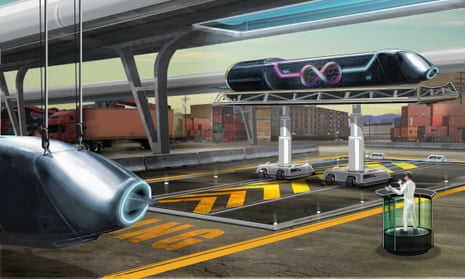

It’s like something out of the 1980s futuristic cartoon show The Jetsons: floating commuter pods are propelled through low-pressure tubes at 760mph, faster than an average 747 jetliner.

This is Hyperloop, a super-fast transportation system that promises to be better and cheaper than high-speed rail. The Hyperloop is the brainchild of Tesla CEO Elon Musk, who proposed the concept in a white paper back in 2013. Musk envisioned a train that would allow people to travel between Los Angeles and San Francisco – a journey that currently takes around six hours by car - in about 30 minutes.

Musk only introduced the idea; he’s leaving it up to other companies to try to develop it. An LA-based firm called Hyperloop One secured $80m in May to proceed to the next phase of its development, which includes testing on a patch of remote desert in northern Nevada. Meanwhile, competitor Hyperloop Transportation Technologies, which boasts engineers from NASA and Boeing on staff, announced it had licensed “passive magnetic levitation technology” to further its own Hyperloop vision.

Despite its success in raising funds, questions are being raised about the viability of Musk’s hyperloop concept. Some say the technical challenges will be too great to get the idea off the ground, while costs, including land acquisition, for rail projects can run into the billions.

The other issue is whether the system is actually fit to transport people. “I’m not sure that most of us have a strong enough stomach to ride inside a vehicle traveling at several hundred miles an hour,” says James Moore, director of the University of Southern California’s Transportation Engineering Program. “Whether such a system can provide a comfortable, humanly bearable ride is completely unclear.”

Musk’s elaborate vision may have attracted plenty of media attention and Silicon Valley funding, but it also highlights society’s tendency to get caught up with new transportation technologies, instead of the less exciting but perhaps more workable solutions - some of which may already exist.

“There’s always been an element out there that valued the ‘gee whiz’ factor rather than the economics,” says Moore. “But if you look closely at the cost, benefits and risks, new technologies frequently do not compete well, yet we continue to pretend it’s obvious we should adopt them.”

It’s generally easier to improve transport systems incrementally, says Moore. Yet recent history has produced some high concept ideas that have captivated imaginations but failed to really take off in the real world.

Take, for instance, personal rapid transit, a mode of public transport made up of driverless passenger podcars that travel on elevated tracks. It’s meant to marry the privacy of a car with the efficiency of mass transit. Although the idea has been around since the 1950s, only five systems have successfully been implemented worldwide, according to a 2014 study from think tank Mineta Transportation Institute.

Just one exists in the US, in Morgantown at West Virginia University, which launched in 1975. The other four - at Heathrow Airport in London, Rotterdam in The Netherlands, Masdar City in Abu Dhabi and Suncheon Bay in South Korea - all opened within the last decade or so, but that’s still “not enough to claim that there is an active market sufficient to support an industry,” wrote the authors of the report.

A big barrier is the cost to implement such a project. The study estimates that cities would need to cough up between $10m and $20m per mile to put in place a medium capacity system, and there are also only a few “credible” companies, says the report, who can deliver a personal rapid transit project within a couple of years.

It is this type of flashy futuristic idea that requires millions of dollars and huge new infrastructure that we should be wary of, says Robert Puentes, director of the Eno Center for Transportation, a Washington DC-based think tank.

“The focus right now in the US should be on making sure the existing system is performing as well as it can, and that it’s as safe as it can be,” he says.

Focusing on individual investments distracts policy makers from the core issues they need to focus on, says Puentes. “What are we trying to accomplish?” he asked, “How are we going to get it done? How do we get the funding?”

Sharing economy and buses

There are major tech changes already taking place that are having a radical influence on how we move around. The internet and the sharing economy for example is seeing companies like Uber and Car2go fundamentally change how people travel, leading to a drop in private car ownership and an increase in public transit use. People are right to get excited by these developments and other ones that keep existing systems, ie our roads, running in a more efficient and cost effective way, says Puentes.

Expanding a city’s bus services isn’t exactly headline-grabbing, but it’s an example of the type of sensible transportation initiatives that should be getting more attention, he says. For instance, the city of Houston, in Texas, recently improved its decades-old bus system simply by adding more hours and additional days to several key bus lines.

The goal was to make better use of the city’s existing fleet of 1,200 buses without raising operating costs. The initiative, launched in August 2015, cost just $10m of an annual $300m budget. So far, the project seems to be working. Weekly bus and rail ridership went up by nearly 10% in the months following the increased service.

“They focused around the redesign of old technology, and it has fundamentally changed how people in the city travel, and it’s been very well received,” says Puentes.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion