February 14, 2018

Much of the attention to automated vehicle (AV) policies has often focused on the federal and state levels. But as companies begin to conduct more pilots of their AV technology in cities across the country, local leaders have started to consider how they might adapt their policies to prepare for AVs.

Up to this point, most AV testing has been conducted in Michigan and major cities on both coasts. In California alone, 50 different companies have registered with the state’s Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV). On the other side of the country, Uber has been testing its self-driving vehicles in Pittsburgh for well over a year, and limited testing is underway in Boston by Aptiv (formerly Delphi) and Optimus Ride.

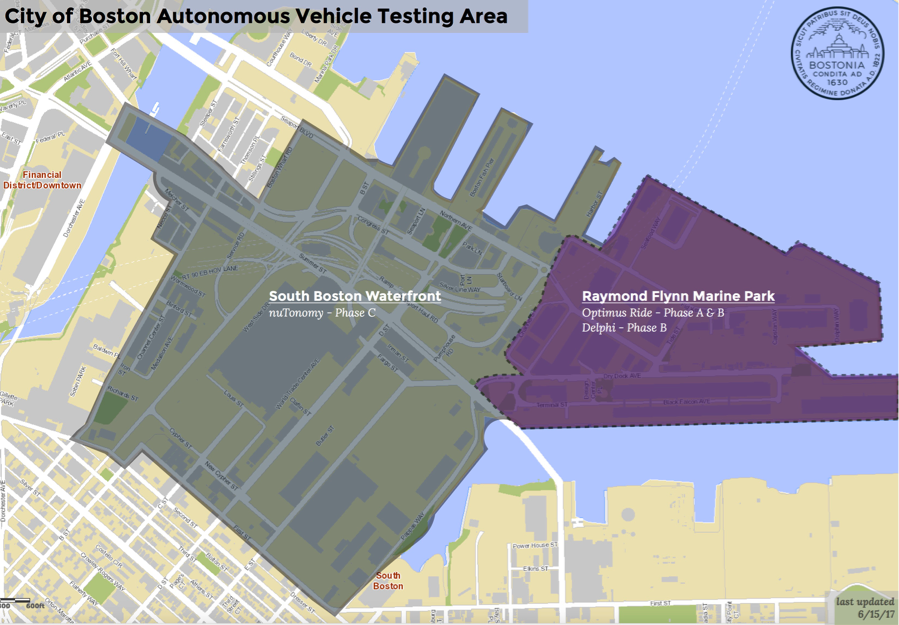

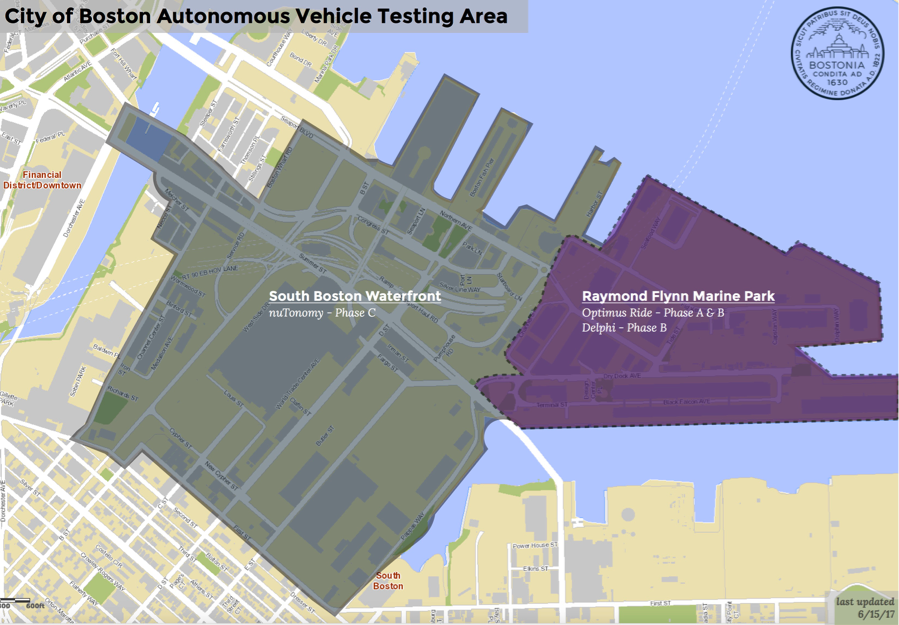

The City of Boston has taken an especially active role in overseeing AV tests in its jurisdiction. In October 2016, Mayor Martin Walsh issued an executive order to establish an AV policy framework for the city that emphasized a strong relationship between the city and manufacturers. This opened the door to testing by nuTonomy, an MIT spinoff that has since been acquired by Aptiv, and other interested AV manufacturers.

Boston AV Testing Zones, prior to Aptiv’s acquisition of nuTonomy (Source: City of Boston)

This policy framework has allowed Boston to play an active role in how and where AVs are tested, but is far from being the sole reason that AV developers are present in the city.

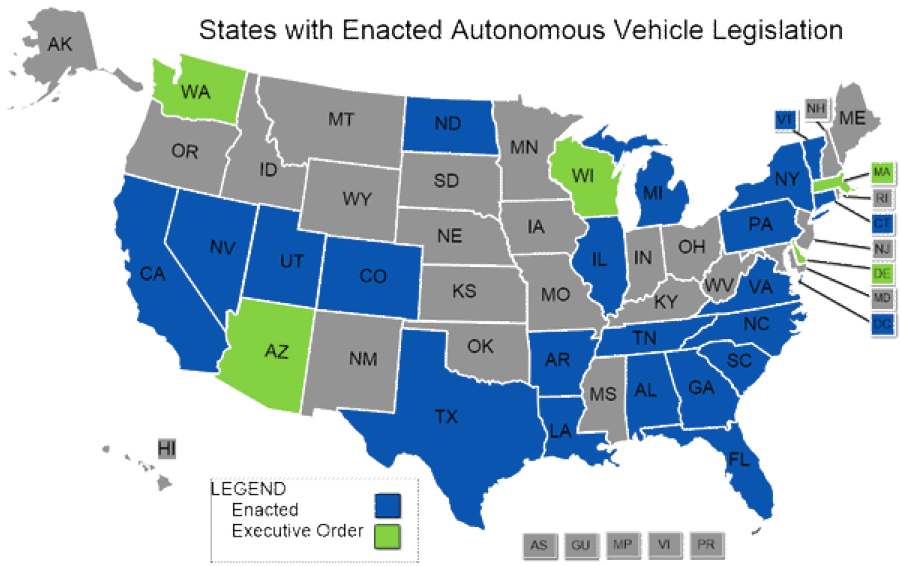

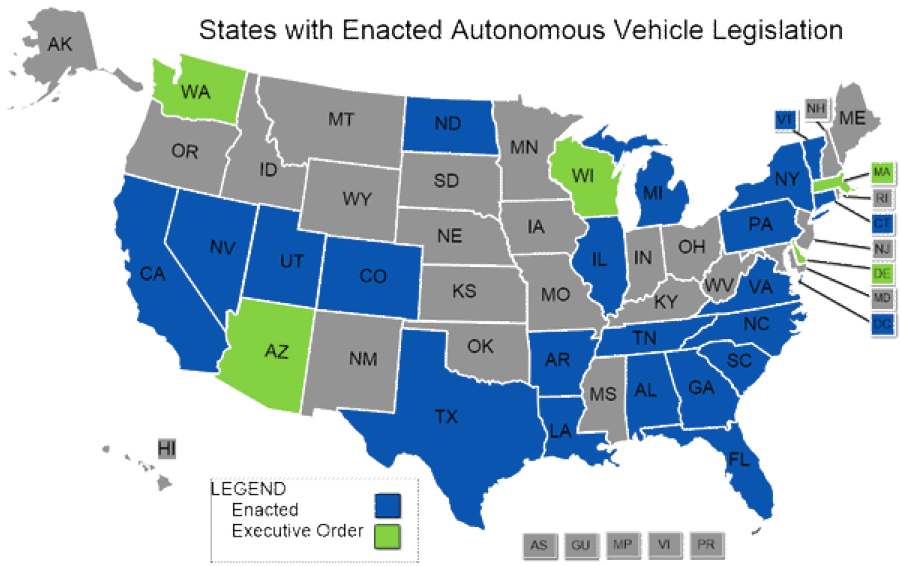

As Eno concluded in a 2016 report, Adopting and Adapting, establishing AV policies will not necessarily attract manufacturers to a state. In fact, 21 states and Washington D.C. have passed AV legislation, and governors in 6 states have issued executive orders pertaining to AVs, but testing is only occurring in a handful of those states.

The same lesson applies to cities.

(Source: NCSL)

Typically, AV manufacturers begin testing near where they are headquartered. But when they decide to expand their operations, they tend to look at a wide range of factors that contribute to successful testing and development, chief among them:

- Skilled workforce

- Temperate climate (although AV developers who are further along have began testing in severe winter weather)

- Local universities

- Well-maintained roads

- Permissive AV policies

- Various driving environments

Nevertheless, cities that are interested in AVs have a number of tools at their disposal to begin communicating with manufacturers and, when the time comes, ensure that AVs are used in a way that meets their specific goals for mobility, safety, and efficient use of their roadways.

The following is a set of steps that some cities have already taken to prepare for AVs in their jurisdictions.

- Form a Working Group

The successful implementation of AVs will require collaboration between a wide range of stakeholders including elected officials, state and local agencies, and industry. For this reason, some cities have started to form AV working groups to begin a dialogue around their community goals for AV implementation and also to identify potential policy barriers.

Case Studies: Beverly Hills, CA and Tulsa, OK

In April 2016, Beverly Hills, California was the first city to pass a resolution to create an AV program. As part of the initiative, Mayor John Mirisch signaled an intention to launch an autonomous shuttle system that would provide first/last-mile connections to the Purple Line extension of the L.A. Metro upon its completion in 2026. This led to the creation of an autonomous vehicle committee that works with policymakers, industry, and the broader community to explore future opportunities to bring AVs to the city and plan for the future widespread deployment of the technology.

And the City of Tulsa, Oklahoma recently formed a Urban Mobility Innovation Team in order to form an action plan for integrating emerging transportation technologies. This group is split into two teams: a policy team, which is focused on reducing the barriers to implementing AVs, and a technical team, which is identifying the infrastructure needs for AVs.

- Publish a Statement of Principles

Developing a statements of principles allows a city to publicly their residents, stakeholders, and AV developers:

- Why they are interested in AVs (e.g., safety, mobility, efficiency)

- How they will work with the public, stakeholders, and industry

- What type of AV pilot programs they are interested in (small driverless shuttles, self-driving Uber/Lyft/Waymo, etc.)

The most important piece of the puzzle is why. Every city has a unique set of transportation plans and objectives that reflect the specific challenges faced by their communities – and these cannot be solved with the snap of a finger and AVs suddenly appearing on their streets. By publishing a set of principles, rather than a stringent set of requirements for testing, cities can initiate a dialogue with developers – ultimately providing flexible guidance rather than prescriptive barriers to entry.

Case Study: Pittsburgh, PA

Setting expectations ahead of time helps to reduce friction between local policymakers and AV developers, as was the case for Uber and the City of Pittsburgh.

In September 2016, Uber launched the nation’s first AV transportation service in Pittsburgh. Initially, Pittsburgh Mayor William Peduto welcomed Uber with open arms – the company launched a partnership with Carnegie-Mellon University, established an Advanced Technologies Center in the city (which later poached scores of robotics experts from CMU), invested “hundreds of millions of dollars” in the city, and created hundreds of jobs.

“You can either put up red tape or roll out the red carpet. If you want to be a 21st-century laboratory for technology, you put out the carpet,” Peduto said to the New York Times that September.

But the relationship quickly soured as Peduto came to believe that Uber was not doing its part for the city after it had opened its doors to their AVs. This was exacerbated when Uber reportedly declined to participate in Pittsburgh’s USDOT Smart City Challenge application – which would have involved Uber’s AVs.

Then came the public backlash after some Pittsburgh residents were surprised to learn that AVs were operating on their streets – the result of inadequate public outreach. Making matters worse, photos and videos surfaced that showed an Uber AV driving the wrong way on a one-way street, and another that had allegedly pulled over after a collision.

In an effort to make this a learning experience (and likely with an added bonus of rebuilding public confidence before the November 2017 mayoral election), Peduto and the City of Pittsburgh partnered with the American Architectural Foundation (AAF) to hold the 2017 National Summit on Design and Urban Mobility.

The summit culminated in a comprehensive guide for cities to integrate emerging technologies in mobility through public-private collaborations. This included recommended principles like proactively managing change to ensure equitable outcomes, values like promoting safety for everyone – especially the most vulnerable populations, and action items like working with private sector partners to develop coordinated strategies for project planning and implementation.

In an interview with CityLab published on February 8 of this year, Peduto reflected on how the city’s relationship with Uber has evolved. (Note: A number of automakers are also testing AVs in Pittsburgh, including: Ford with Argo AI, BMW and Aptiv, and Carnegie Mellon with GM)

“I would say that they are learning,” he said. “There is a completely different culture between Ford—which has been around for 100 years, which stands in partnership with its workers and unions, understands workers’ rights, and is from Detroit—and Uber, which has a Silicon Valley background. It’s going to be in places like Pittsburgh and Cleveland and Detroit where Silicon Valley learns the lessons that we had to learn the hard way for 100 years.”

Case Study: Portland, OR

“Portland can show how to “do AV smart” by working with transportation providers and the public to implement testing and piloting of this technology, while advancing public safety, protection of the environment and transportation access for everyone, regardless of income.”

-Mayor Ted Wheeler and Dan Saltzman, Commissioner-in-Charge of Transportation

Portland has not yet experienced the same influx of AVs as the California cities to its south. Nevertheless, the city’s leaders recognized a need to prepare for the advent of AVs.

Mayor Ted Wheeler and Dan Saltzman, the Portland Commissioner-in-Charge of Transportation, launched the Smart Autonomous Vehicle Initiative (SAVI) in the interest of identifying best practices for AV testing and realize the full range of potential benefits of AVs.

“Portland can show how to ‘do AV smart’ by working with transportation providers and the public to implement testing and piloting of this technology, while advancing public safety, protection of the environment and transportation access for everyone, regardless of income,” the SAVI webpage says.

Wheeler and Saltzman sent a letter to Leah Treat, the Director of the Portland Bureau of Transportation (PBOT), instructing PBOT to launch SAVI in April 2017. In it, Wheeler and Saltzman identified a set of specific priorities for SAVI, such as advancing the city’s Vision Zero goal of eliminating all traffic deaths and serious injuries by 2025 and prioritizing fleets of AVs that are electric and shared.

The letter further instructed PBOT to take four actions within 60 days to advance SAVI:

- Propose Interim Transportation System Plan policies “that ensure connected and autonomous vehicles will serve Portland’s safety, equity, climate change, and economic goals;”

- Publish a Request for Information (RFI) to invite AV testing that will serve the four goals listed above;

- Adopt an Interim Administrative Rule to provide a clear path to permit testing, piloting, or deployment of AVs in Portland;

- Develop public engagement, reporting and evaluation plans to ensure residents and local stakeholders “have opportunities to shape the ‘rules of the road’ for AVs in Portland.”

3. Best Practice: Create a Roadmap

Amid all of the excitement around AVs, there is a tendency to focus on the technology itself – and the benefits it might bring – rather than the specific ways they hope to implement it. Instead, it is helpful to develop a loose framework (a roadmap, if you will) for realizing the benefits of AVs.

This approach can be condensed into a simple phrase: “If you don’t have a plan, you’re already there.” AVs are being tested and rolled out across the U.S. – and failing to prepare will not prevent the technology from being deployed, but could

By creating this roadmap, cities and industry partners will have a specific set of actionable steps they can draw on in order to accomplish their goals for mobility, accessibility, energy consumption, and so on.

Case Study: Seattle, WA

In a manner similar to Portland’s SAVI, Seattle developed a set of principles for integrating AVs. Portland built on this further by publishing a comprehensive playbook that not only outlines a vision for AVs, but a playbook for integrating AVs in their mobility ecosystem.

Seattle’s New Mobility Playbook draws on the city’s specific goals to develop a set of five plays for adopting emerging technologies in transportation:

- Play 1: Ensure new mobility delivers a fair and just transportation system for all.

- Play 2: Enable safer, more active, and people-first uses of the public right of way.

- Play 3: Reorganize and retool SDOT to manage innovation and data.

- Play 4: Build new information and data infrastructure so new services can “plug-and-play.”

- Play 5: Anticipate, adapt to, and leverage innovative and disruptive transportation technologies.

Each play was complemented with specific strategies in the initial document, which have since been supplemented with four appendices, available here.