March 23, 2017

On March 22, Rep. Peter DeFazio (D-OR), the ranking minority member of the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee, introduced a bill to infuse tens of billions of dollars per year into the Highway Trust Fund immediately, to be repaid through annual indexation increases in the federal gasoline and diesel fuel excise taxes.

“Today, I am introducing legislation that will provide approximately $500 billion in additional investment for roads, bridges, and transit systems and fill the hole in the Highway Trust Fund. My bill will address our state-of-good-repair backlog, repair or replace deficient bridges, create tens of thousands of good-paying American jobs, and keep us competitive in the world economy. A Penny for Progress is a straightforward, practical bill that deserves consideration,” DeFazio said in a statement.

The bill is H.R. 1664 – bill text is here, DeFazio’s staff summary of the legislation is here, and a list of organizations endorsing the legislation is here.

The long-term insolvency of the Highway Trust Fund is due to two factors: the lack of any increase in federal gasoline and diesel tax rates since 1993, and the refusal of Congress to restrain HTF spending post-2004 to levels that can be supported by those excise taxes. Periodic actions by Congress to bail out the Trust Fund since 2008, while allowing steady spending increases, make the long-term funding imbalance in the HTF much worse. Once the FAST Act expires in September 2020, the HTF will need extra deposits (either through tax increases or some other kind of deposit) of at least $20 billion per year – forever – in order to stay solvent.

The Congressional Budget Office recently estimated that each cent per gallon of motor fuels tax yields about $1.8 billion per year for the Trust Fund, though that will decrease over the next decade as higher fuel efficiency standards for cars and trucks take effect. In 2027 each cent of fuel tax will only bring in about $1.6 billion. Obviously, if one wanted to start bringing in an extra $20-25 billion per year, a sharp increase would be necessary in the short term.

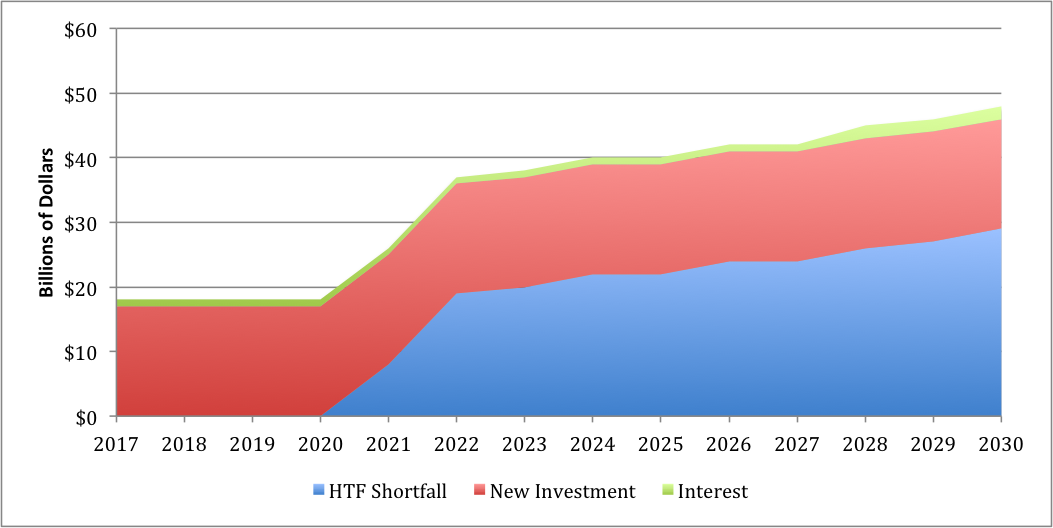

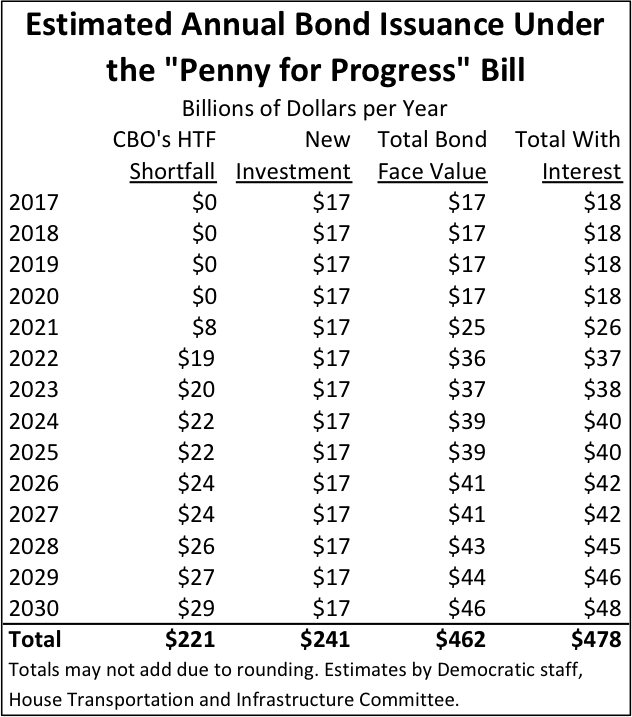

DeFazio’s bill attempts to smooth out the need for revenue increases by limiting the fuel tax increases to no more than 1.5 cent per gallon per year, and borrowing against those future increases to provide an immediate infusion of funding. The Treasury Department would be directed to issue a new kind of 30-year bond (“Invest in America Bonds”) each year, starting in 2017 and ending in 2030. The proceeds of those bonds would be deposited into the HTF (80 percent to the Highway Account and 20 percent to the Mass Transit Account).

A third HTF account, the “Temporary Transportation Bond Repayment Account,” would be created to hold the receipts from the annual increases in the motor fuels taxes that start in 2017, and bond interest and principal would be paid and repaid out of this new account. DeFazio staff estimate the first tranche of bonds would pay an interest rate of approximately 3.6 percent.

The annual indexation amount would be a combination of the annual increase in the Federal Highway Administration’s National Highway Cost Construction Index (NHCCI), if any, and the estimated annual reduction in highway fuel usage attributable to federally mandated increases in vehicle fuel economy standards (CAFE). The annual increase could not exceed 1.5 percent (any increase above that would be spread over multiple years), and the tax could not decrease (there have been sharp year-to-year changes in the NHCCI in the past).

The amount of bonds to be issued each year is not specifically stated in DeFazio’s legislation but is instead based on the needs estimates in modified versions of the Federal Highway Administration and Federal Transit Administration’s biennial “Conditions and Performance” reports. From 2017 through the end of the FAST Act in 2020, the annual amount of bond principal issued would be the difference between the estimated federal share of the highway and transit needs estimate from the C&P report minus the contract authority levels provided by the FAST Act. (The DeFazio bill also repeals the July 2020 highway contract authority rescission provided in the FAST Act so that the bond issuances for FY 2020 won’t jump drastically).

DeFazio’s staff estimates that the face amount of FY 2017 bonds would be $17.2 billion, on top of $55.1 billion already authorized by the FAST Act, a spending increase of 31 percent.

For the 2021-2030 period, the annual amount of bonds issued would be equal to the federal share of the C&P needs forecast minus estimated HTF tax receipts (not including indexation increases caused by the bill). This would mean a sizeable jump in the amount of bonds issued starting in 2021, because FAST Act contract authority will be $58.7 billion in FY 2020 (under the DeFazio bill which cancels the scheduled $7.6 billion July 2020 highway rescission), but HTF tax receipts in FY 2021 are only estimated to be $40.2 billion.

The extra deposits in the HTF each year from the bonds would be apportioned via the existing highway and transit formulas (with the highway money not being subject to some existing set-asides, and with some of the transit money made available for the Capital Investment Grant program, which is not currently funded out of the Trust Fund.)

Overall, the DeFazio idea seems sound – a dedicated revenue stream that allows the repayment of bonds. Real spending would increase in the short term, repaid by real tax revenues in the long term. There is, however, one conceptual problem with the legislation, as well as a few technical problems.

Conceptual problem. The DeFazio bill would issue a special kind of federal bond (still backed by the full faith and credit of the United States, of course) to be deposited in a specific federal trust fund account for the benefit of a few specific federal programs. The Treasury Department as an institution viscerally opposes this kind of special treatment, instead preferring “unitary financing,” defined by a Clinton Administration Treasury official in 1998 this way:

Treasury employs unitary financing. We aggregate all of the Government’s financing needs and borrow as one nation. Thus, all programs of the Federal Government can benefit from Treasury’s low borrowing rate. Otherwise, separate programs with smaller, less liquid issues, would compete with one another in the market. Paul Volcker, then Under Secretary of the Treasury, proposed to promote the concept of unitary financing by establishing the Federal Financing Bank. He brought that idea before [the Ways and Means] Committee 27 years ago. The Administration continues to vigorously endorse this principle.

In 2003, the Treasury Department under George W. Bush objected to Highway Trust Fund bonding legislation proposed by Senators Chuck Grassley (R-IA) and Max Baucus (D-MT) “in the strongest possible terms” and threatened a presidential veto. (See the full letter on page 16 of the July 28, 2003 issue of Transportation Weekly.)

Also, and this is a less important issue, by creating a new HTF account to hold the indexed tax receipts, the DeFazio bill is also creating new federal debt in addition to the bonds themselves, since all HTF deposits are automatically invested in Treasury securities that count towards the public debt subject to limit. The upcoming fight over increasing the debt limit this fall will, no doubt, cast all legislative proposals to increase the public debt into sharp relief.

Technical problems. The technical problems with the DeFazio plan all boil down to the lack of good data from an official federal source presented in the format necessary for the DeFazio bill to work as intended.

- Bond face value calculation. The FHWA/FTA Conditions and Performance reports don’t presently reveal the required federal share of highway and transit needs, instead focusing on the combined federal-state-local expenditure needed to maintain or improve roads and transit systems. Section 4 of the DeFazio bill orders the reports to start reporting the information in a useful way starting in 2018 (presumably this would entail the use of year-of-expenditure dollars instead of the constant dollars currently used), but this won’t be available in time for the 2017 indexation. This is more problematic in mass transit, where there is an ill-defined federal role (there is no officially designated federal-aid mass transit system, and the federal share of new start costs is negotiable, not fixed), compared to highways, where every mile of road on the federal-aid system has a specific federal cost share set in law. The last two C&P reports had their “current spending levels” skewed by one-time ARRA stimulus spending.

- Highway costs. Unfortunately, FHWA has halted release of the National Highway Cost Construction Index after first quarter 2016, and may be rethinking the methodology (again). Without some kind of index, there can be no indexation.

- Fuel economy. The final CAFE rulemaking tables related to fuel usage focus on the fuel saved by car model year over a lifetime, not the fuel saved in each calendar year. This renders them not particularly useful for estimating annual changes in fuel tax receipts due to CAFE, which is the whole point of indexation.

(Ed. Note: In the woulda/coulda/shoulda department, it would have been nice if anyone with a vested interest in the Highway Trust Fund who was also in charge of CAFE standards – like, say, the House T&I Committee or the Senate EPW Committee – had thought to amend the law at any point in the last 40 years to require that any new CAFE rulemaking also include a year-by-year estimate of the effects the higher standards would have on HTF revenues. But no one ever did, and now we have no official data as to just how badly NHTSA and the EPA (at the behest of Congress and the executive branch) are decimating Highway Trust Fund revenues.)

In summary, the Treasury Department can’t be expected to give up on its institutional interest in preserving “unitary financing” without a fight. But the DeFazio plan does represent real money for infrastructure funding paid for (eventually) by real user tax increases, and to the extent there are technical problems with the bill, they serve to illuminate existing problems with the way the federal government collects and presents transportation funding data – problems that need to be solved whether or not DeFazio’s proposal ever goes anywhere.

“Penny For Progress” Annual Bond Issuance, Plus Interest Costs