Chao released her department’s long-awaited “AV 3.0” guidance document, formally called Preparing for the Future of Transportation: Automated Vehicles 3.0. The new document supplements but does not replace the 2.0 version released in September 2017. DOT also requested public comments on the document, due 60 days from today.

Secretary Chao said “the safe integration of automated vehicle technology into our transportation system will increase productivity, facilitate freight movement and create new types of jobs.” Her remarks also emphasized the potential for safety improvements and in the quality of life for the elderly and disabled that could potentially be brought about through widespread use of AV technology.

Video of the rollout event is here.

Like the 2.0 version, 3.0 is a voluntary guidance document (the word “voluntary” occurs no less than 54 times in the document). In particular, it doubles down on the “voluntary safety self-assessment” (VSSA) process established in 2.0 in lieu of legally binding federal safety standards: “U.S. DOT encourages entities to make their VSSA available publicly as a way to promote transparency and strengthen public confidence in ADS technologies.”

But unlike 2.0, the new version is holistic and addresses automation issues throughout all of DOT’s surface transportation modes – 2.0 was almost exclusively about the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration and self-driving cars, while the new document deals with commercial vehicles, intermodal facilities, and mass transit vehicles as well (rail is also mentioned, but just barely, and only in the context of getting rail-highway grade crossing equipment to interact with AVs).

One of the key features of this “One DOT” approach is the announcement that the various modal administrations will begin the process up updating their regulatory definitions of the words “driver” and “operator” to clarify that those words don’t always have to mean a human being. (Again, the Federal Railroad Administration will not be doing this, but NHTSA, the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration, the Federal Highway Administration, and the Federal Transit Administration will be doing so.)

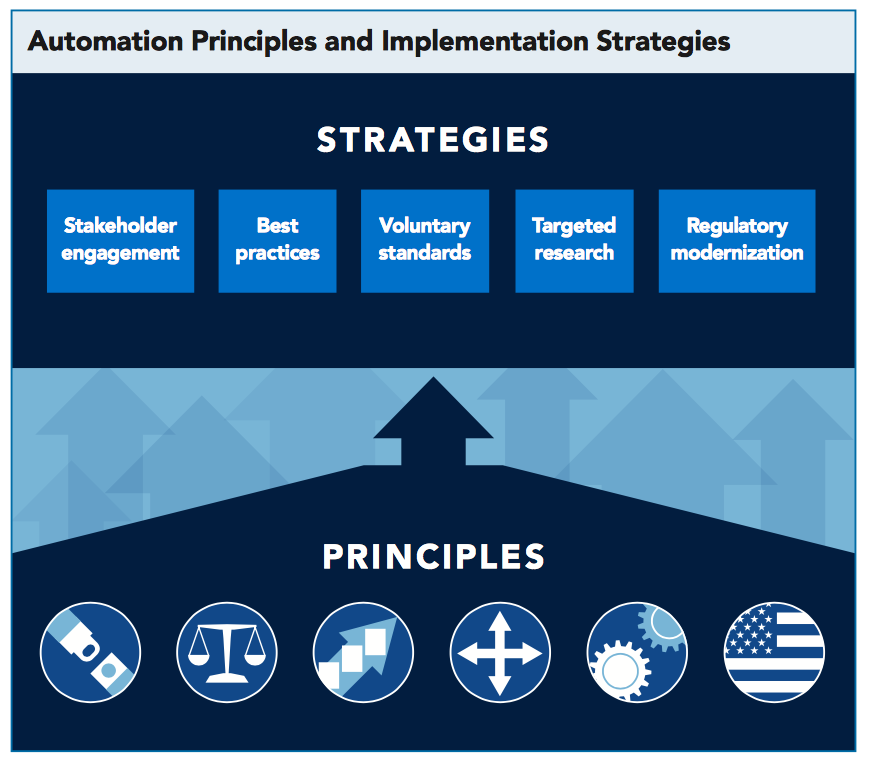

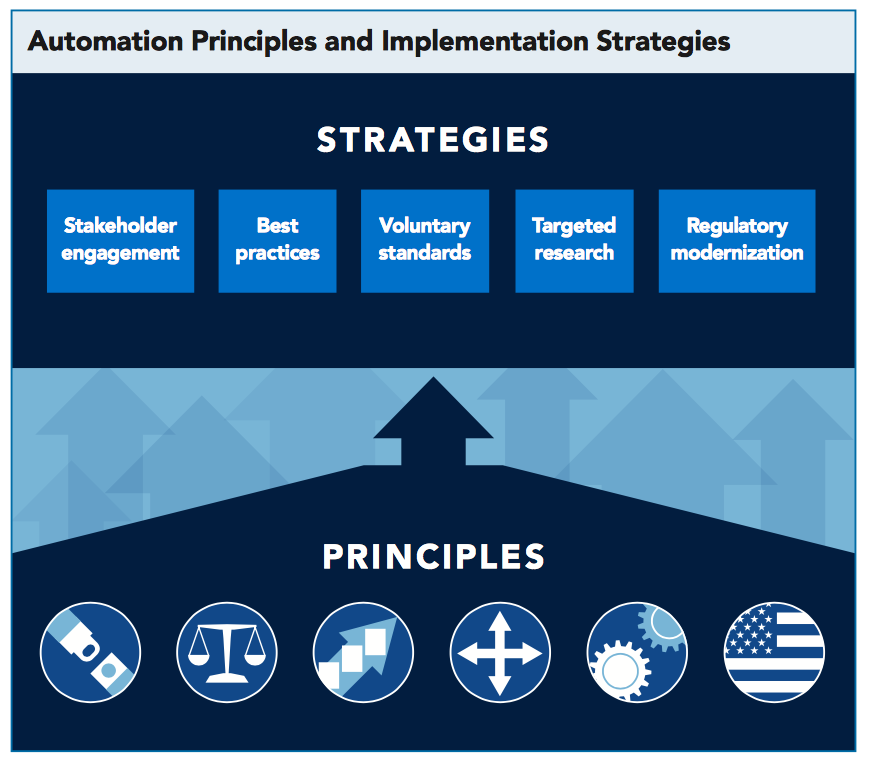

The AV 3.0 document cites six principles that are then to be translated into five different implementation strategies:

| PRINCIPLES |

STRATEGIES |

| 1. Prioritize safety |

1. Stakeholder engagement |

| 2. Remain technology-neutral |

2. Best practices |

| 3. Modernize regulations |

3. Voluntary standards |

| 4. Encourage a consistent regulatory and operational environment |

4. Targeted research |

| 5. Prepare proactively for automation |

5. Regulatory modernization |

| 6. Protect and enhance American freedoms |

|

Specific principles don’t connect to specific strategies, as the nifty graphic from the 3.0 document makes clear:

The 3.0 document encourages state governments to think twice before regulating AVs: “State legislatures may want to first determine if there is a need for State legislation. Unnecessary or overly prescriptive State requirements could create unintended barriers for the testing, deployment, and operations of advanced vehicle safety technologies.”

Setting all of the policy aside, the AV 3.0 document is extremely useful as a reference source – in the back of the document, Tables 1 and 2 in Appendix C list every single existing AV-related standardization document and every known ongoing attempt for standardization by the International Standards Organization, the Society of Automotive Engineers, and others.

In terms of specific actions, the AV 3.0 summary document outlines a number of next steps that the Department will take, some of which were also made official today:

AV collaborative research pilot program. NHTSA has released an Advance Notice of Proposed Rule Making seeking public comment on how it should structure a proposed collaborative AV safety research program. The document lists four areas of focus:

- “potential factors that should be considered in designing a pilot program for the safe on-road testing and deployment of vehicles with high and full driving automation and associated equipment.”

- “the use of existing statutory provisions and regulations to allow for the implementation of such a pilot program.”

- “any additional elements of regulatory relief (e.g., exceptions, exemptions, or other potential measures) that might be needed to facilitate the efforts to participate in the pilot program and conduct on-road research and testing involving these vehicles, especially those that lack controls for human drivers and thus may not comply with all existing safety standards.”

- “the nature of the safety and any other analyses that it should perform in assessing the merits of individual exemption petitions and on the types of terms and conditions it should consider attaching to exemptions to protect public safety and facilitate the Agency’s monitoring and learning from the testing and deployment, while preserving the freedom to innovate.”

Public comments will be due within 45 days of the notice actually being printed in the Federal Register (which could come later this week).

Change the definition of “operator” for CMV regs. The Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration will issue a document within the next two months asking for public comment on which of its voluminous motor carrier safety standard regulations will need to be revised to make it clear that the “operator” of a commercial motor vehicle is not always required to be a human being.

Change NHTSA standards to allow cars without driver input. The 3.0 document notes that current safety standards make it illegal to sell cars that lack driver input features like steering wheels, brake and throttle pedals, mirrors, etc. Because the eventual manufacture of stage 4 and 5 AVs won’t need those features, “In an upcoming rulemaking, NHTSA plans to seek comment on proposed changes to particular safety standards to accommodate automated vehicle technologies and the possibility of setting exceptions to certain standards—that are relevant only when human drivers are present—for ADS-equipped vehicles.”

Fast-tracking the NHTSA exemption process. The 3.0 document says that NHTSA “intends to seek public comment on a proposal to streamline and modernize procedures the Agency will follow when processing and deciding exemption petitions. Among other things, the proposed changes will remove unnecessary delays in seeking public comment as part of the exemption process, and clarify and update thetypes of information needed to support such petitions.”

$60 million in grants for AV testing. In conjunction with the release of AV 3.0, NHTSA will soon be soliciting applications for the $60 million in AV testing grants provided in the fiscal year 2018 omnibus appropriations bill. The formal notice will appear in the Federal Register in a few weeks and was not finished in time for today’s announcements.

AV testing money will be open to all. The 3.0 document makes clear that the Trump Administration has little use for the designation of ten sites as AV proving grounds and will instead allow anyone to apply for funding. The AV proving grounds were designated by Transportation Secretary Anthony Foxx on his way out the door (almost literally – the designations were announced on the day before the Trump inauguration following a selection process that did not begin until November 29, 2016).

The new document says “given the rapid increase in automated vehicle testing activities in many locations, there is no need for U.S. DOT to favor particular locations or to pick winners and losers. Therefore, the Department no longer recognizes the designations…”

To some extent, this may run afoul of the intent of Congress – the explanatory statement for the omnibus directed the $60 million to “be used for grants and cooperative agreements to fund demonstration projects that test the feasibility and safety of HAV and ADAS deployments” and said that local governments “including entities designated as automated vehicle proving grounds” can apply for funding. So Congress specifically made non-designees eligible for funding. However, the statement also says that suit of the $60 million, “the Secretary is directed to award no more than $10,000,000 to a single grantee, no more than $15,000,000 to grantees within a single state, and not less than $20,000,000 to entities designated as automated vehicle proving grounds.” It is, as yet, unclear how DOT will thread this particular needle.

Updating the MUTCD. The 3.0 document says that the Federal Highway Administration will begin the multi-year process of updating the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (which last got a comprehensive upgrade in 2009) to reflect changing technology for vehicle-to-infrastructure and vehicle-to-vehicle systems. The Manual is the official compilation of national standards for all traffic control devices, including road markings, highway signs, and traffic signals. A FHWA representative at the press event said that the changes will include ways to mark signs and lanes to make them more readable for computer cameras, but could also include other kinds of “smart infrastructure.”

Transit bus guidance. The 3.0 document says that “FTA is preparing guidance to provide stakeholders with clarity on existing FTA rules relevant to developing, testing, and deploying automated transit buses.”

Port access. While automated ships are closer to being a reality right now than are automated cars, the Department of Transportation does not have legal jurisdiction over the safety of ships (that is the Coast Guard’s purview). But the 3.0 document does mention what happens once a ship docks: “Currently at many of the Nation’s busiest ports, commercial vehicle drivers must wait in slow-moving queues for hours to pick up or deliver a load. MARAD and FMCSA are evaluating how automation might relieve the burden on a driver under these circumstances, and, in particular, the regulatory and economic feasibility of using automated truck queueing as a technology solution to truck staging, access, and parking issues at ports. The study will investigate whether full or partial automation of queuing within ports could lead to increased productivity by altering the responsibilities and physical presence of drivers, potentially allowing them to be off-duty during the loading and unloading process.”

Study of workforce impacts. Secretary Chao also announced that DOT, along wth the Labor, Commerce, and Health and Human Services Departments, will begin a comprehensive study of the impacts of automated vehicles on the workforce. This was telegraphed in the 2018 omnibus appropriations act, which provided $1.5 million for such a study. A draft Federal Register notice released today requested public comment on the scope of the study. The notice lists four areas of study:

- Labor force transformation studies including potential statistical models to generate estimates of labor force effects given various HAV and ADAS adoption/timeline scenarios and segments of freight and passenger transportation that could be affected.

- Labor force training needs including minimum and recommended training requirements, labor market programs that link workers to employment and public or private training programs to address skill gaps.

- Technology operational safety issues impact to situational awareness caused by HAV and ADAS including options for reducing safety risks of reduced situational awareness and visibility, mobility, and safety issues related to platooning.

- Quality of life improvements due to automation including mental fatigue related to traffic and queueing; enhanced travel choices, new job opportunities, and accessibility leading to independent travel and workplace access for people with disabilities, older adults, and individuals with functional impairments across the lifespan.