(Part one of this series told the story of how Congress passed, and Richard Nixon at the last minute decided to sign, the October 1970 law establishing a national passenger railroad operator. Part two explained how, from November 1970 to January 1971, the Nixon Administration selected the “Basic System” of endpoint routes that the new railroad would be required to serve for at least two years. Here, part three explains how a small group of incorporators, and a small army of consultants, created an operational passenger railroad from scratch in four months.)

Naming the Incorporators

The Rail Passenger Service Act of 1970 gave a lot of specific direction as to what the new National Railroad Passenger Corporation was supposed to do once it became operational on or before May 1, 1971. But it didn’t give much direction as to how the corporation was supposed to get established and become operational. The only instructions were in section 302 of the law:

SEC. 302. PROCESS OF ORGANIZATION. The President of the United States shall appoint not fewer than three incorporators, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, who shall also serve as the board of directors for one hundred and eighty days following the date of enactment of this Act. The incorporators shall take whatever actions are necessary to establish the Corporation, including the filing of articles of incorporation, as approved by the President.

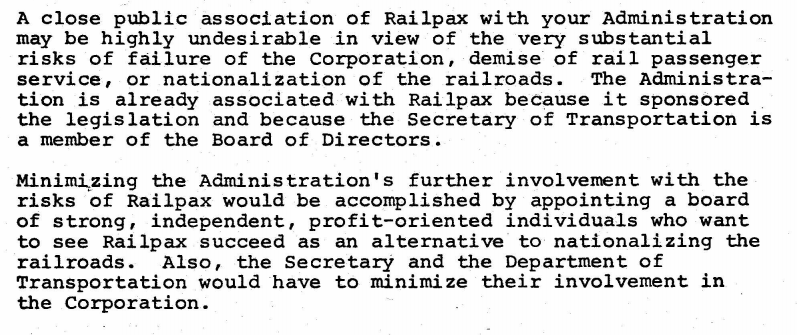

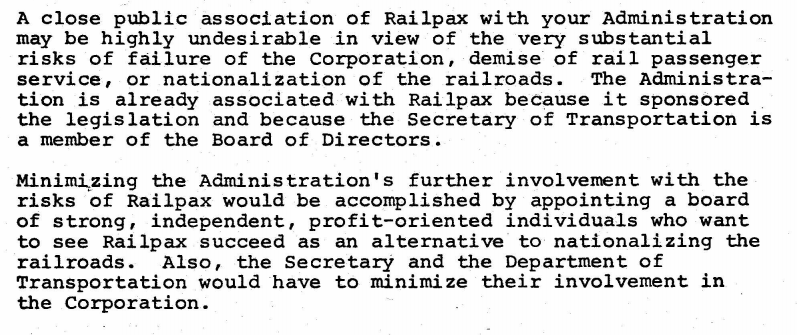

Richard Nixon’s decision to sign the bill into law was a narrow thing, with his budget and economic advisers recommending a veto but with Transportation Secretary John Volpe implicitly threatening to resign, days before the midterm elections, if he vetoed it. In the aftermath of the signing, White House budget director George Shultz, sent Nixon a memo urging that the new corporation be kept at arm’s length from the Administration:

On December 18, 1970, Nixon announced eight nominees to serve as a Board of Incorporators for the forthcoming NRPC. Most had significant transportation experience, but none had worked in management for U.S. railroad companies:

- Frank S. Besson, Jr. A recently retired four-star general and career logistician, Besson had served as head of the Army’s railway division during WWII, then served as chief of transportation for the Army before taking over as the first head of the Army Materiel Command. He then ran the Joint Logistics Review Board before retiring earlier in 1970.

- David E. Bradshaw. A prominent attorney in Chicago, Bradshaw later founded and ran the Kenilworth Insurance Company.

- John J. Gilhooley. An attorney from New York who had served as an Assistant Secretary of Labor in the Eisenhower Administration, Gilhooley then served as Commissioner of the New York Metropolitan Transit Authority for six years before forming his own company earlier in 1970 to buy out New Jersey’s largest bus company.

- David W. Kendall. An attorney who served as General Counsel at the Treasury Department (and later Special Counsel to the President) under Eisenhower, Kendall had been General Counsel for Chrysler Corp. from 1962-1968 before going into private practice in Detroit.

- Arthur D. Lewis. A career airline executive, Lewis worked for American from 1941-1955 before being recruited to take over troubled Hawaiian Airlines in 1955. He later went to Eastern Airlines in 1964 and became CEO before retiring in 1969.

- Charles Luna. Luna started work as a switchman for the Santa Fe Railroad in 1928 and got involved in his union, gradually rising up in the Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen and becoming President of the union in 1963.

- Catherine May. A six-term U.S. House member (R) from Yakima, Washington, May had just been defeated for re-election in November 1970 by a Democrat. Although she had not served on any transportation committees in the House, she had served on Nixon’s Key Issues Committee on his campaign. (On November 16, 1970, May had remarried and was in the process of changing her last name to Bedell as she started her service on the Board.)

- John P. Olsson. At the time of his nomination, Olsson had been at USDOT for eight months, as Deputy Under Secretary, after a career as a finance and budget officer in the mining industry.

Getting started, and hiring McKinsey

Even before their Senate hearing, the incorporators held an informal meeting on December 22, 1970, where they met with Secretary Volpe and other USDOT personnel. (Every reference in this article to a meeting of the incorporators is taken from the minutes of those meetings, which we have posted online here.) [1]

Their first actions that day were to begin the task of selecting service providers – law firms for legal services, executive recruiting companies for headhunting, and outside accounting firms to go over Railpax and private railroad books. They also “Requested DOT to broaden its contract with McKinsey to include organizational and job/salary schedules.” This was expanded at the January 12-14 meetings so that Railpax would directly “hire McKinsey & Co. to provide interim staff support and be available for special projects. Agreement was decided to be open-ended to afford the Board flexibility.”

McKinsey would be the biggest and most influential outside contributor to the work of the incorporators setting up Railpax in early 1971. Their team was led by Robert Neuschel, who later went on to a distinguished career as a professor at the Kellogg School. Other McKinsey personnel who worked on the Railpax startup included George McIsaac and future Delta Air Lines CEO Leo Mullin.

One of the few people who had worked on the Railpax project as a Department of Transportation employee and who then went to work immediately for the incorporators was Jim McClellan. He later wrote, “The FRA detailed me to assist the incorporators in this startup effort…The very bright, energetic incorporators were supported by an army of consultants…I was overwhelmed by the army of McKinsey folks–at the DOT/FRA I was a relatively big fish in a small pond, and now the pond was much bigger and my participation was less important. Perhaps I resented giving up control to a group of hired guns who were not really all that interested in the outcome.”[2]

President Nixon had formally requested the full $40 million startup appropriation for Railpax on December 3, which was making its way through Congress in a supplemental appropriations bill (H.R. 19928, 91st Congress). It cleared Congress on December 28, 1970 and became law on January 8, 1971. During their three-month existence, the Board of Incorporators would eventually budget $4 million of that $40 million towards startup costs – a little over $3 million for salaries and direct expenses, and the remainder on that “army of consultants.”

Arthur Andersen would review the books of the railroads whose ongoing passenger service was going to be taken over by Railpax (except where Andersen had a conflict, in which case Arthur Young stepped in). The headhunting duties were split between two firms (who would cooperate on the search for a CEO and split up the recruitment for other positions between them). Engineering firms were hired, mostly to review the state of the locomotives, railcars, and terminals that were being given to Railpax by the freight railroads. American Airlines established the initial national ticketing and reservation system. Legal and PR advisers were also hired.

And relations with Congress were not ignored, either. As detailed in part one of this series, the head of Congressional liaison for USDOT during 1970, who had worked with Congress on the Railpax bill, was Bob Bennett (son of Utah Republican Senator Wallace Bennett). At the beginning of 1971, Bennett left DOT and bought a Washington DC PR/lobbying firm from its founder, Robert R. Mullen. Incorporator Catherine May Bedell then hired the Mullen company so Bennett could help Railpax with Congressional relations. (See this bizarre 1976 New York Times article for all the Mullen/Bennett connections to Howard Hughes and the Watergate burglars at around this time.)

| Professional Services Firms Hired by the Railpax Board of Incorporators |

|

|

Railpax |

In 2021 |

|

|

Contract |

Dollars |

| Management |

McKinsey |

$545,000 |

$3,608,949 |

| Accounting |

Arthur Andersen |

$500,000 |

$3,310,963 |

| Accounting |

Arthur Young |

$50,000 |

$331,096 |

| Exec. Recruitment |

Hendrick & Struggles |

$150,000 |

$993,289 |

| Exec. Recruitment |

Ward Howell |

$175,000 |

$1,158,837 |

| Engineering |

Louis T. Klauder |

$450,000 |

$2,979,866 |

| Engineering |

Parsons Brinkerhoff |

$40,000 |

$264,877 |

| Misc. |

other |

$20,000 |

$132,439 |

| Legal Fees |

mostly Jones Day |

$600,000 |

$3,973,155 |

| Corporate Image |

Lippincott & Marguiles |

$125,000 |

$827,741 |

| Public Relations |

Harshe-Rotman & Druck |

$75,000 |

$496,644 |

| Ticketing/Reservations |

American Airlines |

$138,000 |

$913,826 |

| Advertising |

various |

$100,000 |

$662,193 |

| Public Relations |

Robert R. Mullen Co. |

$20,000 |

$132,439 |

| TOTAL |

|

$2,988,000 |

$19,786,312 |

On December 28, the incorporators met again and had a sit-down with Senator Vance Hartke (D-IN), chairman of the Senate transportation subcommittee, in preparation for their confirmation hearing before Hartke’s committee the following day. At that hearing, complained about Nixon’s delay in appointing the incorporators. A few of the questions from committee members were specific (Sen. John Pastore (D-RI) told the nominees that if they chose to route the Boston to New York route through Springfield, Massachusetts instead of through Providence, Rhode Island, the corporation would lose his support), most were general in nature.[3] The incorporators were confirmed by the Senate unanimously on December 30.

McKinsey and the incorporators create an organization

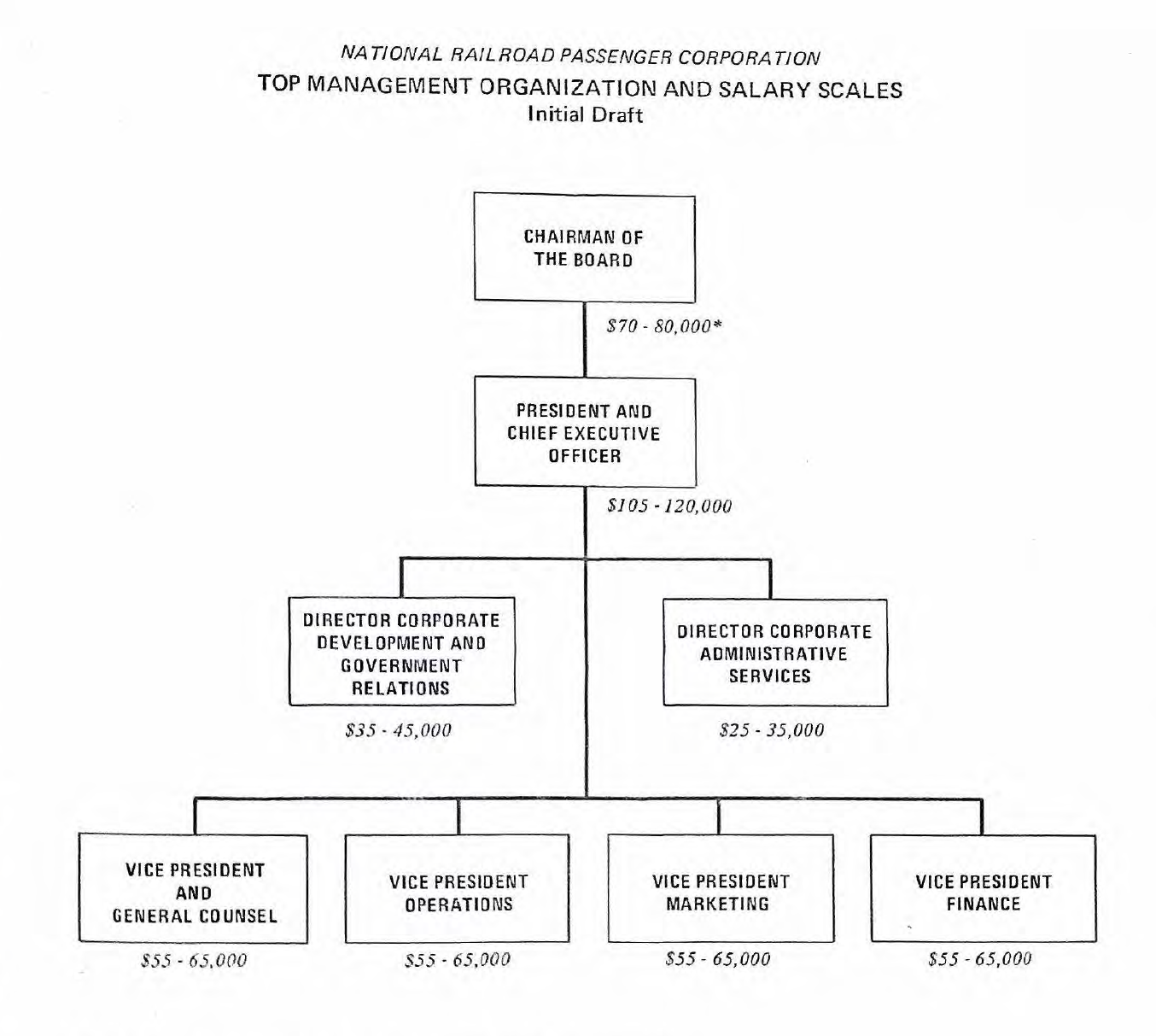

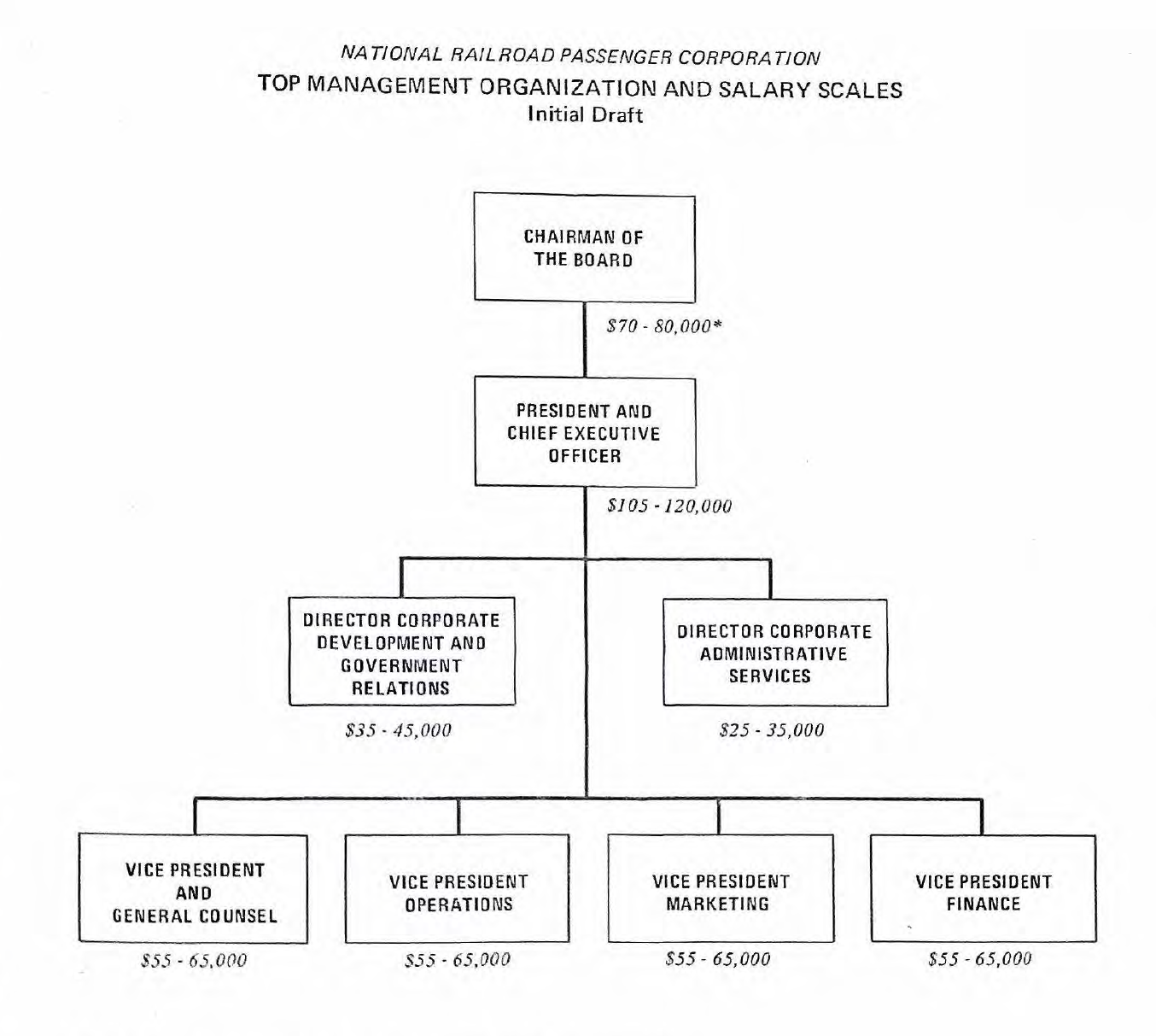

After the morning hearing on the 29th, the incorporators met with McKinsey to receive their initial proposal for how to organize the new railroad. McKinsey told the incorporators that “It is mandatory that the new Corporation be designed as a streamlined – ‘bare bones’ type of organization…to gain the maximum possible flexibility, inherent in a simple, straightforward structure, permitting more sophisticated variations should the need become justified at a later date.” They also recommended, at least for the short term, “a functional type organization, both centrally and in the field. This is typically the least expensive to staff and builds the flexibility to shift in the future, for example, to a more structured regional type field organization (i.e., field general managers having both operations and marketing under their control) should that appear more appropriate to the Corporations’ needs.”[4]

The McKinsey report acknowledged that the May 1 startup date was looming soon, and suggested “having on board, at a minimum, some 8-10 key executives and a small supporting staff by the May 1 kick-off date.”[5] The report included summaries of the job descriptions and recommended pay levels for the top eight officers of the company, as shown in this proposed organizational chart.

McKinsey also recommended a bare minimum number of key activities that had to be in operation by the May 1 deadline:

Established contractual arrangements covering the operation and servicing of trains

Workable standards of performance to ensure that an appropriate level of service is performed and there is a basis for measuring results

Determination of the principal “service packages” to be offered to the transportation public

The key accounting and financial practices in place necessary to carrying out legal accounting functions and exerting sound fiduciary control over receipts and expenditures

Establishing continuing relationships with key government bodies, the rail industry, and the transportation public.[6]

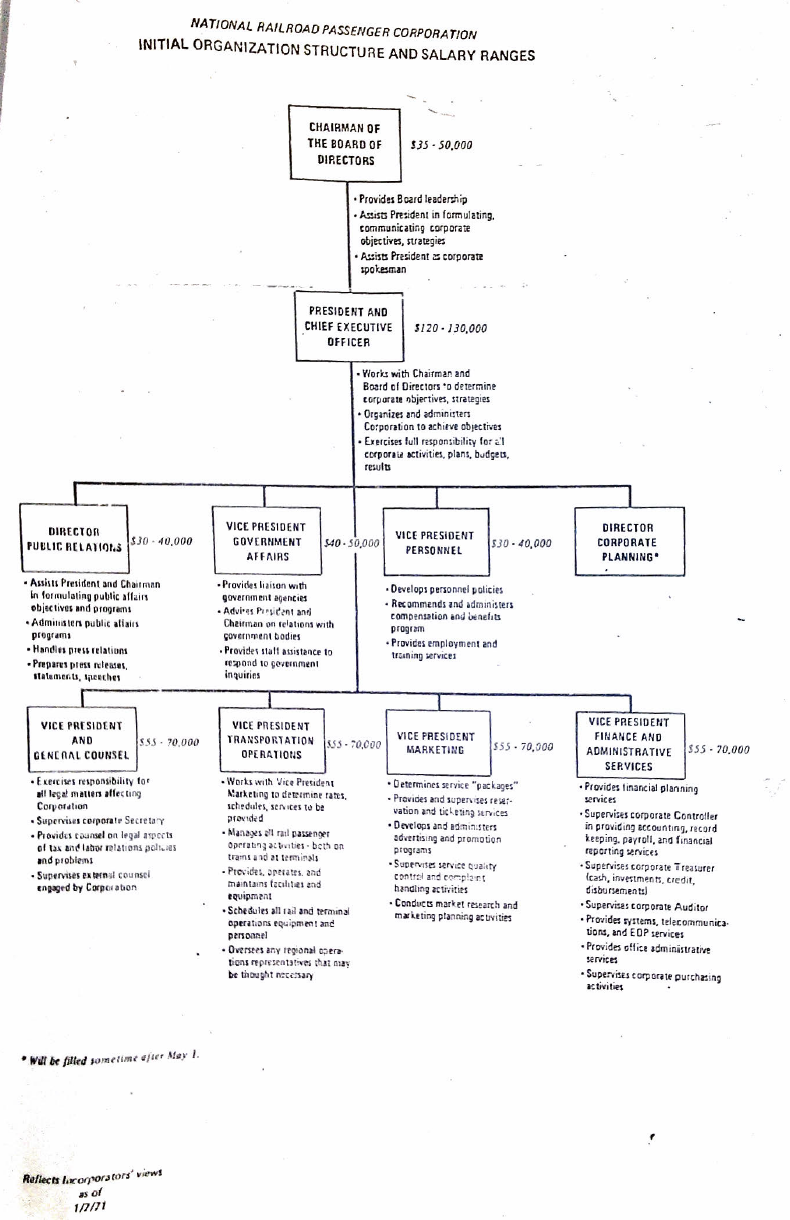

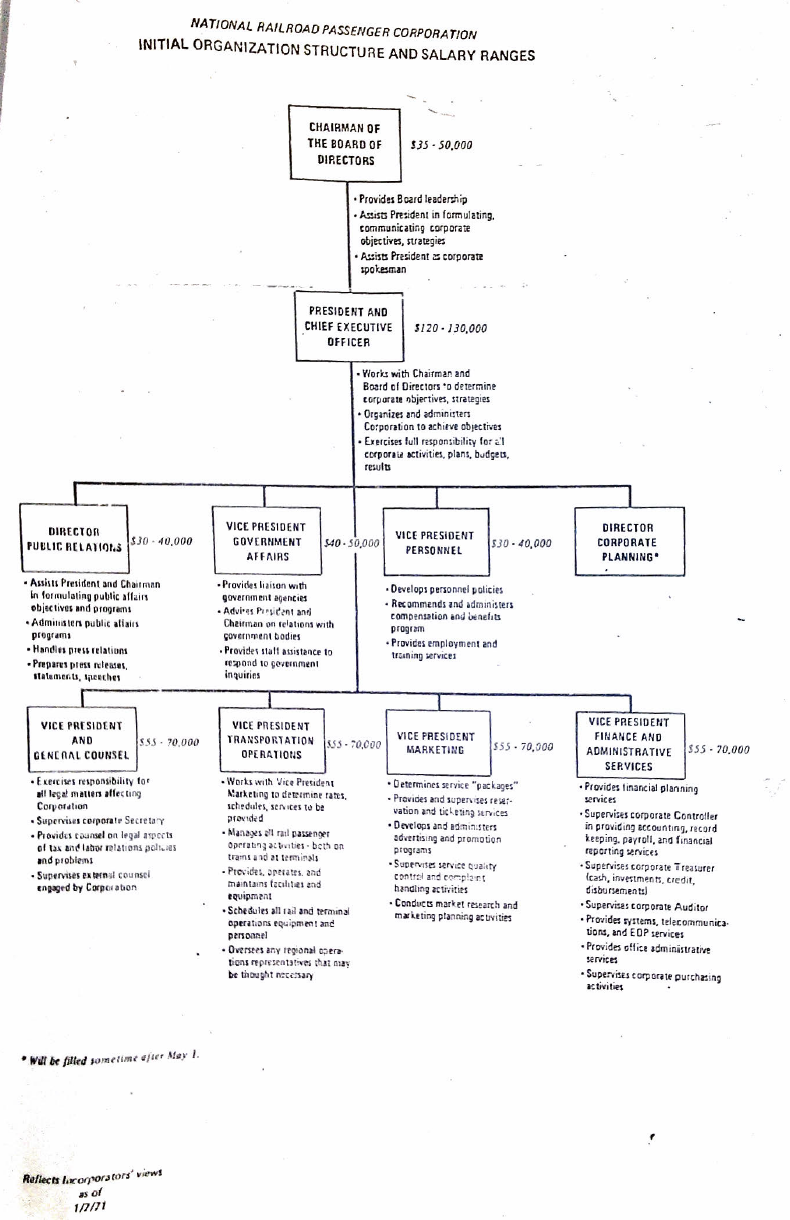

At their first meeting after being confirmed by the Senate, over the three days of January 5-7, 1971, the incorporators approved a slightly revised version of the McKinsey plan for organizing the new company and set the headhunting firms to finding candidates for the executive positions. The revised org chart added a director of public relations, elevated government affairs to its own vice presidency, and moved administrative services in with the finance department.

By the next meeting (January 19-21), the incorporators had elected David Kendall chairman and Frank Besson vice chairman, and had given every member of the board specific areas of responsibility: “Lewis – advertising, public relations, corporate identity, personnel; Olsson – financial, accounting; Bedell – consumer matters, congressional, office management; Bradshaw – legal, insurance liability; Luna – new business, rail operations/contracts; Besson – rail operations, equipment; Gilhooley – legal, equipment.”

They had just over three months until the railroad was supposed to be operational.

McKinsey and the incorporators select routes

Secretary Volpe had already finalized the Basic System of endpoint routes that Railpax would be required to serve. But it was left up to the incorporators to choose which specific lines between those endpoints would be served, as well as the frequency of service and the “train consist” (the number and type of cars). Collectively, the results of these decisions would be called a “service package” for an endpoint-to-endpoint route.

Jim McClellan later wrote, “McKinsey was charged with deciding which specific routes and which specific trains should be run…The McKinsey crowd was bright, but most of them lacked any knowledge of the rail passenger business. They did know that the choices made would be hotly contested, so criteria were established that laid down the basics…”[7]

At the February 11 meeting, those basics were announced: “Mr. Neuschel of McKinsey led the Board’s first full discussion of service package specifications by reviewing the criteria and approach to route and other service package element (e.g., train frequency) selection decisions.” The incorporators “indicated their satisfaction with the approach” recommended by McKinsey, which was as follows:

- First, evaluate all the endpoint routes in the Basic System against three criteria: (a) size of market for passenger service; (b) physical characteristics of route and track; and (c) current train ridership.

- Second, eliminate some “unattractive alternative routes” out of hand. Criteria used for this elimination included: (a) no current passenger service, (b) low market potential, (c) comparatively poor track conditions, (d) longer or slower routes than alternatives, and (e) comparatively poor ridership.

- Third, make detailed comparisons for the remaining route segment alternatives based on market size, physical characteristics, train ridership, and profitability.

- Finally, recommend a single route for each Basic System endpoint set to the incorporators for their consideration.[8]

On February 18, “Mr. Neuschel reported on a meeting the previous night with several railroad executives” with whom he had reviewed some preliminary route selections, to the railroad men’s satisfaction. The incorporators then sat down with their McKinsey team and representatives of the Seaboard Coast Line, the Southern Pacific, and the Illinois Central to evaluate some potential routes.

Importantly, at this meeting the incorporators agreed that “service on May 1 would not be instituted on a route that does not now have service…all agreed that service could in any case be added later.”

The incorporators held another meeting with their McKinsey team on February 24 to go over the rest of the routes. Neuschel framed the choices for them as their duty to balance two competing needs: “1. Cost/profit economics that exist at present, and 2. Service to the public – immediately and over the longer term. Further, he stated that these considerations will sometimes conflict and must be carefully weighed by the Incorporators in making their decisions on how to serve the 21 basic city-pairs and/or provide additional service.”

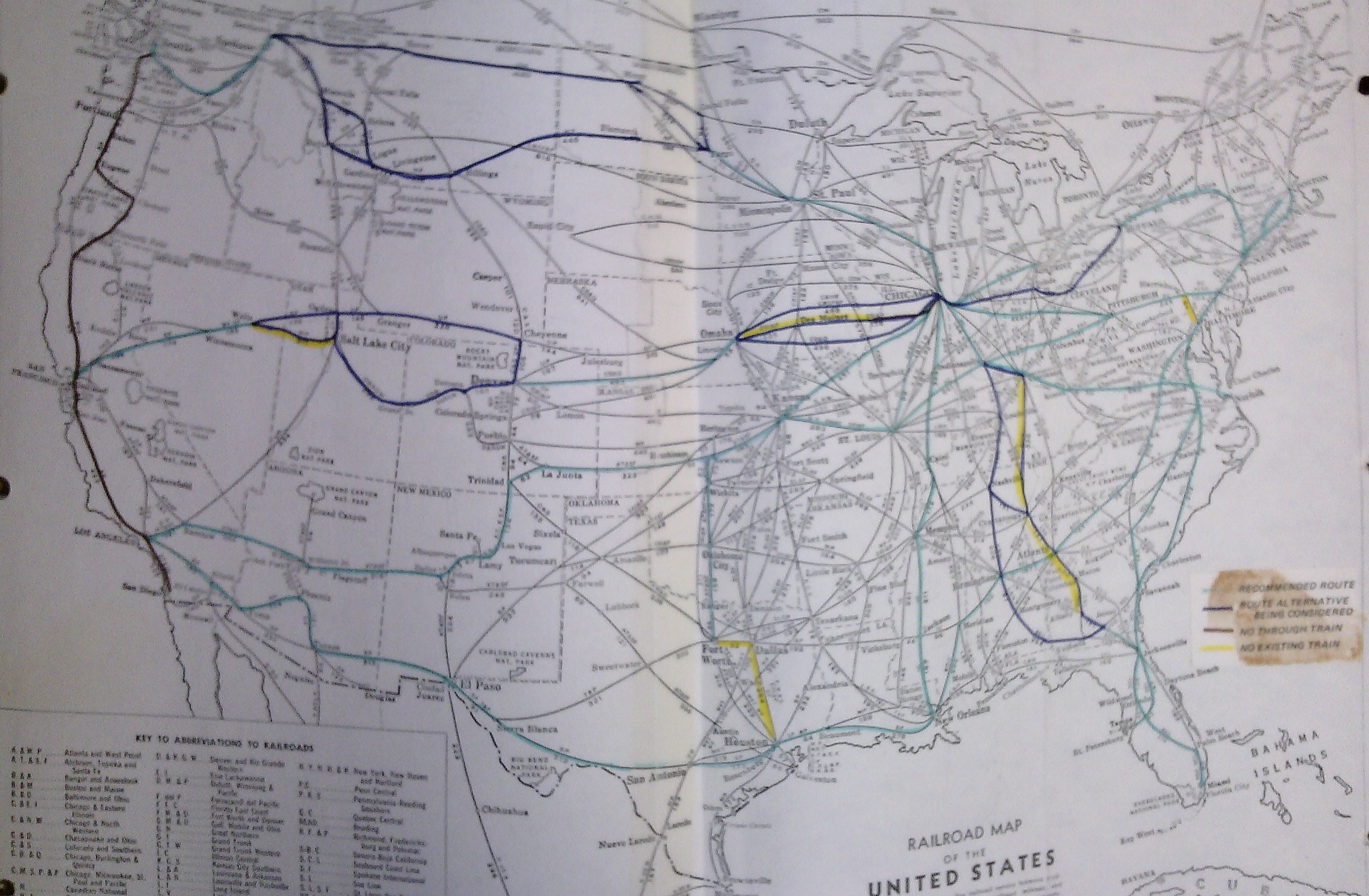

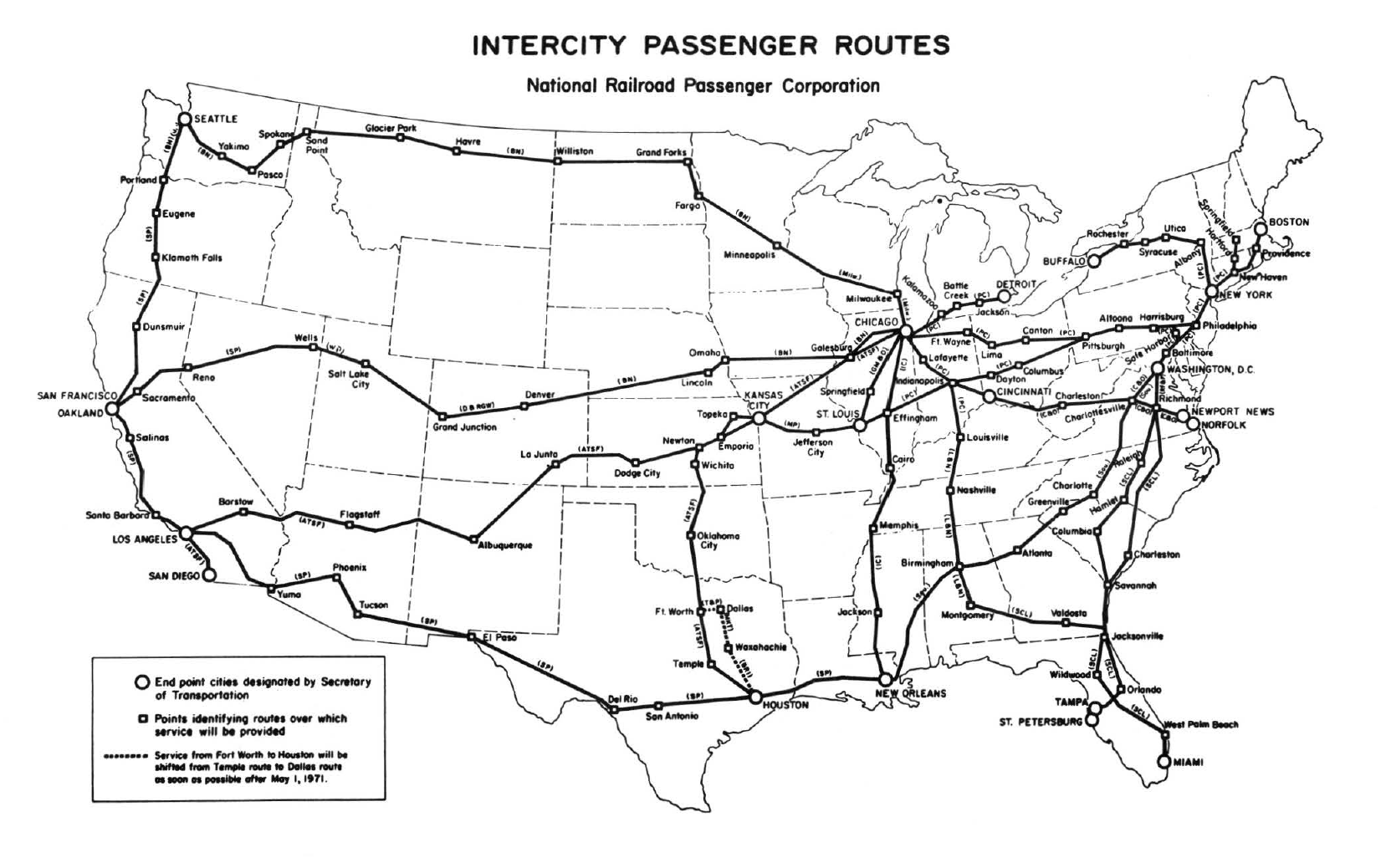

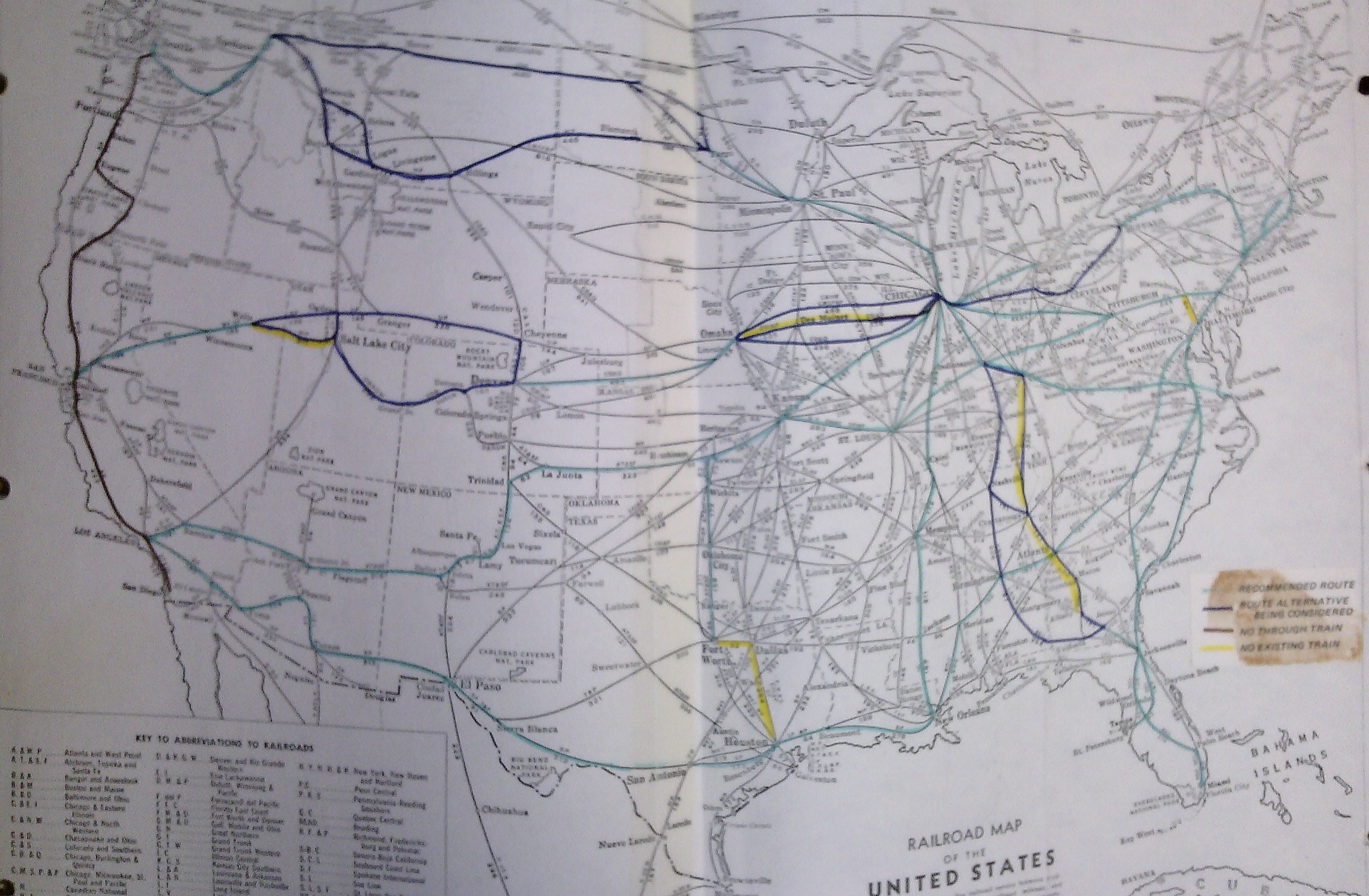

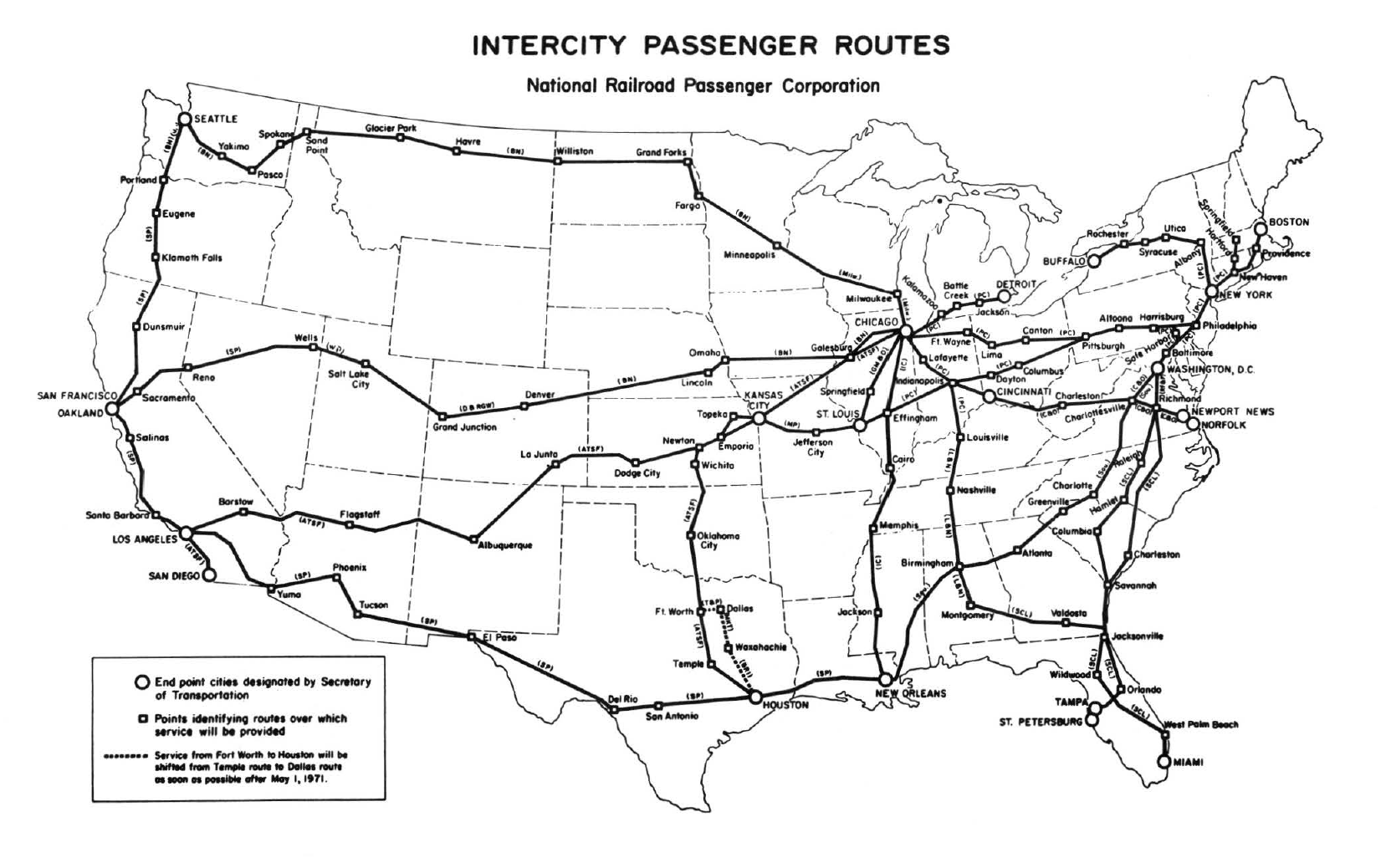

By March 11, the incorporators were ready to start making the final route decisions. McKinsey had presented them with a 273-page three-ring binder which contained their recommendations and analysis. The analysis was prefaced with a map of the proposed new system (shown below): light blue lines were recommended routes, dark blue lines were alternatives for study, and alternatives that were also highlighted in yellow were alternative routes which currently did not have passenger service.

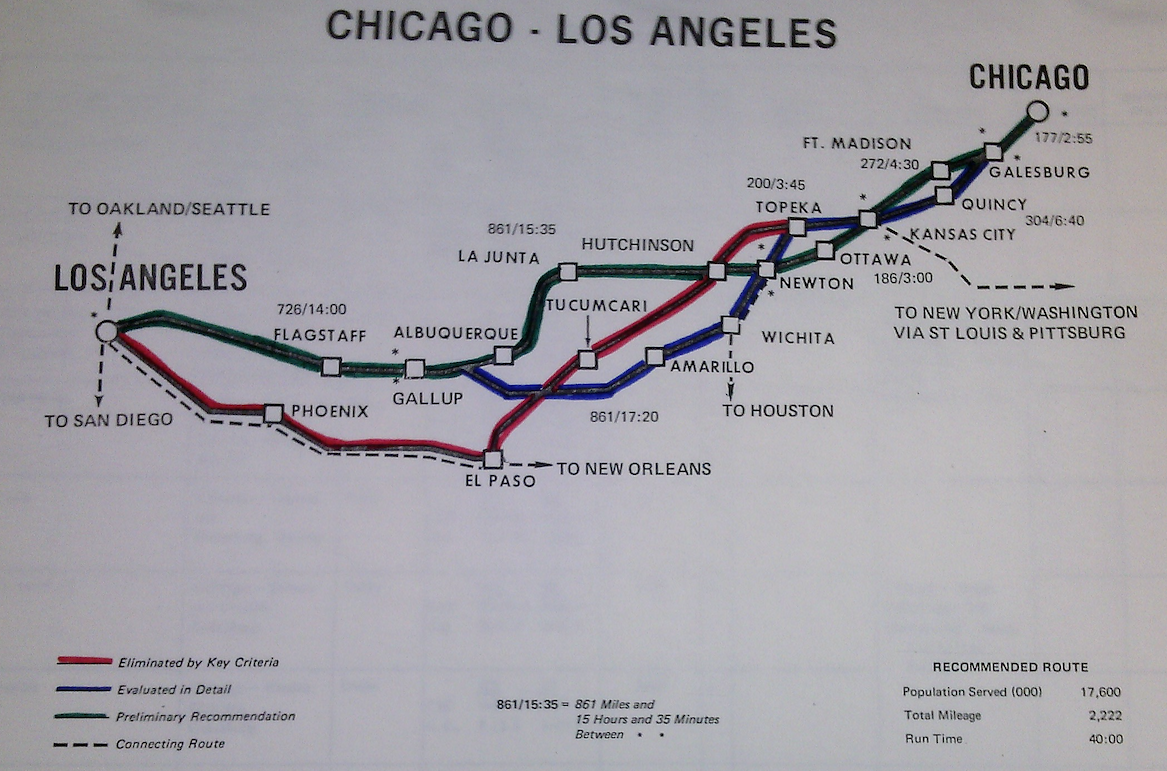

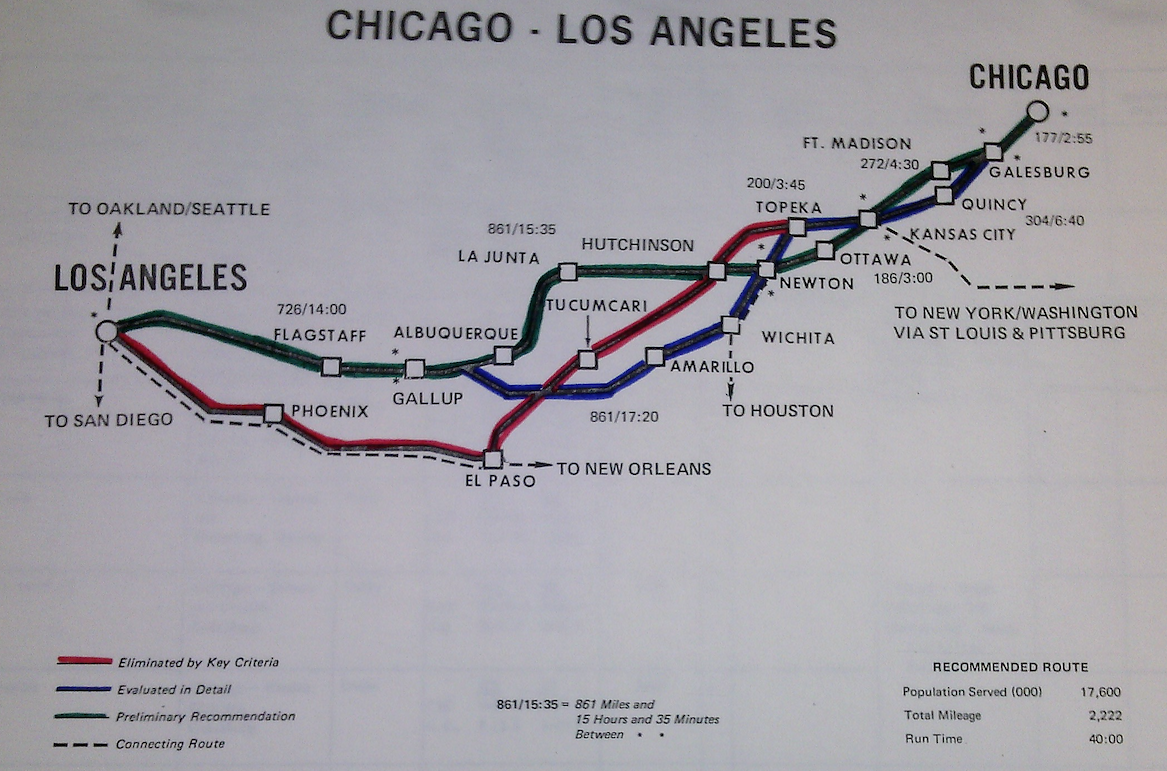

For each set of endpoints on the Basic System, McKinsey had prepared a chapter in the binder, which started off with a color-coded map (red for routes eliminated out of hand due to the above criteria, green for recommended routes, and blue for alternative routes evaluated in detail for discussion), and was followed by several pages of data and analysis on existing trains along that route, market potential of cities along the route, etc. For example, here is the specific alternative map for the Chicago to Los Angeles segment.

McKinsey recommended routing the Chicago to Kansas City segment along the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe line through Fort Madison instead of the Burlington Northern line through Quincy, because the ATSF line was 32 miles shorter and over two hours faster, and because Fort Madison contributed 40 percent more passenger-miles than Quincy, based on past ridership.

Similarly, McKinsey recommended that, going west from Kansas City, the route go through Ottawa, Kansas, instead of Topeka, because even though Topeka was the state capitol, it already had Interstate highway service and because the Ottawa route was 15 miles shorter and 45 minutes faster.

Moving farther west, McKinsey recommended using the northern ATSF route from Newton, Kansas to New Mexico (via Hutchinson and La Junta) instead of the southern ATSF route through Wichita and the Texas panhandle, because the scenery was nicer and it was a much better route for on-time performance. (An alternate Southern Pacific route through El Paso and Phoenix was rejected out of hand because half of it had no current passenger service to begin with and the other half was duplicative of the New Orleans to L.A. route.)

Per the minutes of the meeting, “The Board resolved unanimously to: a. Run the route via Ottumwa [sic] and La Junta-Albuquerque as recommended; b. Provide 1 train per day each way (the current Super Chief); c. Accept the recommended schedule and consist.”

On that day, the incorporators also accepted the McKinsey recommendations for the specific routes for Seattle-San Diego, New Orleans-Los Angeles, Chicago-St. Louis, and Chicago-New Orleans. At the March 13 meeting, they accepted the McKinsey recommendations for the New York-New Orleans, Chicago-Cincinnati, Norfolk-Cincinnati, New York-Florida, and Chicago-Florida routes (the latter of which went through Nashville and Birmingham instead of Chattanooga and Atlanta because of their “no service where none now exists” rule). Then, at the March 16 meeting, they accepted the McKinsey recommendations for the Detroit-Chicago, New York-Boston, New York-Buffalo, New York-Kansas City, New York-Chicago, D.C.-St. Louis, D.C-New York, and D.C.-Chicago routes. They also finalized unfinished business from the March 11 meeting, including approval of the recommended route of the Chicago-San Francisco line through Salt Lake City.

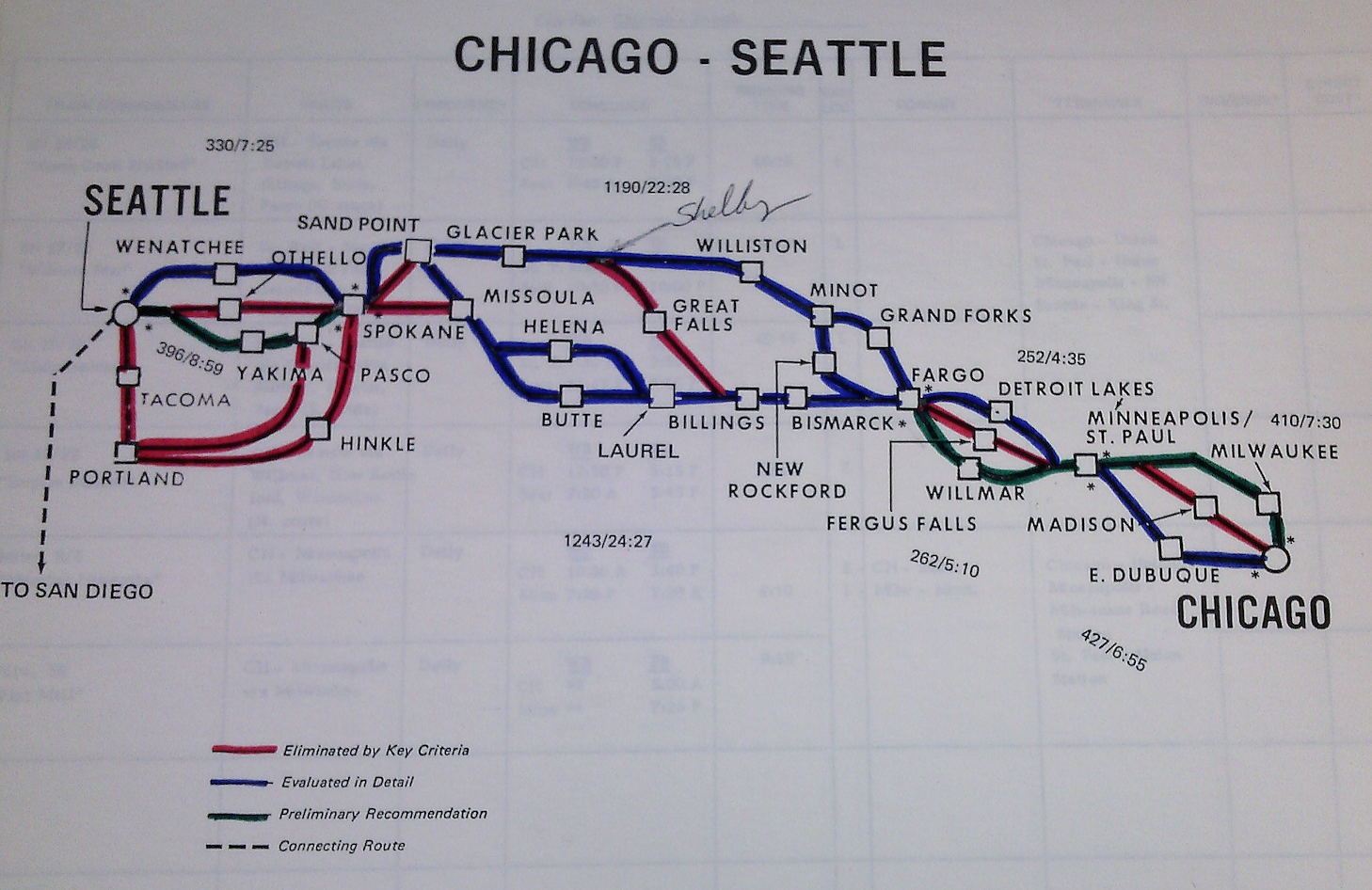

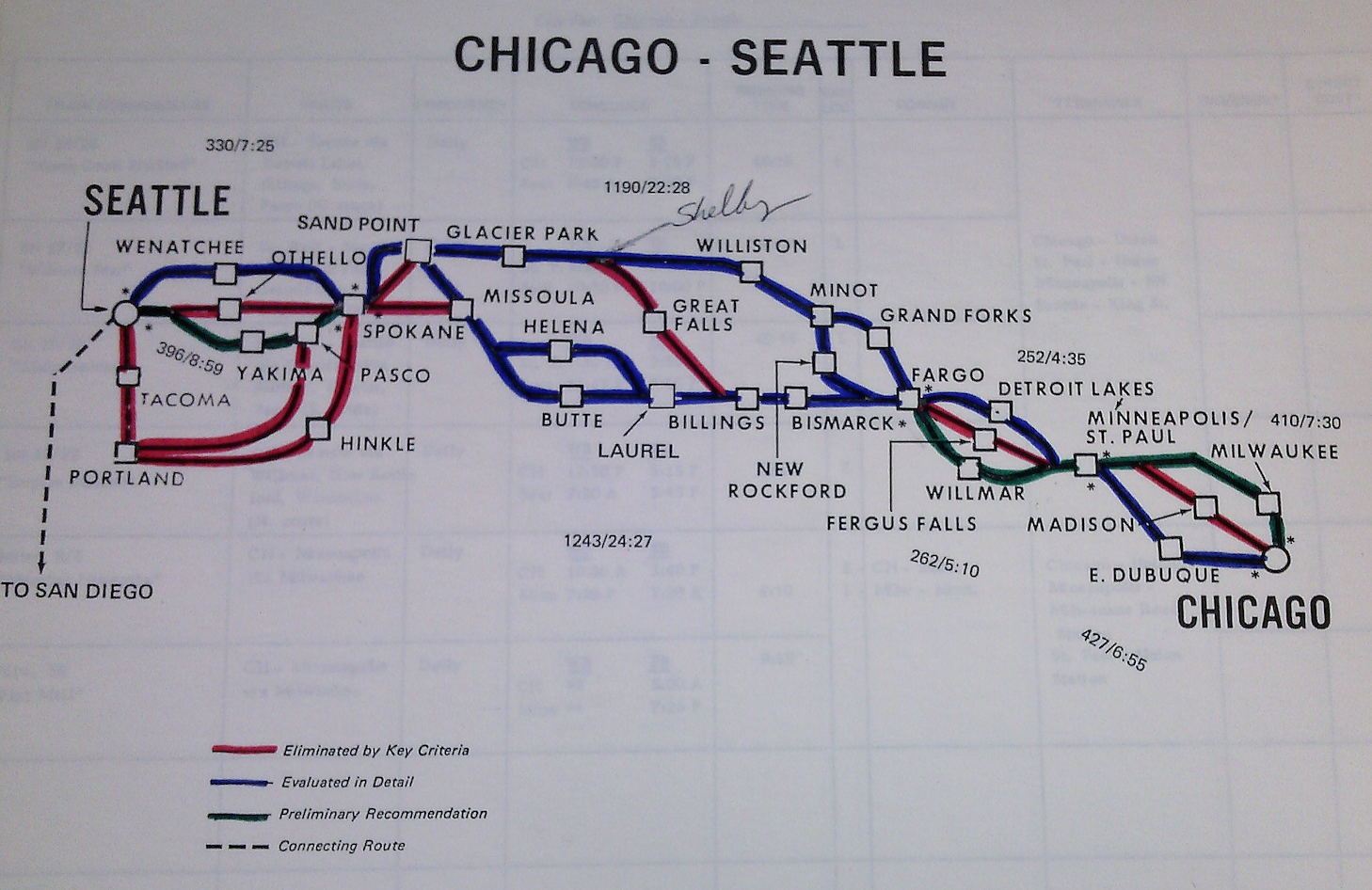

They also chose a route to go through North Dakota and Montana, which is still questioned by Montana politicians today. In the 1800s, two competing railroads had built east-west lines running the length of Montana. The Great Northern line went from Fargo, North Dakota northwest to Grand Forks and Minot, then due west to Glacier Park and Sand Point, before heading south to Spokane. The Northern Pacific line went due west from Fargo to Bismarck, then southwest to Billings and Butte before heading back northwest to Missoula and thence west to Spokane. (Both lines were now owned and operated by the same company, Burlington Northern, since a 1970 merger.)

The options map that McKinsey presented to the incorporators for the Chicago-Seattle route looked like this:

Of the two main choices between Fargo and Spokane, the McKinsey team laid out the options:

- “Northern route contributes 30 million more passenger miles than southern route

- “Northern route is 2 hours faster than southern route

- “Southern route serves 50% more population than southern route – 250,000 versus 160,000 (Total Chicago-Seattle market is 16,000,000 people)

- “Cities and Glacier Park along northern route have little other transportation available to them, while the southern route is served by an interstate highway”

The incorporators unanimously chose the northern route.

Now that they had made the hard decisions on route selection, they had to announce them to the public.

Announcing the routes to the public

The incorporators called a press conference for 2 p.m. on Monday, March 22, 1971 to make their route announcements. In anticipation of that, Catherine May Bedell and Bob Bennett formed a strategy for giving key Members of Congress some advance notification of the routes selected.

Each incorporator was assigned a few key members of Congress and was told to make personal telephone calls to them on Friday, March 19 to talk about the routes. Each incorporator was also given some talking points to prepare them for the most likely questions, like this:

QUESTION: “Are you giving us passenger service on route “x”?”

SUGGESTED GUIDE-LINE ANSWER: You must be honestly responsive to this question because the Senator or House Member has a right to ask it and would not accept an answer that indicated he had to wait until Monday morning like everyone else.

So be prepared to anticipate what route the Member of Congress might be interested in and have your answer ready for him. Answers should include principal cities, route and frequency of service.[9]

At the press conference, board chairman David Kendall said:

What we are announcing today represents our best judgment. We realize that others may take issue with us. We hope that they will realize that we were confronted with enormous problems of money, track conditions, inadequate equipment, and lack of apparent potential for future passenger growth. Given existing conditions, we think that we have made the best possible decisions.

In effect, we have tackled an extremely complex situation and converted it into the beginnings of an efficient system. We are taking the best equipment – some 1,500 out of 3,300 existing railroad passenger cars – operated by 22 different railroads, with a mass of schedules that for the most part are not coordinated with another and losing more than $235 million annually.

Initially, our objective is to cut these losses by over 50 percent and we believe that we have started a turn-around that will eventually provide the American people with a highly desirable service that can be profitable and which will appeal to an ever increasing number of travelers.[10]

Kendall also took pains to refer complaints to state governors and legislatures: “It cannot be emphasized too strongly that Section 403 of the Rail Passenger Service Act allows the Corporation to add service where a state, regional or local agency feels strongly enough to reimburse the corporation for at least two-thirds of the cost of this service. We are exploring a number of such situations.”[11]

Railpax personnel then handed out a press kit that included an abbreviated version of the route-by-route evaluations prepared by McKinsey and a list of all stops to be made, along with a map of the national system:

(The press strategy paid off – at a later meeting, the incorporators were told that “In many cases 20-90% of stories carried in newspapers (and the editorial reaction to them) were based on press kit material”.)

Choosing a new name

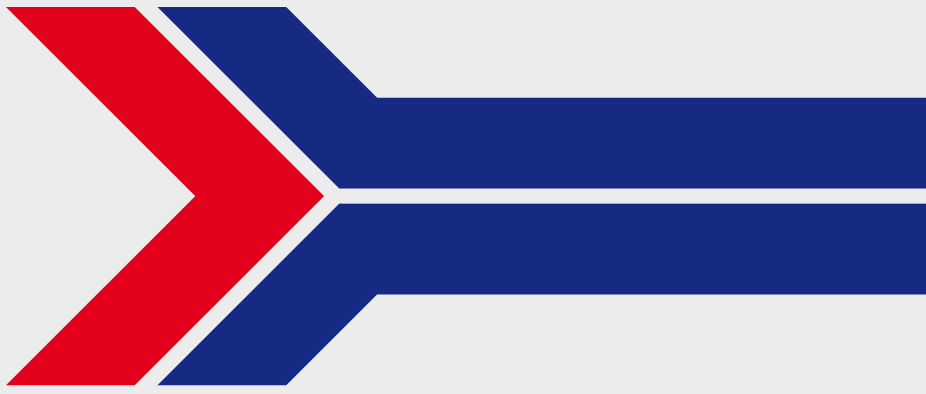

The May 22 press conference would be the last one held by the nascent railroad under the name “Railpax.” At the March 30 meeting of the incorporators, Walter Marguiles, co-head of the brand consultancy Lippincott and Marguiles, briefed the board on the results of their $125,000 contract to find a new name and brand for the railroad.

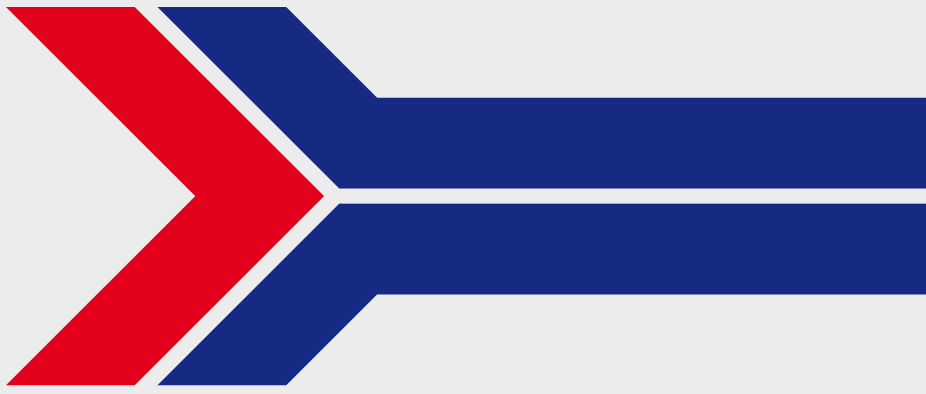

L&M were the kings of logo design – at this point they had designed the Campbell’s Soup can, the spoon logo for Betty Crocker, the Citgo red triangle, and the curved ribbon on the Coca-Cola logo. Before choosing a railroad name, Marguiles asked them to choose one of three finalists for a logo design. From the minutes: “The Incorporators present unanimously selected the primary L&M recommendation (an arrowtail-like design in red, white and blue.)”

Having selected a logo, Marguiles recommended three possible names for the new corporation: TRAK, AMTRAK, and SPAN. The incorporators voted, and it was a tie – 3 votes for TRAK, 3 votes for AMTRAK, and 1 vote for SPAN. After discussion, the board settled on AMTRAK, supporting that name unanimously.

The new railroad had a route map and had a name. But with one month to go before the startup date, it still had no senior management, almost no employees, no contracts in place with railroads to provide any rail service, and no real indication of the long-term financial prospects of the routes selected. There was much to be done before May 1.

To be continued…

[1] Incorporators Meeting Summaries, National Railroad Passenger Corporation, December 22, 1970 – March 30, 1971. From the papers of Frank Besson, Jr., Box 53, in the Special Collections division of the National Defense University Library, Washington, D.C.

[2] Jim McClellan. My Life in Trains: Memoir of A Railroader. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2017 pp. 192-193.

[3] U.S. Congress. Senate. Committee on Commerce. Nominations-1970. (Hearings, 91st Congress, 2nd Session, on December 3, 16, and 29, 1970). Washington: GPO, 1971 pp. 36-37.

[4] McKinsey & Company. Organizing the National Railroad Passenger Corporation: Initial Organization Charts, Job Descriptions, and Supporting Comments. December 29, 1970, p. 2. From the papers of Frank Besson, Jr., Box 45, in the Special Collections division of the National Defense University Library, Washington, D.C.

[5] Ibid p.5.

[6] Ibid p. 4.

[7] McClellan p. 192.

[8] McKinsey & Company. Preliminary Route Recommendations: National Railroad Passenger Corporation. March 2, 1971, pp. 1-2. From the papers of Frank Besson, Jr., Box 40, in the Special Collections division of the National Defense University Library, Washington, D.C.

[9] Memorandum to all NRPC incorporators, dated March 18, 1971, subject “Congressional Phone Calls, Friday, March 19, 1971” p. 2. From the papers of Frank Besson, Jr., Box 46, in the Special Collections division of the National Defense University Library, Washington, D.C.

[10] Statement of David W. Kendall, Chairman of the National Railroad Passenger Corporation, at a Press Conference in Washington, D.C., Monday, March 22, 1971 p. 2.

[11] Ibid p. 3.