From a federal perspective, the key takeaway is this: the decision by the Obama Administration to dedicate use-it-or-lose-it ARRA stimulus money on a project that was not ready for construction, plus their highly unusual decision to allow a “tapered match” for the federal grants (whereby the state can spend 100 percent of the federal appropriation for a project jointly funded by the federal government and the state, with the state promising to pay its share later on, by a date certain) increasingly look like a bad idea. The report says:

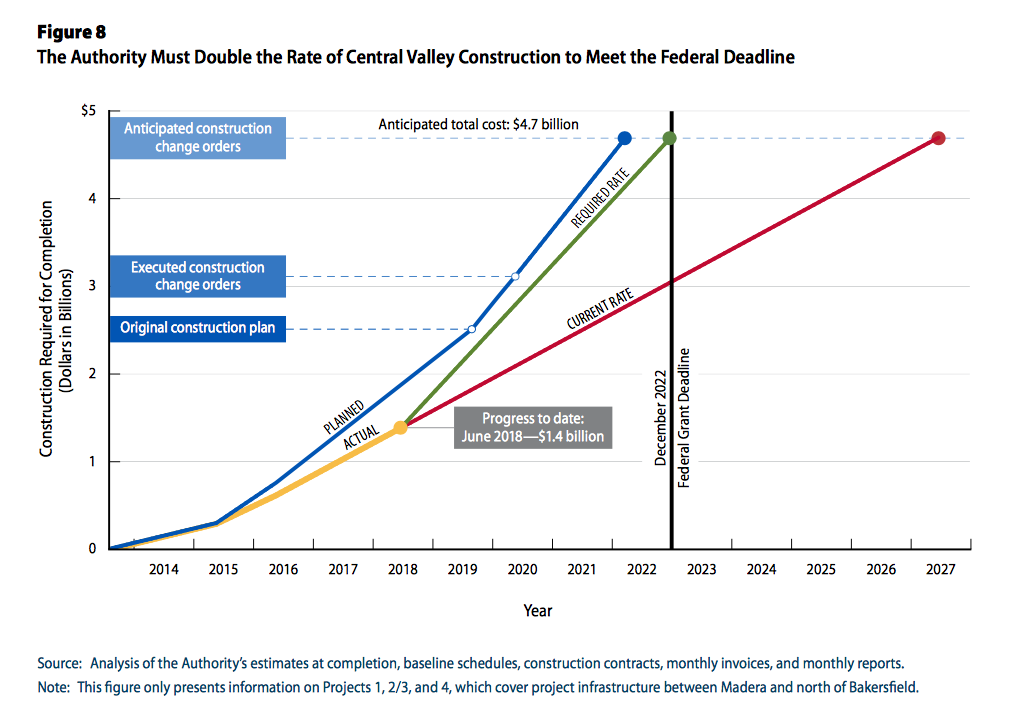

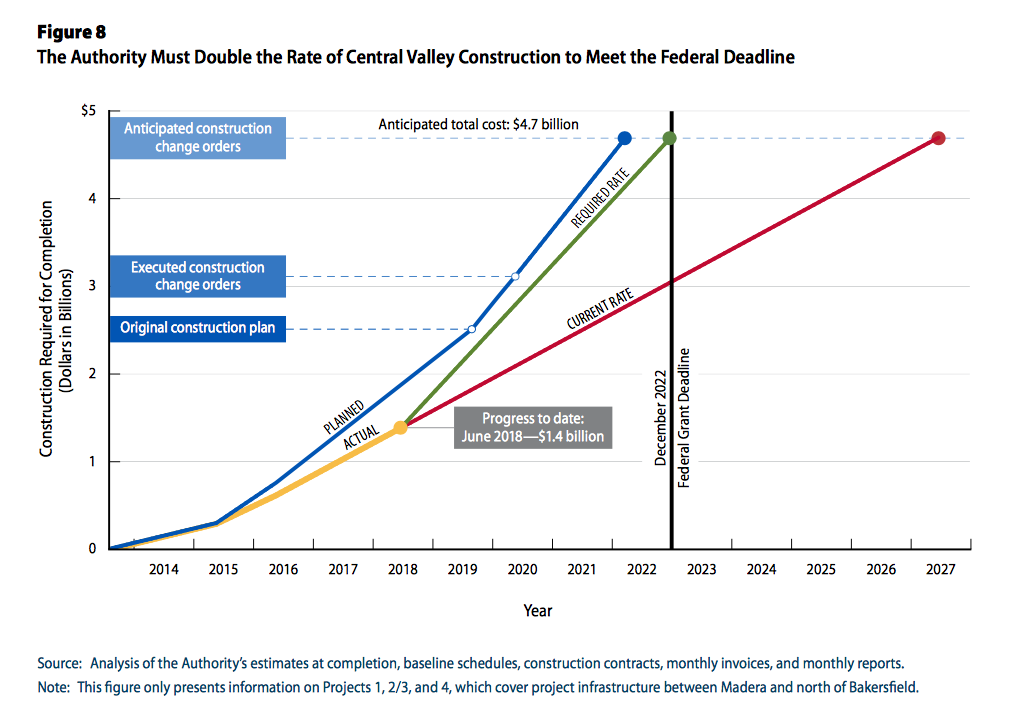

The Authority began construction in the Central Valley in October 2013 despite being aware of the risks associated with beginning construction early—the fact that the Authority had not acquired sufficient land for building, had not determined how it would relocate utility systems, and had not obtained agreements with external stakeholders. These unmitigated risks have contributed to $600 million in cost overruns thus far for the three active Central Valley construction projects, with another $1.6 billion in additional costs needed to complete the projects. The Authority has cited the terms of a 2010 federal grant—which originally required construction to be complete by 2017—as the primary factor in its decision to begin construction when it did. However, we determined that even with a grant deadline extension until December 2022, the Authority could miss the new deadline unless Central Valley construction progresses twice as fast as it has to date. Missing the deadline could expose the State to the risk of having to pay back as much as $3.5 billion in federal funds.

To put that $3.5 billion and the “tapered match” in perspective, here are the total federal grants for the Central Valley segment of the California high-speed rail project and their required state matching shares, from the funding agreements on the CHSRA website:

|

FRA Grant |

CHSRA Match |

Total |

| FY09 ARRA |

$ 2,552,556,231.00 |

$ 2,505,771,134.00 |

$ 5,058,327,365.00 |

|

50.46% |

49.54% |

|

| FY10 |

$ 928,620,000.00 |

$ 359,805,000.00 |

$ 1,288,425,000.00 |

|

72.07% |

27.93% |

|

| Total |

$ 3,481,176,231.00 |

$ 2,865,576,134.00 |

$ 6,346,752,365.00 |

|

54.85% |

45.15% |

|

Under a normal federal funding grant that is approximately 50-50 as the FY09 ARRA grant was, the state/local partner has to put up one dollar of cash for every dollar of federal money as it is being spent. For a standard 80-20 highway grant, the state DOT has to put up one dollar of cash for every four dollars of federal funding, as the money is being spent.

But the tapered match agreement meant that every single dollar of that $2.55 billion has already been spent (ARRA had a hard deadline of September 30, 2017 for every single dollar to be outlaid, lest if vanish in a puff of smoke). Almost none of the state match of $2.505 billion has been spent yet. (The FY10 money has no legal deadline for expenditure, and the CHSRA funding schedule indicates that they plan to spend the federal FY10 money last, starting in July 2020 and ending in June 2023 .)

As the auditor’s report notes, the original ARRA grant required the state share to be spent alongside the federal share and be complete by September 30, 2017. But the grant agreement was later amended in December 2012 to allow the tapered match and then amended again in May 2016 to extend the deadline for completion of the Central Valley segment to December 31, 2022. (See this May 2016 ETW article for more details.)

About that bit where the state may have to repay $3.5 billion if they can’t complete the Central Valley segment, as promised in the FRA funding agreements, by the end of 2022: this comes from a 2015 GAO letter stating:

If FRA determines the Authority has misused federal grant funds by, among other things, failing to make adequate progress on the project or otherwise failing to adhere to the terms of the Agreement, FRA may require the Authority to repay up to the entire amount of FRA funds paid under the Agreement. FRA also may seek repayment if the Authority fails to complete the project or one of its tasks under the Agreement, or if it fails to adhere to the [Funding Contribution Plan], or if FRA determines the Authority will be unable to meet its 50 percent share and complete the project on schedule. FRA can seek repayment either from the Authority or from the State of California because FRA’s repayment claim will constitute the collection of a claim of the U.S. Government under 31 U.S.C. Chapter 37, the basic statutory framework for collection of U.S. Government claims. Under this statute, FRA can recover its disbursements via an administrative offset against any funds payable by the U.S. Government to, or held by the U.S. Government for, the State of California.

(Emphasis added.)

This means that whoever is running the Federal Railroad Administration can simply refuse to amend the grant agreement further between now and December 2022 (there is a Presidential election intervening between now and then, of course) and potentially pick and choose $3.5 billion in other federal aid to California to cancel, if CHSRA can’t complete the Central Valley segment by that point. (The GAO letter does add the caveat that “It is uncertain whether the federal debt collection process has been used to recover funds of the magnitude potentially at issue under the Recovery Act Agreement.”)

Would FRA play hardball like that? Who knows.

Can California even finish the Central Valley segment by December 2022? This, also, is was questioned by the state auditor, and the answer appears to be: not at the rate they have been going. According to this chart in the auditor’s report, their current spending rates won’t finish the Central Valley segment until 2027:

And this is just talking about the Central Valley segment, which FRA and CHSRA picked in 2010 to start with because it was supposed to be the quickest, cheapest, easiest segment of the proposed system.

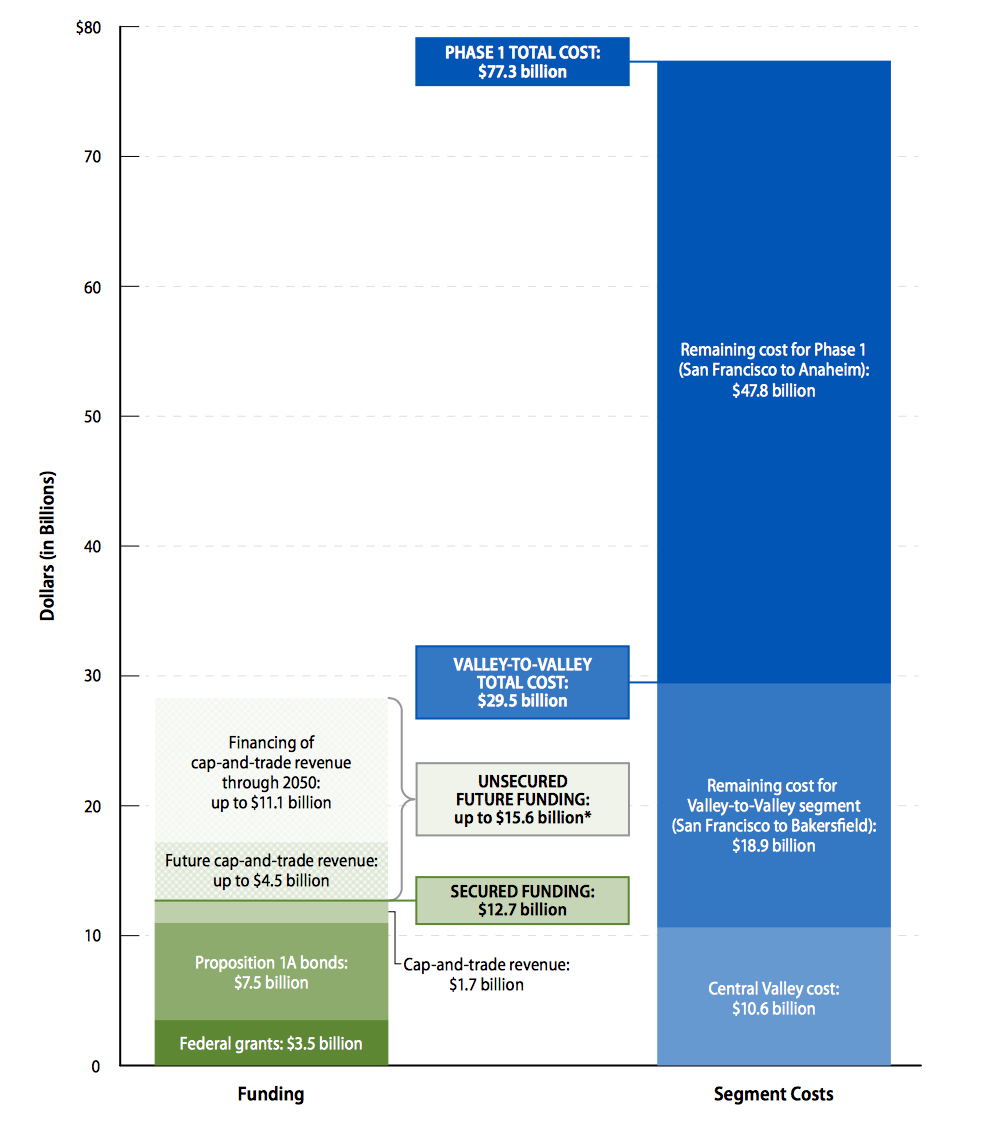

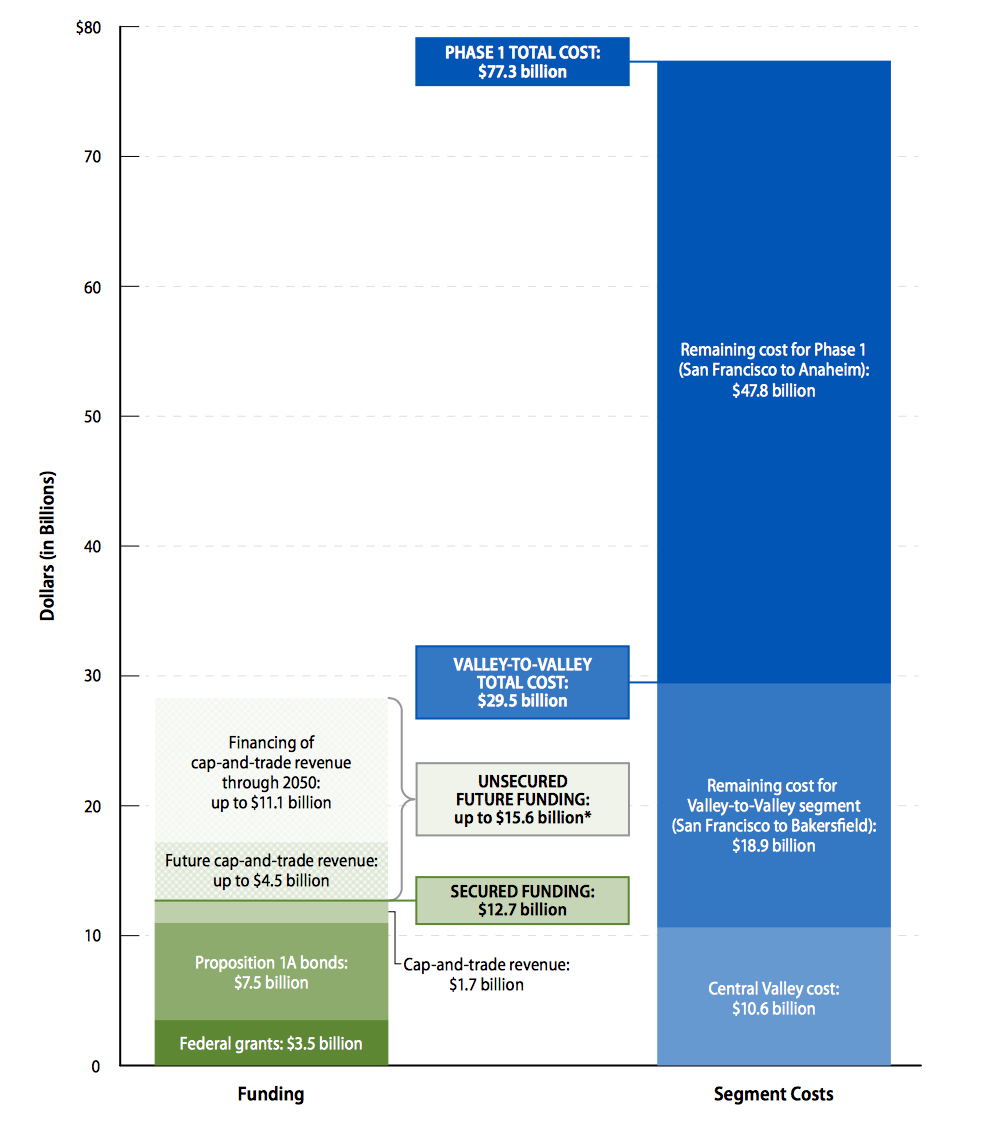

For the entire system, the auditor’s report also includes a good chart showing just how little money the state has actually identified to pay for the rest of the system: