August 3, 2016

Last month, like every month, Tennessee’s Highway Safety Office (HSO) joined numerous agencies across the United States in urging its residents to put their phones away while driving.

This was not an unusual plea from transportation officials, but their social media messaging involved a surprisingly agile response to a timely concern: Pokemon Go, a smartphone game that took the U.S. by storm, has presented a new obstacle for safety officials attempting to reduce distracted driving in their state.

Responding to concerns that drivers would take their hands and eyes off of the wheel to play Pokemon Go triggered the below public safety advisory from Tennessee HSO on July 8.

(Source: Tennessee Highway Safety Office)

The post seemed hauntingly prophetic after a truck driver was killed in Knoxville, Tennessee on July 20 after colliding with a wrong-way driver, since initial reports suggested the driver was playing Pokemon Go.

Although the claims were unsubstantiated, and have since been refuted by the Knoxville Police Department, the incident reflects growing concerns about distracted driving across the U.S.

As numerous studies have shown, distracted driving is not simply a matter of stray hands and averted eyes – it is about occupied minds. Because the game requires relatively low-level engagement from players, the concern is that they may be lured into a false sense of attentiveness.

In Wisconsin, authorities have reported that two individuals playing Pokemon Go and driving while intoxicated to have caused two non-lethal accidents. As a response to what was perceived as an uptick in distracted driving, Wisconsin’s DOT activated this warning on its highway signs:

In Wisconsin, authorities have reported that two individuals playing Pokemon Go and driving while intoxicated to have caused two non-lethal accidents. As a response to what was perceived as an uptick in distracted driving, Wisconsin’s DOT activated this warning on its highway signs:

Eliminating cell phone use while driving, particularly texting or calling without hands-free devices, was a top priority of former U.S. Transportation Secretary Ray LaHood and other transportation safety officials – even leading to the creation of Distraction.gov by USDOT.

As smartphones have become more sophisticated, drivers are also using their phones for functions that fall into a gray area when it seems justifiable – namely for navigation and using Transportation Network Company (TNC) platforms.

Particularly troubling is that TNC apps do not allow their drivers enough time to safely pull over, accept a fare, and safely activate navigation to their passenger (typically drivers must accept within 10 seconds). If a TNC driver consistently misses fares (e.g. if they’re caught in difficult driving situations in the urban core and cannot take their hands off the wheel to accept the ride), they face penalties levied by the platform and potentially being booted off of their system.

Same Old Song and Dance

Smartphones and applications like Pokemon Go may be new, but distractions posed by technology behind the wheel have been an issue for nearly a century.

In the 1930s it was the radio: concerned citizen George A. Parker led a campaign to prohibit car stereos in Massachusetts just as they were beginning to explode in popularity. A prohibition was also proposed in Missouri while legislators also proposed imposing fines for using car radios in Ohio, New York, New Jersey, and Illinois.

These initiatives ultimately failed in all but a few small municipalities. Yet the Auto Club of New York in 1934 still found that 56% of people believed car radios to be a “dangerous distraction.”

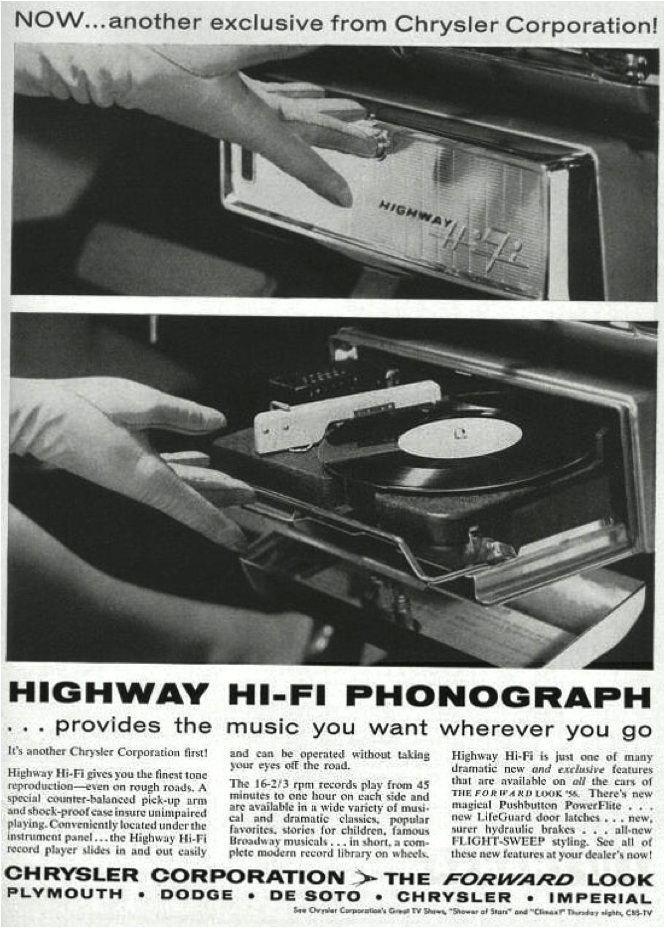

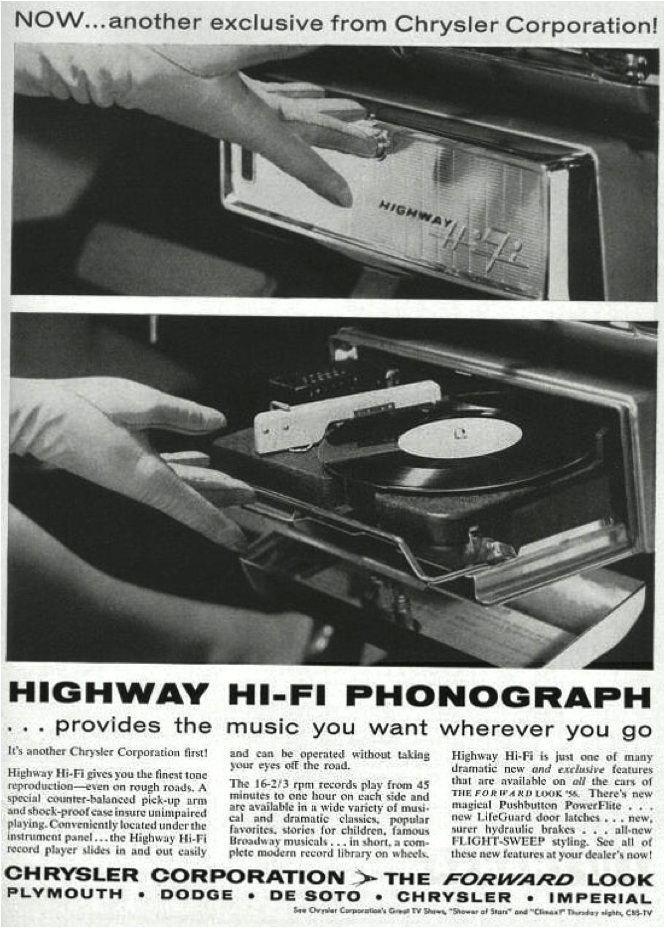

Source: UAW-Chrysler.com

A couple of decades afterwards, Chrysler introduced the Highway Hi-Fi Phonograph, which provided a brand new, much more complicated distraction. Two critical (yet unsurprising) issues tainted the under-dash record player’s short-lived existence in the Fifties and Sixties: the needle wouldn’t always stay on the record and it was not safe to operate it while driving.

The Highway Phonograph seems comical compared to the less-involved systems that followed, including the eight-track tape deck, cassette players, and eventually CDs. (It should be noted that the federal government did not gain full legal authority to regulate vehicle safety until 1966.) Yet all of these serve as a valuable reference point for understanding drivers’ excessive confidence in their abilities and limitless sources of potential distraction.

Distracted Driving Today

Distracted driving was recorded a factor in 10% of fatal crashes and 18% of crashes resulting in injuries in 2014. This resulted in 3,179 lives lost and an additional 431,000 injured, according to NHTSA.

In an effort to prevent this senseless loss of life, Congress created a new distracted driving incentive grant program sought by LaHood in the 2012 MAP-21 transportation law. The program (codified in 23 U.S.C. §405(e)) awards grants to states that enact and enforce distracted driving statutes that meet the criteria set out in the law.

On its face, the distracted driving incentive grant program has been a failure so far. In FY 2013, only seven states and Guam were awarded the grant. In FY 2014 and FY 2015, only one state – Connecticut – received it.

The reason, it seems, is that although most states have passed legislation banning distracted driving, those laws have fallen short of meeting the strict criteria that Congress defined in law as requirements to receive the grant, namely:

- Drivers are prohibited from texting while driving (enforced as a primary offense with a progressive fine structure)

- Drivers age 18 and younger must be prohibited from using personal communications devices while driving (enforced as a primary offense with a progressive fine structure)

- Distracted driving issues must be tested as part of the state driver’s license exam

Although states have increasingly focused on distracted driving caused by cell phones and many passed further legislation, Connecticut was still the only recipient of the grant in FY 2016. For the rest of the 49 states, territories, and D.C., the distracted driving incentive money was redistributed among other highway safety formula programs.

In the coming years, combatting distracted driving will be increasingly critical. Research recently conducted by Liberty Mutual Insurance and Students Against Destructive Decisions (SADD) showed that 27% of teens report texting and driving, while 68% admit to using apps while driving.

Among the areas of concern: teens ranked “app-ing and driving” (e.g. using Facebook, Snapchat, Pokemon Go) as much less distracting than either texting and driving or driving under the influence of alcohol. Experts on the effects of such interactions on driver reaction times disagree.

Yet there is still hope. Of the teens surveyed, many (41%) recognized that using navigation apps while driving is dangerous or distracting and even more (64%) said they understood that using music apps is distracting.

Since the foundation of understanding has been laid, Tennessee’s Highway Safety Office may be onto something: scaring teens about the dangers of using apps while driving, while they’re browsing Twitter and driving, could really drive the point home.

Of course, this assumes Tennessee teenagers follow the Tennessee Highway Safety Office on Twitter.

In

In