Yesterday, the American Public Transportation Association asked Congress to appropriate an additional $23.8 billion in coronavirus-related relief to mass transit providers across the country, in addition to the $25.0 billion provided in March 2020 by the CARES Act.

“The $25 billion that was provided by the CARES Act was a lifesaver for public transit services but we now have a more complete picture of the extraordinary and devastating impact,” said APTA President & CEO Paul P. Skoutelas. “These additional funds are critical to continue serving essential workers and make sure that we can help get our country back to work and to other activities that are so important for our economic recovery.”

The CARES Act was thrown together in a hurry. The coronavirus crisis developed so quickly that APTA originally asked Congress for $12.875 billion on March 17 ($2 billion for direct costs like extra cleaning of railcars and buses, and $10.875 billion for a very rough estimate of lost dedicated fare and tax revenue), and then quickly upped their request to $16 billion on March 19. By March 22, the Senate had publicly proposed $20 billion for transit, and the House then pushed back and got the total up to $25 billion by late on March 24.

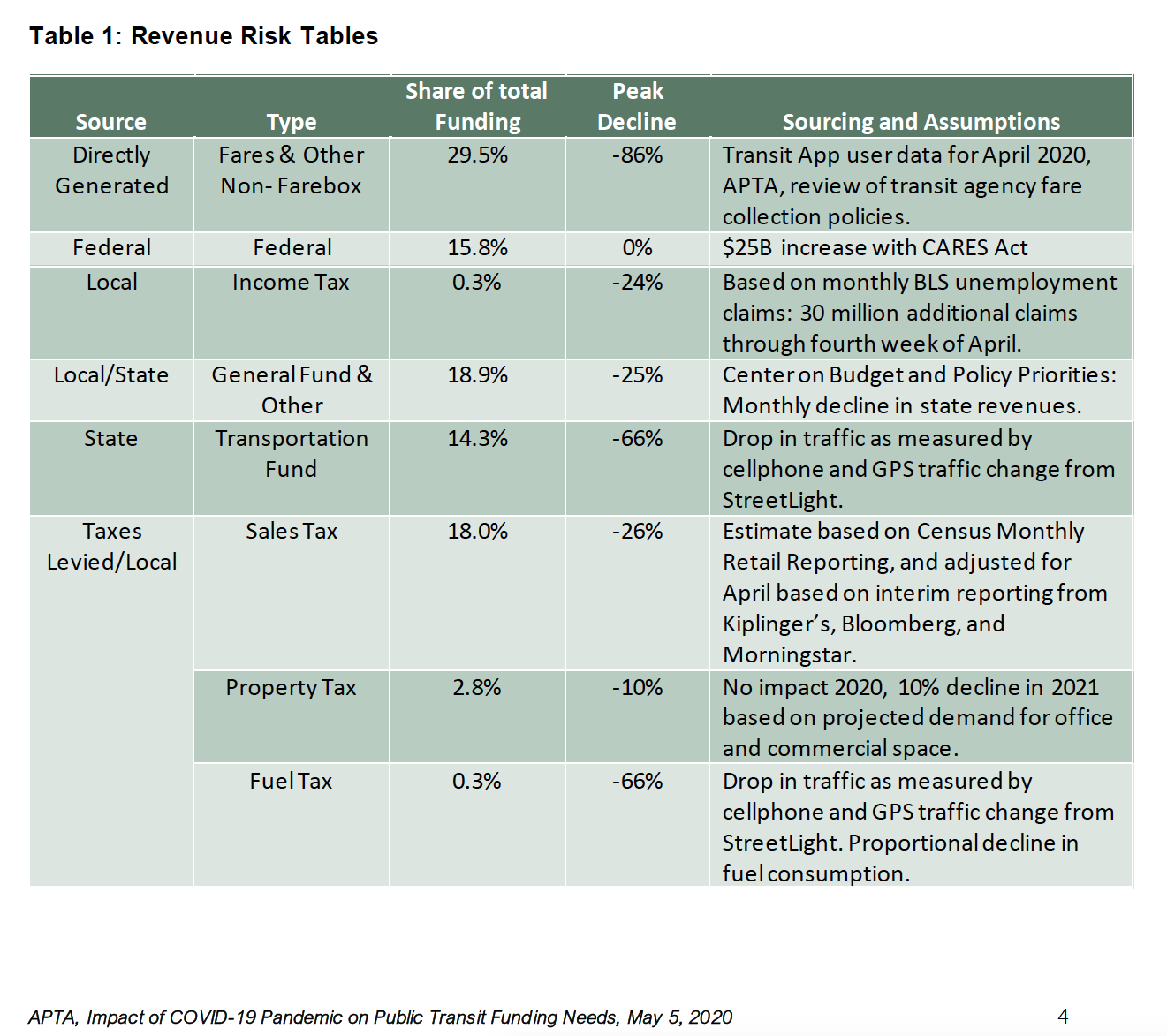

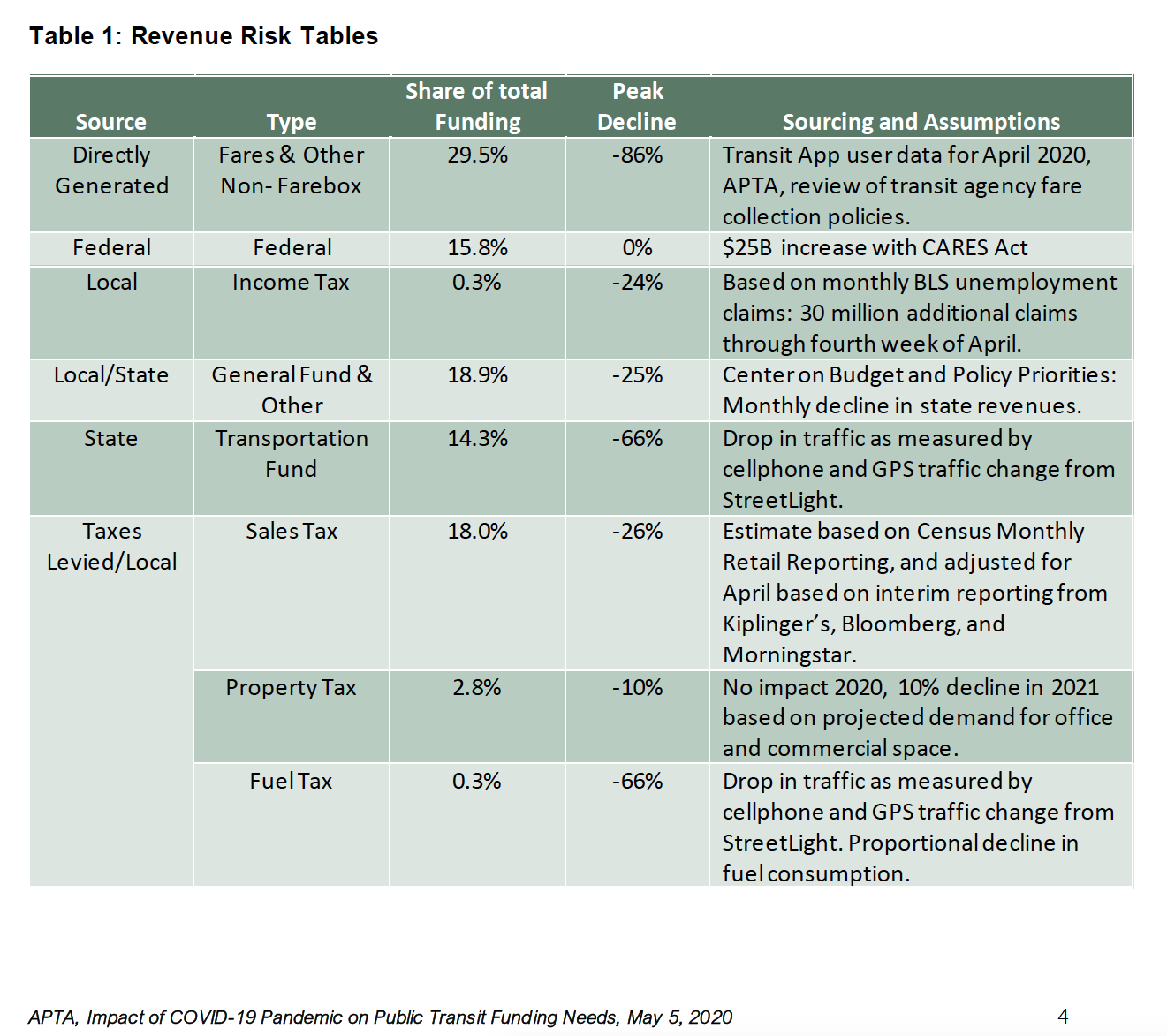

This time, APTA has had time to consult with an international economic research firm (EBP) and come up with a more detailed estimate of transit funding needs to respond to coronavirus. In particular, the EPB study for APTA is the first real attempt we have seen to break down the different types of revenues raised by transit agencies and sort them out by how much coronavirus is reducing individual revenue streams:

The report concludes “Cumulatively, declines in all of these sources translate to projected transit increased costs and revenue losses of over $26 billion in 2020 (including Q1) and over $24 billion in 2021. Even after accounting for the $25 billion in transit funding provided by the CARES Act, transit agencies’ net revenue gap through the end of CY 2021 is still projected to be $23.8 billion (between CY 2020 Q2 and CY 2021 Q4).”

(Separately, the report also warns that “Revenue declines will also have impacts on transit capital project development and construction. It is estimated that transit agencies nationally will likely need to decrease capital spending by $8.4 billion in 2020 and $7.8 billion in 2021. Moreover, the cost of capital spending is increasing because credit rating agencies have downgraded public transit agencies’ revenue bond ratings…Reduced capital spending may also delay some of the largest transit investments in the nation. Several major transit agencies have identified $17 billion of capital projects slated for implementation starting in 2020 that are now at risk of delay or cancellation.”)

If that’s the size of the ask, how does APTA propose to distribute that money to transit agencies?

APTA (and Congress) have sometimes had a hard time balancing the needs of big cities, particularly rail-intensive big cities, with the needs of the much more numerous smaller cities and rural areas, because their needs are so different, and because the total amount of funding available is always constrained, forcing hard decisions. The way the transit funding in the CARES Act was developed reflected that. The original Senate bill proposed $20 billion, 80 percent of which was to go out under the §5307 urbanized area formula, and 20 percent of which was to go out under the §5311 non-urbanized area formula. But the definition of “urbanized area” under §5307 is any area with more than 50,000 people (see the formula here), and the way the money is distributed, about 30 percent of the urbanized formula money goes to areas with populations under $1 million.The five largest transit areas (New York City, Los Angeles, Chicago, the D.C. area, and Philadelphia) collectively only got about 35 percent of total §5307 funding in 2020 under that formula.

After pushback from the House of Representatives (and Senate Democrats), the final CARES Act provided $25 billion, and the §5337 State of Good Repair formula was thrown into the calculation as well. This formula predominantly benefits the big legacy systems (the five biggest recipients under that formula got 55 percent of that program in the regular 2020 apportionments). In the final CARES Act, 55 percent of the money went out via the §5307 urbanized area formula, 30 percent went out under the §5337 state of good repair formula, and only 8 percent went out under the rural formula. (Another 7 percent went out under a Senate formula tweak designed to “plus up”fast-growth and high-density states.)

In their detailed proposal this time, APTA only proposes to put out another $4.75 billion through transit formulas – $4.0 billion through the urbanized area formula, $522 million through the rural formula, and $232 million through the elderly and disabled transit formula.

The remainder of the money – $19.0 billion – would not go out via a predetermined formula – but it wouldn’t be quite discretionary, either.

APTA is proposing that Congress appropriate the money under the transit emergency relief program in 49 U.S.C. §5324 (which is normally distributed, when appropriated, at the Secretary’s discretion), and orders the Secretary to distribute the money in three equal tranches of $6.333 billion over the next 20 months, as follows:

…the Secretary shall provide grants to designated recipients for such costs and revenue losses that exceed public transportation funding provided to such recipients by section 5307, section 5310, and section 5311 apportionments under the CARES Act (P.L. 116-136) or this heading of this Act, or reimbursed by the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act: Provided further, That the Secretary shall distribute allocations proportionally to all designated recipients that, based on best available data, demonstrate such costs and revenue losses in three tranches occurring not later than June 30, 2020, May 31, 2021, and December 31, 2021: Provided further, That the Secretary shall allocate not less than 33.33 percent of available funds in each of the three tranches and allocate any unused funds to subsequent tranches…

Essentially, every transit agency in America would write to the Secretary and ask for however much money they think they need to cover coronavirus-related costs or replace revenues lost to coronavirus, and then the Secretary adds up those requests, and if they exceed $6.333 billion, the Secretary will reduce every request by the same pro rata percentage to fit under the $6.333 billion cap. (The language is a bit weird – it says that each tranche shall be “not less than” $6.333 billion, but if you make the first or second tranche more than than that amount, you run the risk of not having enough money to make the third tranche “not less than” $6.333 billion, which is verboten, so we are assuming three equal tranches.)

This obviously gives every transit agency a financial incentive to ask for as much money as possible, in the hopes that their share of a $6.333 billion tranche of aid will be a smidgen higher. The proposed bill language charges the Secretary with analyzing each agency’s request and determining whether or not the agency has adequately demonstrated the need for all of the money, or just some of the money. Out of the $50 million in administrative expenses set aside off the top of the total proposed appropriation, $3 million is to be transferred to the DOT Inspector General to “support oversight of the Federal Transit Administration’s administration of the Emergency Relief program and its determinations of demonstrated need under this heading…”

So, the Secretary would have the discretion to determine whether an individual transit agency has actually demonstrated that it needs and deserves all or some of the money it is asking for, but once the Secretary accepts that demonstrated need, the Secretary would no longer have funding discretion and would have to give that agency a proportionate share of funding available in that tranche. Not truly discretionary, but not formula-based, either.

(It’s not clear if that is a responsibility that the Secretary would want.)

Both the $19 billion in emergency relief money and the $4.75 billion in formula money would be subject to the following bill language:

…notwithstanding subsections (a)(1) or (b) of section 5307 of title 49, United States Code, or any other provision of law, funds provided under this heading are available for operating and capital expenses of public transit agencies, including reimbursement for operating costs to maintain service and lost revenue due to the COVID-19 public health emergency, the purchase of personal protective equipment, and paying the administrative leave of operations personnel due to reductions in service: Provided further, That such operating expenses are not required to be included in a transportation improvement program, long-range transportation, statewide transportation plan, or a statewide transportation improvement program: Provided further, That the Secretary shall not waive the requirements of section 5333 of title 49, United States Code, for funds appropriated under this heading in this Act: Provided further, That unless otherwise specified, applicable requirements under chapter 53 of title 49, United States Code, shall apply to funding made available under this heading in this Act, except that the Federal share of costs for which any grant is made under this heading in this Act shall be, at the option of the recipient, up to 100 percent…

House Democratic leaders may unveil their draft of a fifth coronavirus response bill as soon as next week, but that bill is expected to be an (optimistic) starting point for negotiations with the Senate and the President, not a pre-negotiated finished project like the earlier bills.