The precipitous drop in public transit ridership since the outbreak of the COVID-19 virus is well reported. Those of us with the luxury to work from home are doing so and transit officials are in the remarkable position of pleading with customers NOT to ride unless they absolutely have to. As a result, our news feeds are filled with stories breathlessly reporting on transit’s “death spiral” along with unsettling images of empty subway cars and train stations like ghost towns.

Yet it is important to note that it is a big country and transit means different things. While railroads, subways, and buses all operate as part of a holistic transportation network, whom they serve and how they function are different and those differences are playing out in the virus crisis.

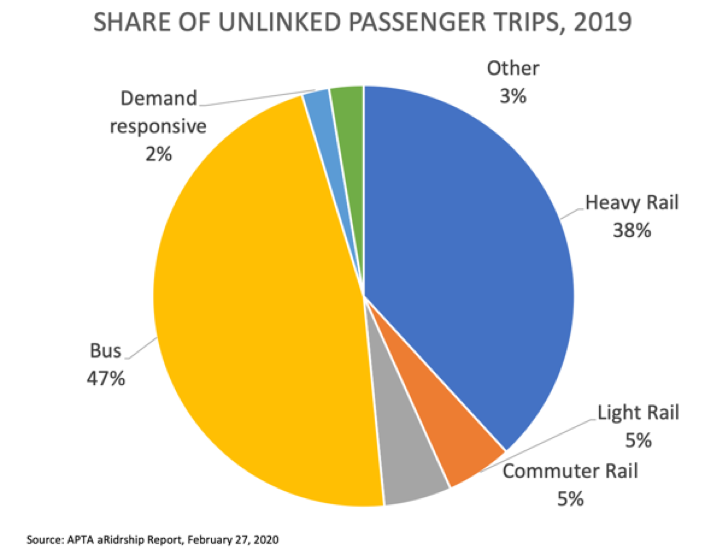

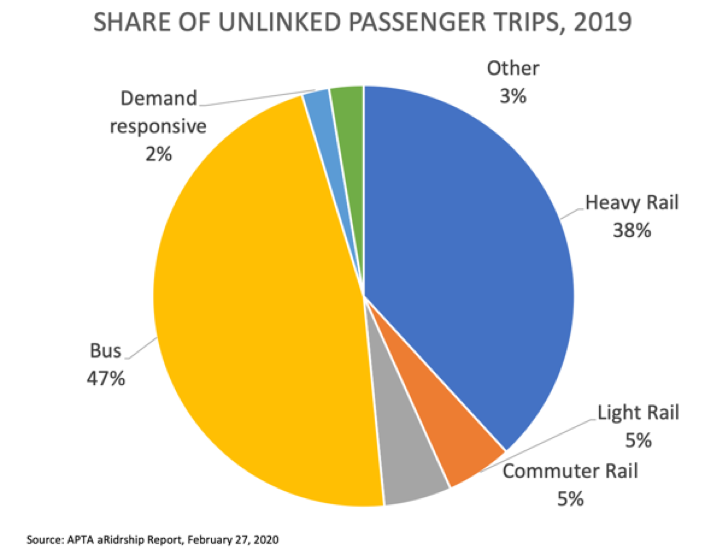

This matters because about half of the nation’s transit users are bus riders, according to the latest data from the American Public Transportation Association. Bus riders are also poorer than other transit riders, meaning they have fewer options for how to get around than others. In other words, a lot of bus riders have no other way to travel, are often essential workers who must physically be in their workplaces, or both. Recent analysis by TransitCenter found that workers classified as essential during the COVID-19 emergency account for 36 percent of total transit commuters in the United States. (We do not know the transit breakdown for these essential workers.)

Commuter rail riders are generally wealthier than other transit users, work traditional business hours (by definition), and can more easily shift to working from home. As a result, commuter rail passengers have all but disappeared during the crisis. Ridership on the New York region’s Metro North commuter rail plummeted 95 percent. Metra – the commuter rail that serves suburban Chicago – is down 97 percent causing officials to wonder if ridership there will ever fully recover. The Port Authority Transit Corporation (PATCO) line in suburban Philadelphia is witnessing similar drops. The Virginia Railway Express is only seeing about 10 percent of its normal ridership and the Tri-Rail line in southeastern Florida saw ridership tumble despite suspending fare collection.

Heavy rail ridership fell nearly as much, led by New York where subway passenger levels are down 90 percent. In Washington, Metrorail is also reduced to a tenth—or possibly less—of its normal riders (which unfortunately comes after ridership increases last year, reversing years of decline.) In San Francisco, the Bay Area Rapid Transit system is looking at a 97 percent decline, much worse than Los Angeles Metro Rail’s decrease of 75 percent.

In contrast, the major bus systems in both Los Angeles and Washington are at about two-thirds of their baseline. St. Louis and Richmond, Virginia are seeing similar statistics with bus down nearly 40 percent. In Connecticut, a state where just as many people ride the bus as rail, bus ridership is about half of normal. In both Baltimore and Pinellas County, outside of Tampa, passenger counts are cut in half. These are bleak figures, but it is worth noting that the numbers are not fractions of what they would normally be, as is the case for rail, illustrating the role of bus as a lifeline. Another example is that there is a big difference between traditional city bus service and rush hour-focused commuter bus express routes—like those in Spokane, Detroit, and Northern Virginia which are down about 70, 80, and 90 percent, respectively.

In fairness, reporters do not have access to super-current ridership data broken down by place, mode, and income. It is also important to note that the figures cited above are difficult to verify, are mostly anecdotal, and often come at different time horizons. Statistics from the last week or March probably look different than they do today.

But the bottom line is that the discussion about what is happening to public transit ridership during this time of quarantine and self-isolation needs to be more specific. It matters because the customers who are served by commuter rail, subway, and bus ridership are different and as attention focuses on how to keep transit agencies operating during and after the recovery—and how to keep transit workers safe while doing do—priority should be placed on the bus. Transit riders and our metropolitan economies depend on it.