The House and Senate kicked off the first formal intercameral conference committee of the current Congress, and the first one in several years. The subject is the mammoth economic competition bill – reconciling the differences between the 3,609-page House bill (H.R. 4521) and the 2,325-page Senate amendment.

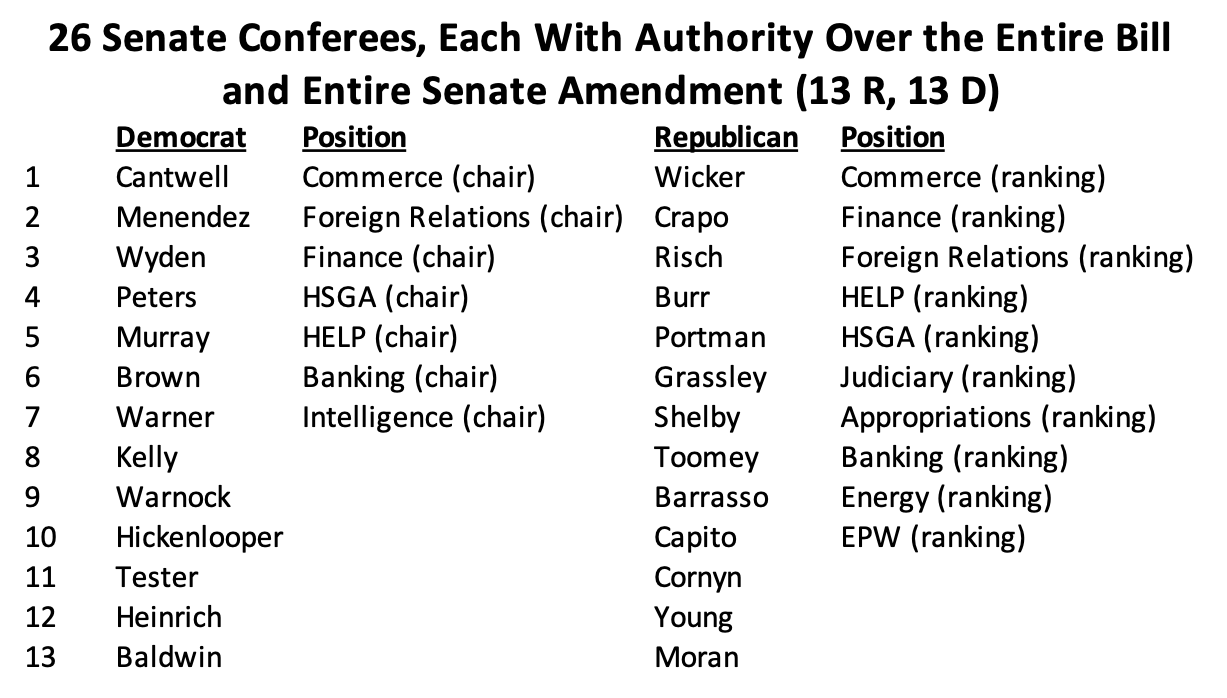

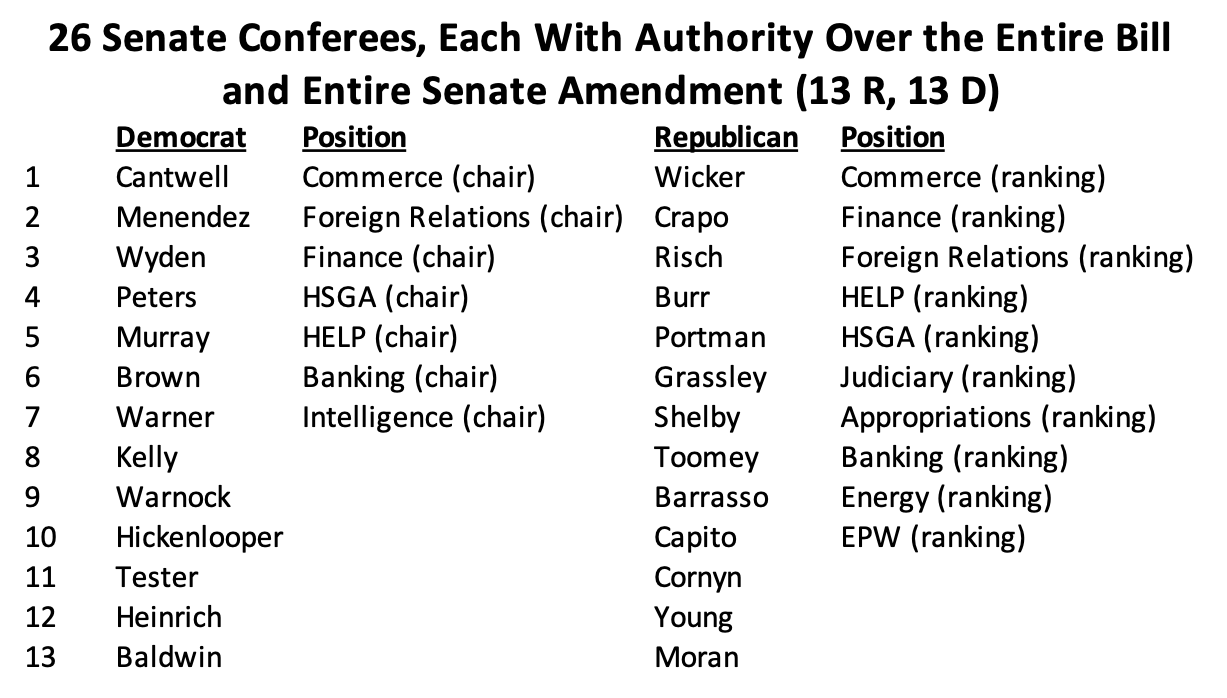

As used to be normal with big, sprawling, multi-committee bills, there are a lot of conferees. The Senate has appointed 26 (13 Democrats, 13 Republicans) and the House 71 (49 Democrats, 32 Republicans).

However, that does not mean that the House has more power, in conference, than the Senate. In a conference committee, there are only two votes: one House vote, and one Senate vote. Each chamber’s conferees vote separately on how to cast their chamber’s vote on a particular issue, if it is framed in public.

But the House and Senate give negotiating authority to their conferees in different ways. In the Senate, every conferee has an equal say over all parts of the matter in disagreement, no matter what committee they represent or what committee an issue falls under. When it comes time to “close out” the conference with a majority of signatures from each side, if Senator Toomey (on the conference in his capacity as ranking member of the Banking Committee) wants to withhold his signature because he does not like something in the Appropriations title of the bill, he can do so. (Senators are strongly urged to stay in their own lane, lest someone else monkey in their jurisdiction as they are doing to others, but it still happens.) If a total of 13 Senators decline to sign the conference report, for any combination of reasons, there is no conference agreement and the bill cannot move forward.

The House does things differently. Some conferees are appointed with jurisdiction over everything, but other conferees have their jurisdiction limited to certain provisions under their committee’s jurisdiction, and nothing else. 48 of the House conferees are general conferees, and then there are 33 other conferees, 3 apiece from 11 other committees, who only have jurisdiction over specific provisions of the House bill and the Senate amendment that are under their jurisdiction.

This works to the disadvantage of the conferees from the secondary committees. For example, for a provision under Transportation and Infrastructure jurisdiction, the signatures of at least 26 conferees are necessary to finalize that provision (26 being the smallest majority of the 51 conferees with authority over the T&I provisions – the 3 T&I conferees and the 48 general conferees). If the general conferees have a bipartisan deal on the big stuff, and at least 26 of the 48 general conferees are on board with the deal, then the signatures of all of the 33 other secondary committees are, technically, irrelevant.

Before the GOP took control of Congress in 1995, the practice from 1975-1994 had been to defer to secondary conferees, and one committee’s conferees could (and frequently did) hold an entire conference hostage over something they wanted. (There is a legendary and possibly exaggerated story about the Energy and Commerce chairman extorting the Public Works and Transportation chairman in the waning hours of the ISTEA conference in 1991. I am going to go to the National Archives and pull up the original filed conference report to check whether a long section in Bob Bergman’s handwriting is on the original paperwork or not.) Newt Gingrich got rid of this when he took over in 1995, and it is one of the Gingrich reforms that Speaker Pelosi chose not to reverse when she took back the Speaker’s chair for Democrats 12 years later.

(Again, there is a strong norm in place to let the secondary committees negotiate their own stuff, lest the shoe be on the other foot someday, but when push comes to judo chop, the general conferees can always steamroll the secondary conferees. And, since the House is a partisan place these days, it’s no surprise that House Democrats gave themselves 27 general conferees – one more than the 26 needed to close out the entire bill themselves.)

The provisions that are under the jurisdiction of the three House Transportation and Infrastructure conferees are:

- Section 70121 of Subtitle B of Title I Division H of the House bill, denying U.S. port privileges to driftnet fishing vessels from nations that are on the State Department’s human trafficking blacklist.

- Subtitle C of title I of division H of the House bill, requiring that fishing vessels over 65 feet in length and operating in U.S. waters have an automatic ID system, and authorizing the appropriation of $5 million for grants to shipowners to install such devices.

- Division L of the House bill, which contains four provisions salvaged from the stalled Build Back Better bill – the “Recompete” grant pilot program at EDA (sec. 110001), the establishment of centers of excellence for domestic maritime workforce and education (sec. 110002), the creation of a Freight Rail Innovation Institute (sec, 110003), and an authorization for $240 million in EDA economic adjustment assistance for communities transiting out of the energy resource extraction business (sec. 110004).

- Division S of the House bill, the Ocean Shipping Reform Act that has already passed the House several times.

- Section 2507 of the Senate amendment, a provision to allow a number of Cabinet Secretaries and agency heads (including the Secretary of Transportation) to fund the continuation of research projects that were interrupted by COVID.

- Section 4114 of the Senate amendment, a Buy America provision that is now obsolete (see below).

- Section 4116 of the Senate amendment, a Buy America provision that is now obsolete (see below).

Regarding those last two Senate provisions, the Senate first passed their bill on June 8, 2021. After that, the Buy America provisions that had been included in the competition bill were then lifted, almost without change, and plopped down into the bipartisan infrastructure bill.

But the House took what seemed like forever to write its own bill and did not pass anything until February 2022. Since the House added a tariff bill (and what seems like 200 other bills) to the package, it had to use the House bill numbers, so Majority Leader Schumer had to take up the House-passed bill and then offer the Senate bill as a substitute amendment – even though the Senate bill contained things that had already been passed into law in other legislation like the infrastructure bill.

So, even though the repetitive Buy America language is technically within the scope of the conference, it is highly likely that the conferees will just drop it as moot in the current negotiations.

Ocean shipping reform, on the other hand, is going to pass Congress somehow this year, it is only a question of whether it goes on its own or hitches a ride on another must-pass bill. And, since there aren’t that many must-pass bills anymore, the competition bill may be the best path forward.