The Joint Committee on Taxation this week issued its long-awaited budget score of the revenue provisions of the mammoth budget reconciliation bill. As part of this process, they estimated that the cost to the Treasury of the revised electric vehicle purchase tax credit of up to $12,500 per vehicle would total $9.2 billion over the next decade.

Under the language in the bill, the amount of the tax credit would vary, from a minimum of $4,000 to the maximum of $12,500 depending on whether the vehicle meets minimum battery size and maximum gasoline tank size requirements, was assembled in a union shop in the United States, and meets domestic battery content rules. In order to get a budget score, some JCT analyst must have used an internal assumption for the average tax credit, and we don’t know what that is.

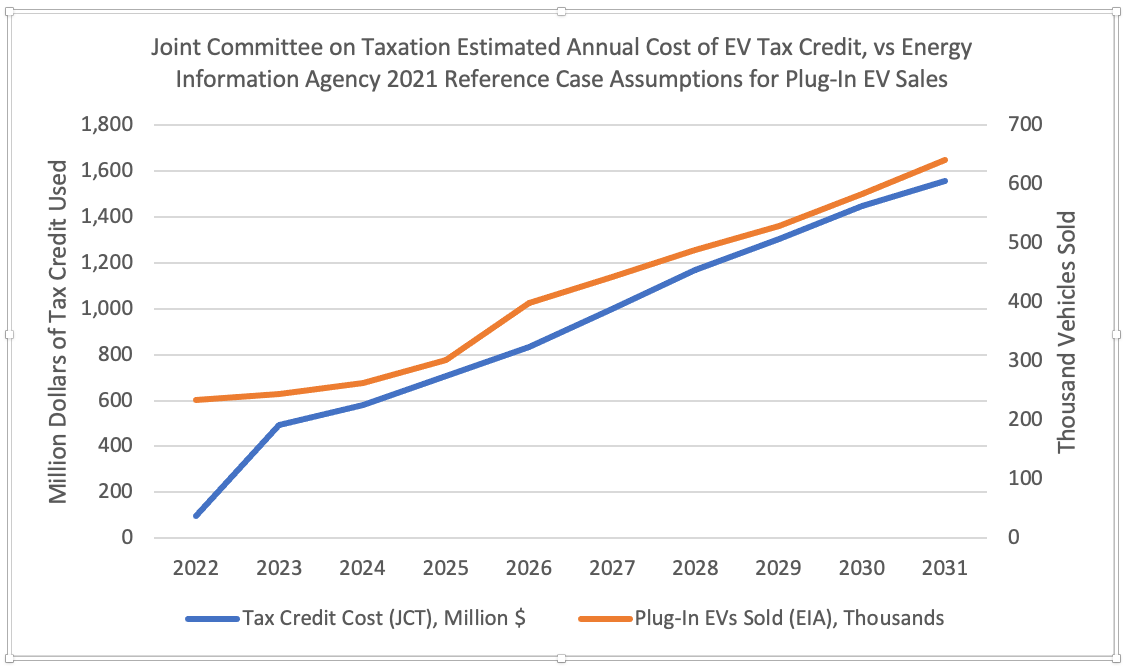

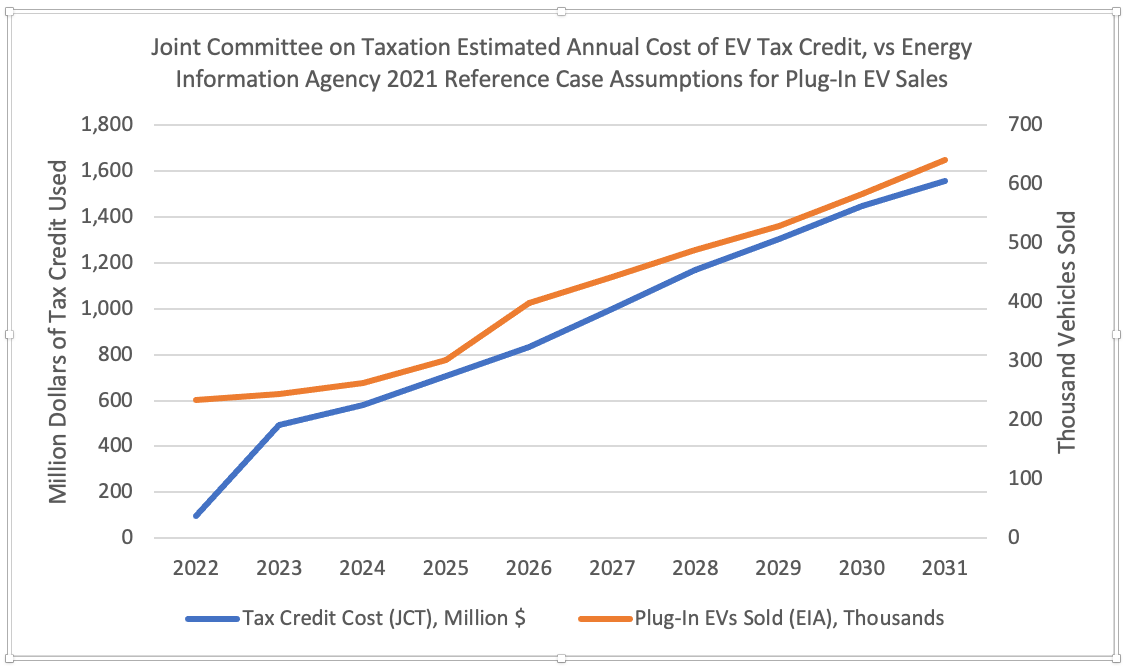

But we strongly suspect that JCT used the Energy Department’s 2021 “reference case” assumptions for plug-in electric vehicle assumptions over the next decade, which are very conservative and only assume a total of 4.1 million plug-in EVs being sold over the next decade. Not only do JCT and the Congressional Budget Office use the reference case for motor fuel sales when forecasting fuel excise tax receipts, we can tell the reference case is being used in this instance because the shapes of the lines are almost identical when you graph them out – in the chart below, the blue line is the annual tax credit cost from the JCT score, in millions of dollars per year, measured against the left axis, and the orange line is the number of plug-in electric vehicles and qualifying plug-in hybrids assumed to be sold in the U.S. each year under the EIA reference case, in thousands of vehicles and measured against the right axis. (Left axis are fiscal years and right axis are calendar years, but there’s no way to fix that with the available data.)

This is an assumption of slow but steady growth in EV sales, both in absolute terms and as a share of total light duty vehicle sales, which the EIA reference case estimates to stay relatively flat in the future. When you focus only on the types of vehicles that the Administration is trying to promote (pure plug-in EVs, fuel cell vehicles, and plug-in hybrids that only have de minimis gas tanks to run a generator to charge the battery on long trips), the EIA reference case assumes that those sales will almost triple over a decade, from 1.6 percent of the market in 2022 to 4.3 percent of total sales in 2031.

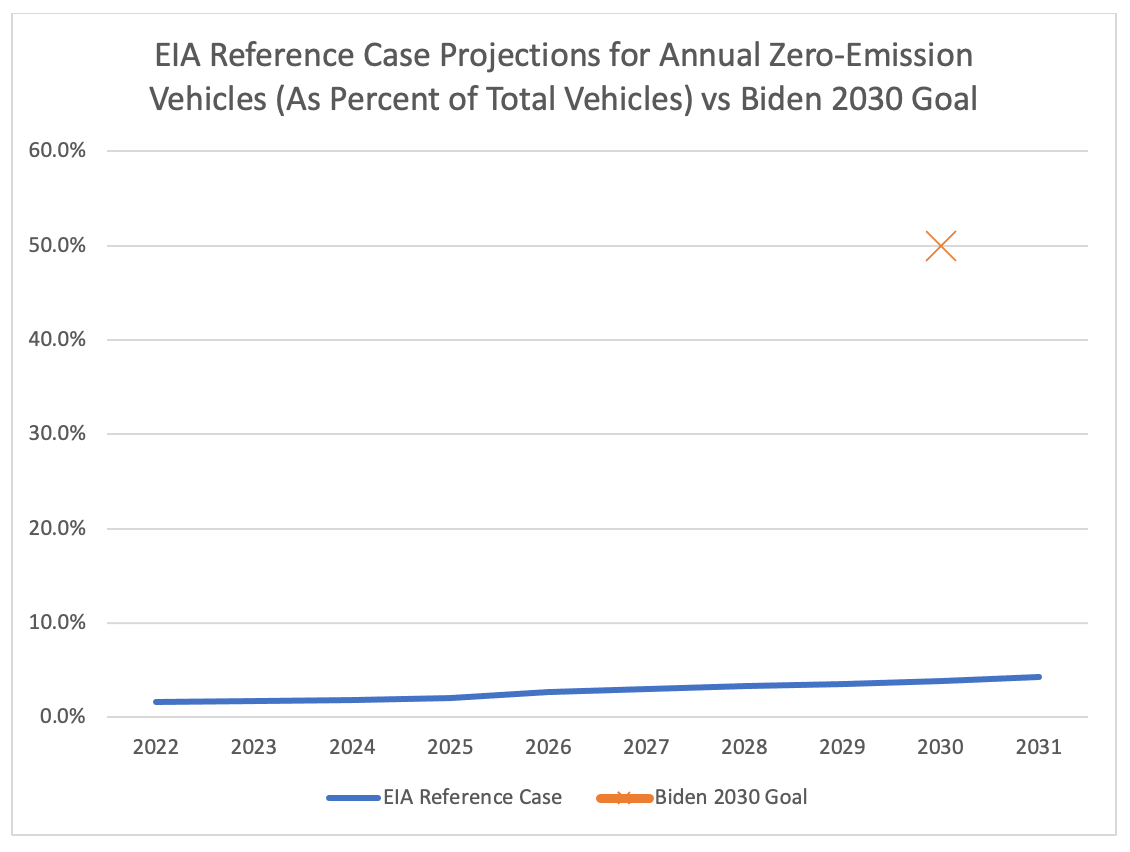

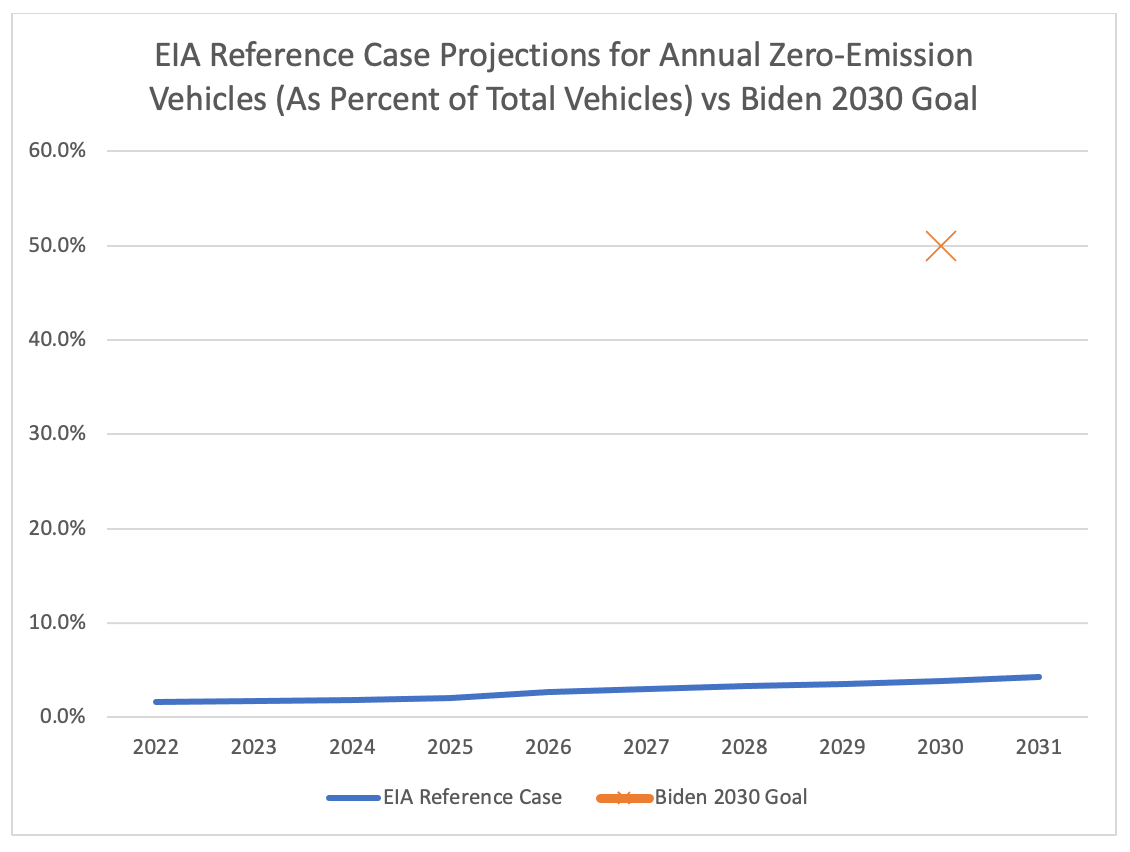

However, this steady rate of increase is a far cry from what the Biden Administration wants, as expressed in Executive Order 14037, signed on August 5, 2021. EO 14037 expressed a (non-binding) policy of “setting a goal that 50 percent of all new passenger cars and light trucks sold in 2030 be zero-emission vehicles, including battery electric, plug-in hybrid electric, or fuel cell electric vehicles.” Biden signed the order after a public White House meeting with the heads of what is left of the Big Three domestic automakers, who expressed aspirational goals to hit that target.

The difference between the EIA reference case of slow-but-steady growth in ZEV sales (as a percent of total sales) and the Biden 2030 goal is best shown visually:

Obviously, the ZEV sales assumptions in the EIA reference case exist in a different universe than the one that President Biden wants us to live in. And the EIA reference case was locked and released before the (Biden-urged) Big Three pivot to EVs that has occurred this year.

The bottom line: if the tax credit is enacted, and if plug-in EV sales in the real world come anywhere close to the aspirational target set by President Biden, then the cost of the tax credit to the Treasury will be far in excess of $9.2 billion – perhaps closer to the $100 billion originally proposed by the White House for EV point-of-sale rebates in its original American Jobs Plan almost nine months ago.