What a difference two years makes.

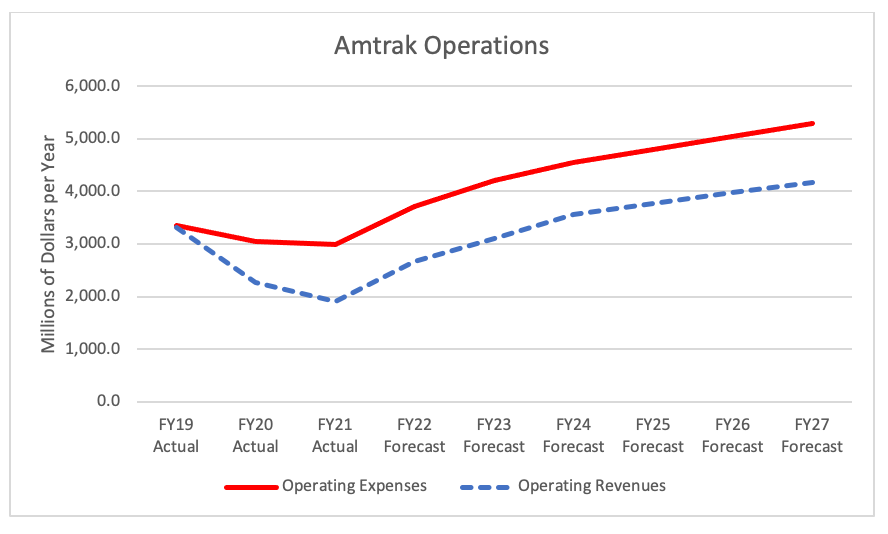

In fiscal 2019, Amtrak only lost $29 million on operations, and the budget estimates submitted to Congress in March 2020 predicted a break-even that year, followed by small but steady operating profits through 2025. The very profitable Acela service and the less profitable regional service between D.C. and Boston had finally pulled in enough operating revenues to pay for the losses of the long-distance trains, as was originally envisioned back in 1970. By 2023, the unified operating profit would reach $35 million, and that would double two years later.

It didn’t turn out that way, of course. Former CEO William Flynn told Congress in September 2020 that “Amtrak was on track to generate passenger revenues exceeding operating expenses in FY 2020 for the first time ever…Unfortunately, the COVID-19 pandemic then hit this nation. Amtrak, like all transportation providers, was hit especially hard. In a matter of weeks, Amtrak’s ridership plummeted by 97% and we undertook immediate actions to protect the health and safety of our customers and employees and reduce capacity.”

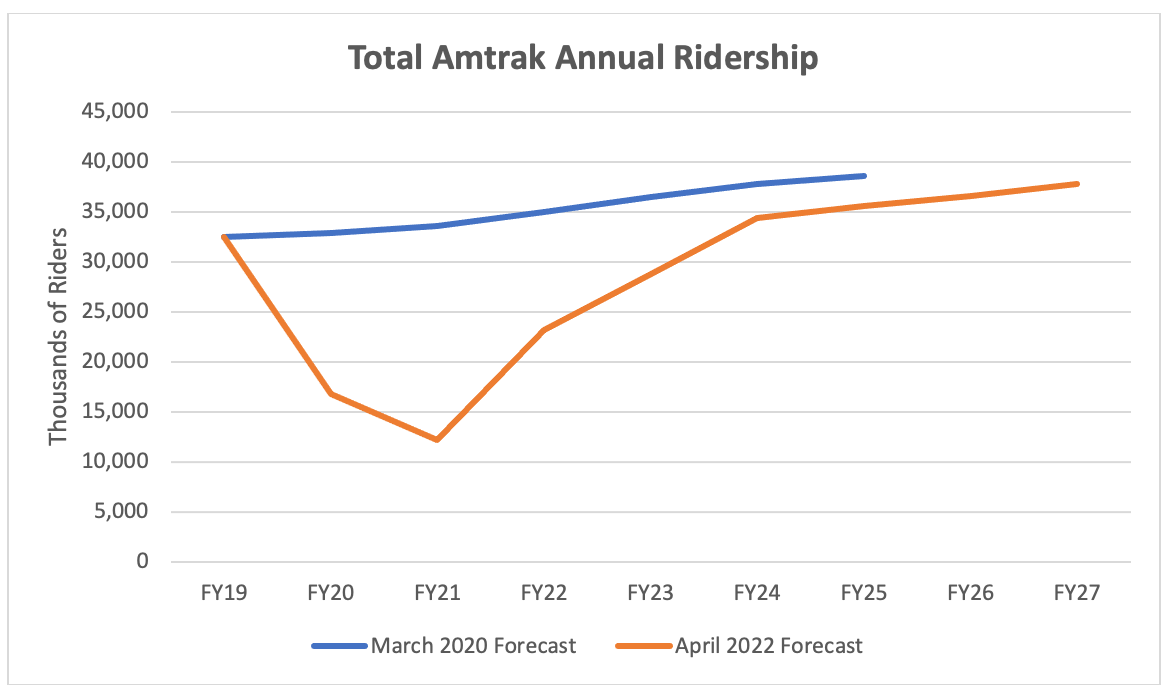

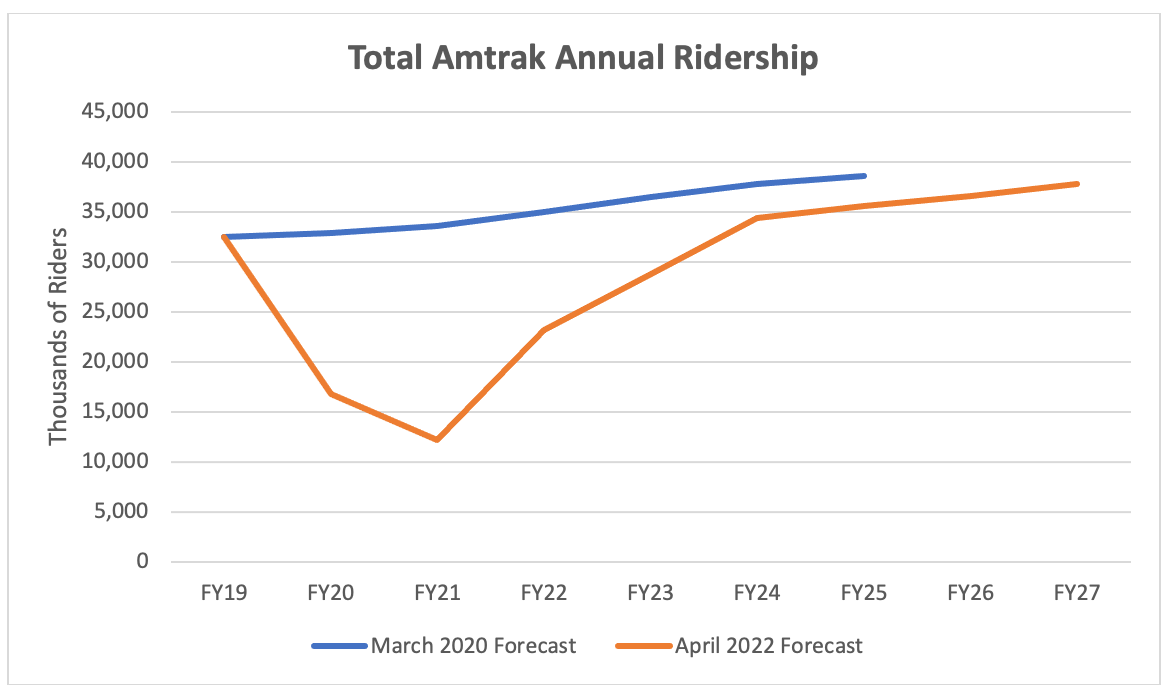

The combined operating loss for the railroad went from $29 million in the pre-COVID FY 2019 to $789 million in the half-COVID FY 2020 to $1.08 billion in the completely-COVID-but-getting-vaxxed FY 2021. Those losses have been covered by $3.7 billion in emergency COVID funding provided by Congress in fiscal years 2020 and 2021. But ridership is now returning – Amtrak’s new projections estimate that ridership will return to pre-COVID levels, just a couple of years behind schedule:

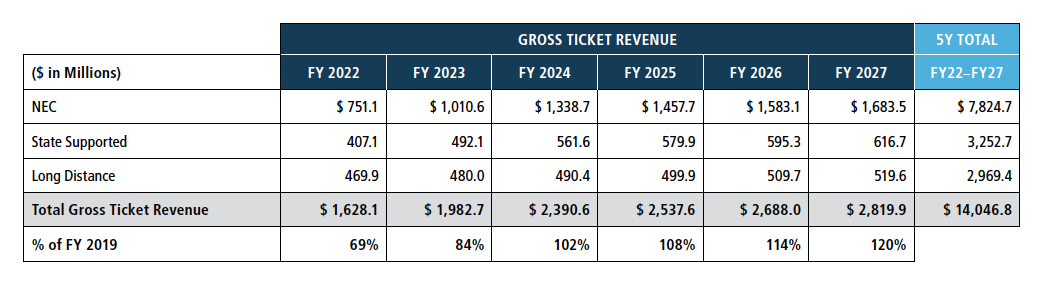

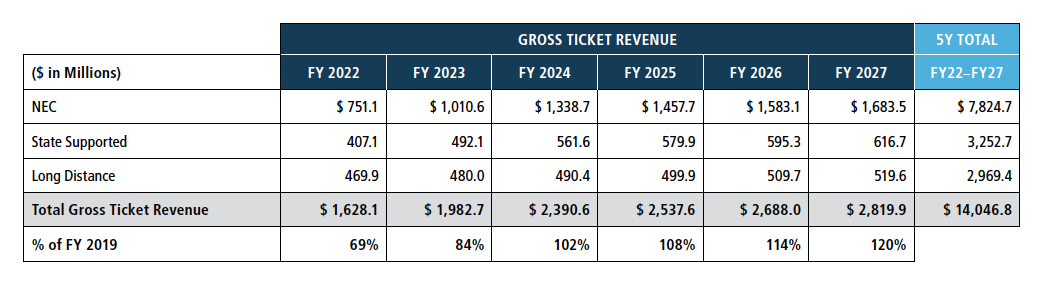

And, with ridership comes ticket revenues. Amtrak now predicts that gross ticket revenue will be back to the pre-COVID annual level by FY 2024:

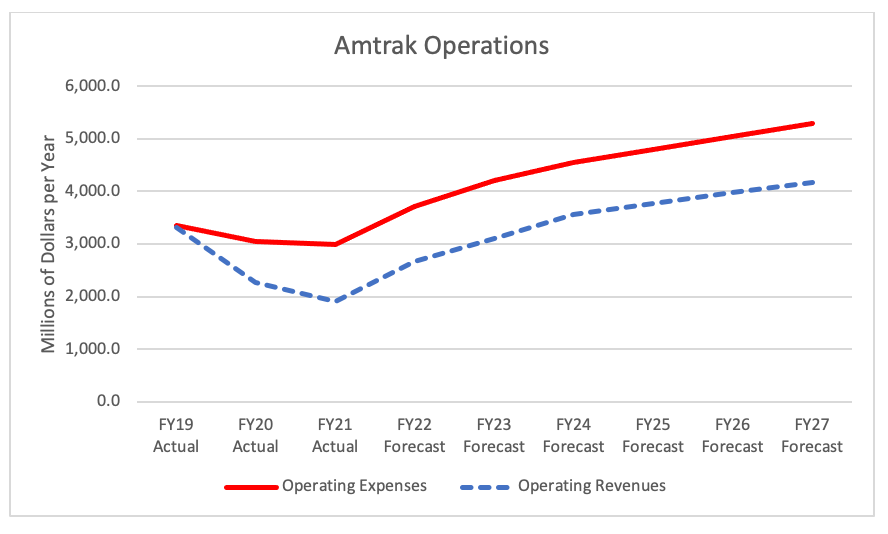

Yet, despite ridership and revenue returning to pre-COVID levels, Amtrak has apparently decided to give up on ever getting back to the pre-COVID position of an operational break-even. The new budget assumes $1 billion per year combined operational losses, in perpetuity.

In terms of recovery ratio (operating expenses divided by operating revenues), systemwide, Amtrak was at 99 percent in FY 2019, and then dropped to 74 percent in 2020 and 64 percent in 2021. The new budget plan calls for this ratio to get back to 72 percent in the ongoing FY 2022 and then rise back to 74 percent in 2023, but then it will stall at 78 percent in 2024 and at 79 percent in each of fiscal years 2025-2027.

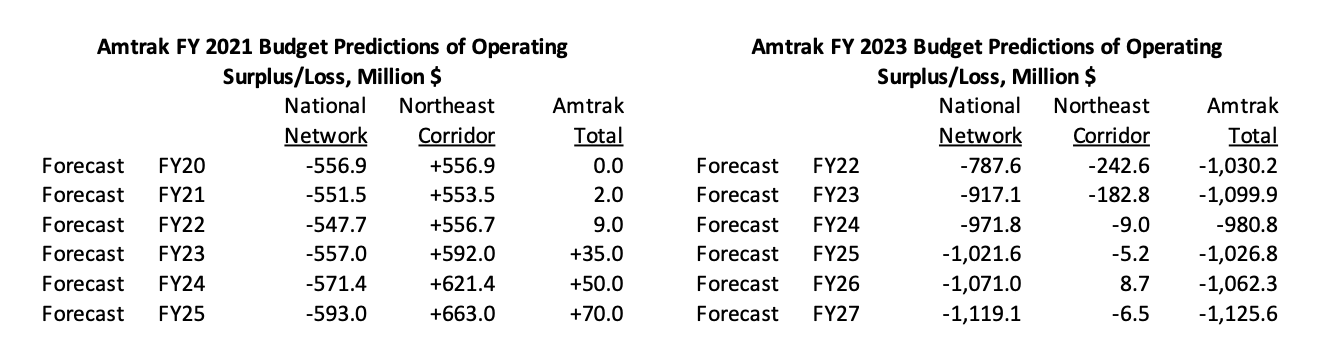

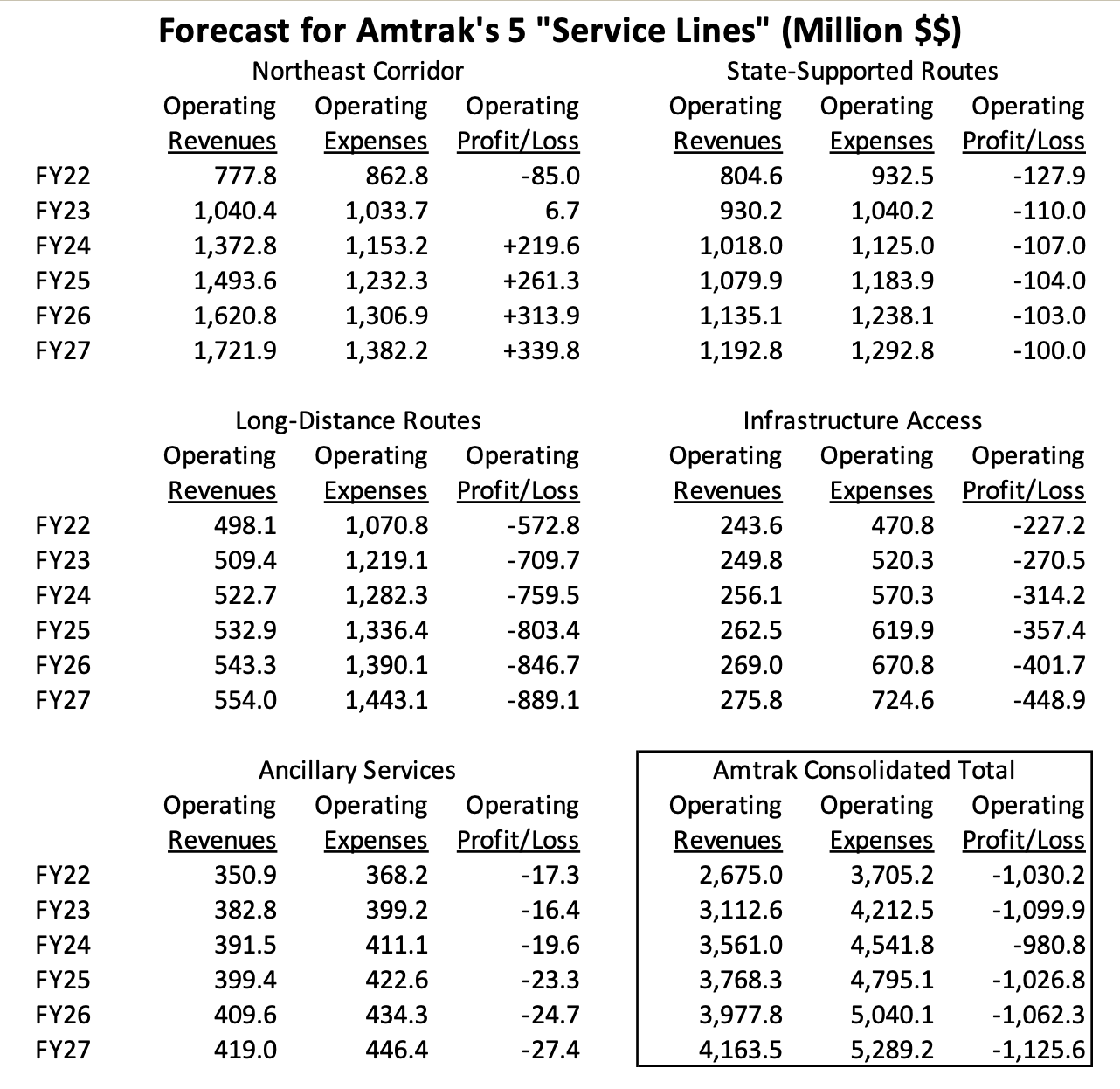

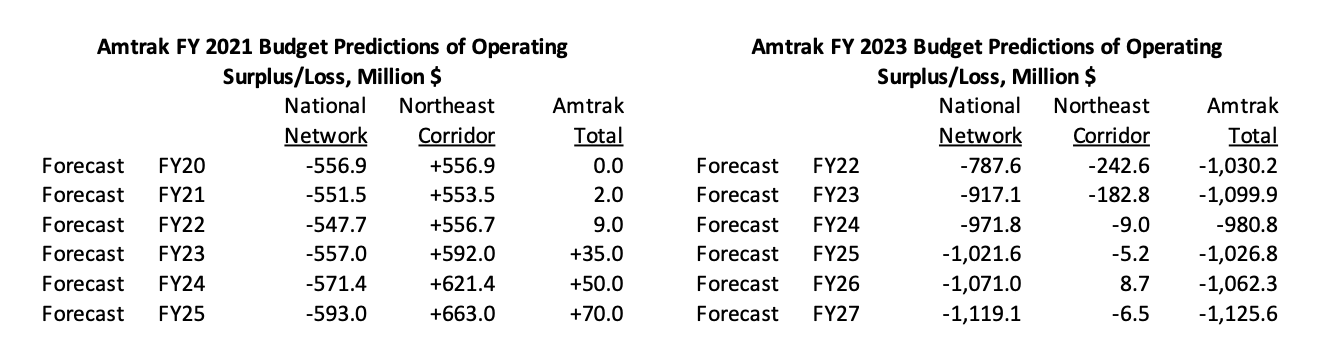

The assumptions of increased operating losses are split fairly evenly between the Northeast Corridor budget account and the National Network budget account:

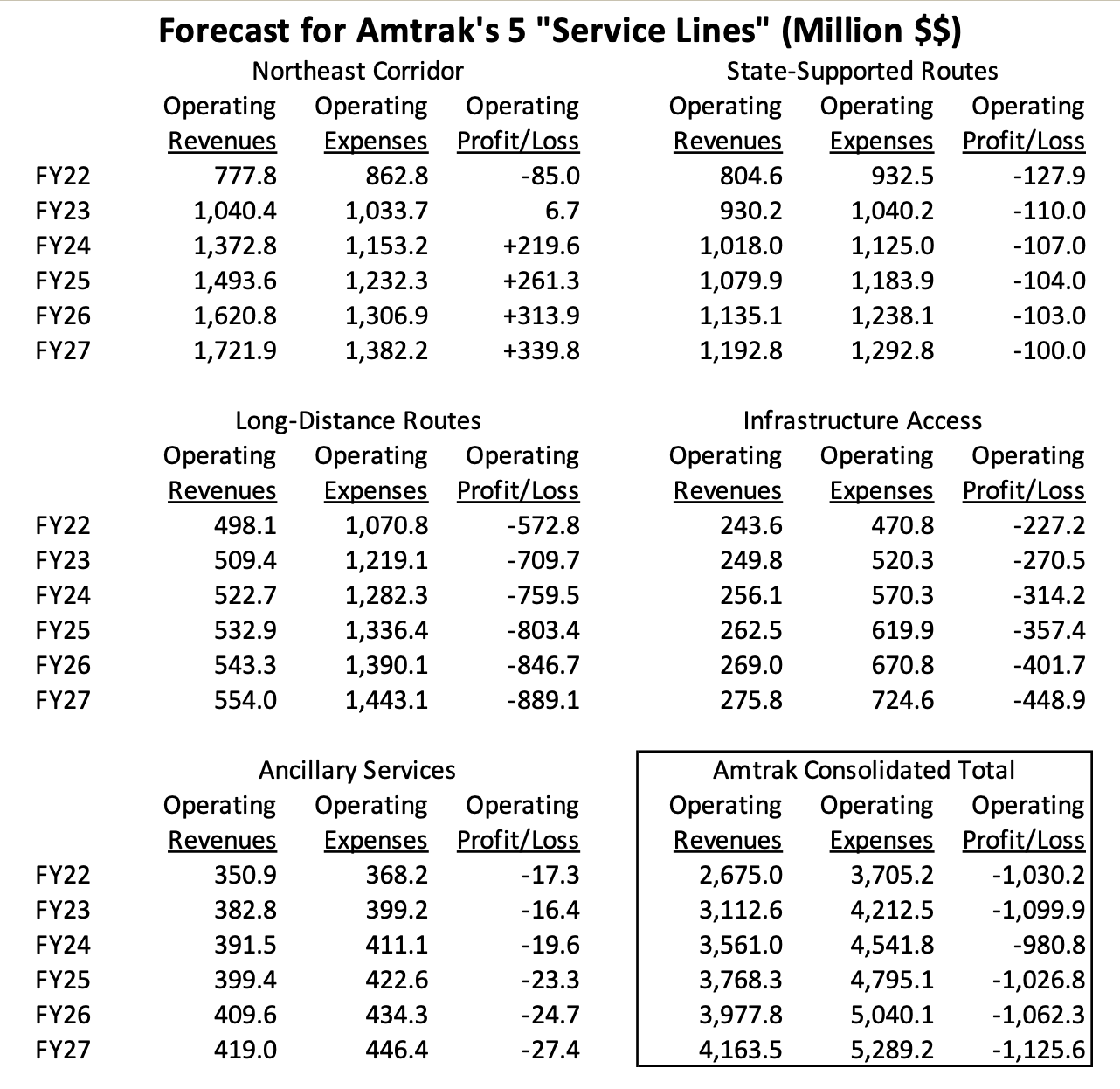

A better way to look at Amtrak is not by the two budget accounts, but by the five “service lines” – the Northeast Corridor, the state-supported routes under 750 miles, the long-distance trains, “infrastructure access” (sharing the NEC infrastructure with commuter railroads), and ancillary services.

In terms of operating ratio, the Northeast Corridor was traditionally a cash cow. The NEC-only cost recovery ratio was 170 percent in FY 2019. A brief discussion in the back of Amtrak’s budget request says that the NEC cost recovery ratio bottomed out at 53 percent in FY 2021, will get back to 90 percent in FY 2022 – but, five years later, will only be at 123 percent in 2027.

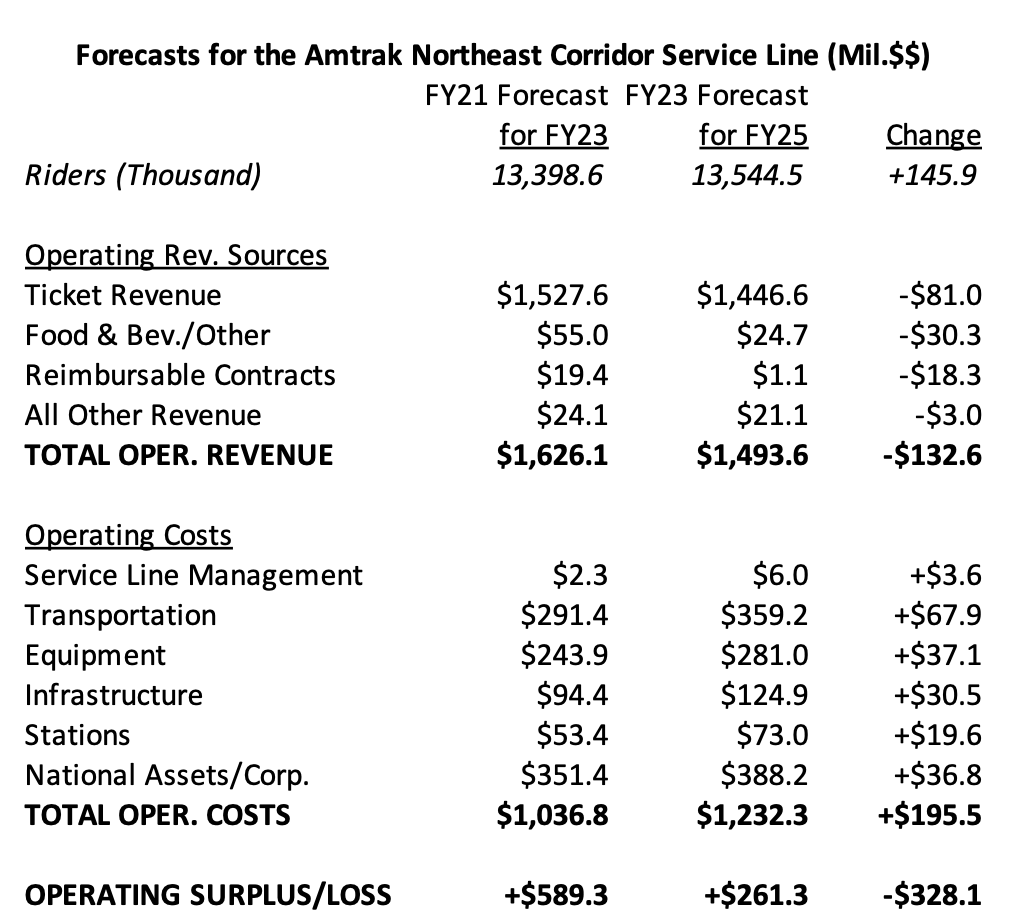

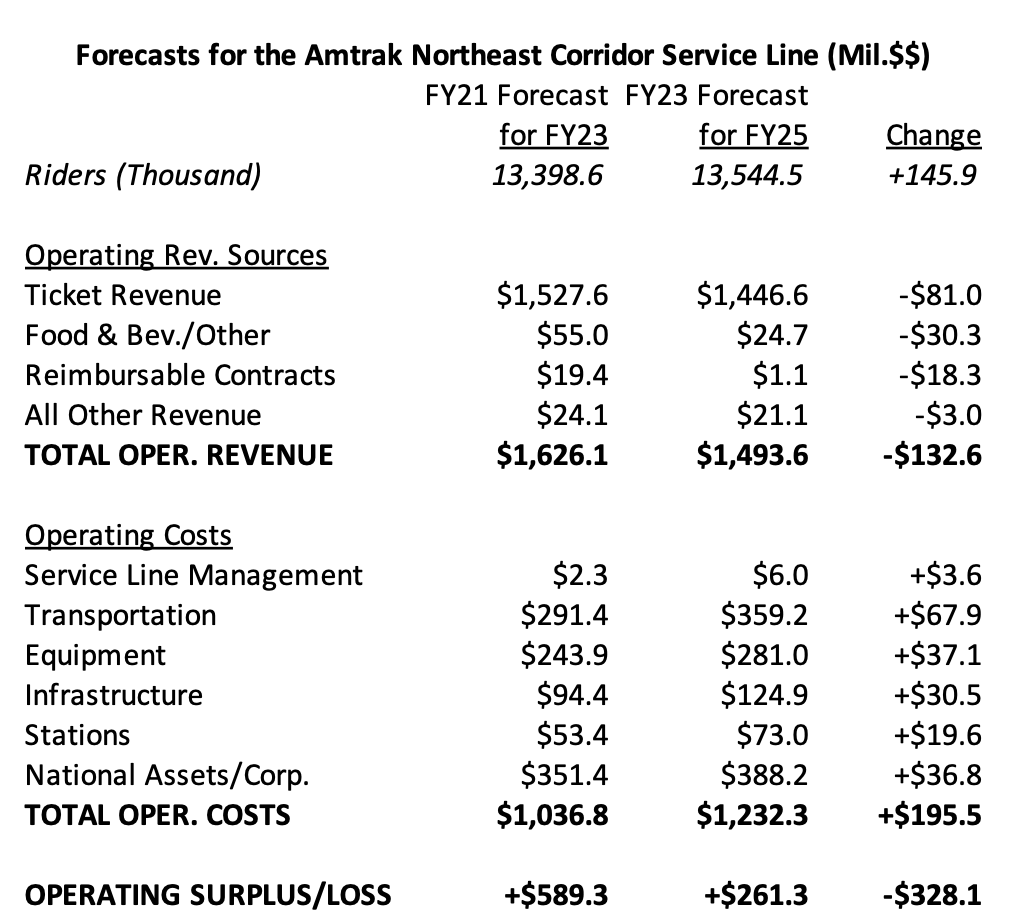

And this is not a ridership problem at all. Nor is this primarily a revenue problem. Let’s look at two hypothetical future years on the Northeast Corridor. First, we have the pre-COVID forecast for fiscal year 2023, which assumed the NEC would have 13.40 million riders. Then let’s compare it to the brand-new forecast for fiscal year 2025, at which point NEC ridership is assumed to be 13.55 million (146 thousand more riders than the earlier forecast):

Even with 146 thousand more riders, Amtrak projects that ticket revenues would be $81 million less, and other revenues would add up to be $88 million less. But operating expenses would be $429 million higher than the earlier scenario of similar ridership.

Another perpetrator is the Infrastructure Access service line. In the last pre-COVID forecast, IA operating losses were expected to hover around $100 million per year forever, since most IA costs are recouped by payments from the state and local governments that use the Corridor and other Amtrak-owned infrastructure. But the new budget shows IA operating losses heading steadily upwards, from the pre-COVID $100 million per year to $450 million per year. We think this is due to the fact that Amtrak bills planning and engineering of projects to the operating budget, not the capital budget, so they are showing their planning for the spending of their tens of billions of dollars in IIJA money out of their annual operating budget, not out of the IIJA money or their annual capital budget.

And then, there are the long-distance trains, which (pre-COVID) were expected to lose around $450 million per year. In the new budget, operating losses for the long-distance trains will almost double by 2027, from the pre-COVID $450 million to $889 million in 2027. And, yes, the new five-year plan book does include, starting on page 226, the ridership projections for each line by year, including allocated profit-and-loss on each train route. They estimate that, in FY 2022, the Sunset Limited will post an operating loss of $614 per passenger, but at least this will drop to $514 per passenger by 2027. The Southwest Chief, which the Senate specifically kept open through the appropriations process a few years ago, is expected to lose $352 per passenger in 2027, up from $237 per rider in 2022.

However, Amtrak can claim with some credibility that Congress, through the IIJA, chose to de-emphasize the issue of operating losses. Look at the changes made by the IIJA to section 24101 of title 49, United States Code, which sets the mission and goals of Amtrak. Old language repealed or changed by the IIJA is in the left-hand column in red italic type, and new language added by the IIJA to replace it is in boldface roman type.

49 U.S.C. §24101 Before the IIJA

|

|

49 U.S.C. §24101 After the IIJA

|

| (b) MISSION.-The mission of Amtrak is to provide efficient and effective intercity passenger rail mobility consisting of high quality service that is trip-time competitive with other intercity travel options and that is consistent with the goals set forth in subsection (c). |

|

(b) MISSION.-The mission of Amtrak is to provide efficient and effective intercity passenger rail mobility consisting of high quality service that is trip-time competitive with other intercity travel options and that is consistent with the goals set forth in subsection (c). |

| (c) GOALS.-Amtrak shall- |

|

|

|

|

(c) GOALS.-Amtrak shall- |

|

|

(1) use its best business judgment in acting to minimize United States Government subsidies, including- |

|

|

(1) use its best business judgment in acting to maximize the benefits of Federal investments, including- |

|

|

(A) increasing fares; |

|

|

|

|

|

(A) offering competitive fares; |

|

|

|

(B) increasing revenue from the transportation of mail and express; |

|

|

|

(B) increasing revenue from the transportation of mail and express; |

|

|

(C) reducing losses on food service; |

|

|

|

|

(C) offering food service that meets the needs of its customers; |

|

|

(D) improving its contracts with operating rail carriers; |

|

|

|

(D) improving its contracts with rail carriers over whose tracks Amtrak operates; |

|

|

(E) reducing management costs; and |

|

|

|

|

(E) controlling or reducing management and operating costs; and |

|

|

(F) increasing employee productivity; |

|

|

|

|

(F) providing economic benefits to the communities it serves; |

|

(2) minimize Government subsidies by encouraging State, regional, and local governments and the private sector, separately or in combination, to share the cost of providing rail passenger transportation, including the cost of operating facilities; |

|

|

(2) minimize Government subsidies by encouraging State, regional, and local governments and the private sector, separately or in combination, to share the cost of providing rail passenger transportation, including the cost of operating facilities; |

|

(3) carry out strategies to achieve immediately maximum productivity and efficiency consistent with safe and efficient transportation; |

|

|

(3) carry out strategies to achieve immediately maximum productivity and efficiency consistent with safe and efficient transportation; |

|

(4) operate Amtrak trains, to the maximum extent feasible, to all station stops within 15 minutes of the time established in public timetables; |

|

|

(4) operate Amtrak trains, to the maximum extent feasible, to all station stops within 15 minutes of the time established in public timetables; |

|

(5) develop transportation on rail corridors subsidized by States and private parties; |

|

|

(5) develop transportation on rail corridors subsidized by States and private parties; |

|

(6) implement schedules based on a systemwide average speed of at least 60 miles an hour that can be achieved with a degree of reliability and passenger comfort; |

|

|

(6) implement schedules based on a systemwide average speed of at least 60 miles an hour that can be achieved with a degree of reliability and passenger comfort; |

|

(7) encourage rail carriers to assist in improving intercity rail passenger transportation; |

|

|

(7) encourage rail carriers to assist in improving intercity rail passenger transportation; |

|

(8) improve generally the performance of Amtrak through comprehensive and systematic operational programs and employee incentives; |

|

|

(8) improve generally the performance of Amtrak through comprehensive and systematic operational programs and employee incentives; |

|

(9) provide additional or complementary intercity transportation service to ensure mobility in times of national disaster or other instances where other travel options are not adequately available; |

|

|

(9) provide additional or complementary intercity transportation service to ensure mobility in times of national disaster or other instances where other travel options are not adequately available; |

|

(10) carry out policies that ensure equitable access to the Northeast Corridor by intercity and commuter rail passenger transportation; |

|

|

(10) carry out policies that ensure equitable access to the Northeast Corridor by intercity and commuter rail passenger transportation; |

|

(11) coordinate the uses of the Northeast Corridor, particularly intercity and commuter rail passenger transportation; |

|

|

(11) coordinate the uses of the Northeast Corridor, particularly intercity and commuter rail passenger transportation; |

|

(12) maximize the use of its resources, including the most cost-effective use of employees, facilities, and real property. |

|

|

(12) maximize the use of its resources, including the most cost-effective use of employees, facilities, and real property; and |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(13) support and maintain established long-distance routes to provide value to the Nation by serving customers throughout the United States and connecting urban and rural communities. |

|

(d) MINIMIZING GOVERNMENT SUBSIDIES.-To carry out subsection (c)(12) of this section, Amtrak is encouraged to make agreements with the private sector and undertake initiatives that are consistent with good business judgment and designed to maximize its revenues and minimize Government subsidies. Amtrak shall prepare a financial plan, consistent with section 204 of the Passenger Rail Investment and Improvement Act of 2008, including the budgetary goals for fiscal years 2009 through 2013. Amtrak and its Board of Directors shall adopt a long-term plan that minimizes the need for Federal operating subsidies. |

|

(d) INCREASING REVENUES.-Amtrak is encouraged to make agreements with private sector entities and to undertake initiatives that are consistent with good business judgment and designed to generate additional revenues to advance the goals described in subsection (c). |

When the IIJA was being debated in Congress, the fact that it was providing a massive, one-time infusion of capital funding to build down Amtrak’s long-term capital backlog ($22 billion over five years) was well-known. And the $36 billion for new intercity passenger rail capital grants (many of which will be in partnership with Amtrak) and the $5 billion for “megaprojects” (which might also be used for Amtrak-related capital) were also major selling points for the IIJA.

But the fact that the IIJA was de-emphasizing the minimization of federal operating subsidies as an Amtrak goal was not widely advertised (despite being clearly present from the point the draft bill text was released just prior to the Senate Commerce Committee’s June 16, 2021 markup). And, if Senators knew that Amtrak was going to use use the new language to justify abandoning any hope of future subsidy reduction and instead return to the perpetual ward-of-the-state, federally subsidized operating losses of $1 billion per year, they didn’t mention it during debate prior to passage of the bill.

And it should be noted that the IIJA did not actually provide any money to pay for the perpetual operating losses that it implicitly authorized Amtrak to incur – all of the IIJA funding, by law, can only go to capital projects. Those subsidies will have to be paid out of future annual appropriations bills, at a time when the attitude towards federal deficits might be different than it was when the IIJA was going through Congress last year. (Deficits encourage inflation, after all.)

It will be up to the House and Senate Appropriations Committees to either write the checks for the billion-per-year operating losses over the coming decade, or else use their annual platform to encourage (or require) Amtrak to pay attention to operating losses if they want to avoid writing those checks.