After canceling its scheduled May meeting, the California High Speed Rail Authority (CHSRA) Board of Directors met yesterday, but shelved the main item of scheduled business – adoption of a draft biennial business plan. News reports indicate that behind-the-scenes discussions to truncate the system and redistribute money elsewhere are underway.

The 2020 business plan would implement the new direction ordered by California Governor Gavin Newsom since taking office in January 2019. That plan would:

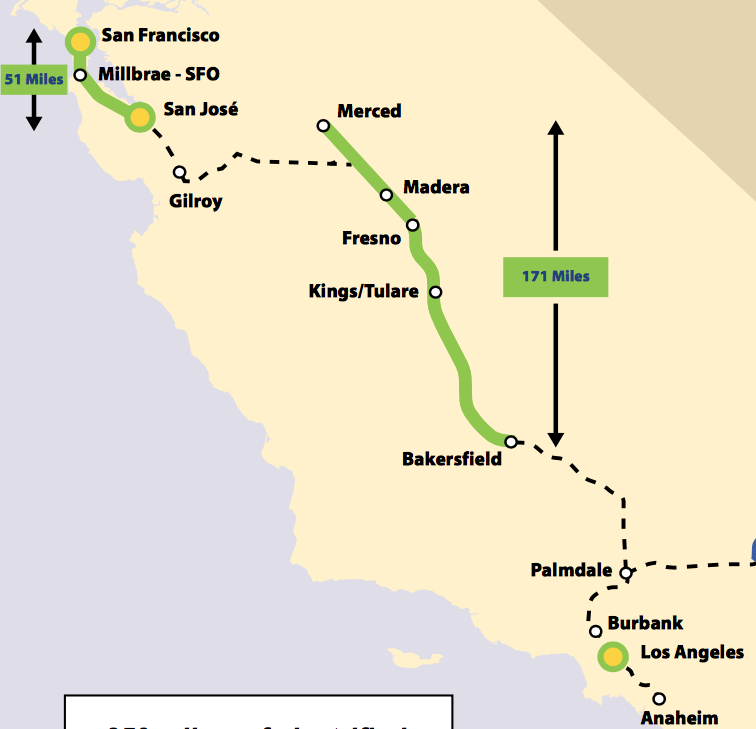

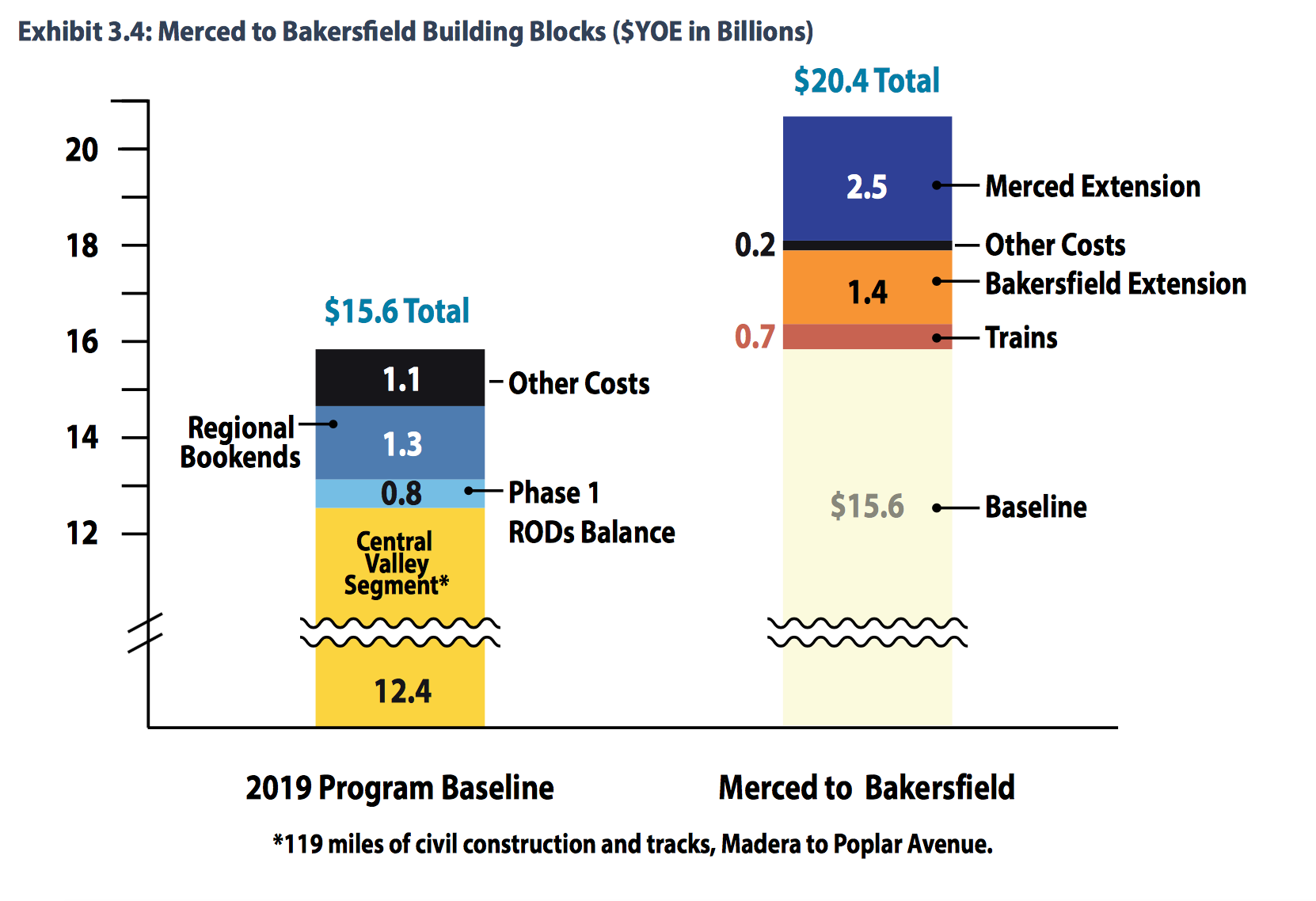

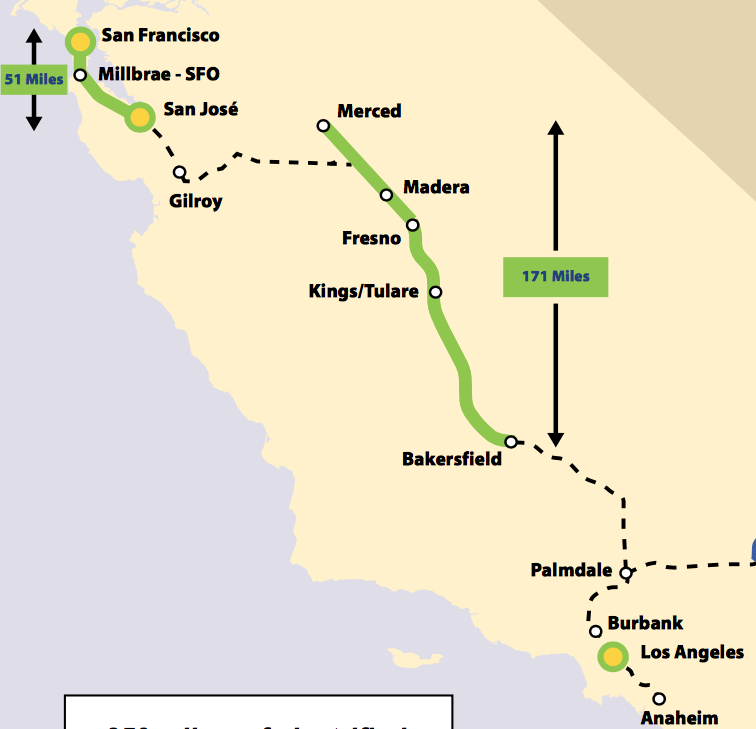

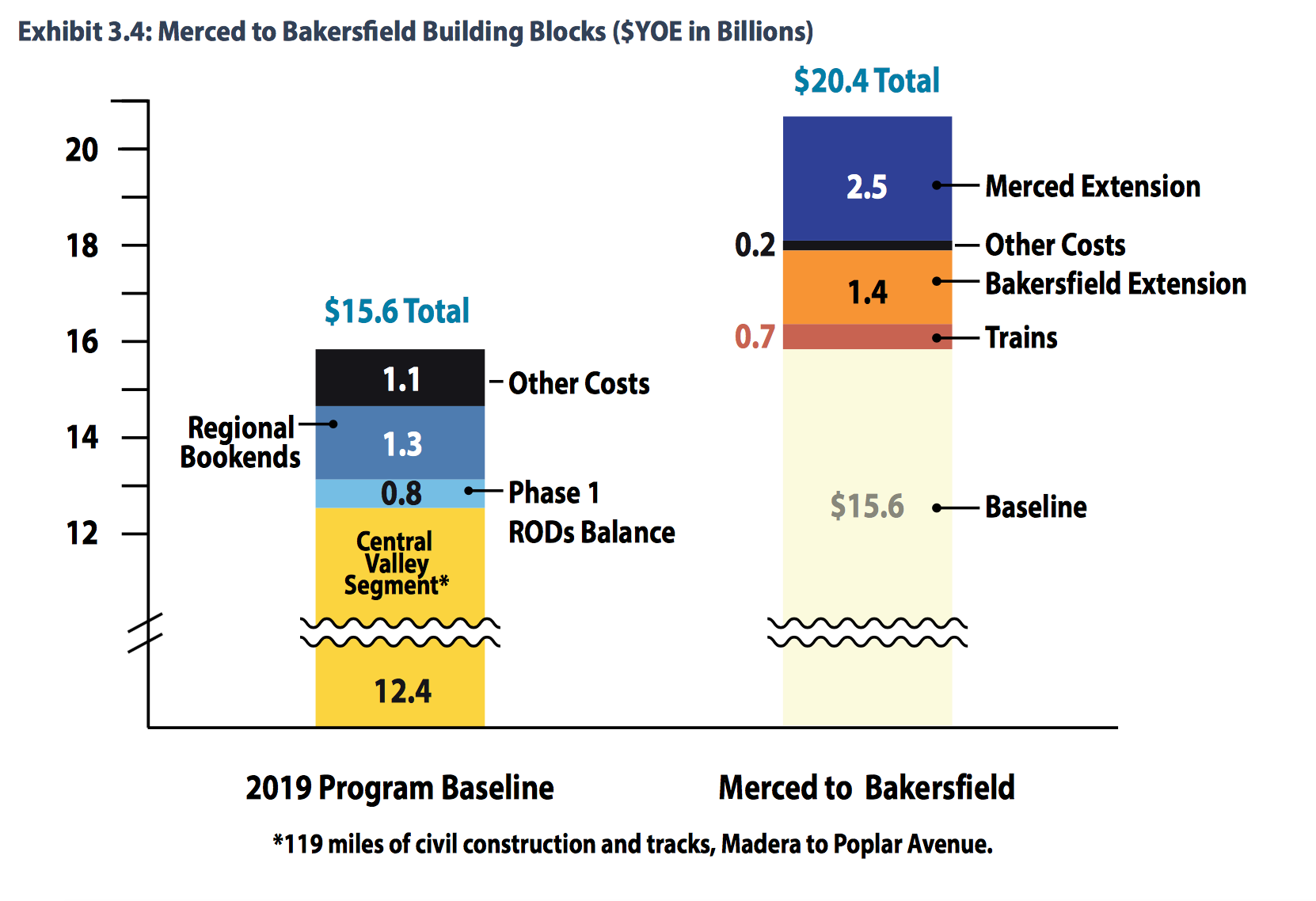

- Complete the ongoing construction of the 119-mile Central Valley Segment (track and catenary only – no trainsets) and three new stations from Madera to Shafter at a cost of $12.4 billion, and finish spending another $0.8 billion completing all the environmental impact statement paperwork for the whole proposed statewide system. (Both of those things are required under the terms of the federal grant agreements made in 2010, so if California does not complete those tasks, they have to repay the grant money they have already spent.)

- Spend another $1.4 billion to extend the line another 19 miles southwards from Shafter to a new station to be built in downtown Bakersfield.

- Spend another $2.5 billion to extend the line another 26 miles north from Madera to Merced and build a new station there.

- Spend $0.7 billion to buy six high-speed trainsets so that high-speed service can be offered from Merced to Bakersfield, starting in the year 2028.

- Finish spending $1.3 billion on regional “bookend” projects in the San Francisco and Los Angeles areas (including CHSRA’s contribution to the Caltrain Peninsula Electrification core capacity transit project) that has already been promised.

Together with another $1.3 billion in spending on things like a maintenance facility, the plan would spend a total of $20.4 billion, which is the entirety of the $9 billion in Proposition 1A bond proceeds approved by the electorate in 2008, plus the $3.5 billion in federal appropriations from fiscal years 2009 and 2010, plus the entirety of projected cap-and-trade revenues dedicated to CHSRA all the way through 2030.

Of the Prop 1A bond money, $4.2 billion remains to be appropriated by the state legislature. The draft business plan recommends disposing of the entirety of the money towards the plan discussed above: “This Draft 2020 Business Plan recommends the $4.2 billion in remaining available bond funds be directed to expand the 119-mile Central Valley Segment north and south to create an operating segment of 171 miles between Merced and Bakersfield, completing all Phase 1 environmental work from San Francisco to Los Angeles/Anaheim and completing all bookend project commitments using Proposition 1A funds.”

CHSRA anticipated letting a mammoth contract this fall to install all the track, electric catenary, and signalization in the 171-mile Merced to Bakersfield segment, before the legislature could appropriate the $4.2 billion.

This apparently pushed State Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon (D-Los Angeles) past his breaking point. In a remarkable move, Rendon and a bipartisan supermajority of the Assembly co-sponsored a resolution on June 3 (which passed by voice vote on June 11) telling CHSRA to call it off. H. Res. 97, co-sponsored by 67 of the 80 Assembly members, states that “the Assembly has the time to provide appropriate oversight and thoughtful consideration of all project alternatives without discussions and debate being prematurely stopped through actions by the High-Speed Rail Authority proposed to take place in the fall of 2020” and that “the High-Speed Rail Authority is hereby directed to not proceed with the execution of track and systems or train set procurements, or with the acquisition of the right-of-way along the City of Merced and the City of Bakersfield extensions, until the Assembly has considered and approved the High-Speed Rail Authority’s funding request for appropriation of the remaining bond funds.”

At the time the resolution was introduced, a joint statement from some of its sponsors was released, in which Speaker Rendon said “It is important to make sure that the High-Speed Rail Authority does not close the door to options other than the one created by a small handful of bureaucrats and the unelected Authority board. The voters have been given no voice since 2008 and their elected representative, the Legislature, has had no vote since 2012. Both of those votes were based on a much different high-speed rail project than the one under the proposed contract. That proposal would lock current legislators, and legislators for the next 15 sessions, into a no-changes situation. It’s time to pause and make sure that the plan to go forward works for 2020 and has the support of those of us elected to represent the people of California.”

H. Res. 97, being a one-chamber resolution, does not have the force of law, but it apparently had the political force necessary to force CHSRA to slow its roll, at least for now. But getting 67 of the 80 Assembly members on the same page is a rare enough thing that the Los Angeles Times reported two days ago that “Following the Assembly vote, the delay [in the CHSRA Board moving ahead] was decided in discussions between Rendon, Gov. Gavin Newsom and the rail authority board.”

Members of both the Assembly and the state Senate have become more vocal in recent years that they think using the remaining Prop 1A proceeds to improve commuter rail in the Los Angeles and San Francisco areas would be a much better use of the remaining funding than fording ahead with high-speed rail service in the much less populous Central Valley would be at this time. But diversion of the money away from the Central Valley greatly increases the chance that the 119-mile segment will become a “white elephant.” The LAT article (written by Ralph Vartabedian, who has done yeoman’s work on this story over the years) closes with a quote from an attorney for rail line opponents who speculates that a deal between Rendon, Newsom and the CHSRA board would divert the remainder of the Prop 1A funds to transit projects in L.A. and San Francisco, which then “would only fund the completion of 119 miles of track legally required under a federal grant agreement and then hand that system over for use by Amtrak.”

In which case a total of $12.4 billion would have been spent just so Amtrak diesel locomotives could go 30-40 miles an hour faster between Madera and Bakersfield.

Here are the current estimated populations of the metro areas that would eventually be served by the full Phase 1 rail plan, if California can ever find an additional $60 billion to build it:

| Metro Area (MSA) |

2019 Est. Pop. |

| San Francisco-Oakland |

4,731,803 |

| San Jose-Sunnyvale-Santa Clara |

1,990,660 |

| Merced |

277,680 |

| Madera |

157,327 |

| Fresno |

999,101 |

| Bakersfield |

900,202 |

| Los Angeles-Long Beach-Anaheim |

13,214,799 |

| Total, Phase 1 Service Area |

22,271,572 |

Per-mile cost. It should be noted that the capital cost of building the 119-mile Central Valley segment (sans trains) is currently budgeted at $104 million per mile. The extension to Merced might drag that per-mile cost down a bit, but those estimates aren’t as far along yet and may go up.

That’s the cheap part. The latest business plan shows the estimated cost of the missing link (see map below) in the north between Gilroy and just south of Merced to be $222 million per mile, because the preferred route would have 15.2 miles of tunnels and 16.1 miles of elevated viaduct in its 49-mile stretch. And in the south, the 79-mile Bakersfield to Palmdale segment would have an estimated per-mile cost of $207 million per mile (9.2 miles of tunnels, 16 miles of viaducts and bridges). And the 41-mile Palmdale to Burbank segment would have a per-mile cost of $428 million per mile (27.2 miles of tunnels under the San Gabriel mountains).