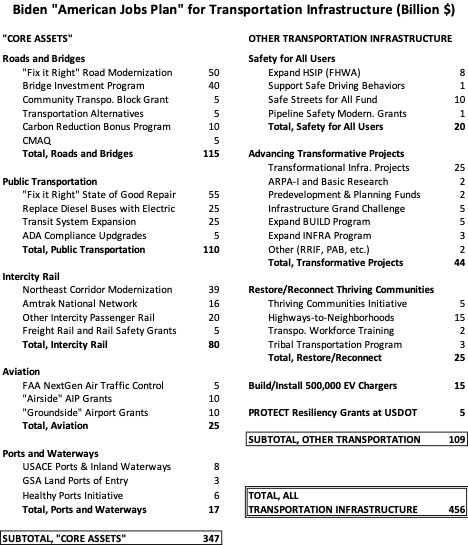

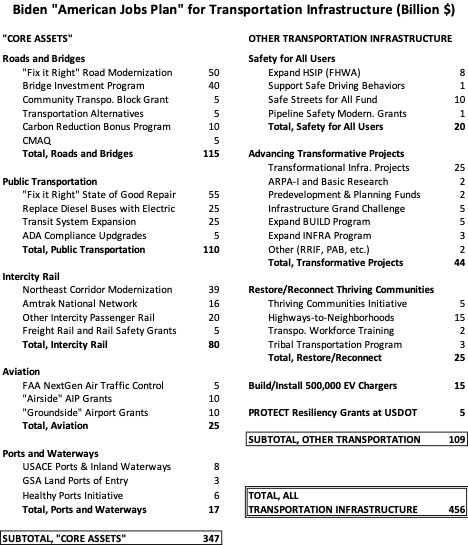

Last week’s rollout of President Biden’s “American Jobs Plan” was limited to one White House fact sheet and a background briefing, neither of which included much of a programmatic breakdown of the $2.3 trillion in funding. But earlier this week, a USDOT official sent a few Capitol Hill offices a breakdown of the $456 billion in transportation infrastructure spending proposed under the plan, which was promptly leaked, first to POLITICO and then, later in the day, to Reuters, which gives a much better idea of how highway, transit, rail, and other types of money proposed to be provided by the legislation would be divided up.

Roads and bridges. The plan calls for $50 billion of the highway money to be given out for state-of-good-repair improvements to roads, which the earlier fact sheet said would “modernize 20,000 miles of highways, roads, and main streets…” This would average $2.5 million per mile of work – see Table A-1 in the most recent Conditions and Performance Report to see how that compares to the average cost of reconstructing an existing lane-mile of road (from as little as $915 thousand per lane-mile for minor arterial roads on flat surfaces in rural areas, up to $7.7 million per mile of Interstate or expressway in major urbanized areas).

The plan also calls for $40 billion for a new bridge program, which the fact sheet says will include the ten most economically important bridges as well as 10,000 off-system bridges. (No word yet on how much of that money goes for the big bridges and how much for all the little ones.)

The big questions here continue to be non-federal share (will states have to match this money with 20 percent of a project cost, 10 percent, zero?), and will USDOT really be picking all these projects on a competitive basis (as the White House seems to indicate), despite the fact that they don’t have anywhere near the staff capacity to discern which are the 10,000 worst-condition small bridges and negotiate project agreements for each one?

The remainder of the money goes towards two new programs and two existing programs. The new programs, for which we have no details yet, are a “carbon reduction bonus program” ($10 billion) and a “community transportation block grant program” ($5 billion).

The two existing formula-based highway programs getting money are the “transportation alternatives” program and the “congestion mitigation and air quality” program, which get $5 billion each. “TA” is the main federal-aid highway funding source for bicycle and pedestrian projects (the program currently gets $850 million per year, for any use prescribed in paragraph (29) of this version of 23 U.S.C. §101, so another $5 billion would be almost six full years worth of TA money at once.

As for CMAQ, this money would presumably have to be exempt from the regular rules that allow states to transfer money between formula programs, because a lot of states don’t like CMAQ. Over the last five fiscal years (2015-2019), federal funding for CMAQ has averaged $2.36 billion per year in new contract authority, but states have collectively only obligated an average of $1.25 billion per year, meaning that almost half of all CMAQ money gets transferred to other programs.

Mass transit. While the White House document says that they are putting $85 billion towards transit, we choose to include the $25 billion from the EV program for diesel transit bus replacement as part of the transit money, not the EV money. (Replacing diesel buses with electric budget is completely duplicative of an existing Federal Transit Administration grant program.) This brings the transit total to $110 billion.

In addition to the electric bus money, the plan calls for $55 billion for state-of-good-repair grants to transit providers. (The big question is the degree to which this program will just incorporate the existing State of Good Repair grant program under 49 U.S.C. §5337. Funding under the existing SOGR program was limited to the 85 largest urbanized areas in FY 2021, with New York City getting 27 percent of the national funding total. Will the Biden Administration spread this new SOGR money more widely, and if so, what will the formula be?)

Unlike highways, where the Biden plan does not seem to envision new capacity, the plan explicitly calls for $25 billion for expansion of mass transit systems. (Funding for new subways, light rail, and bus rapid transit has been averaging just north of $2 billion per year in recent years, so this would be a phenomenal increase on top of that.) The big questions are: how much of this is to be new fixed guideway capacity (the aforementioned subways, light rail, and BRT), versus how much is to be improved bus service? (Bus money goes a lot farther.) And will the new fixed guideway project be run through the existing Capital Investment Grant program, or will a new program be created?

The Biden plan also calls for $5 billion for Americans with Disabilities Act upgrades to older, non-conforming transit systems.

Intercity rail. The detail made available this week answers one burning question about the $80 billion in rail money in the Biden plan – how much would go towards the (federally-owned) Northeast Corridor, versus how much for the rest of the system?

As it turns out, about half of the money ($39 billion) would go towards Northeast Corridor modernization. And this $39 billion could effectively turn out to be more than that, if the $6 billion federal share of the proposed new Hudson River Tunnel, or the $4.5 billion proposed replacement tunnel under Baltimore, wind up getting paid for out of the “megaprojects” pot of money elsewhere in the plan, instead of being deducted from the $39 billion for NEC upgrades.

Another $16 billion would go to upgrade and expand Amtrak’s national network outside the Northeast Corridor. Unlike the NEC, the capital needs of which are almost limitless and which is actually owned by Amtrak, almost all of the National Network moves on tracks owned by freight railroads. Amtrak’s assets are confined to rolling stock (locomotives and railcars) and passenger stations. Amtrak’s latest capital plan only shows a $2.9 billion state-of-good-repair capital backlog on the entire National Network, which leaves $13 billion left over for fleet upgrades and service route expansion.

Concurrent with the release of the Biden plan, Amtrak CEO Bill Flynn released a map of proposed new Amtrak service routes, including new service to cities large (Phoenix, Las Vegas, Nashville, Columbus) and small (Eau Claire, Pueblo, Montgomery, Rockland). (Ed. Note: It is hard to argue that being left without intercity passenger rail service for the last 50 years really held back the growth of Phoenix and Las Vegas.) The plan also called for more frequent service (and better on-time service) on existing National Network routes. $13 billion would go a long way towards that expanded service. The remaining question: would these new routes go through the usual state-support process, and would all those state governors and legislatures really agree to cover the operating losses of those routes in perpetuity?

Another $20 billion would be set aside for non-Amtrak intercity passenger rail. Proposed systems like the beleaguered California high-speed rail project, the Texas Central high-speed rail project, and Brightline’s projects from Miami-Orlando and Las Vegas-Los Angeles could be eligible for shares of this funding. Other projects that are farther down the drawing board could also be eligible, but since the Biden plan is one-time money, there are concerns as to how long the money would remain available.

The other $5 billion would go to “enhance grant and loan programs that support passenger and freight rail safety, efficiency, and electrification.”

Aviation. The new information makes clear that, after taking $5 billion off the top for FAA air traffic control upgrades, the remaining $20 billion for airports will be split 50-50 between the existing Airport Improvement Program that provides grants for new and upgraded runways, taxiways, lighting, safety, and other “airside” improvements, and a new grant program for “groundside” improvements like terminals and multimodal connections to ground transportation that don’t involve parking.

Ports and waterways. Jurisdiction over ports has always been odd. The actual dredging of harbors, and operation and maintenance of inland waterways, is the Army Corps of Engineers, which gets $8 billion towards those purposes. (All spending in the Biden plan is supposed to be above baseline, but the baseline does not reflect the recent agreement to unlock $9 billion in carryover balances in the Harbor Maintenance Trust Fund, so if that money is also spent in the next few years above baseline, we are actually talking north of $16 billion, not $8 billion.)

And ports of entry, on land, are the General Services Administration (just like other federal facilities), which gets $3 billion under this plan to upgrade those.

That leaves the Department of Transportation with the remaining $6 billion, for a “Healthy Ports Initiative,” defined in the fact sheet as a “program to mitigate the cumulative impacts of air pollution on neighborhoods near ports, often communities of color.”

Safety programs. The biggest item here is $10 billion for a new “Safe Streets for All” program which, the fact sheet says, is “to fund state and local “vision zero” plans and other improvements to reduce crashes and fatalities, especially for cyclists and pedestrians.” Another $8 billion goes to supplement the FHWA’s Highway Safety Improvement Program, which already receives about $2.5 billion per year in highway contract authority.

An additional $1 billion is to “Support safe driving behaviors” (no explanation given), and the final $1 billion is for the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration to provide infrastructure modernization grants.

‘Transformative projects.” There is a lot going on under this header. $25 billion is for the big-ticket megaprojects – a “Transformational Infrastructure Projects Fund” that is “to support ambitious projects that have tangible benefits to the regional or national economy but are too large or complex for existing funding programs.” As mentioned above, one of these could be the new Hudson River Tunnel, which is obviously going to get funded under this Administration, somehow. Another $8 billion goes to plus up existing progrmas that fund large surface transportation projects – $5 billion to expand the BUILD multimodal grant program, and $3 billion to expand the INFRA program for large highway projects. (Both of those programs have been getting around $1 billion per year in the regular budget.)

Beyond that, this category contains $2 billion for planning and predevelopment grants, $2 billion for what appears to be a version of ARPA for infrastructure (and other basic research, the example of which from the facdt sheet was “advanced pavements that recycle carbon dioxide”), and $5 billion for something called the “Infrastructure Grand Challenge” that has not yet been defined.

Then the plan calls for $200 million to modernize the existing RRIF lending program (but if that is meant to be loan subsidy authority, $200 million could unlock billions of dollars in additional loans through the normal leveraging process). And it calls for $1.5 billion in on-budget costs for reauthorizing and expanding Private Activity Bonds – but, again, the on-budget costs of expanding the bond program are significantly less than the face value of the bonds themselves.

“Restore and Reconnect Thriving Communities.” The centerpiece of this funding area is $15 billion for a “Highways to Neighborhoods” program, which, from the sound of the fact sheet, revolves around tearing down highways and restoring older neighborhoods, or possibly covering highways in some areas to allow more connectivity.

$5 billion would be for a “Thriving Communities Initiative” (as yet undefined), $3 billion would go towards transportation on Indian lands, and $2 billion would go towards transportation workforce training and “upskilling.”

Electric vehicles. It is now clear that, of the $160 billion in EV money, the bulk ($100 billion) is penciled in for point-of-sale rebates. How far will this go? The previously existing federal tax rebate for an EV purchase capped out at $7,500, which divided into $100 billion would subsidize 13.3 million light-duty vehicles. A $5,000 rebate would subsidize 20 million vehicles, et cetera. This compares to 2020 sales of 14.5 million light-duty vehicles in the U.S. (3.4 million cars and 11.1 million crossovers, SUVs and pickup trucks), of which a little over 300,000 were electric.

Those rebates don’t really count as “infrastructure” spending. (I refuse to believe that the Tesla parked in my neighbor’s garage is “infrastructure.”) And, after setting aside the $25 billion for electric mass transit buses (classified as transportation spending) and the $20 billion for electric school buses (classified as education spending), all of the EV money that is left as “infrastructure” is $15 billion for the installation of EV charging stations.

The fact sheet says that the money would “establish grant and incentive programs for state and local governments and the private sector to build a national network of 500,000 EV chargers by 2030.” That comes out to an average of $30 thousand per charging station.

In addition to the $160 billion in spending, the plan also calls for tax credits totaling $10 billion to incentivize the purchase of medium-duty and heavy-duty electric vehicles, and an estimated $4 billion cost of an expansion of the existing section 30C alternative fuel vehicle refueling property credit.